International Students at UNI, 1896-1967

Introduction

For its entire history, the University of Northern Iowa has drawn a very large proportion of its students from within Iowa. In the early days, students from even a state or two away were unusual. For example, students from South Dakota thought that they were different enough to form their own social group, the Sioux Club. If there was an international student component on campus in the school's early years, that component came from students who themselves, or whose parents, were born in Scandinavia, Germany, or Slavic parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But those students were permanent residents and citizens of the United States. They were not visitors who would study on campus for several years and then return to their own countries. Early domestic students certainly had their own ethnic heritage and maybe still spoke Danish or German at home, but, at the Normal School, they were simply young Americans preparing to enter the American mainstream profession of teaching.

After a few years, though, at least an occasional student or two came from very far away. And, as the years passed, more international students enrolled at the college. This essay will present a broad survey of the early history of international students at the University of Northern Iowa, from about 1896 through about 1967. It will also pause along the way to feature longer looks at some of those students who made memorable and lasting impressions on their professors, fellow students, and the community.

Early Years

Around the turn of the previous century, the Iowa State Normal School, now the University of Northern Iowa, began to see a slow, but steady stream of students from other countries. In 1896, the student newspaper reported: "Joseph Mogal, of Birant, Syria, has enrolled as a Normal student. From all parts of the earth they come."

Unfortunately, there are no further mentions of Joseph Mogal in the student newspaper. Nor is he listed in school enrollment records. Perhaps he was on campus only briefly and then found another school in which to enroll. It would be very interesting to know how Mr. Mogal learned about the small Normal School in Cedar Falls, which at that time had an enrollment of only 757 students. It seems likely that Christian mission workers in Syria, perhaps Normal School alumni, alerted him to the school's strength as a teacher training institution.

In the late summer of 1900, President Seerley received a letter that brought about the school's first organized approach to international students. In the wake of the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Islands came under the control of the United States. Following that war, Fred W. Atkinson was appointed Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Philippine Islands and took up his post in Manila. Mr. Atkinson proposed to send Philippine teachers to the United States, and specifically to the Iowa State Normal School. Mr. Atkinson wrote to President Seerley:

- "It is the intention of the Department of Education to send to the United States from time to time some of the more promising Filipinos, so that they may come in contact with American social, commercial and political customs and usages. The plan is at first to select from the better class of teachers those who know some English, and to arrange for them in connection with some normal school for a year's course of practical study and observation."

Mr. Atkinson stated that the government would pay for the teachers' transportation to a school in the United States, but, beyond that, the teachers would need to cover their own expenses. He appealed to the spirit fostered in the United States by its recent victory over Spain: "Are there in your vicinity enthusiastic, patriotic American men and women who would gladly act upon committees to raise means for their board and other expenses and contribute to the success of this plan?"

That Mr. Atkinson would address his request to President Seerley was a strong testament to the growing reputation of both President Seerley and the Iowa State Normal School.

In October 1900, President Seerley published Mr. Atkinson's letter in his official column in the student newspaper. By publishing the letter in this way, President Seerley made it clear that he saw the enrollment of international students as a great opportunity, both for Normal School students and for prospective students from the Philippines. The president would need to ask the Normal School Board of Trustees if it would be acceptable to admit international students, with little or no money of their own. After all, the mission of the school was to prepare teachers for Iowa schools. But he seemed to be looking forward confidently to a positive decision from the Trustees. Even before the Trustees acted, President Seerley moved forward and made an early appeal to his student newspaper readers. He asked them to consider making monetary contributions to support these prospective students even before he had permission to enroll them in the school.

President Seerley's confidence in the Trustees was justified. On November 14, 1900, the Board voted to allow as many as six Philippine students to enroll at the Normal School without a tuition charge. The regular $5 per term tuition was certainly modest. The school could easily bear the loss of $30 per term in lost tuition. But, more important, the board decision was an indication that the school valued the opportunity to serve needy students and also perhaps to give Normal students a chance to broaden their outlook on the world. President Seerley, again appealing to the patriotic fervor of the recent war, solicited community support for the students:

- "The Education Department of the U. S. Philippine Commission desires that the charitable and patriotic persons in the United States furnish such teachers with means of support while preparing for their work as teachers in the new territories. This is the kind of work that people in this civilized country can afford to do for these people recently coming under the flag, and it is hoped that the money for their support may be readily and charitably donated."

This matter, however, seems to have been another false start for international students on this campus. There are no further references to Philippine students in the immediately following years. Nor do any Spanish-sounding names appear in student rolls.

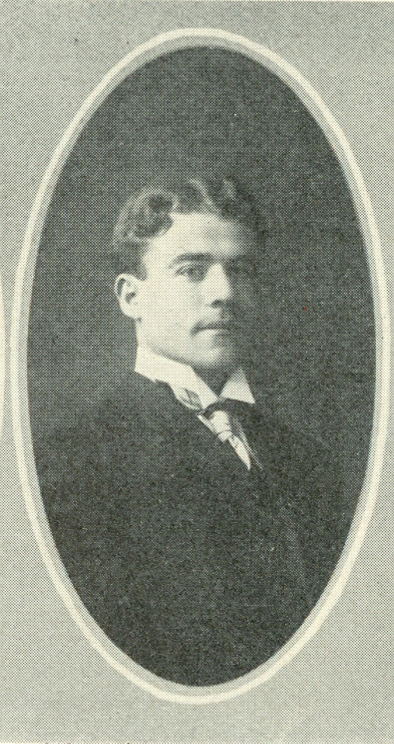

Bedros Kevork Apelian

The next reference to international students appeared in May 1907, when a student from Turkey wrote a letter in which he asked about enrolling at the Normal School. Initially, the student newspaper did not offer his name, but it did compliment the applicant on "using as good grammar and composition as many Americans with twice the education." The student was Bedros Kevork Apelian, who had been born in Syria on October 10, 1885. He was a graduate of Central Turkey College, a Christian missionary institution, and had taught two years of high school in his home country. He knew French, Armenian, Turkish, and English. Former Normal School student Effie Chambers, a Congregational Church missionary in Syria, had recommended the school to him.

Mr. Apelian enrolled for the fall term of 1907 and quickly became a campus favorite. His story deserves telling in some detail. Students liked him and did what they could to help defray his living expenses. The student newspaper wrote that "Mr. Apelian is a student and anything one can do for him is a step toward the brotherhood that should characterize all our actions." In February 1908, the Young Men's Christian Association and Young Women's Christian Association produced a series of postcards on which Mr. Apelian appeared in his native dress. Profits from the sale of these postcards went to Mr. Apelian. The article noted that in his everyday life on campus, Mr. Apelian wore Western clothing that fit in with his fellow students. Later that term, the YMCA and YWCA put on a benefit performance whose profits went to Mr. Apelian.

Bedros Apelian outlined his plans to the student newspaper. He wished to study at the Normal School for two years and then go on to a university to study theology. After completing his academic work, he would take up missionary and evangelical work in his native country. Mr. Apelian wrote a touching account of his life for the 1908 Old Gold.

He took an active part in campus life:

- joined the Orio Literary Society, where he presented papers;

- attended regional meetings of the Congregational Church;

- played right tackle on the football team;

- won an intramural track competition in the shot put;

- sang with the Troubadours Glee Club;

- took second place in a school oratorical contest;

- elected historian of the Class of 1909.

At a chapel service in late April 1909, he made a heart-breaking presentation about the devastation in Armenia, where his family still lived. He wondered if he would be able to achieve his dream of becoming a clergyman or if he would need to give up his schoolwork and take some simple job in order to send money back to his family.

He graduated from the Iowa State Teachers College (the new name of the Normal School) in July 1909 with a Bachelor of Arts degree. The student newspaper bade him a very fond farewell. The article stated that while Mr. Apelian had been in college, he took any work that he could find in order to help cover his expenses. He was an exceptionally strong student in all areas and took part in the school's "physical, its intellectual and its religious activities". The article praised "his sterling manhood, his eagerness to learn, and his marked ability". Fellow students and faculty were sorry to see him leave Cedar Falls.

Mr. Apelian continued his studies at the theological school in Oberlin, Ohio, where he planned to remain for a four year course. After a year of study there, he visited Cedar Falls while on his way to Montana, where he would be in charge of a church for the summer. He stopped again in Cedar Falls on the way back from Montana to Oberlin. His friends arranged a picnic for him, and he conducted devotional exercises before he left town. Mr. Apelian studied for three years in Oberlin and completed his course in 1912. He was then assigned to the Wykoff Heights Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, New York. He studied at Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary during the first year of his New York pastorate. His plans to return to Armenia for mission work were crushed by the continuing strife in that country. Pastor Apelian stated that he was devoting himself completely to his new assignment in Brooklyn. The Wykoff Heights church was apparently located in a working class neighborhood that included many immigrants. Pastor Apelian believed that his own background could foster a special rapport with those new Americans.

In 1914, Pastor Apelian sent a friend, Mihram Mardigian, to study at the Teachers College. Mr. Mardigian brought his cousin, Vohan Verbedian, to campus shortly thereafter.

Mr. Mardigian went to Chicago in the summer of 1915. Because he had completely lost contact with his family in Armenia, the student newspaper urged readers to drop him a card now and then in order to cheer him up.

He returned to school in the fall and graduated from the Teachers College in 1916. He lived in Detroit for awhile after graduation and then returned to the East Coast. Unfortunately, he died of influenza on October 7, 1918, before he could return to help his countrymen in Armenia.

In 1914, Pastor Apelian became a naturalized citizen of the United States. On June 30, 1915, he married Muriel Rochester in New York City. They made their home in Brooklyn. On October 21, 1916, their first child, Miriam Margaret, was born. The couple had at least two additional children. In late 1917, Pastor Apelian's congregation released him for a month to perform relief work on behalf of the Syrians and Armenians, who were continuing to suffer in his homeland. That relief assignment eventually led him to resign his pastorate, effective January 10, 1918, in order to devote his full time to that work. The student newspaper printed the letter of resignation in which Pastor Apelian stated that he believed that he was in a special position to raise money for the millions of Armenians who were being persecuted by the Ottomans. His own parents, brothers, sisters, cousins, nieces, and nephews had been killed. He wished to do what he could do to see that others were not killed or starved to death. He concentrated his efforts on raising money for relief. In a letter that appeared in the student newspaper, he wrote:

- "In the name of humanity let everybody open their hearts and contribute as liberally as their means will permit to the fund for relief of these miserable people who have been so cruelly treated. In the name of pity--give."

It is not now clear how successful Pastor Apelian's appeal was. By 1922 he had returned to the pastorate and was serving the First Presbyterian Church in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, New York. In 1950 he was serving a church in Radburn, New Jersey. He died in New Jersey in July 1969.

Victoria L. Mircheva

During World War I, there were other international students on campus. Victoria L. Mircheva was a protégé of Teachers College alumna Delpha Davis. Miss Davis had been a missionary in Bulgaria, where Miss Mircheva had been her student. The ravages of war in that area forced Miss Davis to return to the United States. When she returned, she brought Miss Mircheva with her to study at the Teachers College. Starting in late 1915 or early 1916, Miss Mircheva studied here for two years and then completed her Bachelor of Arts in sociology at a school in Ohio. While on campus, she was very active in Young Women's Christian Association work. After finishing her degree, she followed a career in social services in Chicago. She and Miss Davis visited the Teachers College campus in 1936. While in town, they stayed with Professor Selina Terry, a member of the English faculty.

Miss Mircheva was possibly the first woman international student to study at the Teachers College.

Other students

More international students began to find their way to the Teachers College during and immediately after World War I. Peruvian student Emilio Humareda entered the Teachers College in January 1915. Like most international students, he spoke to campus groups about his native country. Puerto Rican student Marco Lugo graduated with the Class of 1917, but he died in November 1918, possibly of influenza.

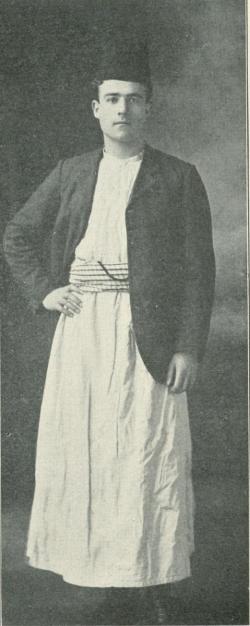

Venancio Trinidad

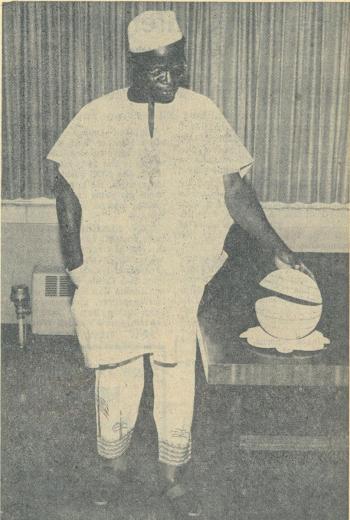

In the fall of 1919, Venancio Trinidad entered the Teachers College. Like Bedros Apelian, Mr. Trinidad, a teacher from the Philippines, was destined to become a campus star and a great student favorite. He had passed rigorous examinations in the Philippines and was selected to further his professional education in the United States. This arrangement was similar to the program proposed twenty years earlier to President Seerley by Philippine education superintendent Fred W. Atkinson. The student newspaper introduced Mr. Trinidad to its readers and concluded by saying, "Let us unite to welcome him to our country and school, and let him feel at home during his stay among us."

Mr. Trinidad was quickly elected to the Philomathean Literary Society and presented a number of papers to the group, including several on Philippine education. He was elected reporter of the society while Fred Kaltenbach was elected President. Housing for international students could conceivably have been a problem in those times when racial prejudice could take more overt forms. But Mr. Trinidad seemed to fit right in with other Teachers College students in the Tammany Hall boarding house just off campus and then later at another boarding house, the Knight's Castle. When the student newspaper gave humorous news from the various boarding houses on College Hill, Mr. Trinidad was always mentioned as part of the gang. For example, the columnist mentions that Mr. Trinidad and the boys went to Waterloo for a "Chop Suey spread" and apparently had a very good time. He was a strong tennis player and a member of the Social Science Club. In the spring of 1921 he was elected vice president of the Young Men's Christian Association, a very active social and religious group.

Mr. Trinidad was in great demand as a speaker. He was an expert on Philippine education, of course, but he also spoke on granting independence to the Philippine Islands, a moderately controversial subject in those days. In September 1921 he was elected president of the Class of 1922. That was a distinct and special honor for any student, let alone an international student. A month later he was elected vice president of the YMCA. And later in that school year he was elected president of his literary society. That winter he won the school oratorical contest, with a $25 first prize, and advanced to intercollegiate competition in Illinois. There he took second place, though some observers believed that he should have been awarded first place. Later that year, he was elected to the Teachers College chapter of Delta Sigma Rho, the national forensic society. He also took first place in a student newspaper editorial writing contest. He continued to make presentations on the Philippines to campus, local, and state groups.

Mr. Trinidad graduated at the end of the winter 1922 term. He spent a little more time in the United States to catch up on loose ends and then sailed from Seattle for the Philippines. Once there, he was appointed head of the Northern Luzon Normal School, a fledgling institution. He liked his situation, but wished that some of his stronger students could have the benefit of studying at the Teachers College. He was glad to keep up with campus news by receiving the Teachers College student newspaper. He was also happy to share his own news and experiences as the sole faculty member of his tiny, 85-student normal school. He continued to write to Cedar Falls friends over the years.

In 1927, the Philippine government sent Mr. Trinidad back to the United States. He spent the fall studying at the Colorado State Teachers College in Greeley. After that, he studied at Teachers College, Columbia University. He received his master's degree from Columbia in 1928 and then headed to Europe for further study.

In 1931, Teachers College Professor John W. Charles was asked to name the best students whom he had ever taught. At that time, Professor Charles had had over four thousand students in his classes. Mr. Trinidad was among his strongest eleven students. Professor Charles said of Mr. Trinidad: "although slight in body, he was great in mind and spirit."

It is not now known how Mr. Trinidad fared during the invasion and occupation of the Philippines by Japan, but by 1949 he was working in the Manila city schools. In the fall of 1950, he and fellow Teachers College alumnus Marcario G. Naval were able to attend a conference on the Cedar Fall campus. They were part of a three-month study tour of American educational institutions and methods. The tour was sponsored by the US State Department. In 1954 Mr. Trinidad was named acting director of the Bureau of Public Schools in the Philippine Department of Education. In 1957, the Teachers College Alumni Association gave Mr. Trinidad an Alumni Achievement Award. At that time he was noted as a retired director of the Philippine Bureau of Public Education. He died in 1963.

Horace T. C. Tu

While Mr. Trinidad was certainly the best known international student of his era, there were others on campus at that time. In the 1921-1922 school year there were also students from Canada, China, and Sweden. Chinese student Horace T. C. Tu was enrolled for at least part of the 1921-1922 school year.

Mr. Tu was involved in Young Men's Christian Association meetings, the Sociology Club, and the Science Club. In these groups he typically presented his views of conditions in China. Following his studies in Cedar Falls, Mr. Tu continue his work at the University of Iowa.

S. Peter Kuan

Chinese student S. Peter Kuan enrolled for the 1922-1923 school year. He represented the Teachers College at an international students conference in Cedar Rapids. He was active in YMCA work and gave many talks about his country to interested groups.

He graduated in 1924 and went on to Yale University to study religious education. A scholarship covered his tuition, but he worked in the dining hall to cover other expenses. He completed his study at Yale in 1926 and returned to China with the aim of establishing a school. In 1929 he wrote to the student newspaper with an appeal. He had established an industrial school for poor girls. There he gave the girls a basic education in reading, writing, arithmetic, and sewing skills. He asked his old Teachers College friends to support his efforts. Five dollars would pay the monthly salary of one of his teachers. It is now unclear what happened to Mr. Kuan's school, but by 1938 he was head of the Social Education Division, Bureau of Education, in Tsengtao, China.

Other students

Another Philippine student, Macario G. Naval, attended the Teachers College for several terms in the 1924-1925 school year. Perhaps his countryman Venancio Trinidad had recommended the school to him. Mr. Naval had already completed a bachelor's degree in the Philippines, but he earned another bachelor's degree at the Teachers College. He left Cedar Falls in January 1925 to begin work on a master's degree at the University of Illinois. He completed his master's degree there in April 1926 and, due to ill health, returned to the Philippines. By 1949 he was head of the Philippine Normal School in Manila. He and fellow Teachers College alumnus Venancio Trinidad visited the Cedar Falls campus for a conference in September 1950.

In the summer of 1928, Shorju Bose, a mathematics teacher from India, studied educational methods at the Teachers College. Miss Bose was another early woman international student to study at Cedar Falls.

Despite the prominence of some international students on campus, other international students apparently chose a quieter route. In 1929 a student who signed herself as "Emma" wrote a letter to the student newspaper in which she stated that she had heard that there were international students on campus, but that she had never met one. She suggested that the Old Gold yearbook feature a special section devoted to those students.

Leo Eleazor Stewart

By 1927, and possibly a bit earlier, Leo Eleazor Stewart enrolled in the Teachers College. He was from the Virgin Islands, though it is now unclear whether it was the British or the American portion of that island group. Mr. Stewart was a truly unusual person at the Teachers College: he was a black international student. He was elected to Pi Gamma Mu, the social science honorary society, in the fall of 1928. Later that year he became ill and was hospitalized, but was back in school for the next term. He served as secretary pro tempore of Men's Forum, the men's branch of student government. He was elected president of that group in the spring of 1929. He took part in debate and was a member of the Hamilton Club, a group dedicated to public speaking. Mr. Stewart participated in the affairs of the Catholic Student Association

Mr. Stewart graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in August 1929. A few other black students had attended the school in earlier years and had earned diplomas or certificates. However, Mr. Stewart was possibly the first black student to earn a full bachelor's degree from the Iowa State Teachers College. Following graduation he tutored Spanish in Chicago and studied at the University of Chicago. He also later studied at Miami University and the University of Mexico. By 1935 he was teaching Spanish, manual arts, and social science at Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School in Dayton, Ohio. In 1937 he married Gladys Eunice McNeel, of Chicago. They had a son, Carlos Guillermo, in 1942.

In 1953 Mr. Stewart, then still teaching in Dayton, received a fellowship to study at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. He died in about 1976.

It is interesting to speculate where Mr. Stewart might have lived while studying at the Teachers College. Given his religious faith, it is possible that the local Catholic church might have found a place for him to live.

Julian Torrano

Another student from the Philippines, Julian Torrano, enrolled in the fall of 1929. He had been in the United States since 1923 and had studied previously at Colorado State Teachers College. But he became interested in the Cedar Falls school. He noted that the Iowa State Teachers College was one of just five American teachers colleges that received high marks from the Philippine government. He planned to study the teaching of economics, geography, and reading. Then he would take a trip around the world and return to his own country to teach. While in Cedar Falls, he lived in a rooming house with Leroy Blumer, whose brief time at the Teachers College is outlined in another essay.

Finn Eriksen

There was at least one other international student enrolled in the fall of 1929. Finn Bjorn Eriksen was born in Denmark, though he had spent some time in the Danish community of Kimballton, Iowa. In some ways, Mr. Eriksen's move to Cedar Falls was probably easy. Danes had been settling in northeast Iowa, and especially in Cedar Falls, for at least forty years. They established farms, started businesses, and built homes. The Danish influence was so strong that a Cedar Falls resident could conduct most of his life in Danish in Cedar Falls, at least until the 1940s. Without much difficulty, a person could go to stores, buy insurance, attend church, buy real estate, and take care of most matters in the Danish language. There were many Hansens, Petersens, Rasmussens, and Holsts with whom to do business. Finn Eriksen fit in easily because his appearance and background were quite similar to those of many other Teachers College students. Danes scarcely seemed like "foreigners" to the Teachers College campus.

However, Finn Eriksen attracted the most attention because he turned out to be a world class intercollegiate and amateur wrestler. His exploits on the mat, usually wrestling at 135 pounds, deserve a full re-telling that is beyond the scope of this essay. But here are some highlights.

- he regularly defeated Big Ten opponents

- he wrestled at least one full season undefeated

- he won A. A. U. championships

- he captained and co-captained the wrestling squad

- he coached the Teachers College High School wrestling team

- he likely missed 1932 Olympics competition due only to an injury

Mr. Eriksen participated in many other campus activities before he graduated in 1931. After graduation, he went on to Columbia University to study for a master's degree. He then pursued a long and honored career in the teaching, coaching, and administration of physical education, and especially wrestling, in northeast Iowa. During World War II, he served in the US Navy. He was elected to the University of Northern Iowa athletics Hall of Fame in 1986, in just its second year of elections. He was also elected to the Iowa Wrestling Hall of Fame and the National Wrestling Association Hall of Fame. He died on August 8, 1992.

Su Chu Hsia

Su Chu (Eugenia) Hsia entered the Teachers College in the fall term of 1930. She had already taught in China for seven years following graduation from a Chinese normal school. She explained what brought her to Cedar Falls in a story in the College Eye in October of that year. As was typical for international students, Miss Hsia made presentations on campus about education and social problems in her country. She was active in Young Women's Christian Association work and was a member of Kappa Phi sorority. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in kindergarten education in 1931. She then went on to Columbia University, where she earned a master's degree in June 1932. She was an active member of the international student group at Columbia. She also wrote a series of five stories on Chinese home life, festivals, and markets that were published by a Methodist printing house.

Miss Hsia planned to leave from San Francisco for China on July 2, 1932. On her way back across the United States from New York to San Francisco, she stopped in Cedar Falls to visit friends. She told them that when she returned to China, she would marry Tsing Han Chen, an engineer at a Chinese electric company. She also told them that she had been offered a teaching position for the next year. It is not now clear if or how long Mrs. Chen taught after her marriage. She and her husband had three children over the next few years.

In 1938, the Japanese invasion of China put her whole family in grave peril. Somehow, Mrs. Chen managed to send a letter to her friends in Cedar Falls, Professor Alison Aitchison and former Head of Residence Mary Haight. The full text of that letter is part of the Alumnus article in which it appeared. Mrs. Chen reported that when Japanese forces approached her city in November 1938, Mr. Chen was away from home, and she had just delivered their third child. Even though she was still recovering from childbirth, she and the family--her own three children, a niece, a nephew, and a wet nurse--fled the city by whatever means they could find. They had little choice. The Japanese were advancing and, as they retreated, Chinese forces practiced a scorched earth policy and destroyed the city where the Chens lived. Mrs. Chen begged for assistance from her Cedar Falls friends, even for something as little as a can of milk for her children. Her friends responded with cash donations. How they managed to get money to Mrs. Chen in that war-torn part of the world is unknown. Perhaps they were able to use the Christian missionary network there. For months her friends feared for her safety. But by July 1939 they learned that the Chen family had managed to find refuge, after a long, harrowing journey, with a relative some distance away from their home.

The Chen family survived the war. In 1948 Mrs. Chen wrote a letter to Teachers College officials in support of the enrollment of a cousin. At that time Mrs. Chen was principal of a mission primary school in Changsha, Hunan, China. The school had twenty-nine faculty members and 630 pupils. Mrs. Chen's letter reads in part:

- "I hope my cousin can enter Teachers College because this school really makes the foreign students feel at home. I never felt homesick in Teachers College, but had the happiest life, and a wonderful time learning American life. Professors and schoolmates in Teachers College never have race prejudice. They take the foreign students in as sisters and brothers. Teachers College has given me the best American spirit which I brought back to China. It will last in China forever."

It is interesting to speculate how the Chen family fared when the Communists took over China several years later. In the eyes of the new government, strong links to the United States would have been a matter of great suspicion. But one way or the other, they did survive. In 2014 a member of the Chen family in China contacted the University of Northern Iowa Archives for information about Mrs. Chen's experience at the Teachers College. The Archives staff was happy to send both information and photographs to her family.

Other students, 1932-1945

In 1932, two more international students enrolled: Bridget Adelaide Wells from Burma and Dorothy Boyd from Puerto Rico. They seem to have been from mission or education families in those countries.

Both women graduated from the Teachers College in 1934. Dorothy Boyd married soon after graduation and remained in the United States. Bridget Wells, who was quite active in campus organizations, returned to mission educational work in Asia. Initially she went back to Burma and then later moved on to India.

In the summer of 1937, Kan Sing Ho arrived on campus. He found that he liked the Teachers College. He planned to study industrial arts and commercial education. It is not now clear how long he remained on campus. Mr. Ho was possibly the first of many Hawaiian students to study at the Teachers College. Certainly it was clear to Teachers College students of that time that Hawaii was a territory of the United States. Likewise they understood the relationship of the Philippine Islands and Puerto Rico to the United States. So, it is truly stretching a definition to call students from those places "international" students. However, that was the perception of that day. Unless a person was from the contiguous forty-eight states, he or she was perceived to be from another country.

In 1939, the Blue Key men's service fraternity, aided by a faculty committee, secured pledges of over $380 to bring a refugee student to the Teachers College. They wished to assist "a senior and one driven from his homeland by intolerable conditions--to the land of the free." Clearly the worsening conditions in Europe motivated this effort. However, it does not seem as if a refugee student came to the Teachers College campus as a result of this effort.

Just two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a most interesting article appeared in the College Eye. It is interesting for both the touching nature of its sentiments and for the attitudes that it displays. The article in its entirety appears here. According to that article, a woman of German descent, Marie Kienzle, gave a party for students with close and fairly recent ties to countries other than the United States.

Included in the group were students Marvel Jones (England), Joe Dolerich and Joe Valente (Czechoslovakia), Emigdio Urias (Mexico), Charlotte Matsuda and Lillian Watanabe (Hawaii), and Woodrow Christiansen (Denmark).

Everyone had a good time and expressed gratitude for being in the United States. It was all good melting pot stuff. But there is one troubling note to the party. Also included among the guests were Vernetta Cook and Luana Franklin. Those two young women were not from another country. Rather, Vernetta Cook was from Mississippi and Luana Franklin was from Waterloo, Iowa. But they were black. One cannot know for sure what motivated Marie Kienzle to invite these young women to a party for international students. She may have understood that black Americans were viewed as outsiders, similar to international students, and she wanted to be sure that they were included and had a good time. Given racial attitudes of that time, Marie Kienzle must have been a kind and forward thinking person. But it is distressing that the anonymous author of the college newspaper article apparently saw nothing unusual about including black Americans as a completely normal part of a gathering of international students.

The war and the resulting substantial decline in enrollment seemed to keep international student activity at a low level for a few years. Several of the international students noted in the paragraph above served in the American armed forces. But after the war, activities picked up.

Carmen Berguido

In the summer of 1946, Panamanian student Carmen Berguido enrolled to perfect her skills as a teacher of English. She was part of a trial program to see if Panamanian students could benefit from study at Iowa colleges and universities. She liked the people whom she met on campus. She said that she had feared racial prejudice in the United States. She explained that there was strict racial segregation between light and dark skinned people in public places in Panama. Miss Berguido apparently did not find that in Cedar Falls.

She enjoyed the relatively relaxed rules about dating, though she did not like the cold weather. She took part in Catholic Student Association affairs and was involved in unsuccessful efforts to build a chapel on campus. She spoke to local groups about her country. She graduated in 1948 and went on to a successful teaching career in Panama. When she returned to campus for a visit in 1977, she had fond memories of her friends, roommates, long evenings of study, and trips to Berg's Drugstore for coffee.

Norwegian Erling Slaato was on campus briefly in 1947 as part of a student exchange program. He noted that reports on German atrocities in his country during the war had not been exaggerated. Three students from Mexico--Daniel Morales, Hector Morales, and German Silva--were also here briefly that year. Lydia Landuyt, from Belgium, was on campus in 1948. She and Carmen Berguido addressed a class at East High School in Waterloo about schools in their countries. Miss Landuyt thought that American schools were much less strict than Belgian schools. She also made interesting remarks about the Belgian education system under German occupation.

David Suk Chin Kim

David Suk Chin Kim, from Korea, arrived on campus in 1948. He was possibly the first Korean to enroll at the Teachers College. He had come to the United States under interesting circumstances, and, especially as matters moved toward war in his homeland, he was often called upon to present his views. Mr. Kim had studied English at the American language institute in Seoul and had worked as a translator for the US Army. A group of Americans decided to sponsor Mr. Kim's education in the United States. Teachers College alumnus Richard Gibson steered him specifically to the Cedar Falls campus. Mr. Kim planned for a career in government service or as a newspaper political writer. He liked the peaceful Teachers College campus, but he did not especially like the public displays of affection among students. He quickly became involved in the first Iowa Intercollegiate United Nations conference at Drake University and reported on his activities in several campus venues. He participated in several panel discussions on peaceful resolution of disputes between countries. But, as matters worsened in Korea, Mr. Kim made it clear that he believed that Soviet-backed North Koreans were pushing his country into civil war. Still, he had time for some lighter things, too. Because he had gone to school with Japanese students in Korea, he was able to offer advice and guidance on Japanese customs to the campus production of "The Mikado".

In the fall of 1950, Mr. Kim was studying at George Washington University. With the war in Korea well under way, he wrote a series of informative articles back to campus, where they were published in the student newspaper. Mr. Kim received both a bachelor's degree (1951) and a master's degree from the Teachers College.

Other Students, 1948-1955

At least five international students lived in Lawther Hall in the fall of 1948: Elsie Parés from Puerto Rico and Jane Ishikawa, Karen Nakama, Adrienne Ogata, and Nancy Ishikawa, all from Hawaii. They all said that they were at the Teachers College, because it was the best school to learn how to become a teacher. They answered the standard questions from the student newspaper reporter: how do you like Iowa winter weather and what about the food?

German student Elisabeth Lehman was on campus for the 1950-1951 school year. She liked cornflakes, but found American men odd; she did not like their very short hair. Following the advice of former student Carmen Berguido, Panamanian student Melida Francesche studied English at the Teachers College during the 1951-1952 school year. She was looking forward to seeing her first snow. Hawaiian students Mike Suda and Don Moriwaki were also on campus at that time. As Christmas 1951 approached, they all recalled their holiday traditions for the College Eye.

In the fall of 1952, the Student League Board considered the establishment of a room on campus for newly-arrived international students. This room would help the new students become oriented to campus and would also provide an opportunity for the new people to become acquainted with regular students. It is not now clear if such a room was established.

Nimnuan Sinanta studied at the Teachers College in the 1952-1953 school year. She was from Thailand and was studying in the United States under prestigious Fulbright and Smith-Mundt scholarships. She already had a bachelor's degree, but planned to study kindergarten teaching methods in Cedar Falls. She chose the Teachers College at the recommendation of a missionary friend. She found the campus friendly, but missed the staple rice of her native country.

Omega Elliott, from Guam, was also on campus in 1952-1953. She was the daughter of a US military family and had spent time in the Philippines. She enjoyed dancing and took part in Newman Club and Future Business Leaders of America activity.

Takaka Oshibushi came from Japan in the fall of 1952 to study music. She became interested in the Teachers College music program after reading an article about Laboratory School teacher Melvin Schneider's method of introducing very young students--as young as first graders--to orchestral instruments. Miss Oshibushi played with the College Symphony Orchestra and performed on campus for other occasions before she received her bachelor's degree in 1955.

Other international students that year included Els Longdong (Indonesia); Coyo Primo, Maria Ceballos, Gabriela Briseno, Mercedes Velaquez, Ester Parra, Luz Alvarado, and Angela Reyes (Mexico); Abdurrahman Mors (British West Africa); and Georgina Creidy and Celia Marquez (Brazil).

The Hawaiians

The largest contingent of students generally considered to be similar to truly international students came from Hawaii. That group of students grew during the postwar years. Their names indicate that most of the Hawaiians were of Japanese descent. At least seventeen Hawaiian students studied at the Teachers College in 1952-1953. About the same number attended the next school year. Their numbers continued to be strong through the 1950s and into the 1960s. In some years there were enough Hawaiians to form their own social group, the Hawaiian Club. Other students and faculty found them to be exotic, but approachable. Their English was good, they seemed to enjoy talking about their culture, and they participated in a wide variety of campus activities. The surrounding community liked them, too. They seemed willing to perform demonstrations of their culture, especially the hula, for community groups. For several years the Eldora Rotary Club invited them to Eldora for Easter celebrations. The Hawaiians may also have benefited from a special American interest in Hawaii in the 1950s and early 1960s. Perhaps that interest had been awakened by the service of so many Americans in that part of the world during World War II. Conditions were certainly very difficult in the Pacific islands during the war, but perhaps veterans of military service imagined how beautiful the islands could be in peacetime. During the 1950s and 1960s, Hawaii became a favorite exotic location for many television and motion picture personalities and productions. In addition, it became apparent that Hawaii would soon become a state, so the islands and the people were often features in both entertainment programming and the news.

While writing his centennial history of the University of Northern Iowa, Dean William Lang told the writer of this essay that the school administration had concerns about bringing Hawaiians to campus. The administrators themselves welcomed the opportunity. However, Cedar Falls had an almost exclusively white population in the 1950s. And Teachers College students were also almost exclusively white. Nearly all of the Hawaiians were clearly Asian. Would the Hawaiians encounter racial prejudice? Would they face problems with either on-campus or off-campus housing? It turned out that the administrators' fears were ungrounded. There were no recorded incidents of racial prejudice against the Hawaiians. They fit in well and proved to be extremely popular with their classmates. They participated widely in campus organizations. Indeed, two Hawaiians were elected Homecoming queens: Barbara Miyasaki (1965) and Blanche Izumi (1968).

The Hawaiian Club survived at least into the middle 1980s, over twenty years after Hawaii had become a state.

Graduate Students and Others

The inception of the graduate program in education at the Teachers College in 1952 brought international students to campus for advanced study. These students usually already had bachelor's degrees and considerable experience in education in their own countries. They wished to improve their credentials by studying at a college with a strong tradition in teacher education. In January 1954, Yusuf Ali Qaim, from Pakistan, arrived on campus to take advantage of the new graduate program.

He had already taught in Pakistan for a number of years and wished to learn about more modern educational methods. He hoped eventually to work on a Ph. D. in the United States. He also wished to return to his family in Pakistan as soon as possible. With these motivations, Mr. Qaim worked quickly. He completed his thesis for the Master of Arts in Education degree in November 1954. Professors William Dreier, Clifford McCollum, and H. W. Reninger served on his thesis committee.

An Egyptian student, Maassouma Kazim, studied on campus that same year. She completed her thesis in August 1955. These two theses were among the earliest theses submitted and approved in the fledgling Teachers College graduate program.

In 1956, a Hungarian Student Committee was formed in reaction to Soviet repression in Hungary. Strictly speaking, this was not a Teachers College effort. Rather, it seems to have been organized by campus religious centers. Because so many international students came to Cedar Falls as a result of missionary and other religious connections, this made sense. Professor Harold Bernhard, Director of Teachers College Religious Activities, served as a member of that committee. The committee found a home in Cedar Falls for Hungarian refugee Terez Maraczi. Plans might have been to enroll Miss Maraczi in the Teachers College. But her English still needed work, so she enrolled at the Teachers College High School instead. After about a year, Miss Maraczi moved to Illinois. The committee then reorganized as the International Students Committee with a focus on bringing international students to campus, helping them to become oriented to their new surroundings, and planning inclusive social activities.

In 1956 Mahtalat Rashidi arrived on campus. Mrs. Rashidi, from Iran, was one of the first of many Iranians to study here. She had been the principal of a school in Abadan and looked forward to working on a master's degree. She was impressed by the friendliness and helpfulness of the Americans whom she had met. Mrs. Rashidi seems to have returned to Iran before completing her degree here.

In the summer of 1957, there was an "International Dinner" for summer school students. However, this seems to have been a production of the college food service rather than something prepared by international students.

Four students from Puerto Rico, arrived for study under a Puerto Rican government grant in the fall of 1957: Catalina Lopez-Rodriguez, Teresa Rivera-Noris, José Sierra, and Juan Manuel Aguayo. They were juniors and seniors with some teaching experience. They were looking forward to seeing snow, but they were a bit daunted by how fast Teachers College students seemed to speak English. These students became acquainted with Alicia Visuetti, a student from Panama, who was taking graduate courses in educational supervision. Miss Visuetti chose to study at the Teachers College because of its sound reputation and also because of its isolation: she wanted to concentrate on her English skills and thought that there would be few, if any, speakers of Spanish in Cedar Falls.

In 1958 another Iranian student arrived. Rouhollah Youssefyeh was from Tehran and had worked there as a bookkeeper for two years in order to earn enough money to study mathematics and physics in the United States. He found Americans to be hard-working and interested in education. During his year on campus he took part in Speech Activities Club activities. Also in 1958 Japanese student Yaeko Sakuramoto arrived for a year of study in home economics. She liked the helpfulness of her classmates and the relative informality between professors and students.

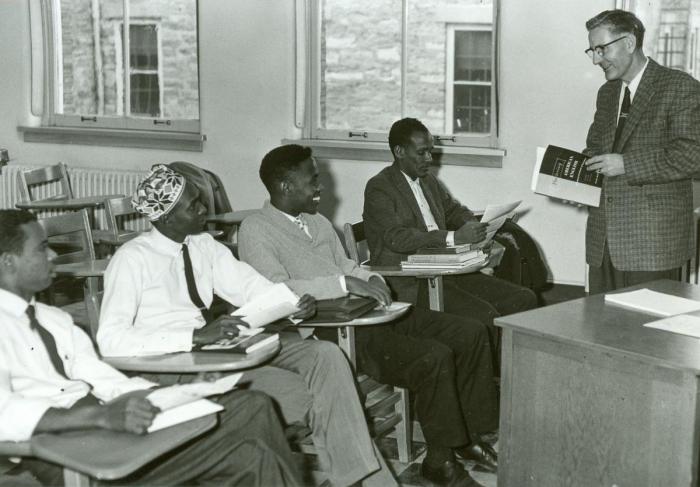

The 1959-1960 school year brought two students from very distant places: Jagdish Goyal from India and Haile Abedjie from Ethiopia. Mr. Goyal was a New Delhi school principal. He worked as a graduate assistant for Professor Melberg's educational television course and also assisted his advisor, Professor Gordon Rhum. Mr. Goyal was completing his master's degree. Mr. Abedjie had been planning to study at the Teachers College for two years before he finally overcame bureaucratic obstacles and began his work. He studied elementary education.

Later that year there was a drive on campus to raise money for both current and future international students. A group called the International Affairs Association joined the effort, which continued into the summer. The specific object in this case was to assist four Nigerian students who wished to enroll in the fall term of 1960. The outcome of that effort is unclear. It does not seem as if those four Nigerians enrolled at the Teachers College at that time, though they may have been among those who enrolled at a later date.

Said Dajani, from Jordan, had been doing Arabic clerical work for the United Nations in New York City when he became acquainted with Professor George Poage. Professor Poage, who had strong connections with United Nations activity and programs, invited Mr. Dajani to attend the Teachers College. Mr. Dajani enrolled in 1960. He ran with the cross country team and graduated in 1962. A student from Thailand, Banlue Tinpangka was also in school at that time. He participated in student government and graduated in 1962. He planned to pursue a doctorate at another college in the United States. Malayan student Anna Lee Swee Yin enrolled in school in the fall fo 1960. With a government scholarship, she planned to study in the United States for a year and then return to Malaya to continue her teaching career.

Additional Iranian Students

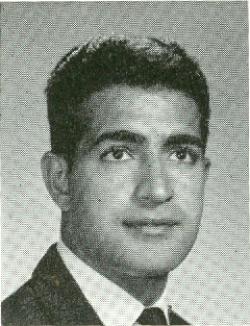

Also in 1960 Iranian student Houshang Bozorzgadeh enrolled. Mr. Bozorzgadeh was a world class table tennis player. He won the Iowa state table tennis tournament in 1961. Compiling a perfect record, he was named the outstanding player at the national men's table tennis tournament in 1962. He continued his extraordinary achievements in table tennis over his last two years at the Teachers College and sometimes gave demonstrations of his amazing skills on campus. He graduated in 1964 and was eventually elected to the United States Table Tennis Hall of Fame.

Another Iranian athlete, Esfandiar Sattari, enrolled at the same time. Mr. Sattari was the Iranian national record holder in the javelin throw. He competed with the Teachers College track team and graduated in 1964. In 2006 he was inducted into the UNI athletics Hall of Excellence.

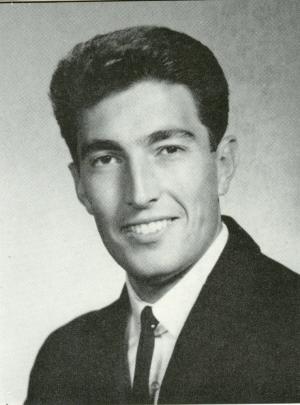

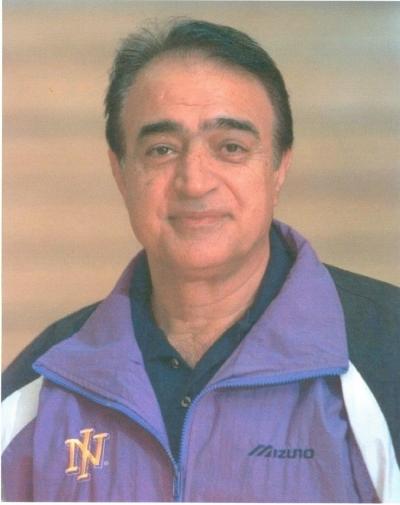

Iradge Ahrabi-Fard, an international student from Iran destined to an extraordinary career at UNI, entered school at this same time. Mr. Ahrabi-Fard had great skills in volleyball and soccer. He and his countryman Esfandiar Sattari were a powerful force on their residence hall volleyball team in intramural competition.

Mr. Ahrabi-Fard took on the difficult duties of president of the Cosmopolitan Club. He attempted to involve domestic students in the group's activities while keeping international students from many countries happy. He also led the Cosmopolitan Club soccer team and was a member of the College Eye staff.

He received both his bachelor's and master's degrees at the State College of Iowa and then earned his Ph. D. at the University of Minnesota. Mr. Ahrabi-Fard taught and coached at the Malcolm Price Laboratory School from 1972 through 1981. He then became a member of the College of Education faculty and head volleyball coach. As coach, he compiled a record that is unlikely ever to be excelled.

- Team record, 503-142-4

- Ten league titles

- Conference coach of the year seven times

- National coach of the year, 1999

- UNI Athletics Hall of Fame, 2002

- Missouri Valley Conference Hall of Fame, 2011

After resigning as head volleyball coach in 2001, Professor Ahrabi-Fard returned to teaching in the UNI School of Health, Physical Education, and Leisure Services.

Getting Organized for International Students

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Teachers College students and campus organizations seemed to develop a more systematic approach to international students. Student government and various clubs arranged panel discussions involving international students on a regular basis. Sometimes the panels dealt with a particular issue, such as the recognition of Communist China by the United Nations. Sometimes discussions were more broad. There were also more regular fund drives to assist in recruiting new international students and to help support those currently enrolled.

In 1961, Registrar Marshall Beard talked about the enrollment process for international students. He said that only a small percentage of letters of inquiry--perhaps ten percent--from international students actually went forward. Most letters were from potential students who needed a full scholarship or who did not plan to teach. The Teachers College did not have such scholarships. And teacher education was its only curriculum. So those students did not qualify. If Mr. Beard believed that potential students did have the means, qualifications, and intentions to attend school, then he forwarded an application to them. In cases in which a student's government would furnish funding, he corresponded directly with that government. Mr. Beard stated that he was very interested in increasing the number of international students at the Teachers College for several reasons:

- "First, because it is a very worthwhile experience in terms of the foreign student. Then, because it is helpful to our student body. I want to see good students, leaders, and potential leaders from other countries admitted to ISTC. I want community organizations to help these students get an education, but I don't want our foreign students exploited. They are not here to provide free programs for every organization in the area--they are here as students and cannot afford to go out every night as a kind of side show."

Professor Alden Hanson, who had been appointed as a special advisor to international students, echoed Mr. Beard's thoughts on the value of international students on campus:

- "When one of our students gets to know one of the foreign students really well,

not as the student from 'this country', or the student from 'that country', but as a

person, then a feeling of a real tie or interest with another culture, nation, or

people develops . . . This works both ways, I am confident."

When President Maucker summed up his first eleven years in office in 1961, he specifically mentioned international students as a source of knowledge for domestic students. International students could provide practical knowledge about things that domestic students had learned only in textbooks.

Four students from Somaliland arrived on campus to study education in the spring semester of 1961. Ethiopian student Haile Abedjue helped them find their way around campus. One of those students, Ahmed Shire Mohmud, took issue with a film on the Belgian Congo that had been presented on campus. He believed that the film took a colonial point of view that did not accurately reflect what Africans themselves had achieved.

The 1961-1962 school year saw at least twenty-two international students enrolled. Among them were Mr. and Mrs. Naim Gupta, who came from India to study at the newly-named State College of Iowa. Mrs. Gupta was a high school teacher who would study for her master's degree. Mr. Gupta would pursue work in guidance and counseling. They had the unfortunate experience of losing a suitcase of Mrs. Gupta's saris in transit, but it was eventually recovered.

Mr. and Mrs. Naim Gupta, their lost and found suitcase, and Mrs. Gupta's recovered saris

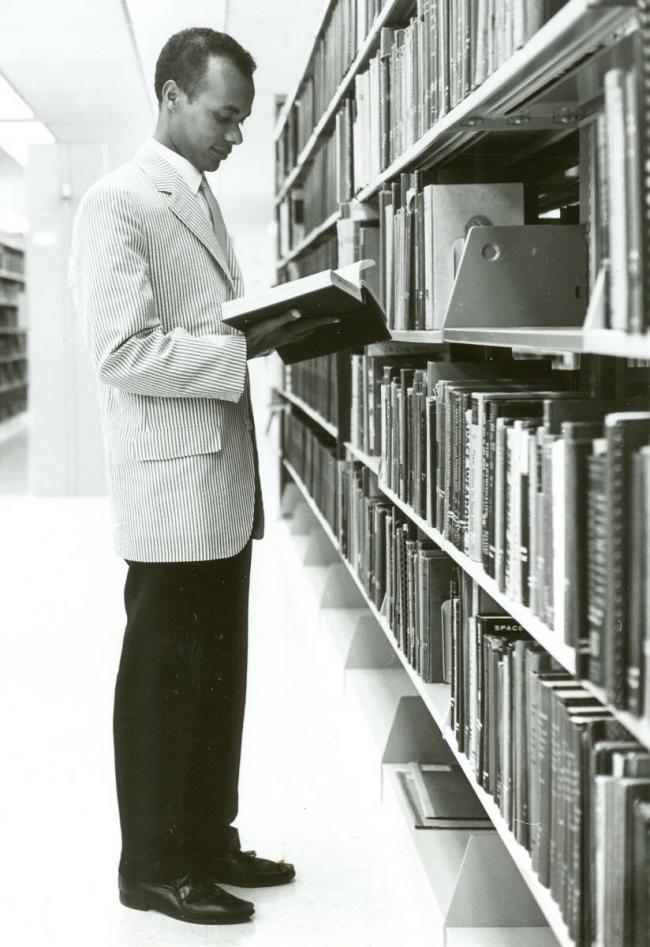

Another student was Clement Mbaoma Ezeanii, from Nigeria. Mr. Ezeanii tried to help students understand that the situation in Africa was changing very rapidly. He praised Americans for their "friendliness and ease in mixing".

As the number of international students grew, certain problems arose. For example, in those days the college residence halls closed over interims and holidays. Where would international students live during those times? International students' plans for the Christmas break, for example, sometimes sounded bleak. In response, the school found several off-campus homes where they could stay. There was also a brief exchange of letters in the student newspaper in 1964 that stated that both African-Americans and black international students faced racial stereotyping and prejudice. And, unlike African-Americans, black international students did not have local friends or relatives for support. Later that year the Cosmopolitan Club, made up of international students, petitioned to have a representative in student government. Club members said that they were often not socially accepted on campus. Domestic students went home for the weekend, while international students were left alone in the residence halls. Student government responded to the expressed needs of international students by suggesting:

- Keeping residence halls open during breaks

- Screening roommates for international students

- Establishing orientation programs on American life

- Establishing host family arrangements

- Making international newspapers available

- Hosting informal suppers so that international students could become better acquainted

Several of these recommendations, including informal dinners and roommate screening, were put into practice with some success over the next few years.

In the fall of 1964, four Liberian students, studying here under a Liberian government program, received graduate certificates for studies of school boards and school systems in Black Hawk and Linn Counties. They attended school board meetings, visited many schools, and conferred with school officials. They attended several national conferences before returning to Liberia.

In 1965 Nigerian student Celestine Chioma took time to write eloquently about some of the problems faced by international students. Knowledge of English seemed to head his list and to be a basis for other problems. He found that domestic students and faculty spoke too quickly for some international students to understand. When international students asked a professor a question, they believed that they became an unwanted center of attention among classmates. They found it difficult to have informal discussions about assignments with classmates, again because of communication problems and maybe also because of social barriers. Mr. Chioma explained that American testing and evaluation processes were quite different from those to which many international students were accustomed. All of these factors tended to drive international students to study alone, forego opportunities for recreation, and increase loneliness and isolation. Mr. Chioma did not blame the State College of Iowa specifically for this situation. He believed that it was inherent in the experience of just about any international student in any educational institution. Mr. Chioma ultimately received his bachelor of science degree from another school, but in 1967 he wrote a letter to the College Eye that expressed his profound gratitude to his advisor, the faculty, the administration, and the Cedar Falls community for their contribution to his education.

In the spring of 1965, the residence administration organized a series of orientation sessions for students who wished to room with international students. These sessions included presentations by international students to local students, followed by discussion. Residence hall staff then interviewed local students and chose those who would be paired with an international student in the fall term. The community also got involved with international students in the middle 1960s. The Black Hawk Union Council organized annual dinners for international students, including high school exchange students. General chairman Imre Takacs hoped that events such as this would foster understanding between local citizens and people from around the world.

In 1967, the State College of Iowa became the University of Northern Iowa. And, as campus unrest began to rise in middle and late 1960s, local interest in international students seems to have been pushed aside for a few years. With a number of organizational structures in place to help support international students, both the school's administration and local students seemed to turn their attention to pressing domestic matters. International students continued to enroll, but they did not seem to be quite as prominent or unusual as they had been in the past.

The experience of international students at the University of Northern Iowa after 1967 must be the subject of another essay at another time.

Summary

--What was an international student?

The definition of an international student seems clear: a person from another country, who is studying at an educational institution. However, for many years the operating definition at the Teachers College was much broader than that. That definition included students from territories, commonwealths, and dependencies of the United States, such as the Philippine Islands and Hawaii. In a distinctly Iowa-based institution, with a statutorily limited mission, students of other races and non-Western cultures were so different that, in domestic students' perception, they might as well have come from another country. Consequently, geographical and political borders seemed to matter little: if a student came from outside of the contiguous forty-eight states, he or she was an international student.

--Where did international students come from?

In the earliest days, the sample size is so small that it is hard to make generalizations about international student origins. A number of early students came from the Middle East, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and China. Most of these students arrived as a result of missionary referrals. Some of these students brought friends or relatives here as well. But by the 1930s there came to be a small, but broader distribution that included students from European countries as well. Following World War II, Hawaiian students constituted the largest number of students from distant places. They continued to be the majority through the 1950s, though many other countries were represented as well. With the growing popularity of graduate study, students from Africa, especially from Nigeria and the Horn of Africa, began to arrive.

--Why did international students come to the Cedar Falls school?

Some international students came to the United States because of war, persecution, and severe repression in their homelands. They came to this country, because they were in fear for their lives in their own countries. Usually these students came specifically to Cedar Falls due to contacts with Christian missionaries in their home countries. Mission work was a common occupation for Teachers College graduates at that time; alumni serving as missionaries were scattered across the world. So, sometimes the missionary who made that contact was specifically a Teachers College alumnus. A missionary could be sure that his or her protégé could find appropriate YMCA, YWCA, or religious denominational support on the Teachers College campus. At least among Teachers College international students through the 1930s, this religious connection was almost universal. After that time, several other factors entered into the picture. For example, if an international student was successful at the Teachers College, he sometimes persuaded friends, professional colleagues, or relatives to enroll as well. Eventually, national governments officially recognized the high quality of teacher education in Cedar Falls and sent their best students to the campus.

Escaping life-threatening situations in their homelands was a first priority. However, once they secured safe haven, international students could turn to being students. All of the early international students made it clear that their firm intention was to learn to be a better teacher--either secular or religious--and return to their native land. There they would improve conditions for their countrymen. The Teachers College was an attractive school in which either to begin or to enhance teaching skills. Teacher education was, after all, the sole purpose of the school until 1961. In the 1910s and 1920s, the reputation of the Teachers was genuinely international. When graduate programs began to be offered in 1952, many students came to campus for advanced study.

--What did international students find at the University of Northern Iowa?

Nearly all international students found a welcoming atmosphere. Many domestic students were curious about the visitors and their countries, but they also showed respect. A large number of international students readily took part in religious activities, student organizations, student government, and even important school programs such as debate, oratory, and athletics. The student newspaper would almost certainly publish a feature article about them. Although the articles were entirely predictable--food, family, customs, weather, reasons for enrolling--they served the purpose of introducing newcomers to the broader campus community. Some international students found that their language capabilities limited their classroom success and social acceptance, but many persisted to earn bachelor's degrees. In days when earning a degree was not the course taken by most domestic students, it is remarkable that so many international students earned degrees.

Especially in the early days, and persisting at least into the 1960s, international students were called on by groups, both on and off campus, to talk about their countries. Most international students likely enjoyed getting to know their fellow students and learning about the local community in these program settings. Most seemed to have brought clothing and other display items with them for occasions such as these. Some international students led groups in singing songs from their countries. Some, such as the Hawaiians, could even entertain with dance. Classmates and people from the community were genuinely interested in the international visitors and their cultures. Both sides learned and benefited from getting together socially. There was, however, at least some danger of exploiting international students with these kinds of activities. They were students, after all, with serious classroom responsibilities. As Registrar Beard warned in 1961, the students could not afford to be used "as a kind of side show" to entertain the community. Still, most students seemed to achieve a kind of balance in this area.

By 1960, the school began to take a more organized approach to international students. Initially more as a matter of special interest, and then later as something approaching a responsibility, members of the faculty such as Professors George Poage and Alden Hanson paid special attention to both the academic and social sides of international students' lives on campus. These faculty members served as advisors to special interest groups for international students and served as sounding boards for their concerns. Likewise, student government sought and accepted a certain amount of responsibility for the welfare of international students. On a regular basis, for example, student government organized fund drives to assist these students.

In the 1960s, several international students from Africa were forthright in expressing difficulties experienced by some international students. Against a backdrop of developing African nationhood and a growing awareness of civil rights, there were hints that black Africans and black Americans faced similar problems.

--What did international students receive?

Most international students received what they were seeking: academic credentials, improved English skills, and a look at a portion of the United States and its people. Some became campus stars; others were content to pursue their studies quietly. They went home with good stories to tell and a greater understanding of international relations. Early international students had the greater opportunity to make an impression on campus because there were so few of them. Later, when there were twenty or twenty-five international students on campus, they could go almost unnoticed. Over the course of time, expectations broadened on both sides. Especially following World War I and maybe even more so following World War II, both local and international students came to a greater realization that national or even continental isolation was no longer possible. People needed to understand each other better in order to avoid global conflict.

Conclusion

International students began to attend what is now the University of Northern Iowa when the school was fully thirty years old. Even in those early years, both international students and domestic students benefited from the experience. Early international students were distinct campus curiosities. At a time when many local students, before enrolling at the Cedar Falls campus, had seldom traveled much farther than their own home county seat, a visitor from China or the Ottoman Empire must have been amazing. Early students treated the visitors with respect and a certain amount of wonder. Many early international students were exceptional performers with extraordinary personal histories prior to their arrival on campus. Local students, usually quite young and inexperienced, had the opportunity to learn a great deal from them.

World War I brought a greater appreciation for international relations. Many Teachers College students, alumni, and faculty--or members of their families--served overseas during the war. Most came home with a changed and expanded view of the world beyond the Teachers College campus. They seemed to take a greater interest in world affairs. A steady stream of international students helped to keep this interest alive.

The relationship between international and domestic students was not completely focused on academic matters. They also got together for athletics, religious activities, student government, entertainment, and good food. They learned about each other's culture in a variety of experiences. When problems arose, both students and, in later years, the school attempted to assist in finding solutions.

After an understandable lull in international student enrollment during World War II, things picked up substantially in the late 1940s and into the 1950s. Students from Hawaii led the way with many others from Iran and the Middle East. African students followed. Some of these students were attracted by the new graduate program, but most focused on undergraduate study.

The international student program at UNI has been a great success for a long time. What international students learned here and then took home made significant impacts on educational systems in many parts of the world. What they left here has been a positive and expanded world view among generations of young Iowans.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, scanning by Library Assistant Joy Lynn, March-April 2015; last updated, April 16, 2015 (GP).