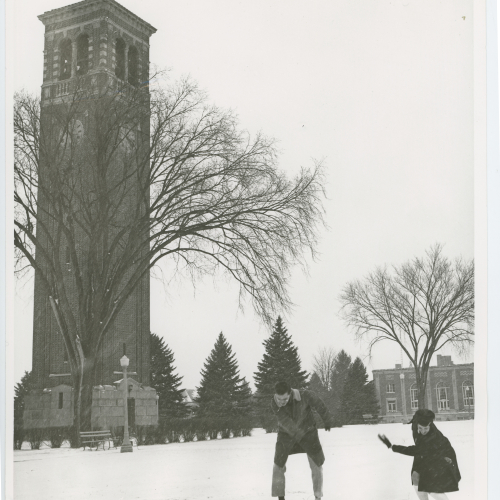

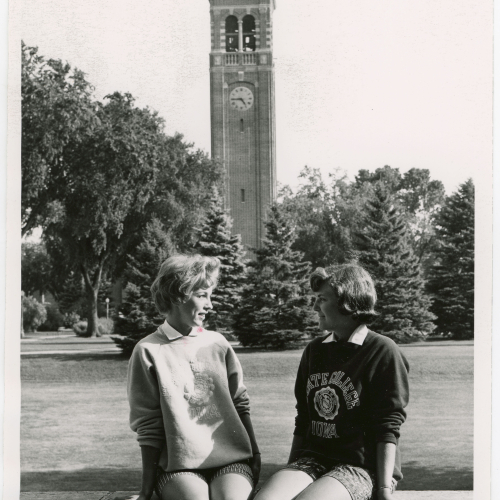

Campanile (1924)

“The Campanile is a metaphor for UNI and what we are all about. The University of Northern Iowa provides a very solid foundation through the education students receive here that allows our graduates to chase their dreams, to reach for the sky and create a life that enhances the lives of the people around them. The solid granite base of the Campanile is much like the education one receives at UNI. It provides the solid foundation upon which the Campanile reaches into the sky and counts the passing of time, and the Carillon provides the music that enhances the lives of everyone around campus.” - UNI President Mark Nook, 2018

The tradition of campaniles stretches over a thousand years. Usually, a campanile served as a bell tower for a nearby church. The root of the word campanile is the Late Latin campana, meaning bells. The earliest campaniles were cylindrical: the Leaning Tower of Pisa is a modified example of the round-base style. Later, campaniles tended to have square bases. Classic versions include the Campanile in St. Mark's Square in Venice and the Campanile di Santa Maria del Fiore, better known as Giotto's Campanile, in Florence.

Interest in building campaniles revived in the nineteenth century. Sometimes these later campaniles would still be associated with a church. However, campaniles were also built either freestanding or attached to commercial, industrial, government, and collegiate buildings. There are several campaniles in the Midwest: for example, the 1897 structure on the Iowa State University campus and the more recent 1988 Henningson Campanile on the University of Nebraska at Omaha campus.

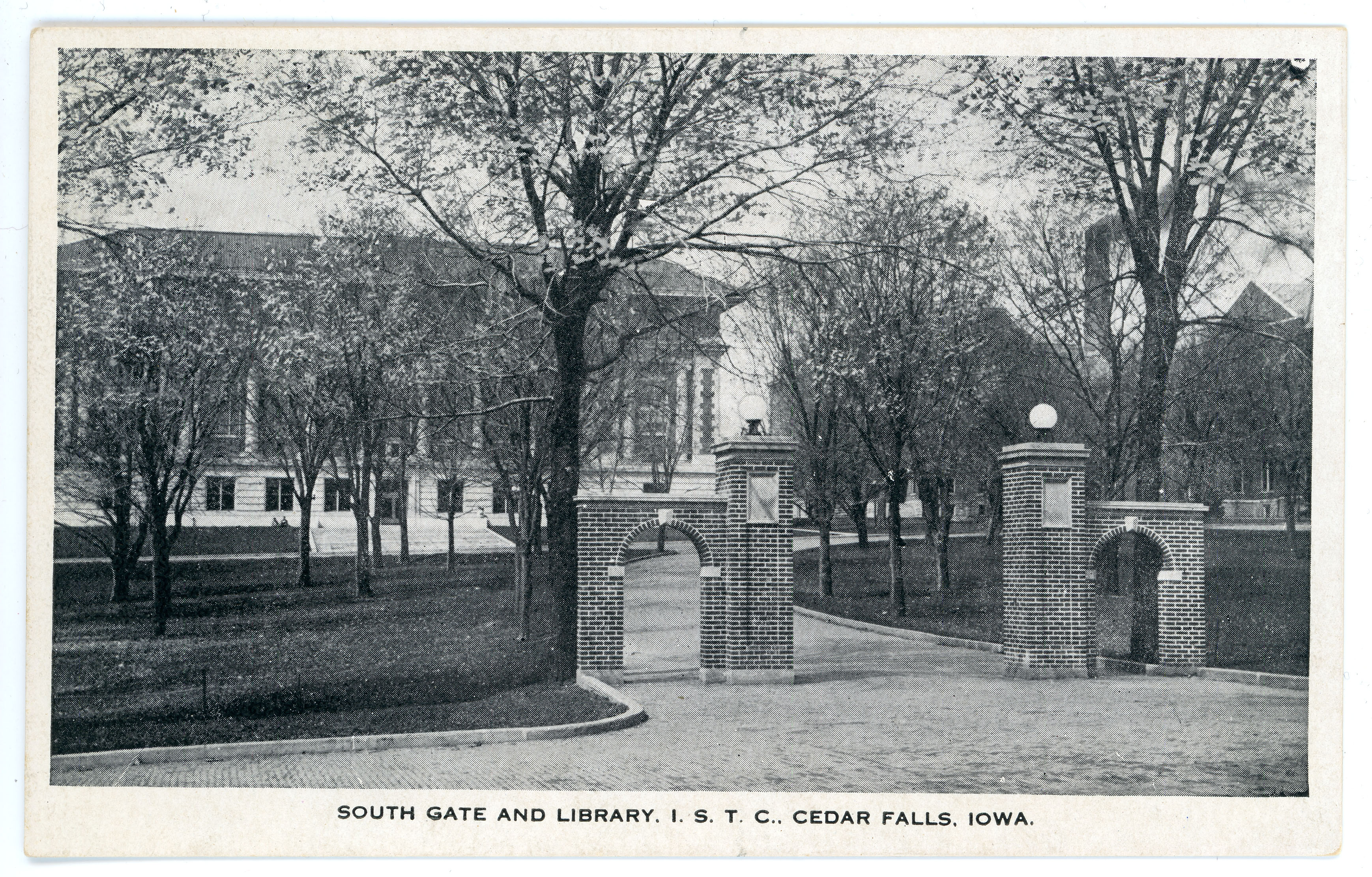

The UNI Campanile was ultimately the result of almost twelve years of planning and work. Over the course of the Iowa State Normal School's history, graduating classes often collected money to purchase small gifts for the institution. These gifts included such things as a fossil for the Museum, art reproductions, a plaque, or a set of chairs. The Classes of 1912, 1913, and 1914 raised the bar when they donated enough money to build decorative gateways along College Street.

When alumni came to campus for their annual meeting at Commencement in June 1914, Alumni Association President Fred Sage appointed a committee to "consider the matter of erecting a suitable memorial in behalf of the faculty, graduates, students, and friends of the institution." The committee, consisting of alumni Charles Meyerholz, Bruce Francis, Emma Lambert, Mrs. C. H. Wise and Charles A. Fullerton, studied the matter and a few months later recommended building a "grand and inspiring memorial in the form of a beautiful campanile." The base of the memorial would be twenty feet square; the tower would be one hundred feet tall with a large clock near the top. It would cost $12,000.

The idea of the memorial was officially presented to students on October 19, 1914, when professor Charles Meyerholz (1898), spoke to over a thousand students in the auditorium of what is now Lang Hall. Professors Ida Fesenbeck and David Sands Wright, former Board member Roger Leavitt, and alumna Emma Ridley Colegrove spoke strongly in favor of the project. President Homer Seerley echoed their thoughts and appealed to all students, former students, faculty, and even Training School pupils to consider giving at least something toward the memorial, so they all could feel they had been a part of the grand structure.

Despite initial enthusiasm for the project, matters were quiet until May 1915. The Class of 1915 pledged 1% of their salary for the coming year to the Campanile fund. While the class did not quite meet its goal, they did raise about $1,000, mostly in pledges. A year later, in May 1916, the College Eye student newspaper noted Meyerholz's report that contributions ranging from $5 to $100 were coming "in a very satisfactory way." The newspaper challenged the Class of 1916 to match or exceed the Class of 1915 in supporting the Campanile. The class decided to direct whatever funds it collected to the Campanile rather than to a smaller gift.

By the time the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Meyerholz reported about $5,000 had been pledged to the Campanile fund. There were no special attempts to raise money during the war. Following the war, the project took on a new meaning. At its inception, the Campanile was conceived as a memorial to the students, faculty, and founders of the school. In the wake of national sacrifice for the war, the climate for a memorial changed. Across the country, communities and organizations were planning buildings, memorials, parks, and other public expressions of gratitude to remember those who served.

The Iowa State Teachers College was no exception. A headline in the February 19, 1919, issue of the College Eye declared: “Campanile Proposed as Memorial to War Efforts; Every Alumnus, Student, Teacher, and Friend Should Rally to Support of College”.

The plans and price were still the same, but the motivating spirit had changed. The article solicited contributions, however small, from everyone who had ever had a connection with the school. It promised there would be careful accounting of all contributions and contribution records would be open to the public. Plans in spring 1919 indicated the memorial could be completed within two years.

In June 1919, the Alumni Association examined designs for the memorial, hoping to start construction in the fall. The committee, consisting of Charles Meyerholz, Charles A. Fullerton, Sara M. Riggs, Emma Lambert, Mrs. C. H. Wise, and Benjamin Boardman requested everyone make a donation to the project.

Cash donations were scarce. The Class of 1918 donated $15.80. Alumni contributed $1, $2, or $5, with total quarterly contributions sometimes under $50. Consequently, the Alumni Newsletter of April 1, 1920 appealed: "Remember that $1.00 and $2.00 subscriptions will never build the Campanile but that $10.00 and $20.00 subscriptions will build it." Designated faculty members would canvass their departments for contributions. The newsletter also presented a sketch of the proposed memorial.

The Student Council made a strong push for contributions that spring. The Philomathean Literary Society donated $25. A large student meeting resulted in 315 students pledging a total of $1,950, with more student pledge cards still to be turned in. In May 1920, about $10,000 had been pledged, and about $2,100 in pledges had actually been paid. By July, the total cash in the fund was about $2,800. By September, the total had grown to $3,000, and in April 1921, $3,200. That spring there was a campaign to raise additional money. A brief article in the College Eye stated the cost of the project had risen to $40,000, but only about $3,500 in cash had been collected.

Fundraising efforts were limited by the economic hardships of the early 1920s, and articles about the Campanile in campus publications were rare. By October 1923, there was still less than $5,000 in cash in the fund and construction costs continued to rise. Consequently, in 1924, the Alumni Association appointed a new Campanile Committee headed by Albert C. Fuller, associate director of the college Extension Service.

The new committee established clear goals and adopted the slogan: "A Campanile for I.S.T.C. in 1926." That year would be the 50th anniversary of the college and 40th anniversary of Homer Seerley’s presidency. Fuller announced a fundraising banquet for local alumni. Professor Alison Aitchison persuaded the Class of 1924 to donate all their surplus funds to the project. She, along with professor Harry Eells and secretary Benjamin Boardman, brought a model of the Campanile into the chapel and gave "peppy talks" to the assembled students.

The fund received pledges but little cash. College faculty were among the significant contributors. The cost of the project had now risen to about $50,000. The committee said it would proceed with construction when the cash level reached $10,000. In May 1926, the College Eye "Inquiring Reporter" asked students if they thought the Campanile money could be better spent on something else. One student thought the Campanile was "the bunk." Another thought the money would do more good in the Student Loan Fund than in an "expensive, ornamental, and useless building." However, others liked the Campanile and what it represented.

The pace of fundraising increased. In June 1924, the Alumni Association received estimates for the project: $20,000-$25,000 for brick and stone; $12,000 for the clock; and approximately $15,000 for a 13-15 bell chime. Assorted cash contributed to the project. A previous fund for student entertainment was dispersed, with half, $510, going to the Campanile and half to the student loan fund. The Spring Music Festival Committee had $1,000 ready to contribute when construction began. The Minnesingers Glee Club presented a benefit performance for the Campanile to a full house in the Auditorium.

The college formed an Alumni Council to represent the project across the state. On September 30, 1924, Robert Fullerton, a noted tenor and former music faculty member, returned to campus to perform; also on the program was the new head of the Orchestral Music Department, Edward Kurtz, in his campus debut performance on violin. Proceeds from this performance, over $160, went to the Campanile fund. By mid-October 1924, the fund’s cash level was about $6,800 and pledges totaled $20,500.

The Campanile Committee were confident in this level of cash and pledges. They asked the Board of Education for permission to proceed with construction. The Board gave permission and appointed a committee from its own membership to work with the Campanile Committee to select a site, supervise construction, and manage finances.

The location of the Campanile was initially proposed near College Street, between the President's House and the College Hospital - now known as the Honors Cottage. Subsequently, the school had acquired forty acres of land on the western edge of campus and extending to Hudson Road. The group chose a site close to the middle of the newly-expanded campus.

The groundbreaking ceremony took place November 18, 1924. According to the College Eye, the senior class, led by the College Band, marched from the Auditorium steps to the building site. Hundreds of students and many faculty members joined the group. Eliza (Rawstern) Sands Wright, a member of the first four-year graduating class of the Normal School in 1880, turned the first shovelful of soil. They sang the ISTC Loyalty Song and committee head A. C. Fuller spoke.

As of the groundbreaking, the Board of Education had accepted the project and the State Architect. However, only about half of the $50,000 for the project had been raised or pledged. In December 1924, the committee announced a special radio broadcast over WSUI on February 17, 1925. Alumni groups were urged to arrange banquets and reunions for ISTC alumni at convenient locations around and outside Iowa at the time of the broadcast. The program would originate in the Auditorium, where the Minnesingers would sing and President Seerley and others would talk about the Teachers College.

The broadcast went well. People in over twenty states, as well as Canada, reported hearing the broadcast. The cash total for the Campanile fund rose from approximately $8,000 to $14,000 in a few months.

A month after the broadcast, the college was gifted a clock mechanism for the Campanile. Earlier, committee head Fuller had learned a famous clock mechanism would be given to "the institution or municipality that could afford it the best setting." Known as the Fasoldt Clock after inventor Charles Fasoldt, it had won a prize at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.

After the Exposition, the Fasoldt Clock Company continued to exhibit the mechanism. In 1925, the company decided to give the clock away. Fuller brought the matter to President Seerley’s attention. They decided to ask Teachers College alumnus and former faculty member James Owen Perrine, who lived in the East, to go to Albany to inquire about the clock. Twenty years later Perrine recalled his visit:

"When I arrived in Albany at that time, Mr. Fasoldt had a pile of telegrams on his desk several inches high, due to the fact that his offer had been put on the Associated Press wire. He didn't know what to do and he had no basis or background for selecting any of those who asked for the clock. I had taken along a photograph of Mr. Seerley and a copy of the College Annual, and in an hour or so had sold Mr. Fasoldt the idea of giving the clock to Cedar Falls… Furthermore, I presented the idea that the setting for the clock in the Campanile at Cedar Falls would be one which would receive special attention from all the good folk of Northern Iowa. Moreover Mr. Fasoldt, as the result of my personal solicitation, visualized perfectly and intimately the real appreciation that Iowa State Teachers College would have for his [grand]father's clock. In other words, I confidently believe that young Mr. Fasoldt would not ever have considered giving the clock to Iowa State Teachers College had I not personally presented the case to him. The clock was sought for very diligently by New York University and other much better-known institutions than Iowa State Teachers College."

In March 1925, Fasoldt announced he would donate the clock to the college. Two years later, when the Campanile was complete, he presented the clock mechanism and installed it, along with a mechanism that struck the Westminster change on the quarter hours.

Thanks to this gift, the committee’s projected $10,000 cost for a clock could be redirected to other Campanile expenses. Later that spring, the total cost of the project was reported at $60,000. As school closed in May 1925, the College Eye reported students had pledged an additional $4,000 for the project.

The cornerstone of the Campanile was laid June 1, 1925, in association with Commencement. Fred C. Gilchrist, a son of the school's first president James Cleland Gilchrist, spoke at the Commencement breakfast. Following his address, the College Band led a procession to the building site. Professor David Sands Wright gave the invocation. President Seerley introduced Pauline Lewelling Devitt, a member of the Board of Education. Devitt was the daughter of Lorenzo D. Lewelling, head of the Normal School Board of Directors which hired Seerley in 1886. She and Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds James E. Robinson laid the cornerstone. Then Devitt gave an address paying special tribute to Seerley’s 40 years at the college, comparing him to Moses leading the Israelites through the wilderness.

The cornerstone rested on a base of reinforced concrete 24 feet square and 6 feet deep. This foundation would support a tower about 101 feet tall. The walls of the Campanile would range from 20 to 37 inches thick. The building materials were sourced from several midwestern sites: the granite base from Sauk Rapids, Minnesota; the brick from Rockford, Illinois; and the limestone from Bedford, Indiana. The brick would be laid in an English cross bond pattern. The inscription on the base of the structure, suggested by college alumnus and business manager Benjamin Boardman, would read: "In Memory of Founders and Builders of Iowa State Teachers College." The projected dedication date was May 31, 1926.

By late September 1925, the college was putting together a 50th anniversary celebration featuring the Campanile as well as a pageant, with "hundreds of characters in costume, orchestra, choruses, dancing, and unique lighting effects…" James Schell Hearst, later a member of the English faculty and a distinguished poet, wrote the pageant, “The Spirit of Fifty Years.” In January 1926, Boardman reported the cash fund had reached $17,000.

Fuller and the committee began to focus on the bells for the tower. He hoped to have sufficient funds to purchase a set of 15 bells ranging in size from 450 to 5,000 pounds. The bells would be played both by a manual console in the tower and by a remote electric keyboard. By February, the 15 bells were being cast by the Meneely Company of Watervliet, New York. The contract price for the bells was $22,500, including installation in the Campanile. Later sources indicate the total bill was about $25,000. While plans remained for a remote electrical keyboard, initially the bells would be played manually by a console in the tower. The College Eye published an illustration and detailed description of a console in March. Despite the relatively limited two octave range of the fifteen bells, college officials seemed assured most music could be played on this chime. By mid-May 1926, the bells were ready to be shipped to Cedar Falls.

By June 1926 the tower was about two-thirds complete with a projected completion date of August. By July, the clock faces were in place and work was progressing on the belfry. The belfry floor, a concrete slab 14 inches thick and weighing 15 tons, was completed by late July. The bells were placed on timbers at ground level for inspection. In mid-September 1926, the Meneely Company mounted the bells in the belfry. The bells themselves were mounted in stationary positions; only the clappers moved. The bells were tuned and dedicated as follows:

- Bell 1--C--President

- Bell 2--D--Founders

- Bell 3--E--Citizens of Cedar Falls

- Bell 4--F--Schoolchildren of Iowa

- Bell 5--F#--Faculty

- Bell 6--G--Students and Alumni

- Bell 7--A--Our Wartime Heroes

- Bell 8--A#--Fathers and Mothers of Iowa

- Bell 9--B--Teachers in the Common Schools

- Bell 10--C--State Board of Education

- Bell 11--C#--Musical Organizations

- Bell 12--D--Dramatic Art

- Bell 13--E--Literary Societies

- Bell 14--F--Christian Organizations

- Bell 15--G--Athletic Activities

When the clock struck the Westminster change on the quarter hours, the bells dedicated to the President, the Schoolchildren of Iowa, the Faculty, and Students and Alumni would ring.

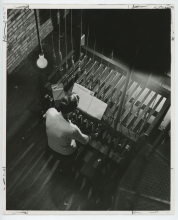

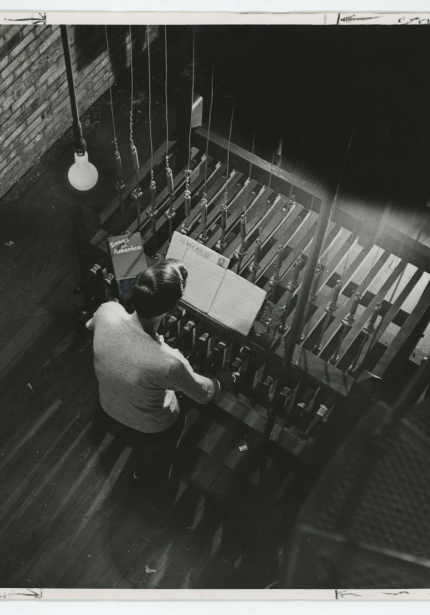

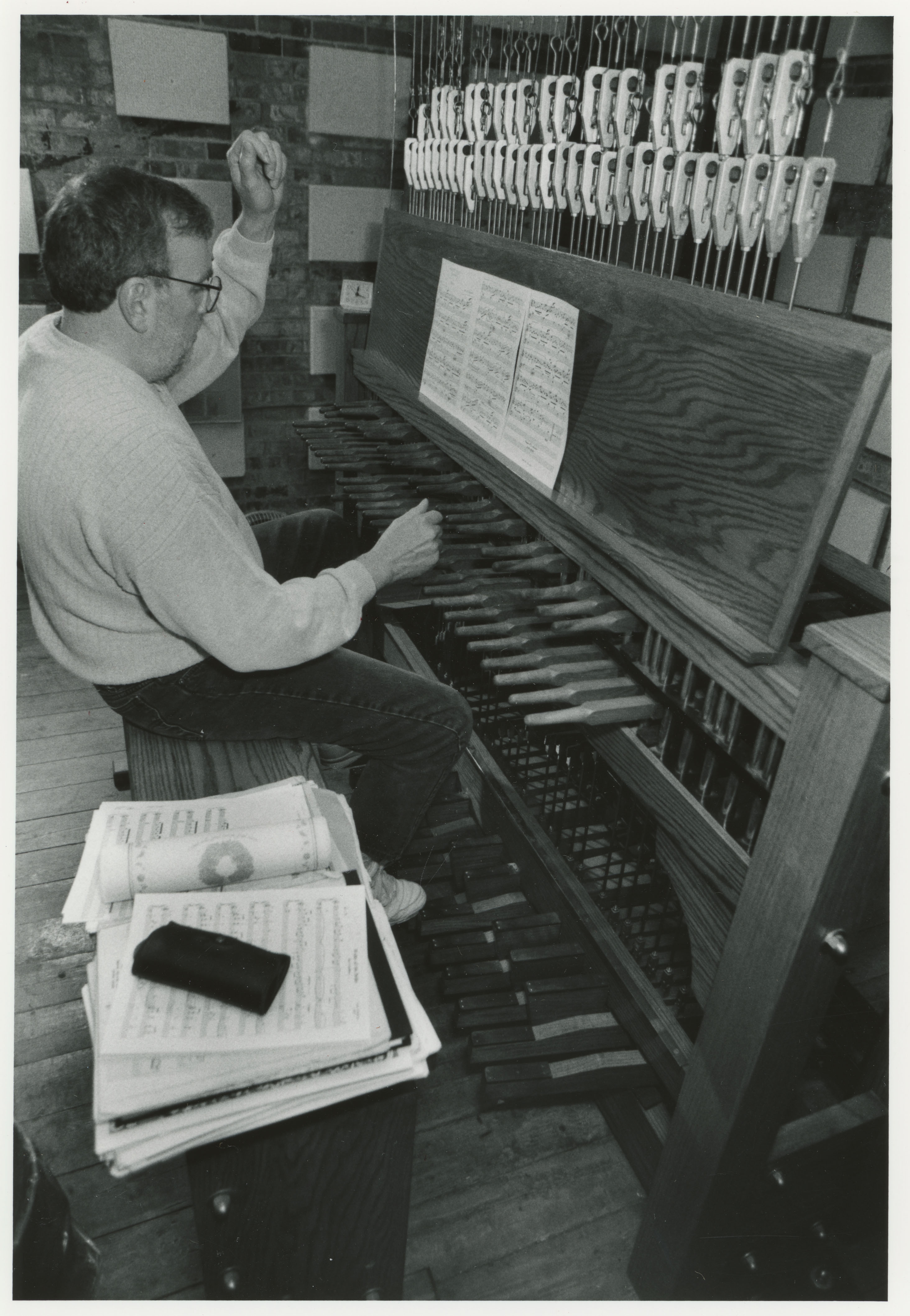

An installation program was scheduled for September 19, 1926. The College Eye reported 12,500 people attended the program. Andrew Meneely, from the company which manufactured and installed the bells, performed a long concert of religious, folk, and patriotic music. He performed half of the concert on the manual console inside the Campanile and the second half on an electrical keyboard in the College Electrician's office. The music from the bells could be heard for blocks around campus.

By this date, everything except the clock mechanism was in place. Most of the mechanism was shipped and arrived on campus in November 1926, but several parts were damaged during the process. Dudley Fasoldt made replacement parts and, in May 1927, drove from New York to Iowa with the most delicate pieces. The four clock faces on the Campanile are seven feet across, with bronze figures 15 inches high, and the original wooden clock hands were three and a half feet long.

On Armistice Day, November 11, 1926, just weeks after the structure was dedicated, the Cedar Falls American Legion Post presented a bronze tablet commemorating the eight ISTC men killed in World War I: Clifford Stevens, Charles Wesley Chapman, Jr., Henry Booth, Ernest Hansen, A. E. Justesen, Walter D. Koester, Dwight L. Strayer, and Einar Nielsen. It was placed in the Campanile. Several years later at the time of his retirement, a bronze medallion of President Seerley was added to "The Memorial Room" of the structure.

In February 1927, President Seerley and the Campanile committee sent "artistic reproductions" of the Campanile in winter to members of the Board of Education. The 1930 Teachers College exhibit at the Iowa State Fair included a painting of the Campanile by Katherine Rose, class of 1930. It was becoming a recognizable campus landmark.

Shorty daily concerts were played on the chimes. Music faculty member Irving Willis Wolfe was the first campus chime master. He also trained students to play: Pauline Johnson and Edna Wolfe, Wolfe's sister, began performing in January 1927. Wolfe played on the manual console in the Campanile; the students played on the electric keyboard. Students generally played the brief daily selections and received $10 per month. Wolfe performed longer, more professional concerts, typically on Sundays. The repertoire included sacred, folk, and patriotic tunes.

Although construction was completed, debt remained on the Campanile’s cost. In July 1927, the committee reported it had spent $50,647.59. It had collected about $42,000 in cash and had about $4,000 in pledges still unpaid, and needed $8,000 more to be debt free. Interest on the debt accrued at the rate of about $5 per week. The debt was paid off by 1930.

Despite its impressive credentials, within a few years the Fasoldt clock mechanism began to have problems. In summer 1932, the Campanile roof was improved to repair storm damage and prevent moisture from getting down to the clock mechanism. The clock mechanism was now housed in a wood and glass case, and its area heated to reduce moisture which affected the clock’s accuracy. Fine screens were installed in the belfry to keep out birds. Electrical systems were updated to accommodate the shift from direct to alternating current in the campus electric supply. The Westminster change which rang on the quarter hour was modified to be struck entirely by electricity; this modification made it possible for quarter-hour changes to be switched off if a concert were in progress. Prior to this improvement, performers had to stop playing to allow the quarter-hour change to be struck. In spring 1933, the granite foundation blocks were tuckpointed to repair frost damage.

Unfortunately, the change to alternating current caused a major problem for the Campanile. The diminished voltage of alternating current did not provide enough power to the electric keyboard for the bells to be struck sharply. The sounds produced from the electric keyboard were slow, sonorous, and out of tune. Consequently, until better electrical equipment could be installed, all performances had to be played on the manual console. This was hard physical activity, which some compared to playing football. Student chimer Fred Feldman developed seven blisters on one hand in the course of his short daily performances in 1934.

In 1938, President Orval Latham had the Campanile wired for amplified sound. Football game announcements, concert recordings, and other material could be heard more easily across campus. By 1939, the Campanile, the tallest structure on campus, began serving another purpose. A red light was mounted on its top as a signal to the night watchman. When someone at the Power Plant, which was staffed at all times, switched on the light, the watchman would find a telephone, call the Power Plant, and learn what the problem was. In 1941, the chiming mechanism underwent repair. The following summer, masons repaired damage caused by lightning, which had struck the tower and loosened bricks from top to bottom.

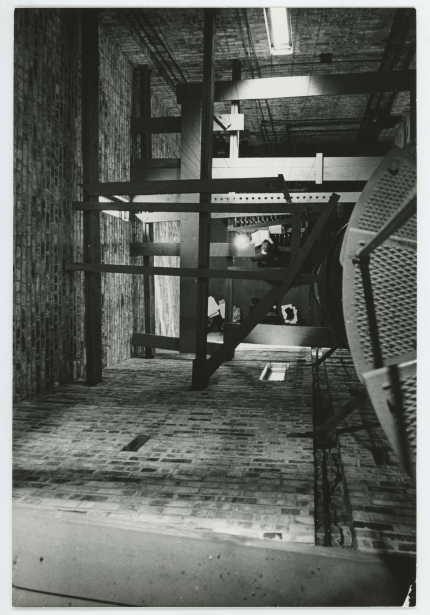

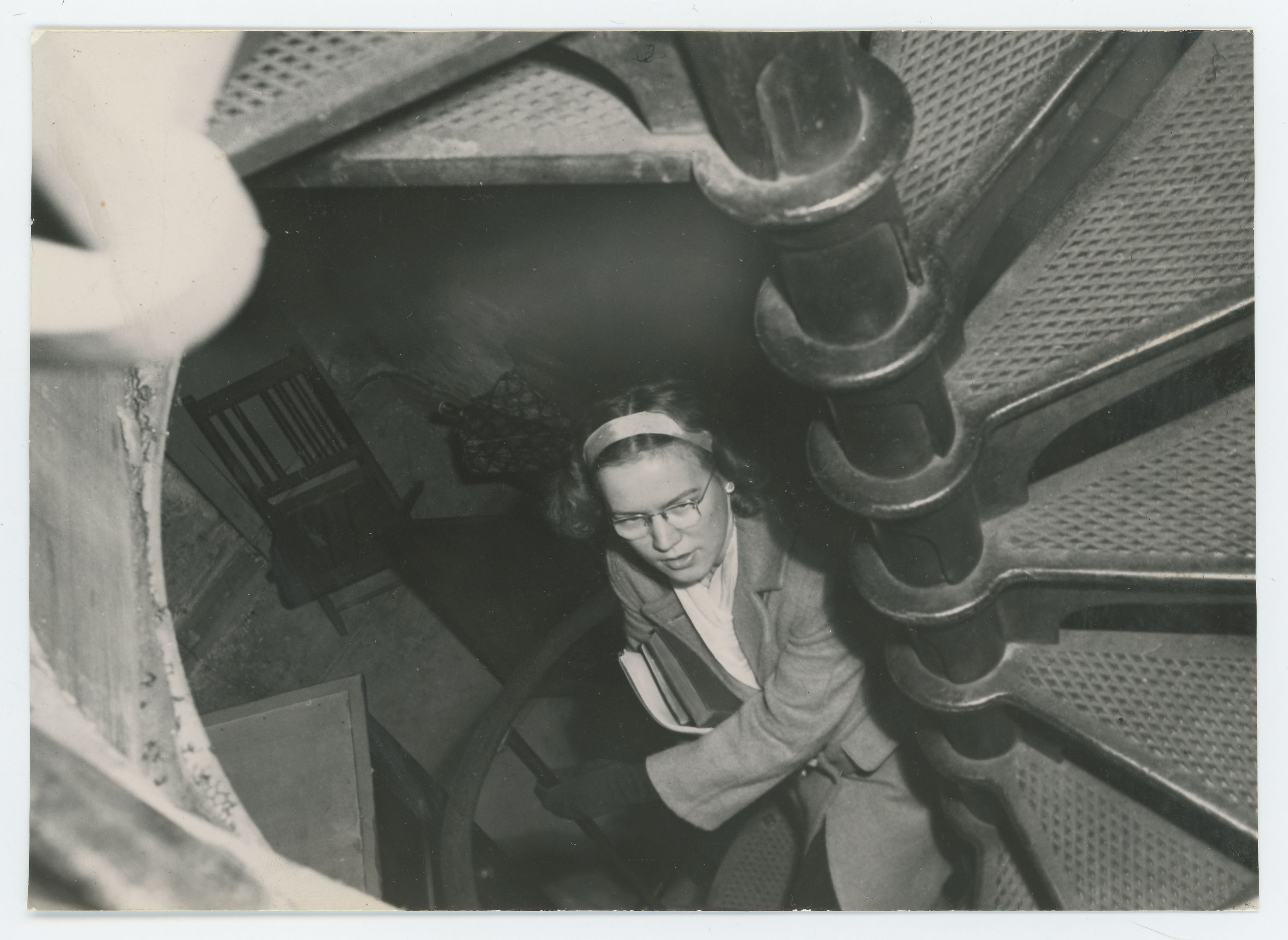

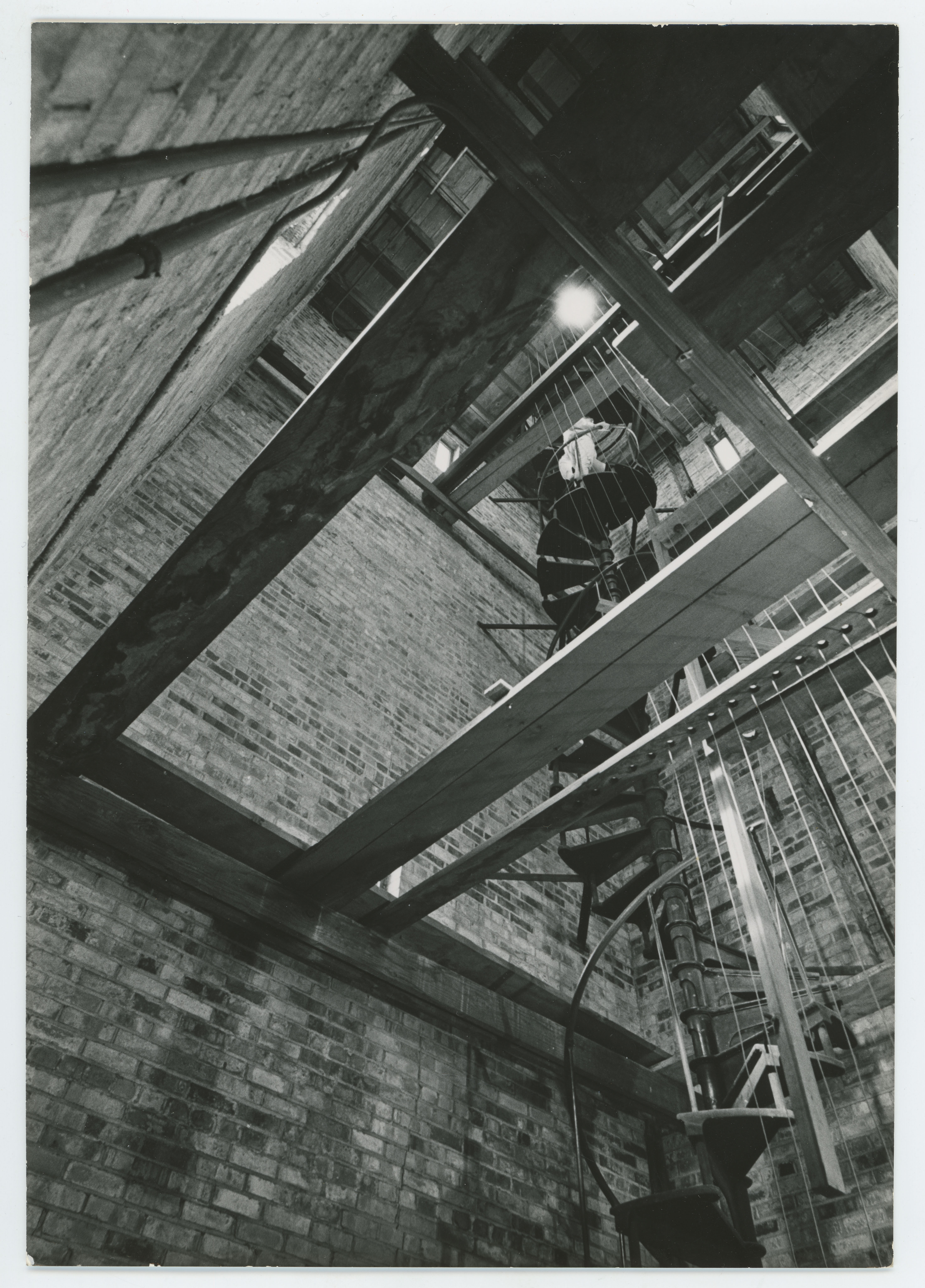

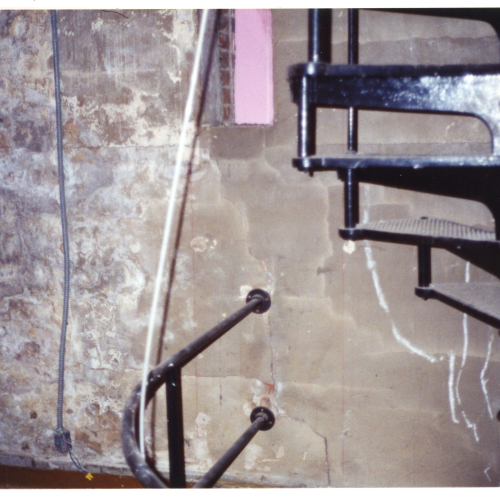

In 1942, a physical plant staff member offered tours of the tower. The ground floor held memorial displays. The next level included the Fasoldt clock mechanism and change ringing devices. Above that was the playing console. The levels were connected by a spiral staircase. In 1944, a part in the change ringing device burned out. Consequently, only three of the quarter hours rang until the appropriate copper wire, in short supply during World War II, could be replaced. All four quarters did not begin ringing again until 1949.

The Campanile clock’s accuracy differed from the campus clock system. This created issues when women had to keep “hours”: policy stated women had to be back in their dormitories by a specific time. Officials repeatedly warned students the campus electrical clock system was the "real" time; the clock in the Campanile was not. In 1946, college officials declared the Campanile clock was in "failing health" and began planning for a way to coordinate it with the campus clock system. In 1951, the clock received a new striking unit which would only chime on the hour, rather than each quarter hour. Finally, in 1953, the Campanile clock was connected to the campus system. Still, over the years, students continued to complain the time on the four clock faces did not match, or the hands on one clock face were stopped for weeks. In 1956, the steam pipes in the Campanile were re-fitted in another attempt to make the clock work better.

For 40 years, college officials maintained the bells in the Campanile, despite their relatively limited range of just under two octaves, did allow for a reasonable variety of music to be played. However, in 1965, professor Myron Russell, head of the Department of Music, wrote to the directors of the Alumni Association:

"For many years I have thought that an addition to our bell set would be one of the most worthwhile projects that the alumni could undertake. It is true that we do not need this to further our classroom educational program; however, for the over-all atmosphere of the campus and what it stands for, this addition would be most desirable. The present set of bells permits the player to play in only certain keys, and even some melodies that are written in what appears to be a playable key include a transient modulation which our bells often do not cover. Also, the number of our bells and the mechanical principle used in playing, permits the playing of only two part music when most of the time full four-part harmony would be highly desirable."

The directors of the Alumni Association agreed with Russell. They brought in a representative of the I. T. Verdin Company to conduct a demonstration using a portable four-octave carillon and were impressed by the possibilities this wider range offered. Consequently, they recommended the State College of Iowa (SCI) Foundation consider the purchase of additional bells if they could meet the following conditions:

- the existing bells could be integrated into the range of the new bells

- the Campanile could physically accommodate the new bells

- the Foundation could afford it

The initial projected cost was about $25,000 for an additional 32 bells.

Plans for fundraising were quickly underway. The Alumni Association intended to solicit graduating classes back to 1926. The Class of 1966 made plans to raise about $1,000 to purchase one bell as its class gift. A College Eye editorial writer wondered if this was the best use of Foundation funds, urging students to "vote" by contributing or not contributing to the project. Other students said additional bells would only mean more noise at times they were trying to sleep. This recurrent complaint largely disappeared once the university ceased using Baker Hall as a dormitory in 1970.

The Foundation asked the Alumni Association to inform alumni about the project and cost. Alumni could express their interest by making pledges, and if there were sufficient pledges by December 1967, the Foundation would back the project. An article in the Alumnus outlined potential costs:

- 32 additional bells--$8,385

- Steel framing for re-mounting all bells--$4,950

- Keyboard console--$1,400

- Linkage connectors--$4,950

- Clappers--$1,650

- Installation--$3,000

- Practice keyboard--$275

- Total--$27,085

The Alumnus article made a strong pitch for the new bells and controlling mechanisms. It also included a letter of support from President J. W. Maucker, in which he acknowledged re-fitting the Campanile was not as urgent as raising faculty salaries, increasing student aid, or building new facilities. Still, he argued, "the college needs symbols and traditions and aesthetic elements which are not of immediate practicality but which have an influence over a long period of time on many generations of students."

By May 1966, students had pledged about $900 and alumni had pledged about $3,000 to the project. The Foundation took confidence from this total and endorsed adding bells and re-fitting some of the playing mechanisms in the Campanile.

A "telefund" drive concentrated on three cities: a group headed by Robert Beach (’51) and Berdena (Nelson) Beach (’51) contacted Cedar Falls alumni; another group headed by Perry Grier (’38) and Mary Frances (Williams) Grier (’38) contacted Waterloo alumni; and a third group headed by Gene Lybbert (’52) contacted Des Moines alumni. They raised approximately $2,600.

By February 1967, the Alumni Association reported about 18% of the project’s $32,000 goal had been raised. By May 1967, the drive had reached the half-way point. Officials hoped to confirm contracts by December and finish work by Commencement in June 1968. In December 1967, with over $30,000 in the fund, President of the UNI Foundation Walter Brown signed a contract with the I.T. Verdin Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, for new bells and associated work. Petit and Fritsen Bell Foundry in the Netherlands would cast the bells and ship them around April 1968. Classes which met a $1,000 fundraising goal would have their year inscribed on a bell. Over five thousand people contributed to the project, which eventually raised about $34,500.

According to the February 1968 Alumnus, 35 bells were purchased: 32 new bells plus three bells to replace those out-of-tune. The net number of bells would make a 47 bell carillon. In preparation for the new bells and installation of a new console, the existing bells and clock were stopped in April 1968. By July 1968, the new bells, steel frames, console and striking mechanisms had been installed. The UNI Foundation declared:

“The 47-bell carillon will serve as a symbol of recent progress at UNI. It will reaffirm our thanks to the 'Founders and Builders' of UNI memorialized by the Campanile; and it will proclaim our loyalty to the University of Northern Iowa to generation after generation of future Alumni.”

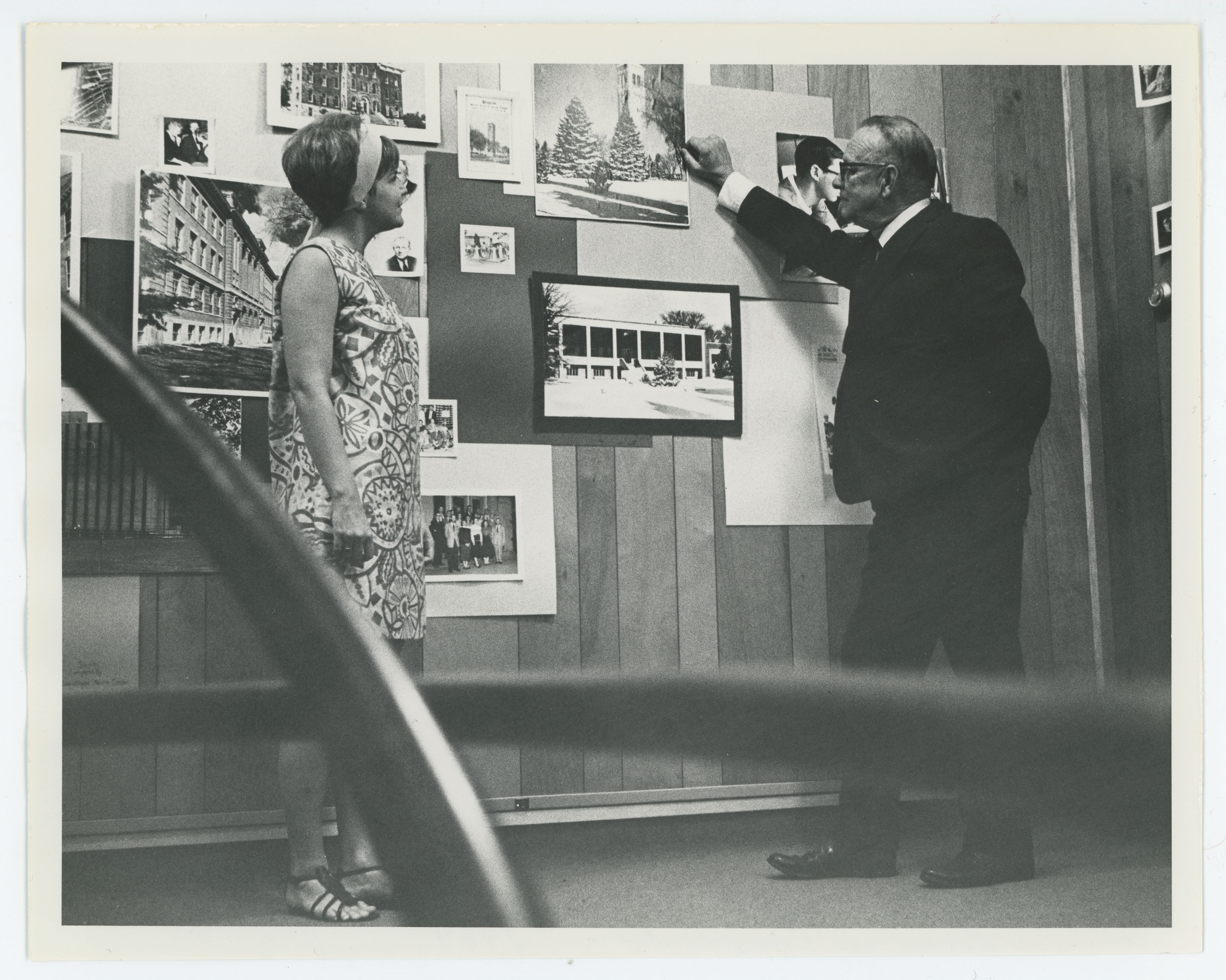

Other parts of the Campanile were also remodeled during this project. The ground floor became a reception room for alumni. It was paneled with wood from campus elm trees killed by Dutch Elm Disease. The next level became the memorial room. The playing console was moved upward to be closer to the carillon. The new carillon was dedicated during Homecoming in 1968. Wendell Wescott, carillonneur at Michigan State University, presented two concerts on October 19, 1968.

In 1967, carillonneur John Steffa began teaching Robert Byrnes, then a freshman, to play the carillon. Byrnes became the UNI carillonneur in 1972 and continued until his death in 2004. He was interviewed dozens of times by campus and local reporters about the peculiarity of performing on the instrument. In 1977, after two years of study with Richard von Grabow of Ames, Byrnes performed his master's degree recital on the Campanile carillon. Over the years, he performed in national and international carillon competitions. June 23-24, 1980, he hosted the meeting of the Congress of the Guild of Carillonneurs on campus.

Although Byrnes could make minor repairs on the carillon, by 1983 there was a list of serious repairs needing attention estimated at $50,000. Support for the project came from the Campanile Fund, the Chapel Fund, and the Student Building Fund. Work included a new console and adjustable bench, transmission system, clapper mountings and insulator pads between the bells and beams. Specifications went to six companies, and only the I. T. Verdin Company responded. They were awarded the contract and work was completed in November 1984. Afterward, Byrnes said, "Ours is now among the finest-playing carillons in the world."

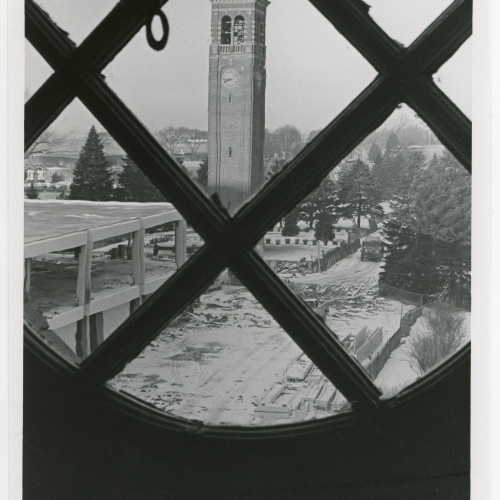

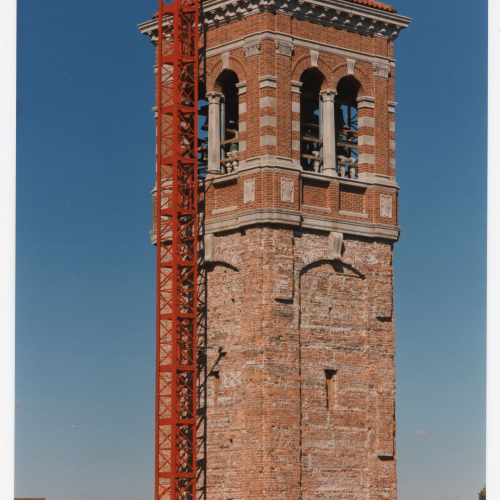

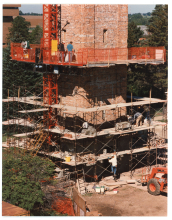

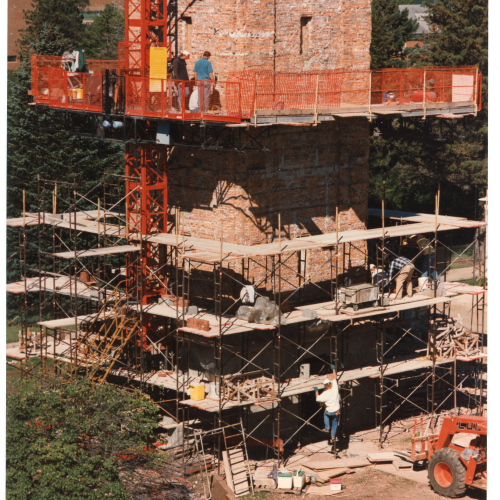

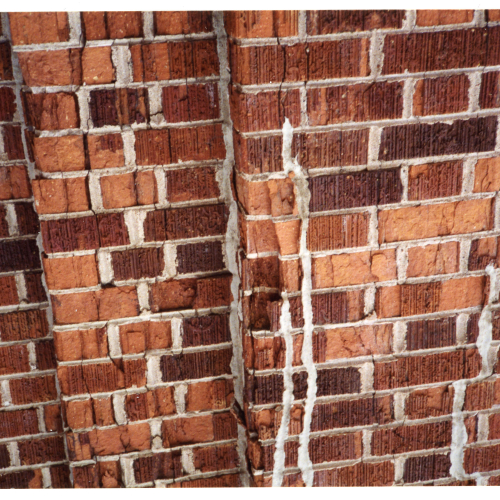

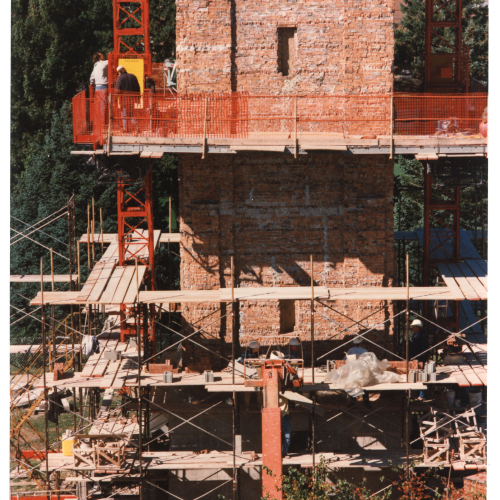

While the carillon was in good condition, the physical structure of the Campanile required updates. The Class of 1989 selected structural improvements to the Campanile as its class gift. Over the years, the masonry had cracked so the outer shell was no longer watertight, and some of the granite base blocks had shifted. The Class of 1989 hoped to raise $55,000 for this work.

In summer 1993, work began on a major renovation of the Campanile. Masons reset the granite base, removed and then relaid most of the exterior brickwork, and paved the area below the Campanile to create a plaza. Work was completed by late fall 1995.

Toward the end of December 1999, the clock motor quit working and the clock hands stopped. It took several months to receive a replacement motor, costing about $1,500. Physical Plant operations planner Paul Meyermann said, "The clock has been upgraded many times. The motor that went out is one of a kind."

After the death of carillonneur Byrnes on May 28, 2004, the carillon bells were silent. In November 2005, professor Kui-Im Lee and her organ students, Trevis Young, Jung-Min Lee, Mary McDonald and Kimberly Cordray, began to play the carillon. They learned and practiced together. Lee took lessons at Iowa State University from professor Tin-Shi Tam. Their informal performances continued through the spring 2006 semester and concluded with a series of open air concerts. Guest artist Karel Keldermans, carillonneur at the Rees Memorial Carillon in Springfield, Illinois, played for the traditional Homecoming campaniling at midnight on October 8, 2004. He also performed in concert the next day. Keldermans played again for Homecoming in 2005 and appeared on April 27, 2006, to perform a concert.

On September 18, 2006, the Campanile celebrated its 80th birthday. Keldermans again played the carillon. According to the article "Rejuvenating sound for Campanile is building's b-day present" from the Northern Iowan on September 15, 2006, the celebration marked the start of a campaign to solicit contributions for Campanile improvements.

By early 2007, the UNI Foundation was supporting a $300,000 project including $80,000 for a new D# bell, $50,000 for a practice keyboard, $60,000 to replace the actual playing keyboard, and $23,000 for hardware to connect the keyboard to the bells. Professor John Vallentine, director of the UNI School of Music, said, "It was really student government that started the main push. The students are behind this 110 percent, especially the older ones who heard the instrument when they were freshmen and sophomores." In an article in the Des Moines Register, Keldermans said, "At UNI, after I played, people came up to me and said it was good to have the carillon played again. It just becomes part of the musical and cultural fabric of the university."

Customs and Traditions

Several traditions are associated with the Campanile. An early tradition has it that because there were formerly so few men on campus, a male student would call a woman student at random and ask her to meet him at the Campanile at a particular time. He would then wait in the bushes. If he did not like her appearance, he would leave her waiting, go back to his room, and set up a similar date with someone else.

According to another tradition, a woman did not become a full-fledged co-ed until she had been kissed at midnight under the Campanile. The tradition seems to have begun shortly after the construction of the Campanile. It was brought back to life in 1979 by the Alumni Association. Couples gather under the Campanile on the Friday evening of Homecoming week. At the stroke of midnight, the couples exchange kisses.

Chimers, Carillonneurs, and Performances

Many faculty, students and staff have played the chimes and carillon throughout its history. The following were gathered from Campanile log books, student newspapers, other campus publications, and a 2022 spreadsheet from the UNI Guild of Carillonneurs. Due to gaps in records, it is only a partial list. Additionally, some dates are approximate. If a player and date are listed, there is documentary evidence they played at least during that time period. Some players performed long concerts on a regular basis, while others played shorter selections more sporadically. Visit https://carillon.uni.edu/ for more information about the UNI Guild of Carillonneurs.

- Chimers and Carillonneurs

- Fall 1926: Irving Wolfe and Luther Richman

- Spring 1927: Pauline Johnson

- Summer 1927: Frank Swain

- Fall 1927: Irving Wolfe

- Fall 1927 - Spring 1928: Doris L. Anderson and Norma Chase

- Summer 1928: Frank Swain, Edna Wolfe

- Fall 1928 - Summer 1929: Frank Swain and Gladys Arns

- Fall 1929: Harry M. Kauffman

- Fall 1929 - Summer 1931: Myrtle Kleist

- Fall 1929 - Fall 1933: Lois Roush

- Summer 1931: Gretchen Rausenberger

- Fall 1933 - Summer 1934: Ralph Moritz

- Spring 1934 - Winter 1935: Fred Feldman

- Winter 1935 - Summer 1936: Dorothy Oelrich

- Summer 1935 and Summer 1936: Lois Bragonier

- Summer 1935: Marjorie Palmquist and Fred Feldman

- Summer 1936: Harriet Todd

- Fall 1936: Fred Feldman and Ralph Moritz

- Fall 1936 - Spring 1938: James Dycus

- Summer 1938: J. Wesley Pritchard, C. Campbell, and Floyd Johnson

- Fall 1939: Doy Baker

- Spring 1939: James Dycus

- Summer 1940 - Spring 1941: Myron Messerschmitt

- Spring 1941: Warren Smith

- Summer 1941 - Spring 1942: William Jochumsen

- Fall 1942: Russell Calkins

- Winter 1942 - Spring 1943: Norman Paul Dearborn

- Spring 1943: Rupert Pipho, Joan Doon, and Lester Bundy

- Summer 1943: Russell Calkins and Owen Norman

- Fall 1943 - Spring 1945: Val Jeanne Fairlie

- Summer 1945 - Spring 1947: Lucile J. Craig

- Summer 1947 - 1951: Unknown

- 1951-1952: Don Jackson

- 1953: Frank Plambeck

- Summer 1953 - Spring 1955: Laurens Arthur Blankers

- 1955 - 1956: Curtis Noble

- 1956: Robert Wade

- Summer 1958 - 1960: Don Peterson

- Winter 1962 - 1963: Keith Haan

- 1964 - 1965: Leroy James LeFebvre

- 1966: Bruce Eilers

- 1968 - 1969: John Steffa

- 1969: Jerry Smithey and Robert Lodine

- 1971: Douglas D. Shaffer

- 1973 - 2004: Robert Byrnes

- 2005 - 2006: Kui-Im Lee, Trevis Young, Jung-Min Lee, Mary McDonald, and Kimberly Cordray

- 2007 - 2008: Kui-Im Lee and Danny White

- 2008 - 2010: William R. Beyer and Isaac Brockshus

- 2011 - 2012: William R. Beyer and Joyce Payer

- 2015 - 2016: Ben Owen, Rachel Storlie, Nicole Heinrichs, Alex Dunlay, Coren Hucke, Nick Behrends, Lydia Richards, Tommy Truelsen, Anna Larson, Dallas McDonough, Sam Oglive, and Owen Hoke

- 2016 - 2017: Alan Beving, Brenda Sevcik, Coren Hucke, Owen Hoke, Sam Oglive, Dallas McDonough, Anna Larson, Tommy Truelsen, Lydia Richards, Nick Behrends, and Loreena Hucke

- 2017 - 2018: Sam Oglive, Dallas McDonough, Anna Larson, Tommy Truelsen, Lydia Richards, Nick Behrends, Alan Beving, and Brenda Sevcik

- 2018 - 2019: Alan Beving, Brenda Sevcik, Tommy Truelsen, Lydia Richards, Nick Behrends, Adam Denner, Bethany Brooks, Joseph Tibbs, Abbie Greene, and Dakota Anderson

- 2019 - 2020: Brenda Sevcik, Joseph Tibbs, Abbie Greene, Dakota Anderson, Breeana De Vos, Rebekah Ostermann, and Greg Novey

- 2020 - 2021: Rebekah Ostermann, Greg Novey, Brad Lorence, Kayla Niessen, Ben Thessen, Tristen Perrault, Karissa Jensen, and Emily Clouser

- 2021 - 2022: Rebekah Osterman, Greg Novey, Ben Thessen, Tristen Perrault, Karissa Jensen, Emily Clouser, Jessica Carlson, Thomas Gumpper, Ryan Gruman, and Aiden Shorey

This list highlights a selection of Campanile performances.

- Highlighted Performances

- September 19, 1926: first concert on Campanile chimes, given by Andrew Meneeley, president of the Meneeley Bell Company at the Campanile Dedication Ceremony.

- October 19, 1968: concert by Wendell Wescott, Carillonneur at Michigan State University, to dedicate the renovations and additions to the set of bells.

- November 26, 1968: impromptu concert by Milford Myhre, Carillonneur of Bok Singing Tower at Lake Wells, Florida.

- May 9, 1971: concert by Robert Lodine, Carillonneur at St. Chrysostom's Church, Chicago, Illinois.

- September 21, 1971: concert by Albert Meyer, Carillonneur at Emery Merial carillon, Mariemont, Ohio.

- September 23, 1973: concert by Richard H. von Grabow, Carillonneur at the Iowa State University campanile in Ames, Iowa.

- December 3, 1974: first time the Campanile was used to accompany the UNI Glee Club--carillon played by Jeff Stearns of Rockwell City, Iowa, and Terry Kroese of Sheldon, Iowa.

- October 12, 1975: concert by Richard H. von Grabow, Carillonneur of the Iowa State University campanile in Ames, Iowa, and UNI Carillonneur Robert Byrnes.

- June 24, 1976: concert by Leen 't Hart, Director of Carillon School in Amersfoort, Netherlands.

- May 8, 1977: UNI Carillonneur Robert Byrnes performed his master's degree recital.

- June 23-24, 1980: five formal concerts by visiting carillonneur during the Congress of the Guild of Carillonneur in North America, held at UNI.

- September 7, 1985: concert by Robin Austin, carillonneur at Grace Episcopal Church in Plainfield, New Jersey.

- September 13, 1986: concert by Frank Dellapenna, carillonneur at the Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

- October 24, 1992: Karel Keldermans and Robert Byrnes presented a Dueling Bells concert.

- October 8, 9, 2004: Karel Keldermans performed for Homecoming activities.

- April 27, 28, 2006: Karel Keldermans and organ students performed recitals.

- September 18, 2006: Karel Keldermans performed for the eightieth anniversary of the Campanile.

- Mid-October, 2007: Kui-Im Lee performed for Homecoming.

- Mid-October, 2008: Kui-Im Lee performed for Homecoming.

- April 24, 2009: Karel Keldermans performed a spring concert, including a piece written by former UNI carillonneur Robert Byrnes entitled "Reflection".

- October 31, 2013: Karel Keldermans performed by the campanile for an outdoor fall concert.

- April 23, 2015: Karel Keldermans performs a program in front of the campanile for the public.

- October 12, 2016: Midwest International Carillon Festival and Composer's Forum, featuring Karl Keldermans, Peter Langberg, Richard Strauss, Stephano Colletti, and aura Ellis as performers and panelists.

- September 7, 2018: A Friday Noon Concert is performed by Alan Beving and Bethany Brooks.

- October 25, 2019: Electroacoustic Carillon Recital: Campanology Currents, a concert is performed by Tiffany Ng, assistant professor and university carillonist from Ann Arbor.

- October 31, 2019: Spooky Scary Carillon is performed by the UNI Guild of Carillonneurs.

- March 28, 2020: UNI Student Chimers play for RodCon 2020

- October 1, 2021: The carillonneurs perform a concert for 2021 homecoming campaniling, themed Roaring 20s.

- May 12, 2022: UNI Ensemble Tours have a send off performance sung by Aidan Shorey and Emily Clouser.

Summary

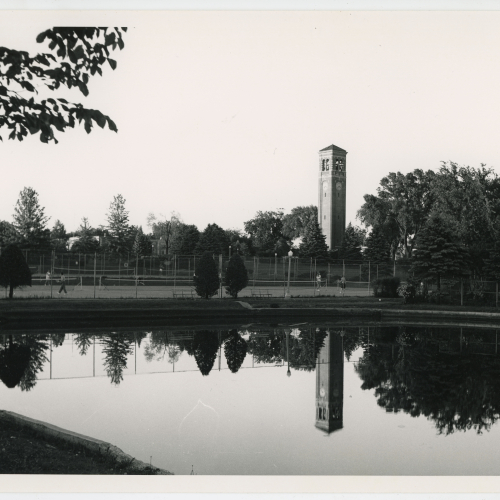

When the Campanile was built, it stood at the geographic center of the eighty-acre campus. It quickly became the most recognizable feature of the school. Though the campus has grown considerably since then, the Campanile remains figuratively at the center of campus imagery to this day.

Campanile 1994 Restoration essay originally by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, with scanning by Library Assistant Joy Lynn, October 2014; last updated January 30, 2015 (GP); citations added by Lydia L. Pakala; photos and citations updated by Graduate Assistant Eliza Mussmann April 19, 2023. Compiled by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson; September 6, 2011. Campanile Chimers and Carillonneurs essay originally compiled by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson; September 6, 2011. Updated on June 20, 2022 by Allison Guild and Alexis Stuhrenberg with information provided by Emily Clouser, President of the Guild of the Carillonneurs. Campanile essay compiled by Library Assistant Susan Witthoft; edited by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, July 1996; substantially revised by Gerald L. Peterson, September 2006; updated, January 30, 2015 (GP). Updated by Library Associate Dave Hoing, April 2018; Photos and Citations updated by Graduate Assistant Eliza Mussmann, February 11, 2022; content updated by Graduate Intern Marcea Seible, June 2025. Essays combined, content edited, and updated by Library Assistant Hannah Bernhard, January 2026.