Getting Sick at School: Influenza and Other Illnesses at UNI, 1876-2009

Introduction

Illness, ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening disease, is a natural part of human life. Consequently, the H1N1 influenza virus threat was not the first potentially widespread illness or disease faced by the University of Northern Iowa community. Since it opened in 1876, the institution has seen its share of both mild and serious illness among its students and employees. Some diseases are more prevalent and spread more rapidly and noticeably in institutions such as schools. In the early days of the school, students and faculty experienced a range of illness, from vaguely described "eye trouble", through recurrent outbreaks of measles and mumps, and to more serious diseases such as tuberculosis and smallpox. Toward the end of World War I, they experienced the devastating effects of the influenza pandemic of 1918. While prevention and better treatment now limit the effects of these diseases, some of them must still be treated with care.

Some illnesses that were once common or serious in the university community are now rare or of mild concern. Some illnesses have come in recurrent waves spreading out from the general population. Some illnesses have arisen only in recent years. With advances in medical research and a clearer understanding of methods of infection, treatment, and prevention, the ability of the institution to respond to various illnesses has changed over the years.

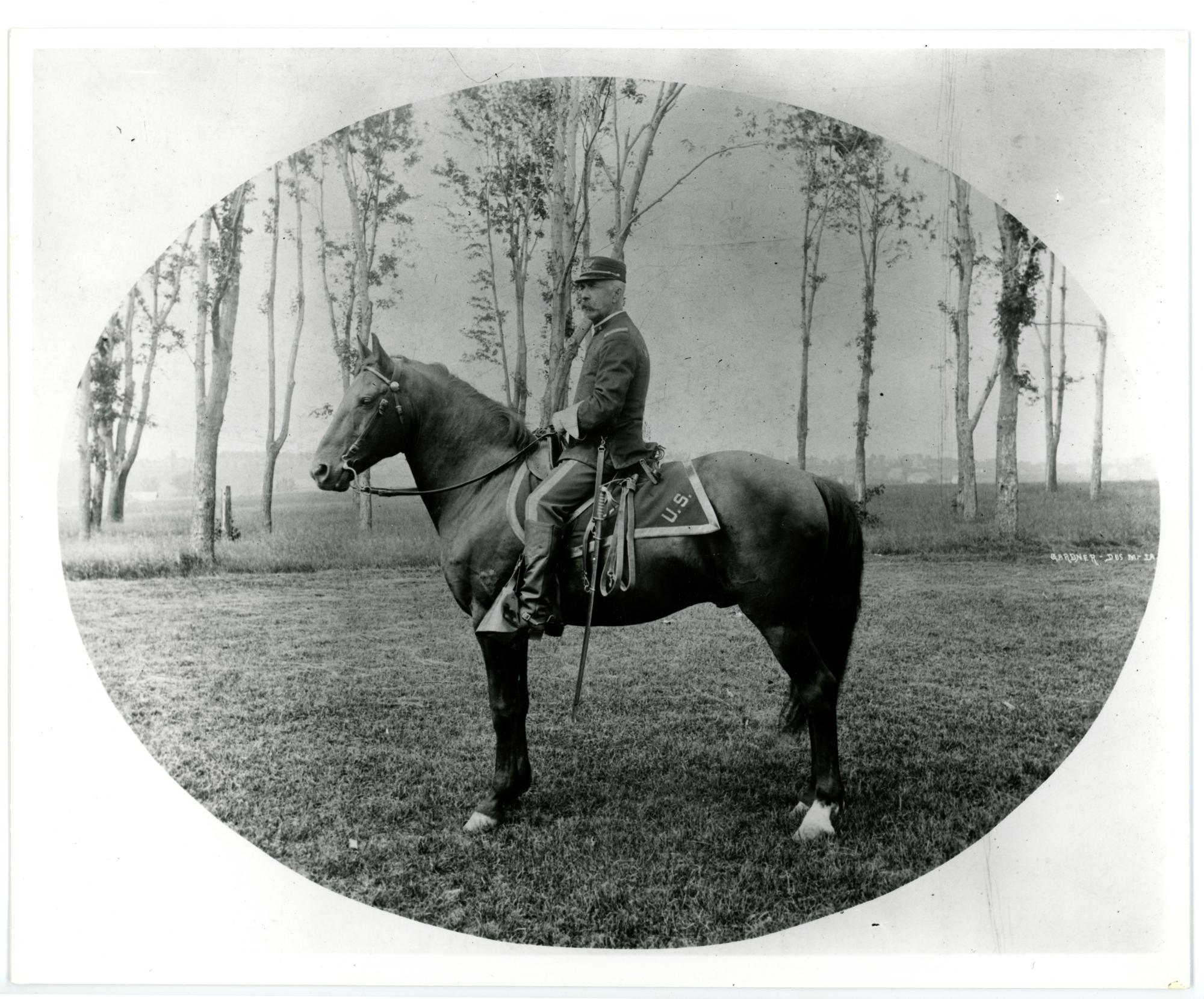

When the Iowa State Normal School (now the University of Northern Iowa) opened in September 1876, living conditions were about what could be expected for that time and in that situation. The original building, Central Hall, had been built in 1869 as a home for the orphans of Iowa veterans of the Civil War (Wright, 1901).

After the orphanage closed, the building was hastily modified during the summer of 1876 to accommodate college students. Living quarters were cramped and poorly ventilated. Running water was limited to central pipes in the dormitory areas from which hot and cold water could be drawn into pitchers. The pipes provided sufficient water for a quick wash-up, but certainly not enough for baths on a regular basis. It was not until 1893 that the Young Men's and Young Women's Christian Associations arranged to have bath tubs installed in Central Hall (McManus, 1893). Toilet facilities were primitive, and, at least initially, probably outdoors. Food was prepared in a central kitchen and served in a central dining room. Some of the food was raised on the western half of the original forty-acre campus. The food was basic and nutritious, though not especially tasty. Conditions in rooming houses were seldom better.

Few students at that time would have thought that these conditions were especially rough. Most had grown up on farms and in small towns with similar living conditions. Those who came from large families would have been accustomed to sharing space with many others. The students were likely to have been brought up in relatively isolated social conditions because people lived much more locally in those days. Transportation and travel opportunities were limited. Family responsibilities kept people close to home. Young people of that time would likely not have moved in social circles much beyond their family, their church, their country school, and the nearest towns. They probably caught and developed a resistance or immunity to whatever diseases were most common in their own locality. But, as newcomers to the Normal School, they faced a wide range of illnesses to which they had not been exposed, and for which the primary remedy was rest.

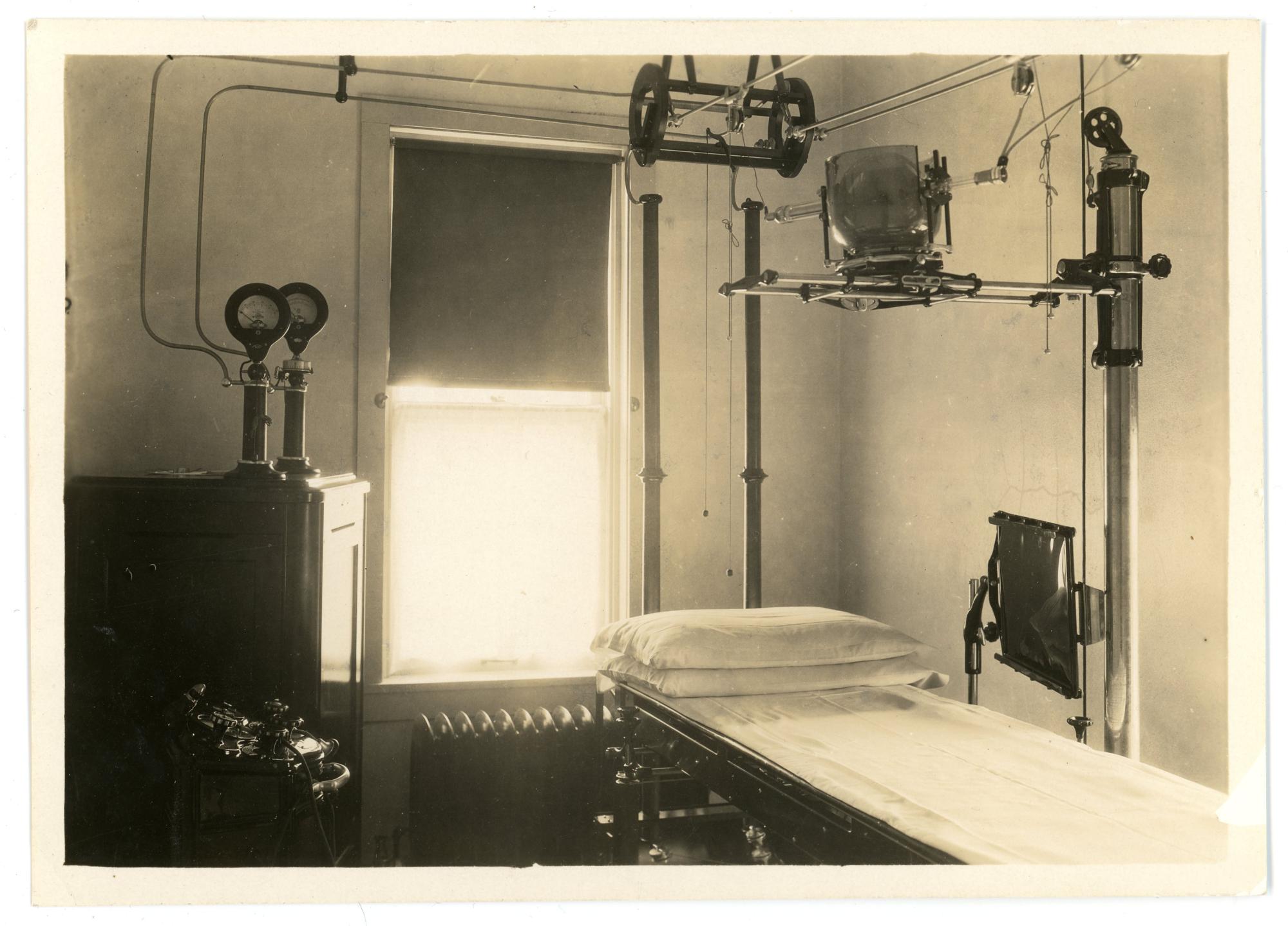

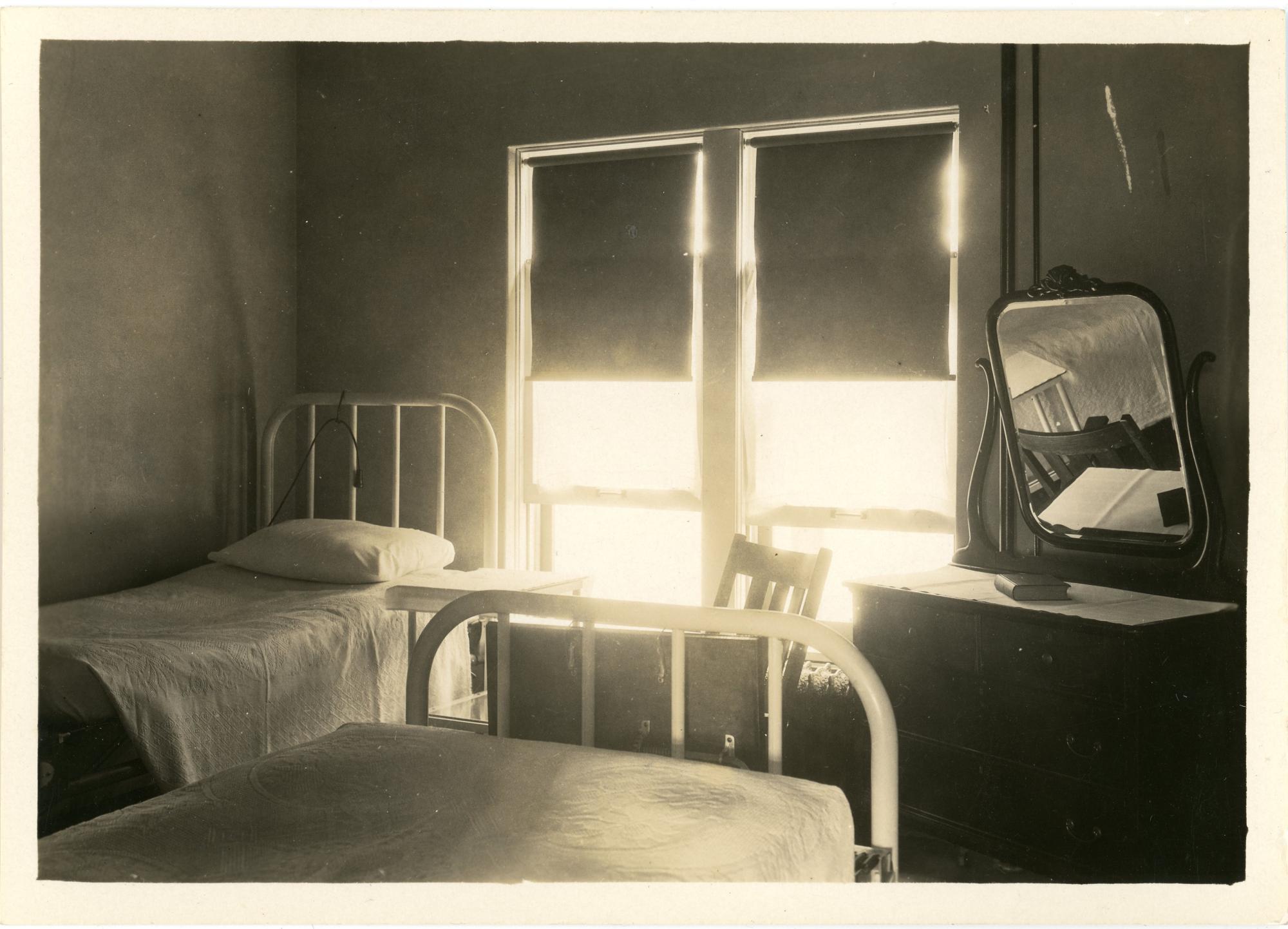

Certainly, both living standards and medical practice improved over time. For example, in 1909 the school set up the first campus hospital in what is now the Honors Cottage ("Finance Committee here," 1909). Purposely built and professionally equipped health care facilities followed shortly thereafter, including the building that came to be known as the College Hospital.

In 1914 the college began building its first modern dormitory, Bartlett Hall, largely as a measure to ensure the health of its women students ("Ground is broken," 1914). In addition, the school hired its first Director of Health Services, Dr. Franklin Mead, in 1920 ("Dr. Frank N. Mead," 1920). The health services program continued to be enhanced over the years.

This brief essay will consider the effects of a number of illnesses on the university community and the ways in which the school responded. This essay will be, for the most part, a student's eye view of the situation, rather than a scientific or statistical report. Consequently, there will be some imprecision and ambiguity. Was a bad cold misdiagnosed as influenza? Was a reported case of smallpox really just chicken pox? What variety of measles did students have during a particular epidemic? In most cases, it is impossible to say for sure at this point. Rather, this essay will try to describe what the people at the time believed they were experiencing.

Note on institutional names: The University of Northern Iowa has had four names: the Iowa State Normal School (1876-1909); the Iowa State Teachers College (1909-1961); the State College of Iowa (1961-1967); and the University of Northern Iowa (1967-present). This essay will use the name that is appropriate to the era under discussion.

Eye Trouble

The most commonly reported illness in the early days of the school was "eye trouble". Reports of this problem appeared in the earliest issues of the student newspaper in 1878 and remained a staple of local reporting over the next thirty years. A report from the May 1, 1880, Students' Offering is typical:

- "The Second Year Class regrets the loss of one of its leading members, Miss

Ella McNean, who was compelled to return home on account of her eyes." ("Ella McNean," 1880).

The articles seldom offer significant descriptions of the symptoms of eye trouble. The words "sore" or "strained" appear occasionally in the articles, but there is little further description. Apparently everyone of that day understood what eye trouble was. The problem was severe enough to cause some students to leave school, at least for a while. The overall assumption of the articles was that eye trouble was caused by too much study. The only remedy seems to have been a rest from that study, usually at home. The problem also affected several members of the faculty, including Library cataloger Clara Drenning went home for a few weeks in 1904 due to eye problems. She returned to work, but in 1906, she resigned her faculty appointment and returned home to Galena, Illinois. The Normal Eyte reported:

- "Miss Drenning has been forced to resign her work as cataloguer because of the condition of her eyes. Everyone deeply regrets her leaving but hope that a rest may prove beneficial." ("Miss Drenning," 1906).

After thirty years of reports much like this, the subject of eye trouble completely disappeared from the student newspaper by about 1910. At this remove, it is hard to say exactly what this eye trouble was. Quite likely it was a number of things which manifested themselves as visual disturbances and discomfort. Could it have been a persistent infection, such as conjunctivitis, which can now be treated easily, but was difficult in the days before antibiotics? Could it have been the aftermath of childhood disease? Could it indeed have been, as the articles sometimes suggest, due to eye strain?

Intense study, in less than ideal light--probably kerosene lamps in many rooming houses--could not have been easy on the eyes. Or might it, on some occasions, have been a good excuse to leave school when things were not going well? If a student said that his or her eyes hurt, could anyone quarrel seriously with that? Perhaps better lighting conditions, better medical treatment, and better reading glasses helped, but, for whatever reason, "eye trouble" seems to have disappeared as a student health problem after 1910.

Tuberculosis

Students of the early years of the Normal School also faced some quite serious diseases, among them smallpox and tuberculosis. These two diseases killed millions of people over the course of history. By the second half of the nineteenth century, medical science was beginning to understand both the causes and the infectious vectors of tuberculosis and smallpox. But effective treatment was limited, and cures could not be assured. Few, if any, students died of tuberculosis while they were enrolled at the Normal School. That is likely the result of the nature of the disease, which often progressed over a relatively long period of time. But certainly many students had been exposed to tuberculosis before they came to the Normal School. Some had recovered from mild cases when they were children. Some might also have been active carriers of the disease. This would have been typical of just about any population in Iowa.

While they were asymptomatic as students, some later developed tuberculosis and died of the disease. From the earliest days of the school down through World War I, the student newspaper reported at least thirty deaths among former students due to tuberculosis or consumption, as it was sometimes called. Those who died were nearly all in their twenties; they had attended college and were just beginning their careers or families. A 1913 article in the College Eye on the death of former student Charles Oliver Basham is typical:

- "Mr. Charles Oliver Basham . . . died on the afternoon of January 30. He attended the Teachers College from 1907 to 1910, was a member of Philomathean Literary Society, and was an active member of the Y. M. C. A. Oliver . . . was one of those active and industrious men whom we like to meet. While in school he earned all his expenses and since leaving Cedar Falls has been striving onward and upward, striving to reach a high ideal of service which he had set for himself. Last year he attended the law school at Valparaiso, Indiana, and this year pursued a course of study in the Indianapolis law school. He contracted tuberculosis at school and was brought to his home about ten weeks ago. Since then he has steadily declined and death overcame him last Thursday. He led an exemplary, earnest Christian life without fear for the future." ("Former students dies," 1913).

Some of the news about former students with tuberculosis followed a pattern. There would be a news note that a student was moving to the West, Southwest, or a higher altitude "for his health." That was almost always the code that someone had tuberculosis. Sometime later there would be a notice of that person's death. That was the case for former student Anna Wormhoudt. In 1906 the newspaper included a note that she had moved initially to Colorado and then to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to improve her health, after an attack of pneumonia followed by a tubercular condition. She reported that she was feeling better after her move to New Mexico ("Ana Wormhoudt, 1904). But in 1907 there was a notice of her death. She had returned to her family in Pella, Iowa, when her health again deteriorated and the outcome of her illness became clear ("Ana Wormhoudt", 1907).

While doctors of that time had begun to have a better understanding of the causes and course of tuberculosis, treatments were limited: fresh air, relative isolation from other people, and a drier climate were about all that they could recommend. Two experts on tuberculosis spoke on campus, one in 1909 and the other in 1912. In 1909, Dr. George Whittaker warned especially about the spread of tuberculosis via infected cow's milk ("Lecture on tuberculosis", 1909). In 1912, Dr. Kepford, who was in charge of Iowa's battle against tuberculosis, praised Teachers College alumni. He said that schools run by Teachers College alumni followed good sanitation practices, which helped limit the spread of the disease ("Dr. Kepford talks," 1912). In 1917 Dr. Kepford wrote back to the student newspaper to warn students of a possible increase in the spread of tuberculosis due to the upheaval of World War I ("Urgent watchfulness," 1917).

After World War I, there continued to be news about tuberculosis, but the tone had changed. First, there were no obituaries. There were still occasional notes about people who had contracted the disease, but the emphasis was on active treatment and recovery. As part of this effort, Teachers College students started a campus Christmas Seal program in 1922. The Christmas Seal idea had started in Denmark in 1902 and spread to the United States by 1907. People would buy the seals and place them on their Christmas cards. The money from the sale of the seals would go toward relief for those with tuberculosis and toward research on a cure for the disease. Christmas Seal campaigns were a regular part of student and faculty charitable efforts on campus through at least 1946 ("Christmas Seal sale is opened," 1924).

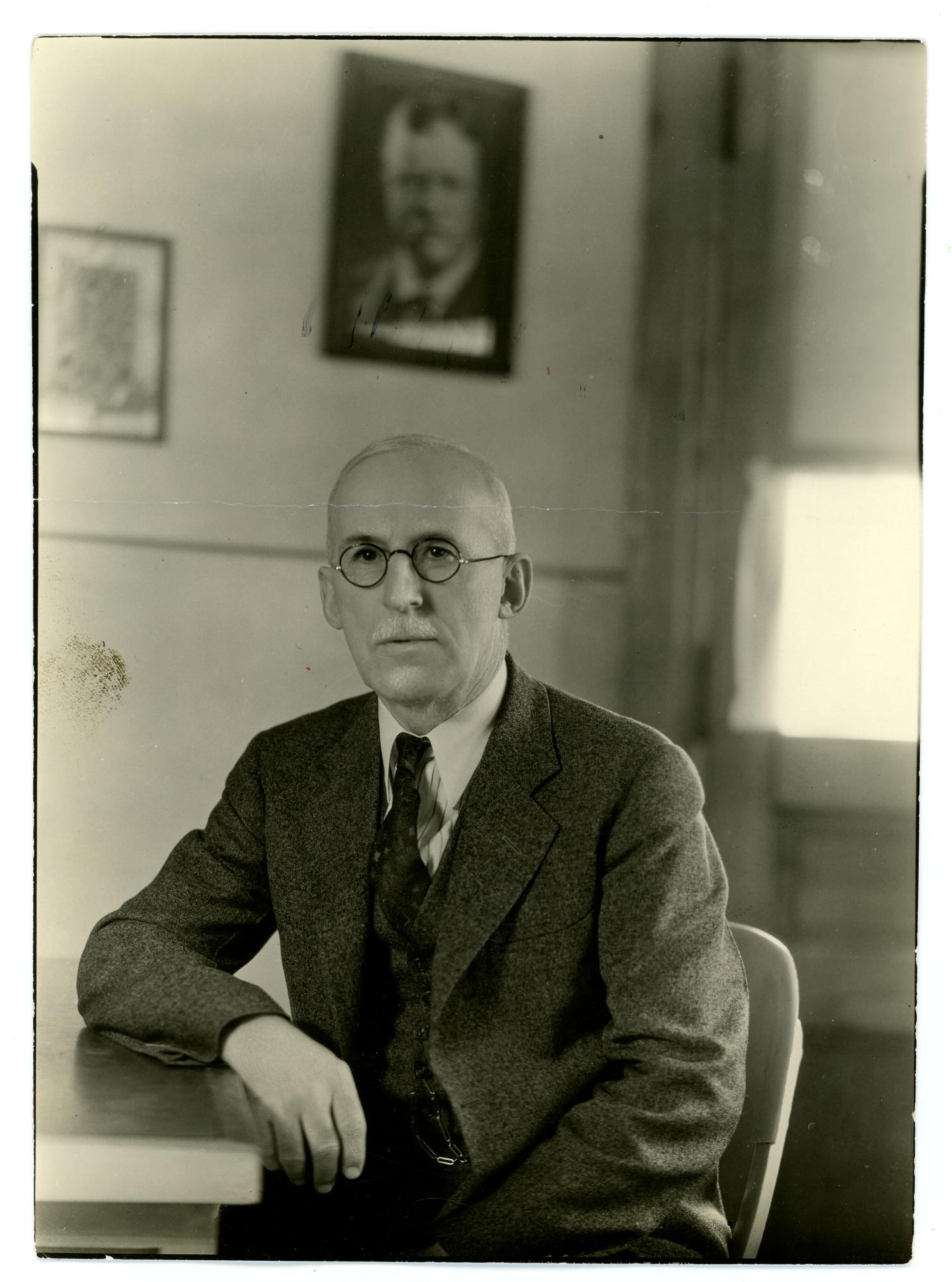

The Teachers College also began to take an active role in screening students for tubercular infections. In 1934, the college required incoming freshmen to have the Mantoux test, which indicated whether or not a student had an active infection or had had one in the past. Those who tested positive, about twenty percent of that 1934 freshman class, were referred for chest X-rays ("Twenty percent of freshmen," 1934). Dr. Frank Mead, director of the campus Health Service, said that most students who showed a positive reaction would be cleared following examination of the X-rays. Very few would need treatment. But, still, Dr. Mead's advice for those who did have tuberculosis showed that the notion of a complete cure had a ways to go.

Dr. Mead said that those students "will be advised not to tire or expose themselves in any way and to seek a suitable occupation after college." Those words likely offered little comfort to students at the Teachers College, where preparation for a career in teaching was the sole mission of the school. Few school districts would look favorably on hiring a teacher who was actively infected with tuberculosis.

Mandatory testing, or proof of previous testing, seems to have been in effect for Teachers College students by 1942. In 1944, Dr. Charles B. Lyght, director of health education for the National Tuberculosis Association, warned students to be extra vigilant against the spread of the disease so that all energy could be directed to the war effort ("National tuberculosis head," 1944). After World War II, and following the discovery that several antibiotics, including streptomycin, could effectively treat tuberculosis, news in the student newspaper about this disease persisted in just two forms: reminders about furnishing proof of tubercular testing and news notes about the annual Christmas Seals campaign ("Christmas Seals on sale Dec. 1," 1933). By the mid-1950s, even these kinds of articles had disappeared.

Today there are concerns that tuberculosis might return, at least to some extent, because the tuberculosis bacillus has developed resistance to standard treatments. But probably for most college students, tuberculosis, once a dreaded disease that affected many young people, has become a thing of the past ("T. B., once the nation's leading killer," 1991).

Smallpox

Smallpox was probably feared just as much as tuberculosis among early students of the Normal School, but treatment for smallpox, via inoculation, was considerably more advanced than it was for tuberculosis. The pioneering work of Edward Jenner in the late eighteenth century showed that inoculation with the cowpox virus gave immunity to the related, but much more serious disease, smallpox. Inoculation programs spread widely, but by no means universally, in the Western world in the nineteenth century. There was little doubt that the inoculation was effective, but it seemed as if many people did not get the inoculation until there was an outbreak of smallpox in their vicinity.

In 1882, the student newspaper reported that all Normal School students had been vaccinated, though it is not clear if the inoculation program had been associated with the school. The article also sounds the first of many recurring complaints about the severity of the reaction to the vaccination: some students required slings to support their sore arms ("Our Friend Says," 1883). In February 1901, those who lived at Sawyer's Club, an off-campus boarding house, were vaccinated after a smallpox scare ("Sawyer's Club", 1901). Nearly all of the faculty were vaccinated at the same time. In May of that year, student Joseph Johnson was diagnosed with a possible case of smallpox. While the diagnosis was less than sure, and while whatever illness he had seemed mild, the Normal School took the unusual step of constructing a small shed, or pest house, on the northwest corner of campus where he would live in quarantine until he recovered. A cousin looked after him there. Mr. Johnson apparently recovered, because in the following school years he participated in the usual round of sports and literary society activities ("Student quarantined," 1901).

Some students who left the Normal School to take teaching jobs around the state faced smallpox scares in their new locations. In 1902, for example, the Des Moines schools were closed due to smallpox. Also in 1902 George Cleveland, of the Class of 1901, had been teaching in Mt. Auburn, but was quarantined for smallpox at home in Cedar Falls. Another Normal School alumnus, Horatio B. Lizer, took Mr. Cleveland's place in Mt. Auburn until he recovered ("Alumni Columns", 1902). A similar situation took place in Pomeroy, where David Patten substituted for G. W. Randlett, after the latter's home was quarantined ("G.W. Randlett," 1902).

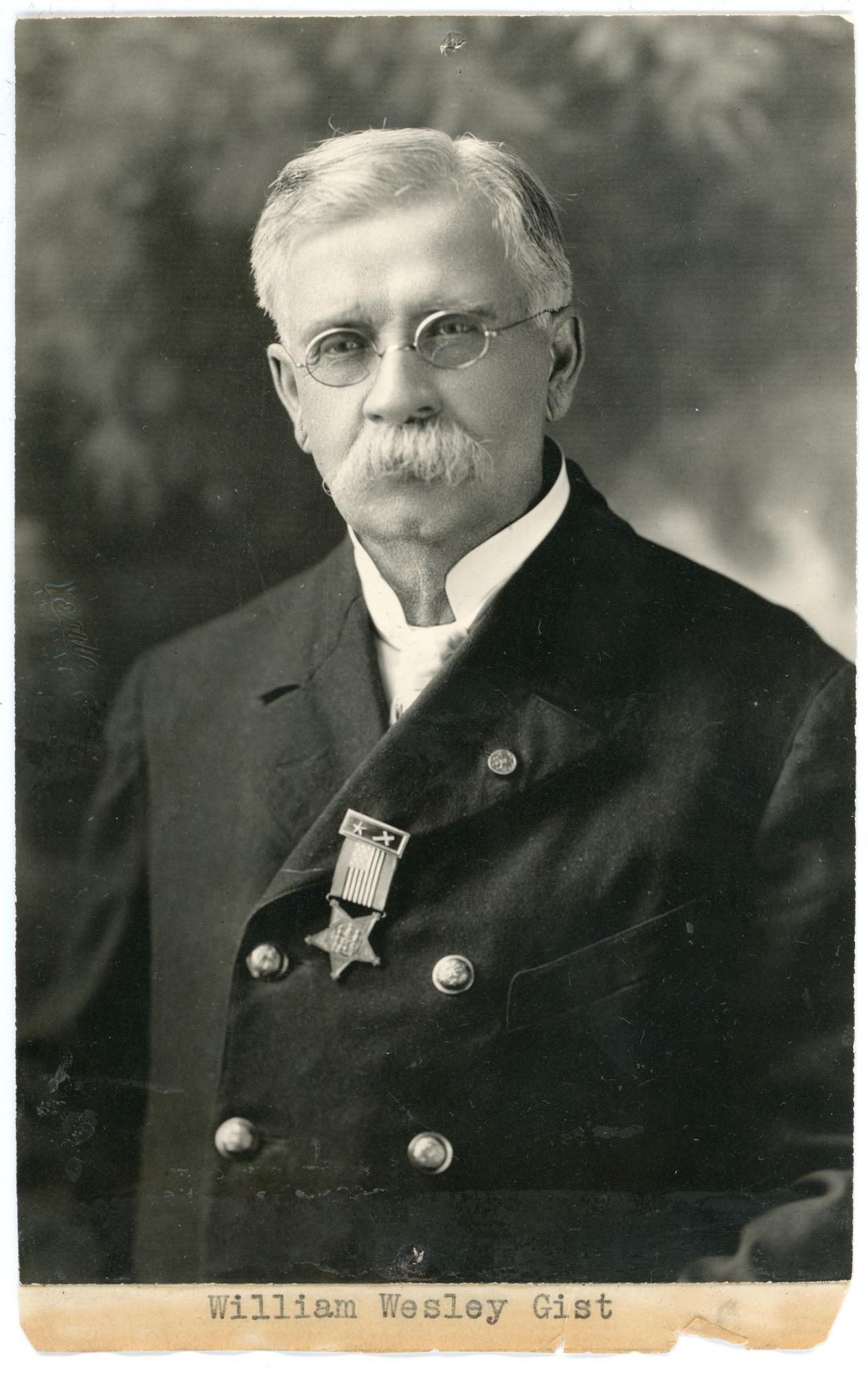

Scattered cases of smallpox, or suspected cases that resulted in quarantines near the Normal School, continued to occur. In 1905 student Etta Thomas became ill with smallpox and did not return to school ("Etta Thomas," 1905). The Cramer family of Cedar Falls was quarantined in that same year, and the next year the College Hill home of Professor William Wesley Gist, of the English faculty, was also quarantined.

Student Abigail Shumway became ill with smallpox late in the fall 1907 term and did not return to school ("Abigail Shumway," 1907). State officials were angry that people neglected to be vaccinated or sometimes vocally questioned the effectiveness of this preventive measure. Even some students at the Teachers College seemed not to take smallpox seriously (Seerley, 1910). An editorial in the student newspaper in 1911 calls upon doctors to enforce the mandatory thirty day quarantine for scarlet fever and smallpox. The editorial goes on to say:

- "But all the blame cannot be laid at the door of the physician. In many instances

the students are responsible for the spreading of the diseases. Students go to

the pest house and detention hospital and sit on the porch conversing with

patients who are still broken out with the disease. Because the disease is not

malignant, some cases are not reported, and in at least one or two, if not more

instances, students completely broken out have been found mingling with

others in the street." ("Editorial," 1911).

That kind of casual attitude, even with the mild form of smallpox going around in 1911, could have had disastrous consequences. Fortunately, it did not. Following another round of vaccinations in the spring of 1911, students Vera De Seelhorst ("Miss Vera De Seelhorst," 1911) and Kathryn Heddens ("Miss Kathryn Heddens," 1911) had reactions severe enough to send them home to recuperate.

Chapman Hall, a rooming house on College Hill, was quarantined during the spring. One resident, Mary Alice Hyde, was inspired by the experience to write a poem that was published in the 1911 yearbook, the Old Gold. She entitled her humorous work "Smallpox Nevermore", and set it to the meter of Poe's "The Raven" (Hyde, 1911). The ten stanza poem begins:

- "Once upon a evening dreary

As some maidens blithe and cheery

Sipping chocolate, eating candy,

Dreaming not of coming woe

Gayly chattered, work ignoring,

Suddenly a call imploring

Came from Freda, sick and fainting,

As she dropped upon the floor.

' 'Tis the smallpox,' someone muttered

As we hastened from the door.

Only this and nothing more. - Chapman Hall was filled with sorrow;

'Vaccination on the morrow':

Said the doctor, 'No admittance,'

And he firmly closed the door.

Anxiously next morn we waited,

Faces white and breath abated,

As we bared our arms and watched him

Carving those who'd come before.

Ah, the piteous cries and shrieking

As we hastened from the door.

'Vaccination--never more!'"

Mary Alice Hyde went on to describe the anxiety and boredom of being quarantined in Chapman Hall. The women ate, worried, and fussed at each other. But it was a false alarm. "Freda", from stanza 1, did not develop smallpox, and the quarantine was lifted. The residents were free to leave the house and return to class. Their vaccinations enabled them to say, in the concluding line of Miss Hyde's poem:

- "Microbes! Smallpox! Nevermore!

There was another outbreak of smallpox in 1914, with one student recovering well, one affected severely by the vaccination, and another home from her teaching job after a quarantine at her school ("Miss Vera De Seelhorst," 1911). The disease was quiet locally until the early 1920s when several students spent time in the College Hospital, again with a mild form. In 1925 the Teachers College vaccinated over six hundred students. The impetus for this campaign was an off-campus outbreak of the disease. Dr. Mead, the head of campus health services, was very pleased with the students' willingness to be vaccinated. He said that students could expect to have a sore arm and maybe feel a bit sick for a few days, but the discomfort would amount to nothing compared to the effects of a severe case of smallpox ("Nearly 600 vaccinated," 1925). Teachers College students were apparently spared, but the outbreak was severe enough elsewhere that basketball games against teams from Mason City and Iowa Falls were postponed ("Sport summary," 1925).

As vaccination became more universal, outbreaks and quarantines became less frequent. In the spring of 1930 two students were quarantined for smallpox in the College Hospital. Probably the last campus smallpox scare took place in 1938, when the Lambda Gamma Nu fraternity house was quarantined after one of the brothers was confined to the hospital with smallpox. There was a mild controversy about whether or not other members of the fraternity left the house just before the quarantine was imposed, even though they knew that the quarantine would very likely be put into effect. In any case, the person with smallpox recovered, the unvaccinated fraternity brothers received vaccinations, and the quarantine was lifted at the appropriate time ("'Bean' Hutchison," 1938).

While many states had nearly eliminated smallpox by the 1930s, Iowa continued to show a significant number of cases. As late as 1939, there were over one thousand cases reported in Iowa. Many new students came to campus with what health services staff considered to be inadequate immunization. Consequently, the Teachers College scheduled rounds of smallpox vaccinations at least through the early 1940s ("War on smallpox," 1940). But, after that, smallpox cases and quarantines disappeared from the college record.

Even though the salutary effects of inoculation were well known before the Iowa State Normal School was founded in 1876, outbreaks of the milder forms of smallpox plagued and frightened the campus for almost seventy years. As nearly as can be determined, no students died of the disease. However, a large number contracted the disease, were confined under quarantine, or suffered the effects of the vaccinations. What is more, fear of the more virulent form was always present.

Measles

Measles of several varieties showed up regularly among students from the earliest days of the school. Before 1900 the student newspaper reported that many students got sick enough to go home to recover from the measles. But the paper seemed to strike a casual, and even humorous, note about the disease. In the late winter of 1894, in reaction to a widespread outbreak of the disease on campus, the newspaper suggested that students really should plan to have measles before they come to college:

- "It seems some people really neglect to have their measles when they are most

becoming--say at the age of ten . . . ." ("It seems some people," 1894)

The outbreak faded in March; most students had only mild cases. But it was back again in the late winter of 1895, more widespread than the year before. That winter the student newspaper had been publishing the names of students who had the measles, but, in the February 16, 1895, issue of the Normal-Eyte, the editor said:

- Last week we published the names of those who had the measles or other

forms of sickness but now the list has become so long, that we should need

to publish a supplement to do so. We are sorry to slight those persons who

are so good catching [it], but next time perhaps so many will not try it. ("Last week," 1895)

Once again, the epidemic faded in March. A few students were sick enough to go home, but most seemed to endure it in good nature in their boarding house rooms. The campus was spared in 1896, but measles were back in early 1897, with an outbreak in Rownd Hall, a College Hill rooming house ("A very unwelcome visitor," 1897).

This time the disease seemed more severe and long-lasting; it persisted through May. A similar pattern--onset later in the school year and longer persistence into the spring--appeared in 1898, 1899, and 1900. Students followed the old curative regimen: for fear of blindness as a result of the disease, they convalesced in dark rooms and wore dark glasses once they re-emerged into the public. Measles appeared again in 1903 and then in a widespread epidemic in 1904, when residents of nearly all College Hill rooming houses were infected ("Measles, an unwelcome visitor," 1904). After several years' respite, the pattern re-emerged in 1907 and 1908. Some students got sick in the spring of 1907, but there was a major outbreak of measles, as well as other illnesses, in the spring of 1908 ("Measles, grip, tonsillitis," 1908). In the years of severe outbreaks, the disease seemed to persist until the weather warmed, people got back outside more regularly, and students started to scatter for the summer.

In the years leading up to World War I, there were a few cases of measles. But not until the spring of 1918 was there another widespread and persistent outbreak, with a number of students requiring hospital care. There were epidemics again in 1924 ("Miss Elizabeth Hart", 1924) and 1926 ("Marie Zimmer and Jessie Sutter," 1926).

There was an outbreak of measles again in the winter of 1943. This allowed for jokes about wartime sabotage in the form of "German" measles. There were enough cases-- more than twenty-five at a time when enrollment had sunk below 1000--to disrupt campus athletic and social activities. Peggy Entz was a candidate for the campus Old Gold Beauty contest in 1943. Those who were selected as Beauties had full page portraits in the student yearbook, the Old Gold. Winners of the contest were announced at the Old Gold Beauty dance. However, Peggy Entz was unable to attend the dance because she had the measles. So she learned of her selection over the radio ("Sabotage! German measles epidemic," 1943). The last significant outbreak of measles occurred in January and February of 1952 ("Measles epidemic," 1952). This epidemic, confined almost exclusively to women who lived in Bartlett Hall, was short-lived. The Health Service Director declared it over by mid-February ("Epidemic is over," 1952).

For the next thirty years, little or nothing was heard on campus about measles until a measles vaccination became available. The UNI Health Center offered free vaccinations in 1983 and in following years (Harkin, 1983). By 1991, the university took the step of requiring all students to furnish proof of having been vaccinated against measles (Hoelscher, 1991). The deadline for furnishing that proof was set at November 1, 1992. Those who did not furnish proof would not be allowed to register for classes. Meeting that deadline proved difficult; about half of the students had not provided proof by October 1992 (Craig, 1992). Consequently, the deadline was extended to May 7, 1993, and students were allowed to register for the Spring 1993 semester (Romanin, 1992). Even with that extension, compliance was nowhere near complete, with hundreds of students still not furnishing proof of vaccination. Over the next several years, the university developed a combined program of notifications, clinics, and public reminders to gather the required proof from each student. The university also began to exert its authority to withhold permission to register if that proof did not appear.

Over the years, measles seems to have been more an annoyance and an inconvenience than a serious disease on the UNI campus. For many years it appeared as a regular visitor in the late winter and early spring. Now, however, if students keep their vaccinations up to date, measles is likely a thing of the past.

Mumps

Mumps has followed a course on the UNI campus similar to that of measles. There were recurrent epidemics up until about 1940. After that, not much was heard about it until vaccines became available in recent years. The casual, mildly sympathetic attitude shown on campus toward mumps resembles the attitude taken toward measles. That attitude resulted in many comments about "cheekiness" or "having cheek".

There were outbreaks of mumps in the spring and fall of 1894, the winter of 1895, and the spring of 1896. Several of these outbreaks were coincident with measles outbreaks, but they were not as widespread or persistent as the measles. There were occasional cases reported over the next few years, but the next serious outbreak occurred in 1910, when quite a few students fell ill. Treatment seems to have been rest, preferably at home.

In the next few years there were a few cases of mumps, some resulting in hospital stays, but this may have been due more to having a hospital available on campus than to an increase in the severity of the disease. Cases of mumps rose sharply again in 1918, with at least twenty-three cases reported among students in the Teachers College High School, then located on campus in what is now known as Sabin Hall and many more cases among the college students ("Training School," 1928). There were a few cases in the middle 1920s, but probably the last significant outbreak occurred in the spring of 1929. That outbreak seemed to have been concentrated in off-campus fraternity houses. One student, Mary Ella Jones, came down with mumps in 1941.

As a consequence, she missed the opportunity to see her own one-act play produced and to act in another play written by Mona Van Duyn ("Current student productions," 1941). There were occasional cases reported after that, including one as late as 2006 (Jenkins, 2006), but with the availability of a combined measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and its booster, mumps is now a rarity on campus.

Polio

Polio seems to have made only a mild impact on students at the Iowa State Normal School during the school's early days. This may have been due to the age at which people contracted the disease in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At that time most cases of polio appeared among young children: hence, the alternate name for polio, infantile paralysis. Young children caught it and then recovered, or were killed or debilitated by it before they reached college age. The age of onset advanced during the twentieth century, but even by 1950, two-thirds of the cases occurred in children under the age of fifteen. It was, nonetheless, a disease that was on the minds of Teachers College students. In 1934, students organized a dance in honor of President Franklin Roosevelt, who contracted polio at the age of thirty-nine. Proceeds from that dance went to the Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, founded by the President. About three hundred couples attended the dance, which was coordinated with thousands of similar dances around the country ("Ball for President," 1934).

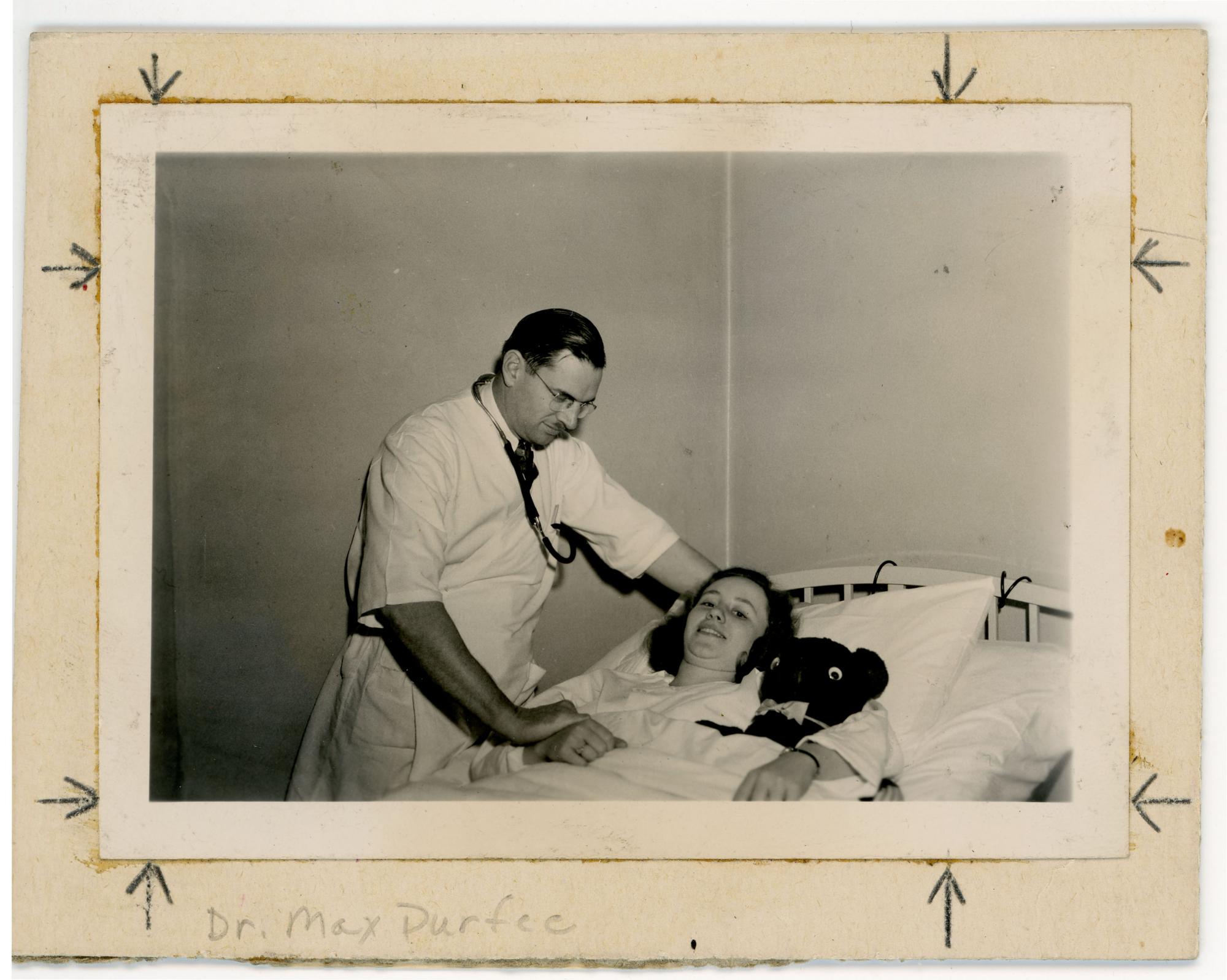

Dr. Max Durfee, of the college Health Service, said in 1940 that knowledge about polio was incomplete. He understood that it was a viral disease, but could describe prevention in only the broadest terms: he urged students to stay in good health and to avoid people who had the disease ("Little is known about paralysis," 1940). Following World War II, reported cases of polio grew at a frightening rate around the country. In the fall of 1946 a Teachers College freshman contracted what was described as a mild case of polio. Symptoms became apparent on October 7. She was taken to the University of Iowa Hospital, where she underwent treatment until November 23 ("Mild case of polio," 1946). After making good progress, she went home to recover more fully. She was pleased with her progress, but she was unable to return to school that fall. Those with whom she had been most closely associated on campus were monitored for polio, but no one else developed the disease ("Polio victim recovers," 1946).

In 1951, as coverage of the national polio epidemic enhanced general awareness about the disease, Dean of Students Paul Bender asked the student government to sponsor a fund drive to raise money for research on the disease. Members of the campus service fraternity, Alpha Phi Omega, handled the details ("Bender requests," 1951).

The disease hit close to home soon afterward. In October 1952, Ned Wall, a June 1952 graduate, died of polio at an army training camp. He was twenty-two years old and engaged to be married to another Teachers College student ("Spring graduate victim," 1952). However, the lasting effects of the disease varied. In 1954 a Teachers College alumna living in the Chicago area reported that her family had had polio, but that everyone, including two children, survived without paralysis ("Werts hit by polio," 1954).

In 1955 a writer in the student newspaper offered a grim description of the life of those who had suffered a severe attack of polio and then needed to rely on an "iron lung" to breathe:

- "The hall is dark and foreboding. Life is run by a machine . . . One click . . .

One breath . . . Yet the machines drone with their monotonous kathunk . . .

kathunk . . . kathunk. The human bodies in those machines live, breathe,

speak, and move by that ceaseless rhythm; even as death walks these

dismal halls . . . - As death strides the halls enjoying his own symphony you see with him

another figure. Evidently a friend. The other figure is horribly twisted

and deformed, he is a grotesque cripple. He is the ruler of the living

dead. He is POLIO . . . ." (Baldwin, 1955).

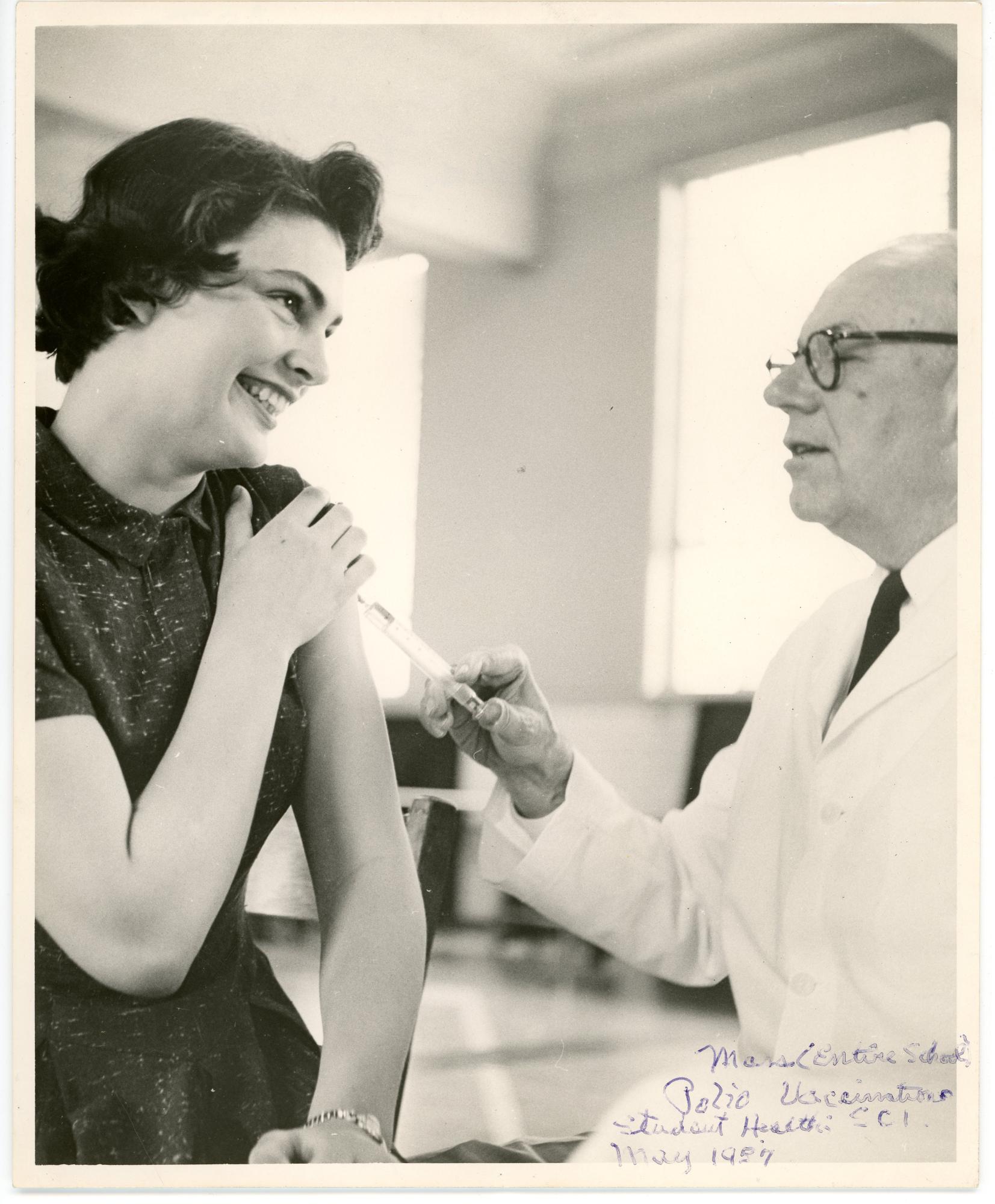

But relief was in sight for those who had not yet contracted the disease. In April 1955 came the announcement of the Salk polio vaccine. It is hard now, in retrospect, to describe the relief that this announcement created across the nation, especially among the growing postwar families with small children. The grim killer and crippler of young people had met its match. In February 1957, the head of campus Health Services, Dr. French, announced that the college would offer a series of three polio shots that would be available to all students and their families. One shot would be given in March, one in April, and the third in the fall of 1957 ("Shots for polio," 1957). The shots would cost $1 each ("Correction," 1957). Dr. French urged everyone to register for the shots. Due to a shortage of vaccine, the initial shot was delayed ("Notice," 1957), but, when the vaccine did arrive, 1,624 students and student family members received the first shot. The student newspaper claimed that this was the first mass polio vaccination at an Iowa college ("Vaccinations to be given," 1957).

The second shot was administered on May 23, 1957, with the third shot given in March 1958 ("Third polio shot," 1958). Because the three shot series did not provide 100% protection against polio, a booster shot was available later in 1958 ("Flu expected, shots available," 1958).

Thereafter, the Health Center had the vaccine on hand for those who needed it. And, beginning at least by 1964, the Health Center had the oral trivalent vaccine. This vaccine combined the effect of the earlier three shot series in one oral dose ("Polio vaccine now available," 1964).

So, the experience of polio on the University of Northern Iowa campus was relatively limited, first, because the disease tended to affect young children before they reached college age; and, second, due to the discovery of a powerful vaccine.

Influenza and La Grippe

The word influenza appears in campus publications as early as January 1896 when the student newspaper reported:

- "Many of the students have met with the influenza and also have absented themselves from school of a few days in order to properly entertain the guest. May he soon depart to regions where he will be better appreciated." ("Many of the students," 1896).

That, apparently, was an isolated use of the word. It does not appear again in student publications until 1915. However, that does not mean that influenza disappeared for twenty years. Rather, people tended to use an old-fashioned term, la grippe (or grippe or grip), when referring to acute, sometimes febrile illnesses, usually accompanied by upper respiratory distress. As used in campus publications, la grippe probably encompassed illnesses such as severe colds, bad coughs, tonsillitis, and influenza.

Whatever the exact nature of la grippe, it was a common diagnosis among Normal School students and other members of the campus community. There was a major outbreak in the winter of 1897 that affected both students and faculty ("Notes and comments", 1897). Student Wesley Wiler lost his voice and could not attend class ("Wesley Wiler," 1897). The staff of the student newspaper, the Normal-Eyte, had the grippe and barely got the paper out. They joked that the Personals column, which featured news notes about the campus, should better be called the Sick List ("The Normal Eyte staff," 1897). Faculty members Myra Call ("Miss Call's name," 1897) and William Dinwiddie ("Local and personal.," 1897) also missed classes due to the grippe.

The Grippe

The outbreak of grippe in the winter of 1899 was much more widespread. It had apparently started before Christmas 1898. In the first issue of the Normal-Eyte for the new year, the staff posed the question and offered advice:

- "Have you had the Grippe? If you haven't, 1st, be careful, 2nd, be careful. If you have, just keep on being careful." ("Have you had the grippe?," 1899)

For weeks during that winter the news note sections were once again a sick list. President Seerley's wife, Clara, had a bad case of the grippe ("Mrs. Seerley," 1899). Professor Wright and his daughter were ill ("Prof. Wright," 1899). When Professor Page missed several days of class, the newspaper felt obliged to say that, yes, Professor Page had been ill, but, no, it was not due to the grippe ("Mr. Page", 1899). Another article simply listed fifteen names of students who had the grippe ("The following are a few", 1899). Unfortunately, none of the articles reports symptoms. They simply state that people felt sick enough to miss a few days or a week of school. The worst of the epidemic seemed to be over by mid-February. In assessing the work of the winter term, President Seerley wrote:

- "Outside of much interference with work that has been caused by the great amount of temporary illness of students, the term has been a good one. Probably at no past term has this temporary illness been so extensive." (Seerley, 1899)

The next major outbreak began in December 1900, peaked in January 1901 ("Dr. Hillis postpones," 1901), and continued well into the spring. There were scattered cases in the following years, but another epidemic arose in 1908. It peaked in January 1908, accompanied by other illnesses. It was extensive enough that the student newspaper omitted its news notes section, and, instead, printed the following:

1911 was another bad year for the grippe. Many students missed school. At least one student left school due to the severity of the illness. The grippe also affected members of the faculty and their families: both Mrs. Seerley ("Mrs. Homer H. Seerley," 1911) and Mrs. Wright ("Mrs. D. S. Wright," 1911) were again "confined to their rooms" with the illness. Another round of the grippe struck in 1913. This outbreak seemed to be particularly hard on the faculty, with Professors Coffey ("Prof. Roy V. Coffey", 1913), Condit ("Prof. Condit," 1913), and Merrill missing class for a few days ("Prof. Merrill," 1913).

At about this time, the word grippe was replaced with the word influenza. Grippe appears as late as 1921 ("Miss Irene Stevens," 1921), but influenza became the common and dominant term beginning in 1918 ("The sad news," 1918). In one of the last references to the grippe, the student newspaper does note the symptoms:

- sore throats;

- aching joints;

- raspy voice ("La grippe," 1915).

Occasionally the grippe had been so severe that some students missed many days of class or even withdrew from school. And there had been the unfortunate case of Charles Babcock who died of "complications of the grippe" back in 1902. Mr. Babcock had graduated from the Normal School in 1899 and was teaching in South Dakota. He had contracted the illness after leaving the Normal School, but the lesson remained for students and faculty: grippe could be serious and even deadly ("On the morning," 1902).

Still, nothing could prepare the Teachers College community, or the world, for the effects of what was to begin in 1918. The exact geographic location of the origin of what was known as Spanish influenza is controversial--possibly the Far East, possibly Europe, or possibly even Kansas. The disease was observed in Kansas in March 1918 and seemed to be the normal seasonal virus. But by the time that students returned to the Teachers College campus in September 1918, a second, more deadly mutation of the disease was waiting. Onset at that time of year was unusual; typically the flu was most active in January and February. Something else was unusual, too: while typical influenza outbreaks had greater effects on young children, the sick, and the elderly, this mutation strongly affected young, healthy people, such as soldiers and college students. If the disease itself was not fatal, then it could leave people weakened to the extent that pneumonia would finish the job. Professor David Sands Wright, of the Religious Education faculty, notes in his diary:

- "A disease cald [sic] Spanish Influenza is sweeping the country from the

lakes to the gulf. It first appeared in the various cantonments whence

it has spread rapidly in all directions. It is unlike La Grippe in that it attacks

the lungs, causing great pain and weakness, with a tendency to take the

form of pneumonia with fatal results. The number of cases in the

cantonments is counted by the thousands and the deaths are many.

Its [illegible word] has temporarily stopped the sending of American

soldiers to France. Nearly 9 hundred cases have been reported in

Cedar Falls." (Wright, 1918)

Troop movements and global transportation associated with World War I probably helped the disease to spread rapidly. Mortality rates were at least fifty times greater than those associated with previous influenza epidemics.

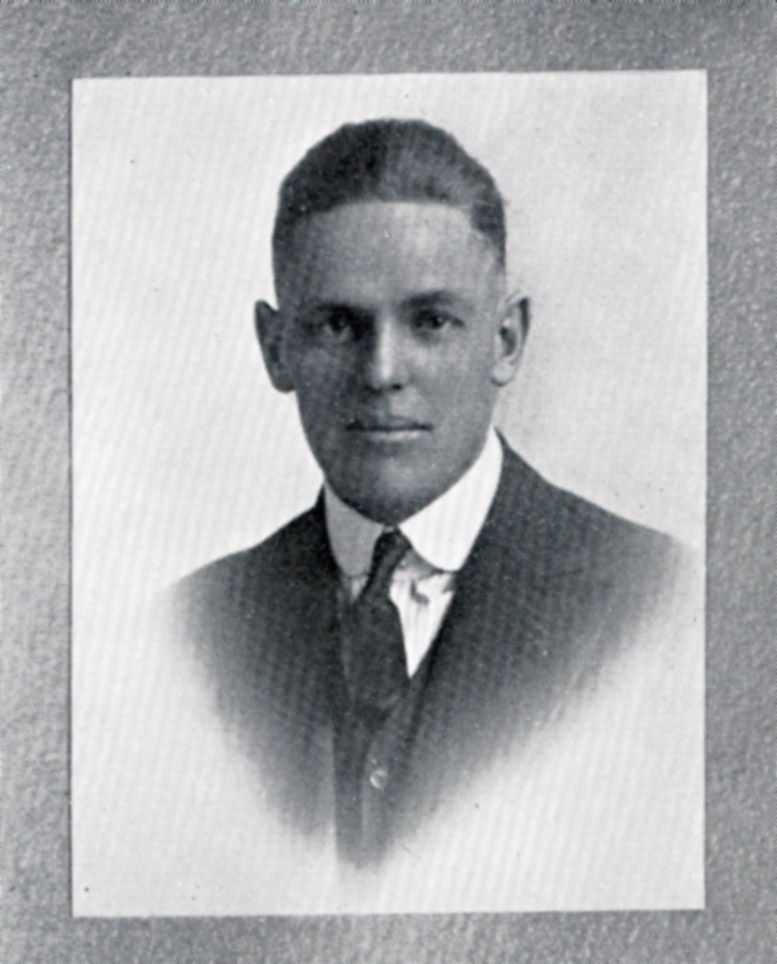

On September 30, 1918, the flu took its first Teachers College student: Ina Rue, a sophomore, died after a week with the flu. She was eighteen years old ("Ina Rue passes away," 1918). President Seerley reported that there were at least one hundred students sick with the flu, some critical, as of October 1, 1918. News followed shortly thereafter of the death of Axel Justesen, a well-known and popular former student, who had been editor of the student newspaper. He died in early October at a US Navy camp in New York ("The sad news," 1918).

Professor David Sands Wright offered a sad tribute in his diary entry of October 11, 1918:

- "The College is saddened today to learn the news of the death of Axel Justesen. He graduated in the Class of 1916, and was its most prominent if not the strongest member of his class. A son of poverty, he worked his way thru school by the labor of his hands taking any work he could find to do. He assumed the editorship of the College Eye for the last part of his course. He died in a hospital in a cantonment in New York of the fatal influenza which is

terminating the careers of so many soldiers and citizens." (Wright, 1918)

October 1918 could possibly have been the most disrupted and confused month in the history of the school. The war had sharply reduced enrollment, especially of men. A number of faculty had left campus for war service of one sort or another. There was a military training unit, the Student Army Training Corps, headquartered in what had been the Gymnasium (now the Innovative Teaching and Technology Center). Food and fuel supplies were tight, and, when they could be purchased, they were expensive. On top of that, there was a deadly disease on campus.

Some schools in the area, including Cedar Falls and Waterloo schools and the University of Iowa, closed for several weeks during the September and October crisis. The Teachers College, however, did not suspend classes, though other activities, including athletics, meetings, and social gatherings, were limited or canceled. The student newspaper did not begin publishing until October 15, because both the editor and the business manager were in military service ("Spanish 'flu' decreases," 1918).

By mid-October the college reported that the number of flu cases seemed to be declining. College health officials told those who thought that they had the flu to report to the Head Nurse. If a student seemed very ill, he would be admitted to one of the college hospital facilities. If a student were not particularly ill, he would be told to isolate himself and to stay in bed. Health officials believed that flu cases were made worse by exertion of any sort. Students who missed school would have the opportunity to make up their work when they recovered. College authorities believed that their program of care was helping to stem the epidemic ("Unnecessary activities banned," 1918).

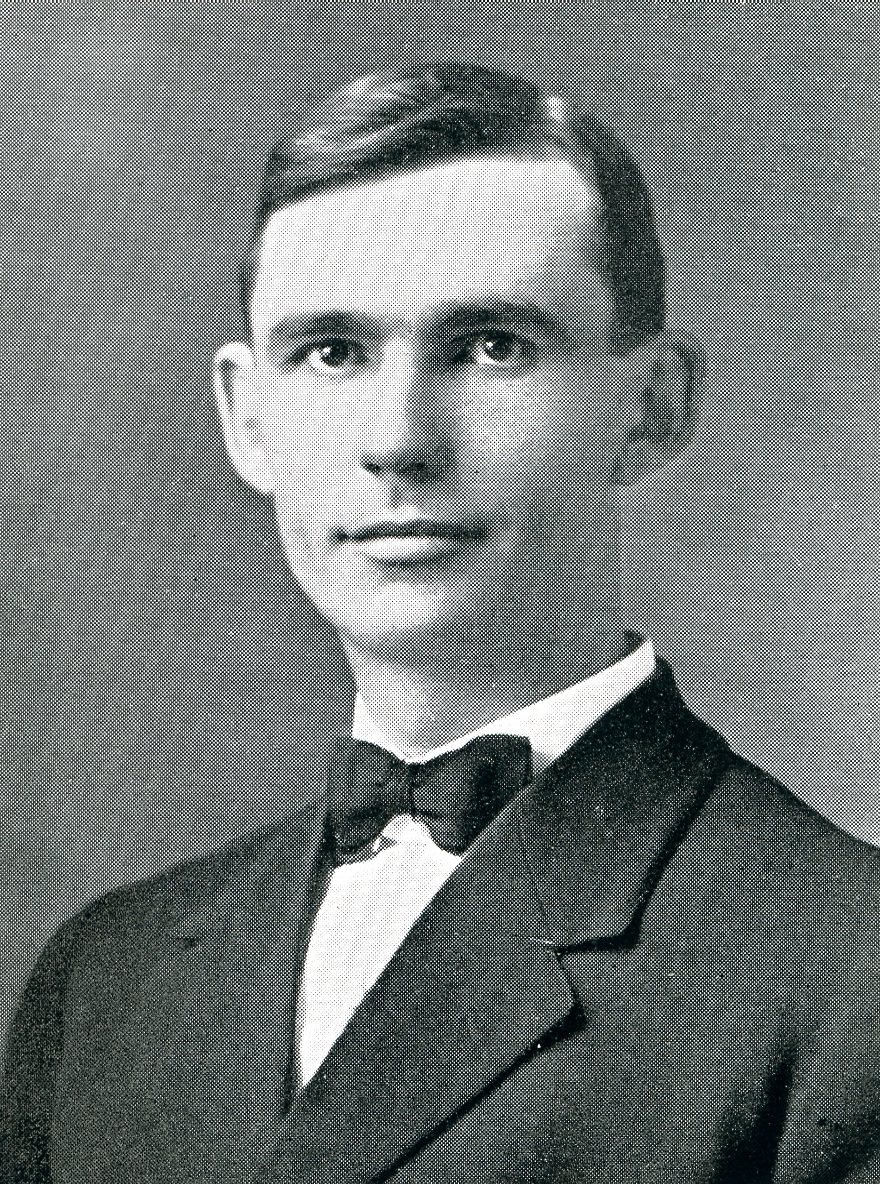

On October 29, President Seerley stated that the danger point of the epidemic had passed. To some extent, he was correct. The sheer numbers of active cases on campus did decline, though at least some students and several faculty members, including Professors Fagan ("Professor Fagan", 1918), Underwood ("Professor Underwood," 1919), and Dougherty (Miss Mary Dougherty," 1918), came down with the flu in November and the following months. Mabel Clayre Harkin, an assistant teacher in the Training School, went home in January 1919 to care for her father, who was critically ill. She herself contracted influenza and died before the end of the month ("Mabel Clayre Harkin," 1919). Professor Reuben McKitrick, of the Economics faculty, was also hit particularly hard by the flu. He was granted sick leave for the spring term of 1919, but his health failed to improve. He died on May 29, 1919 ("Professor Reuben McKitrick," 1919). Professor Wright notes in his diary entry for that day:

- "At noon today occurred the death of Professor McKitrick. He died suddenly of a

tubercular trouble for which the hope of a cure was held until quite recently . . .

He leaves a wife and four little children . . . " (Wright, 1919).

Probably the most shocking effect of the 1918 epidemic was the number of deaths reported in the broader Teachers College community. The alumni newsletter and the student newspaper continued to report dozens of deaths, due to influenza and its complications, typically pneumonia, for months after the epidemic wound down. Nearly all of those deaths were among people who had graduated from the Teachers College within the previous few years. They were in their twenties and thirties, just beginning their careers or families. Many, many families lost a young person during the 1918 influenza epidemic.

The flu returned in the winter of 1919-1920. It was widespread, but not as severe as the flu of 1918-1919. The January 28, 1920, issue of the student newspaper reported at least fifteen new cases, but it also noted that quite a few students had been released from the hospital and were recovering well ("Miss Hazel Cole," 1920). Even so, sad reports continued to come in: former students Rachel Patten ("Rachel Patten", 1920) and John Howard Rich ("City mourns death," 1920) died of complications of influenza in February 1920.

There were smaller outbreaks of the flu during the 1920s, with 1926 probably the worst. One student, Altha Hinckle ("Altha Hinckle," 1926), was in the hospital for ten days, and, at one point, at least four faculty members were unable to meet their classes. The 1928 flu season began early enough to weaken the basketball team in its initial matches ("Tutor cagers play," 1928). The student newspaper hoped that everyone would come back to school after Christmas vacation completely cured.

The 1932 season was difficult, too. A number of students were quite ill, and President Latham was away from his duties for ten days due to influenza ("President resumes duties," 1932). The most serious case was Professor Warren L. Wallace, of the Social Science faculty. He had been ill with influenza for six weeks when the newspaper reported, on March 18, 1932, that he expected to return to work within a week ("W.L. Wallace," 1932). That, however, did not happen ("Professor Wallace," 1932). Professor Wallace died on May 10, 1932 ("W.L. Wallace burial," 1932).

The later 1930s and early 1940s seemed to have been quiet as far as influenza is concerned. In January 1941, for example, the Director of the Health Center said that no cases of true influenza had been reported so far that school year ("Follow directions," 1941). But the illness came back in strength in the middle and late 1940s. There were enough cases in the fall of 1945 that officials had to deny a rumor that the school would close early for Christmas vacation. They told students who were ill to stay in bed and to avoid contact with others until they felt better ("School stays open," 1945).

Flu shots were available to Teachers College students at least as early as the fall of 1946, but apparently few took advantage of this preventive measure ("Flu, cold "shots" ready," 1946). Students with the flu occupied all hospital beds on campus in the winter of 1947. As other students came down with the illness, they were told to stay in bed in their own rooms, where a nurse would check on them regularly ("Flu cases," 1946). The college promoted its program of flu shots in the coming years and offered the following advice to avoid contracting the illness:

- study early and avoid late hours;

- do not become over-heated;

- stay away from windows at night;

- eat all three meals;

- avoid crowds (""Flu" shots offered," 1948).

To a considerable extent, that advice had not advanced much over the previous fifty years. The next big outbreak was in 1953, when, once again, the hospital beds were full and some students were isolated in a special ward in Bartlett Hall. Another ward was available for men in Baker Hall ("Influenza causes hospital overflow," 1953).

The 1957 outbreak had a significant and memorable impact on campus life, because it affected so many people simultaneously and because it reached its peak at an unfortunate time. The 1957 outbreak started early in the school year. By October at least five hundred cases had been reported on campus, with three hundred of those cases having been reported between October 13 and 18. The 1957 flu strain did not seem to be especially severe, but it was very widespread. Campus health facilities were overwhelmed. It was difficult to hire additional medical staff, because just about all health care professionals either had the flu or were attending others who had it. The hospital beds were full. Special wards were full. Some students were being cared for in their rooms. Some students were sent home for care ("Total cases reach 500," 1957). Campus health officials listed the symptoms:

- Headache

- Backache

- General ache-all-over feeling

- Ringing in ears

- Sore throat

For those who had not yet had the flu, the doctors advised:

- Get plenty of sleep

- Avoid skipping meals

- Stay away from gatherings

- Avoid leaving the campus

For those who had the flu or were recovering from it, the doctors advised:

- Report your case to the dorm director or the health center

- Stay in bed; rest is vital

- Drink plenty of fluids

- Don't go to the health center unless unusually ill

- Discourage visits by unaffected students

- Once you feel well, do not over-exert or become tired ("Official Suggestions," 1957).

Dr. V. D. French gave an informative perspective in the student newspaper on October 18, 1957. Dr. French had been through the difficult 1918 epidemic. He himself was sick for three weeks during the early, less severe wave in the spring of 1918. He believed that the 1957 flu strain would be less potent that the 1918 strain, but that at least twenty per cent of Teachers College students would contract it (Fromm, 1959).

Student Jan Kimmel joined students from earlier in the institution's history by writing a humorous poem about how she felt.

- The Bug

One night while TC students

Were lying very still

An Oriental stranger

Came sneaking up the Hill. - She wandered all through Bartlett

And passing through the Links

Marched down the halls of Lawther

And gave the sophs a jinx. - And then she flew through Stadium

(They simply could not shake her)

Then at last before she passed

She ran through Seerley-Baker. - Next morning I awoke

With a throbbing in my head

My throat was sore, my back was sore

I wished that I were dead. - Yes, the Bug had been at U. and State

And now was at TC.

The Bug had come to Barlett

And the Bug had come to me. (Kimmel, 1957)

In those days, both Baker Hall and Stadium Hall served as dormitories.

Since this strain of influenza did not seem life-threatening, the big question for many students was: how will the flu affect Homecoming activities? There were strong opinions on both sides of the issue. Some believed that any kind of epidemic should be taken seriously; if crowded activities enhanced the spread of the flu, then those activities should be canceled. Others thought that the flu was really not terribly serious and that Homecoming should go on as planned. President Maucker chose a middle course. He stated that the numbers of students who had the flu remained high; one student had even developed pneumonia. Consequently, he canceled or postponed the fraternity sing, the variety show, the parade, the pep rallies, and the cut day. The football game, the faculty recital, and the Homecoming play would go on as scheduled. Students protested. They marched around campus for several hours, destroyed property, and broke into the women's dormitory. The President met with about five hundred students the next evening and again explained the basis of his decision. He pleaded with students to remain calm and to be considerate of those who were ill or who would become ill ("Events revised," 1957).

President Maucker did calm the situation, at least to the extent that students stopped their rowdy protests. The reduced schedule of Homecoming activities went on as planned. However, to this day, some alumni still have unhappy memories about the whole 1957 Homecoming situation.

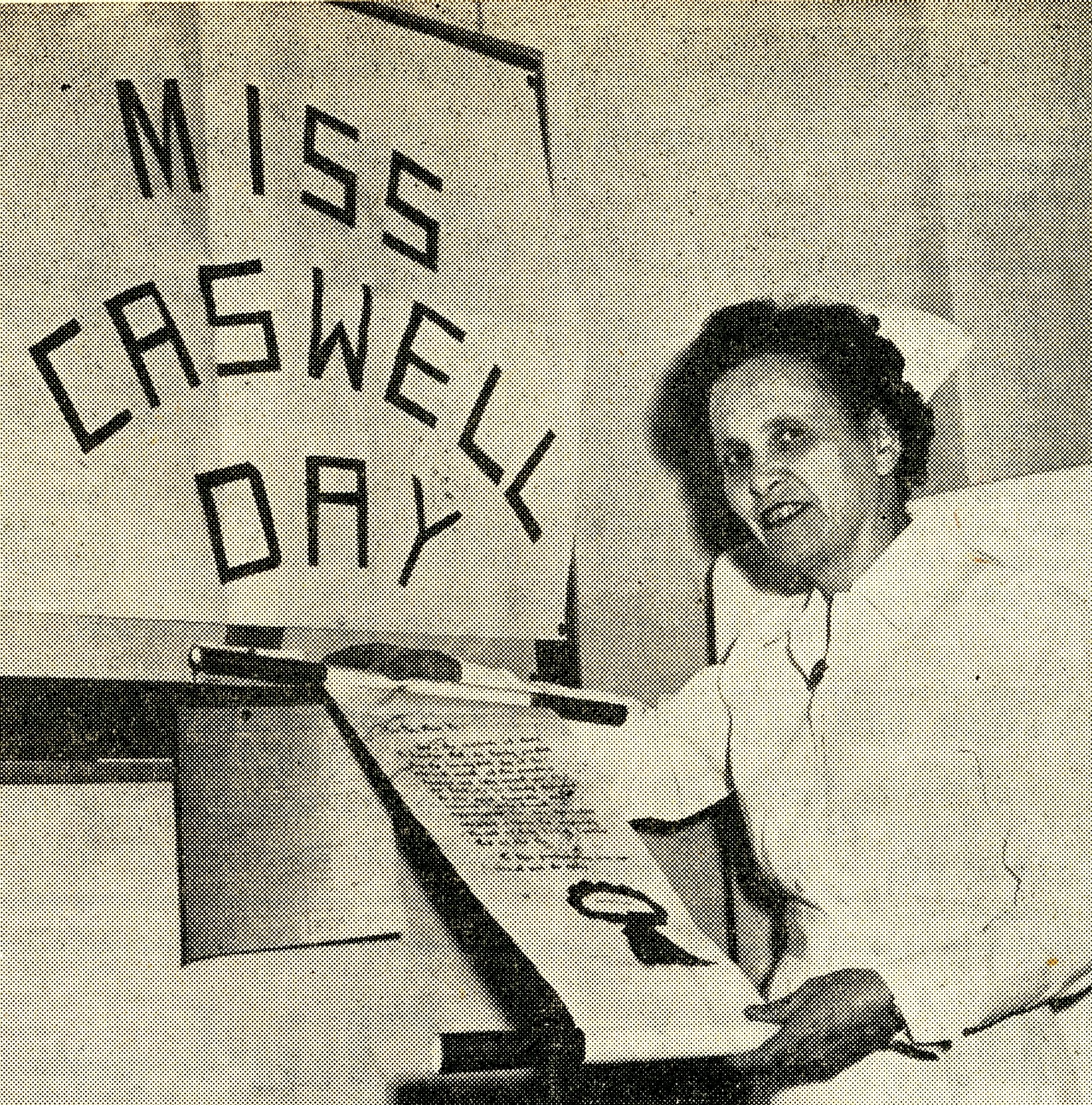

At one point during the 1957 epidemic about seven hundred students, about thirty per cent of the campus, were sick ("Flu cuts back Homecoming," 1957). In December of that year, once the epidemic had passed, the residents of Lawther Hall honored Lucille Caswell, a nurse who had cared for over two hundred patients during the epidemic.

There were no major flu outbreaks on campus over the next few years. Campus officials continued to make flu shots available and to encourage students to get their shots.

The Health Center did see some flu activity in January 1968, with about a dozen cases ("Health Center busy," 1968). There was more the following school year during the 1968 Flu Pandemic. In anticipation of that virus, the school made the flu shot available to students in the fall of 1968 ("'Hong Kong' vaccine ordered," 1968). Just a few years later, in 1976, over five thousand people lined up for shots that would ward off what was then called swine flu ("Swine flu vaccines", 1976).

There was a mild outbreak in January 1978, when the Health Center was seeing three to five times more flu patients than usual. Health Center Director Dr. Kenneth Caldwell said that this strain of flu was relatively mild: few students needed to miss class for more than a day (Krebs, 1978). A similar, though more widespread outbreak occurred the next year, when the Health Center was seeing a hundred patients a day with cold and flu symptoms. Dormitory staff noticed that the flu seemed to be moving though some of the residence halls floor by floor, with many students ill at the same time ("Outbreak of influenza," 1979). During another outbreak in 1981, a Health Center nurse offered advice quite similar to that given to students for almost a hundred years:

- Get plenty of rest

- Drink plenty of fluids

- Avoid crowds (Maltby, 1981)

During that 1981 outbreak, Northern Iowan columnist Robert Berry wrote about his experiences with the flu in an article he entitled: "Everything is wrong about being sick." He even gave the illness a name: U-flu. He described the symptoms as:

- "A kind of woozy buzz in your head, nausea, congestion, headaches, sneezing, vomiting, etc. . . ." (Berry, 1981).

He blamed it on conditions brought on by poor food, poor sleep habits, worry, and inadequate protection against the cold. Another outbreak occurred in 1988-1989.

The outbreak seemed to peak in February, with some faculty members noticing a sharp drop in class attendance (Hagerman, 1989). The university continued its flu shot program publicity campaign, and quite a few students and faculty responded (Lovelace, 1998). Still, there were at least minor outbreaks most years with the influenza B virus showing up especially in 2002 and 2003 (Pierce, 2003). Health Center officials repeated their advice about prevention--get flu shots, wash hands, and avoid contact--and remedies--drink fluids and get rest. In many years there seemed to be flurries of articles about the availability and quality of the shots--would there be enough for those who needed them and would they be on target for the particular viral mutation of that season (Kelly, 2004)?

The university is currently preparing for a potential outbreak of the H1N1 influenza, which has been predicted over the last few months. This virus is similar to, though certainly not exactly the same as, the killer influenza virus of 1918. But, like the 1918 virus, this virus may have particular consequences for young adults. The university administration has prepared emergency plans for continued operations, should an outbreak become serious and widespread. Faculty are being urged to allow students to make up work, should they miss class due to illness. Students are receiving instructions on how to avoid the flu, and, should they contract it, how to care for themselves.

By September 2009, the university had quickly distributed its limited supply of two thousand inoculations for seasonal influenza, which, unlike earlier programs, were available only to students, and not to faculty and staff.

An inoculation aimed specifically at the H1N1 virus was scheduled to be available in October 2009 (Schreck, 2009a). Cases of H1N1 influenza were reported around the country, with several deaths blamed on its effects. In September 2009, one UNI student was reported to have had the H1N1 influenza, but his case was reported to have been mild. On December 11, 2009, the Health Center made 1500 additional doses of H1N! vaccine available to students, staff, and faculty who were under the age of 25 or who had chronic health conditions (Schreck, 2009b).

At the time of this writing, the effects of the H1N1 influenza on the University of Northern Iowa community remain to be seen. However, this time, as opposed to the unprecedented outbreak of 1918, both the medical profession and campus officials have significantly greater knowledge about influenza and have also had time to prepare for it.

Summary

During its 133 year history, the University of Northern Iowa community has dealt with the major health problems faced by the broader community. These problems have ranged from illnesses that were simply inconvenient and annoying to diseases that caused death. In the early years, students who were ill needed to rely largely on their own resources. They might have been able to call upon classmates or landladies to bring them food and to take care of their basic needs. But if they needed much more than that, they usually went home to their families for care.

By about 1910, the school began to take a more active role in student health by:

- hiring health care staff;

- building a campus hospital;

- and developing a modern dormitory system.

The school's response to the influenza outbreak of 1918 showed the wisdom of this course of action. The Teachers College, despite losing a number of students, alumni, and faculty, fared better than many other institutions in the face of this killer virus. Satisfaction with this response to the 1918 pandemic likely led to the establishment and development of a permanent, organized campus health services unit. That unit has seen students through smallpox, tuberculosis, chicken pox, measles, mumps, polio, influenza, and a dozen other threats to health for almost one hundred years. Most of these diseases and illnesses, at least in so far as they appeared in severe and widespread epidemics, are now gone, thanks to inoculations, antibiotics, and better education. But there will always be threats, such as the current concern about the H1N1 influenza virus, to keep campus health officials on the alert.

- Sources Cited

- “Abigail Shumway,” Normal Eyte, December 11, 1907, Vol. 18, No. 12, p. 192, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Altha Hinckle," College Eye, May 5, 1926, Vol. 17, No. 4, p. 5, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Alumni Columns,” Normal Eyte, March 15, 1902, Vol. 12, No. 21, p. 328, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Alumni Department," Normal Eyte, February 6, 1907, Vol. 17, No. 19, p. 299, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Alumni Department,” Normal Eyte, January 10, 1906, Vol. 16, No. 15, p. 235, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Ana Wormhoudt,” Normal Eyte, April 9, 1904, Vol. 14, No. 28, p. 444, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Ana Wormhoudt," Normal Eyte, February 6, 1907, Vol. 17, No. 19, p. 299, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “A very unwelcome visitor,” Normal Eyte, January 30, 1897, Vol. 6, No. 17, p. 201, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Baldwin, Claire. "The Living Dead," College Eye, January 21, 1955, Vol. 46, No. 16, p. 2, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa,

- “Ball for President attracts many to Commons Tuesday,” College Eye, February 2, 1934, Vo. 25, No. 29, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “‘Bean’ Hutchison says rumor isn't so,” College Eye, February 4, 1938, Vol. 29, No. 19, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Bender requests Polio fund drive," College Eye, January 19, 1951, Vo. 42, No. 15, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Berry, Robert. "Off the wall: everything is wrong about being sick," Northern Iowan, February 6, 1981, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Christmas Seals on sale Dec. 1; proceeds to be used for promoting public health,” College Eye, November 2, 1934, Vol. 25, No. 22, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Christmas Seal sale is opened,” College Eye, December 17, 1924, Vol. 16, No. 16, p. 2, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "City mourns death of John H. Rch, former student," College Eye, February 25, 1920, Vol. 11, No. 21, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Correction," College Eye, March 1, 1957, Vol. 48, No. 20, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Craig, Tim. “UNI students still need measles shots,” Northern Iowan, November 10, 1992, Vol. 89, No. 21, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Current student productions meet with mumps casualty,” College Eye, May 23, 1941, Vo. 32, No. 33, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Dr. Frank N. Mead,” Normal Eyte, April 1, 1920, Vol. 4, No. 2, p. 3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Dr. Hillis postpones his lecture," Normal Eyte, January 26, 1901, Vol. 10, No. 17, p. 410, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Dr. Kepford talks; interesting lecture on Tuberculosis given Tuesday night," College Eye, April 10, 1912, Vol. 1, No. 24, p. 5, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Editorial,” College Eye, April 12, 1911, Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 57, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Ella McNean,” Students' Offering, May 1, 1880, Vol. 4, No. 12, p. 7, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Epidemic is over,” College Eye, February 15, 1952, Vol. 43, No. 18, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Etta Thomas,” Normal Eyte, February 1, 1905a, Vol. 15, No. 18, p. 286, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Etta Thomas,” Normal Eyte, January 25, 1905b, Vol. 15, No. 17, p. 269, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Events revised in effort to curb health dangers," College Eye, October 25, 1957, Vol. 49, No. 7, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Finance Committee here; school to have a hospital,” Normal Eyte, September 29, 1909, Vol. 20, No. 4, p. 67, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Flu cases crowd hospital beds," College Eye, March 21, 1947, Vol. 38, No. 24, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Flu, cold 'shots' ready, says Griffen," College Eye, October 10, 1947, Vol. 39, No. 4, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Flu expected, shots available," College Eye, September 26, 1958, Vol. 50, No. 3, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "'Flu shots offered to college students," College Eye, October 22, 1948, Vol. 40, No. 6, p. 3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Follow directions; prevent epidemic," College Eye, January 10, 1941, Vol. 32, No. 15, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Former students dies at Quasqueton; popular young man passed away after lingering illness,” College Eye, February 6, 1913, Vol. 2, No. 18, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Fromm, Geraldine G. "'Like sitting ducks,' says French, TC Health Director," College Eye, October 18, 1957, Vol. 49, No. 6, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Ground is broken for new dormitory,” Normal Eyte, June 13, 1914, Vol. 4, No. 1, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “G. W. Randlett,” Normal Eyte, March 15, 1902, Vol. 12, No. 23, p. 36, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Hagerman, Brian. "Flu Going around, resting may help," Northern Iowan, February 10, 1989, Vol. 85, No. 36, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Harkin, Brad. “Health Center offers free measles vaccination,” Northern Iowan, April 1, 1983, Vol. 79, No. 45, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Have you had the grippe?," Normal Eyte, January 14, 1899, p. 224, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Health Center busy--100 outpatients a day," Northern Iowan, January 12, 1968 Vol. 64, No. 28, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Hoelscher, James B. “Measles vaccinations to be required at UNI,” Northern Iowan, August 30, 1991, Vol. 88, No. 1, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Hong Kong flu vaccine ordered," Northern Iowan, December 13, 1968, Vol. 65, No. 27, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Hyde, Mary Alice. “Small pox nevermore,” Old Gold, June 1, 1911, Vol. 0, No. 0, p. 253, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Ina Rue passes away; influenza victim," College Eye, October 15, 1918, Vol. 10, No. 1, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Influenza causes hospital overflow," College Eye, January 30, 1953, Vol. 44, No. 17, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “It seems some people really neglect to have measles,” Normal Eyte, January 20, 1894, Vol. 3, No. 17, p. 134, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Jenkins, Lance A. “Mumps menace: one shot not enough,” Northern Iowan, September 8, 2006, Vo. 103, No. 4, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Kelly, Ned. "Flu shot shortage not expected to get better anytime soon.," Northern Iowan, October 29, 2004, Vol. 101, No. 18, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Kimmel, Jan. "The Bug," College Eye, October 25, 1957, Vol. 49, No. 7, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Krebs, Mike. "Flu outbreak to reach new heights," January 13, 1978, Vol. 74, No. 34, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "La Grippe," College Eye, November 24, 1915, Vol. 7, No. 10, p. 7, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Last week,” Normal Eyte, January 16, 1895, Vol. 4, No. 20, p. 314, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Lawther laurels nurse--'Caswell Day' declared," College Eye, December 6, 1957, Vol. 49, No. 12, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Lecture on tuberculosis; Dr. Whittaker, government lecturer, gave interesting lecture Friday evening.,” Normal Eyte, October 27, 1909, Vol. 20, No. 8, p. 138, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Little is known about paralysis, says Dr. Durfee,” College Eye, October 4, 1940, Vol. 32, No. 4, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Local and personal.," Normal Eyte, February 6, 1897, Vol. 6, No. 18, p. 212, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Locals,” Student's Offering, March 1, 1883, Vol. 7, No. 29, p. 5, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Lovelace, Todd. "Flu shots available at Health Center," Northern Iowan, October 27, 1998, Vol. 95, No. 17, p. 3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mabel Clayre Harkin," Alumni News Letter, April 1, 1919, Vol. 3, No. 2, p. 3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Maltby, Craig. "No 'quick cure' for flu," Northern Iowan, February 3, 1981, Vol. 7, No. 30, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Many of the students,” Normal Eyte, January 25, 1896, Vol. 5, No. 16, p. 144, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Marie Zimmer and Jessie Sutter,” College Eye, May 12, 1926, Vol. 17, No. 44, p. 5, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- McManus, Thomas. “The Bath Tub Movement,” Normal Eyte, February 28, 1893, Vol. 2, No. 21, p. 164, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Measles, an unwelcome visitor,” Normal Eyte, April 30, 1904, Vol. 14, No. 31, p. 491, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Measles epidemic,” College Eye, February 8, 1952, Vol. 43, No. 17, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Measles, grip, tonsillitis,” Normal Eyte, February 5, 1908, Vol. 18, No. 18, p. 276, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mild case of polio hits frosh student," College Eye, October 11, 1946, Vol. 38, No. 5, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Miss Call's Name," Normal Eyte, February 13, 1897, Vol. 6, No. 19, p. 224, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Miss Drenning,” Normal Eyte, March 14, 1906, Vol. 16, No. 24, p. 383, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Miss Elizabeth Hart,” College Eye, February 27, 1924, Vol. 15, No. 24, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Miss Hazel Cole," College Eye, January 28, 1920, Vol. 15, No. 24, p. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Miss Irene Stevens," College Eye, May 18, 1921, Vol. 12, No. 34, P. 8, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Miss Kathryn Heddens,” College Eye, April 19, 1911, Vol. 1, No. 5, p. 85, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Miss Mary Dougherty," College Eye, October 23, 1918, Vol. 1, No. 2, p.3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Miss Vera De Seelhorst,” College Eye, April 26, 1911, Vol. 3, No. 26, p.440, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mr. Page," Normal Eyte, January 12, 1899, Vol. 8, No. 17, p. 239, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mrs. D. S. Wright," Normal Eyte, January 18, 1911, Vol. 21, No. 16, p. 286, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mrs. Homer H. Seerley," Normal Eyte, January 11, 1911, Vol. 21, No. 15, p. 266, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Mrs. Seerley," Normal Eyte, January 14, 1899, Vol. 8, No. 16, p. 224, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “National tuberculosis head to address assembly Oct. 31,” College Eye, October 20, 1944, Vol. 36, No. 7, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- “Nearly 600 vaccinated during past week; all are urged to cooperate in prevention of epidemic,” College Eye, January 14, 1925, Vol. 16, No. 17, p.1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Notes and comments," Normal Eyte, February 6, 1897, Vol. 6, No. 18, p. 213, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Notice," College Eye, March 22, 1957, Vol. 48, No. 22, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Official Suggestions," College Eye, October 18, 1957, Vol. 49, No. 6, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "On the morning of August 24...," Normal Eyte, September 6, 1902, Vol. 49, No. 6, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Oppose Cornell, Coe this week end," College Eye, December 13, 1928, Vol. 20, No. 14, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Outbreak of influenza hits UNI campus; over 100 cases reported daily," Northern Iowan, February 9, 1979, Vol. 75, No. 34, p. 7, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- Pierce, Leslie D. "Flurry of flu cases hits UNI," Northern Iowan, March 11, 2003, Vol. 99, No. 43, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Polio vaccine now available," College Eye, April 10, 1964, Vol. 58, No. 24, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Polio victim recovers gradually at home," College Eye, December 20, 1946, Vol. 38, No. 14, p. 7, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "President resumes duties following attack of flu," College Eye, February 26, 1932, Vol. 23, No. 32, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Professor Fagan," College Eye, October 23, 1918, Vol. 10, No. 2, p. 3, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Professor Reuben McKitrick," Alumni News Letter, April 1, 1919, Vol. 3, No. 2, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Professor Underwood," College Eye, February 5, 1919, Vol. 10, No. 13, p. 4, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Professor Wallace will not return this term," College Eye, April 1, 1932, Vol. 23, No. 36, p. 1, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Prof. Condit," College Eye, February 13, 1913, Vol. 2, No. 19, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

- "Prof. Merrill," College Eye, February 13, 1913, Vol. 2, No. 19, p. 6, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.