Television at UNI - A History

Introduction

A college campus is sometimes a center for the introduction, use, and development of technological advances. This series of brief essays looks at the introduction and development of various technologies at the University of Northern Iowa. Each essay is arranged in a generally chronological way. There is frequently considerable controversy about the inventors of particular technologies and the exact date on which their work became available to the public.

These essays will not attempt to settle those questions. Rather, these essays will tend to follow generally accepted historical evidence and practice. Likewise, these essays, for matters specific to the University of Northern Iowa, will simply present readily available evidence. The writer of these essays welcomes corrections and additions.

A remarkably forward-thinking editorial appeared in the Iowa State Normal School (now the University of Northern Iowa) student newspaper, the Normal Eyte, on February 2, 1892. The editorial noted the inception of something called the theaterphone (théâtrophone), which, via a telephone connection, brought the sound of musical and dramatic performances to high end hotels in London and to personal subscribers in Paris. This novel device even offered a semblance of stereophonic sound. While this particular service was limited to the transmission of sound to a small and select group, the anonymous editorial writer invoked Edward Bellamy, author of the popular utopian novel Looking Backward, 2000-1887, and speculated on potential additional dimensions of that kind of service. The speculation is worth quoting in its entirety:

With such marvelous achievements being continually made in the scientific world, who can say what possibilities lie yet before us? No doubt some future editor of the Normal Eyte will be able to sit in an easy chair within his sanctuary with his feet on the stove and order on the European plan a scene from Hamlet or turn on a selection from Gilmore's band or even listen to and see the countenance of the President of the U. S. delivering his inaugural address.

Whoever wrote that editorial had extraordinary foresight. Viewing and listening to music and drama--and even to political events--from an easy chair at home would not be common until almost sixty years later. Receiving specific programming on demand would come even later than that. The anonymous Normal School writer from 1892 showed an uncanny ability to look ahead to things that he might never experience in his entire lifetime.

Early Years, 1950-1965

Engineers and scientists had been working on the concept of television as far back as the 1880s. But things did not really begin to come together in a practical way until the 1920s, when the news media would report occasional advances in that field of study. So, people came to know the word "television" fairly early, but few admitted the concept as anything approaching a commonplace reality. An article in the student newspaper, the College Eye, nicely characterizes what people thought of television. The 1928 April Fool's lampoon edition of that newspaper reported that the college administration was planning to make handball a major college sport that could be viewed on a television in the Auditorium. In other words, installing a viewable, accessible television on the Teachers College campus was about as likely as the possibility of making handball a major college sport. Students of that day were quite familiar with motion pictures. And sound was beginning to be added to some feature films at that time. But television still seemed to be a long way off.

A television broadcast was a highlight at the opening of the New York World's Fair on April 30, 1939. A speech by President Franklin Roosevelt was broadcast to about two hundred television sets in and around New York City. With this speech, the National Broadcasting Company began its schedule of regular broadcasts in that city.

World War II absorbed most of the nation's technological and production energies over the next few years. And, after the war, media companies needed time to organize themselves and their affiliate stations for widespread broadcasting. So, progress in local, commercial television, especially in small markets such as Waterloo/Cedar Falls, was stagnant for a number of years.

In 1950, television seemed to jump into the consciousness of students and faculty at the Teachers College. On March 10, 1950, an article in the student newspaper mentioned that talent was needed for a broadcast of Ted Mack's "The Original Amateur Hour" that would be televised from Des Moines in April. Just two weeks later, Broadcast Services Director Herbert V. Hake announced that the upcoming national collegiate wrestling championship tournament, to be held on the Teachers College campus, would be filmed. That film would be shown on Ames television station WOI a week later, with Teachers College wrestling coach Dave McCuskey providing commentary. The films were also shown on station WOC in Davenport. This was great publicity for the already strong Teachers College wrestling program. The college received additional athletics coverage when films of the spring Teachers College Relays were shown on WOI. Coach Art Dickinson provided commentary on those films. In that same year, Mr. Hake was also involved in another early television effort when he and Director of Safety Education Bert Woodcock put together a series of television films on safety education.

Demand for educational films that could be shown on television had apparently been growing steadily in the postwar years. In the spring of 1950, the Board of Education (now the Board of Regents) approved the expenditure of $7000 for the purchase of sound motion picture production equipment. The equipment would be used to produce educational films for classroom use, but there was also a clear intention of producing films for television broadcast. Mr. Hake would be in charge; audio-visual specialist Waldemar Gjerde would assist with the technical aspects of the work. Mr. Hake stated:

Starting in the fall we expect to produce films in safety education, science, music, athletic events as well as interviews with outstanding visiting personalities and the visualizing of

other educational features.

The $7000 would go toward the purchase of two Oricon sound motion picture cameras, editing and lighting equipment, tripod trucks, and scenic backgrounds. The equipment would be installed in the radio studios on the third floor of the Auditorium Building (now Lang Hall).

In late June 1950, technicians installed a thirty foot antenna on top of the Auditorium roof. This antenna allowed the Teachers College to receive the signal from WOI-TV in Ames. The signal would feed into a sixteen-inch television monitor in the Auditorium broadcast offices. At that time, the purpose of receiving the television signal was not so that a general audience could watch television. Rather, Mr. Hake explained that the receiver would be used to check the quality of the programming that the Teachers College would furnish to WOI on a weekly basis. By the start of the fall 1950 term, the studios had been remodeled and the new equipment had been installed. The first regularly scheduled Teachers College television program, a film on safety education featuring Bert Woodcock, aired on WOI on October 5, 1950. Thereafter, Teachers College programs were shown on WOI on Thursdays at 6:30PM. The Teachers College break-through into broadcast television was a featured item in most campus year-end news wrap-ups.

In July 1951, student Darrell McKibbin won a television set worth $370 in a local contest. He brought it back to his room in Seerley Hall for Men so that his friends could admire it. But then he took it home to his parents' house. Without a local network affiliate station or a very tall antenna to receive the signal of a distant station, a television set did little good on campus.

Mr. McKibbin's good fortune presents an opportunity to look at the investment necessary to buy a television set in 1951. A black and white twenty-one inch television cost about $400. At that time, median annual household income in the United States was about $4000. Buying a television set cost more than a month's income. And, if the household was in an area not served by a nearby television station, there would be an additional cost to install a forty or fifty foot antenna. What is more, early television sets were not especially reliable. A visit from a repairman to replace burned out tubes was a regular part of life in the 1950s. Buying, installing, and maintaining a television was a costly matter in those early days.

While most Teachers College students were simply looking forward to being entertained by television programming, some considered the serious side. Students were already talking and thinking about television and its influences. As with most technologies, television had its strengths and shortcomings. An editorial in the student newspaper, the College Eye, asked students to consider carefully the things that they might see on television. Did the programming have good values? Did it occupy time that might be better spent in study, healthful outdoor activity, or thoughtful solitude? Did it take the place of a good book? The editorial writer thought that future teachers had a responsibility to face the challenges that television would present. Students interested in the technical side of television likely attended a May 1952 presentation on color television by engineer James L. Hollis, when he addressed a meeting of Lambda Delta Lambda, the physics honor society. Faculty and staff who attended a campus conference on television in the summer of 1952 supported a proposal to establish a state educational television network. This proposal eventually went to the General Assembly with a $4 million price tag. In this plan, the Teachers College would be one of the originating stations.

In the fall of 1952, Teachers College Professor John Mitchell began a new show, "Music Time", on WOI. The show was aimed at providing instruction to elementary school students. That same fall the college also produced programming in science, dance, and nature study. Faculty members responsible for those programs included Ellen Aakvik, Roy Abbott, and Henry Harris.

In September 1953, Dean of Students Paul Bender announced that it might be possible to install a television in the Commons for "special television events of great public interest". The special event in this case was the World Series. The student governance body of that day, the Student League Board, decided that the television would be located in the small lounge in the Commons. Board president Ron Roskens announced that the Board would use profits from the upcoming Duke Ellington concert to help cover purchase and installation expenses. The target was September 30, 1953, the starting date of the World Series. A television set was indeed installed. Students saw the New York Yankees defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers in six games. The series was carried by NBC, with Mel Allen and Vin Scully calling the games. It is interesting to consider which NBC affiliate the students watched. The Waterloo NBC affiliate, KWWL, did not begin broadcasting until several months later, November 29, 1953. For the World Series in 1953 and for the Iowa high school basketball tournament in 1954, the television was placed on the stage--like a human performer--in the Commons Ballroom, but afterward it was placed in the small lounge.

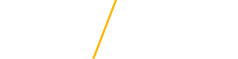

1953 was a watershed year for broadcast television in eastern Iowa. The first station, KGAN in Cedar Rapids, began broadcasting on September 30, 1953. KCRI (later KCRG), also in Cedar Rapids, followed on October 15, 1953. And, as noted above, KWWL in Waterloo, began its broadcasts on November 29, 1953. So, by late fall, local viewers had access to the programming of three major networks. The men of the Seerley Hall for Men were quick to jump on the television bandwagon. By early November 1953, they installed a television, purchased with funds from pop and candy sales, in the large solarium lounge on the south side of their dormitory. Richard Potts and Clyde Greve were responsible for the purchase and installation. In order to avoid conflicts with study time, the television was turned off at 10PM on Sunday through Thursday nights. The Seerley men made a social occasion of television viewing with a weekly Date Night. On that night, men could bring their dates to the lounge for an evening of television viewing, card playing, or radio listening. The friendly, informal atmosphere of Date Night was a big hit. By the fall of 1954, Stadium Hall, a makeshift residence area in O. R. Latham Stadium, also had a television. Interest in television was so pervasive in 1954 that the women's synchronized swimming group, the Marlins, used television as the organizing theme for their spring show.

Also in 1954 President Maucker mentioned television specifically as an area of fiscal need. And, in December 1954, Professor Josef Fox, one of the best instructors at the Teachers College, began teaching Humanities I as an extension course over WOI. The course consisted of twelve Saturday morning lectures and two written papers, culminating with final examinations at both Ames and Cedar Falls. Professor Fox, a strong proponent and exemplar of teaching excellence, put on memorable performances in the new television medium.

Mr. Hake and the Teachers College faculty continued to produce an extraordinary variety of educational programming that was aired on WOI in Ames. WOI also featured special productions involving Teachers College students. In January 1954, forty-five members of the Teachers College Band traveled to Ames to perform in a half hour program. However, WOI programming was out of the broadcast range of most viewers in the Waterloo/Cedar area. Mr. Hake hoped that at least some college programs would soon be shown on Waterloo's KWWL. Shortly thereafter, KWWL broadcast a WOI-produced program called "TC on TV". Two members of the Teachers College art faculty, Robert von Neumann and David Dreisbach, showed their work on that program in March 1954. In the fall of 1954, Professor Wray Silvey offered the first extension course in Iowa aimed specifically at practicing teachers. He traveled to WOI in Ames to teach the course, "Educational Tests for the Elementary School". The live broadcasts were put onto kinescopes so that they could be used at other Iowa stations.

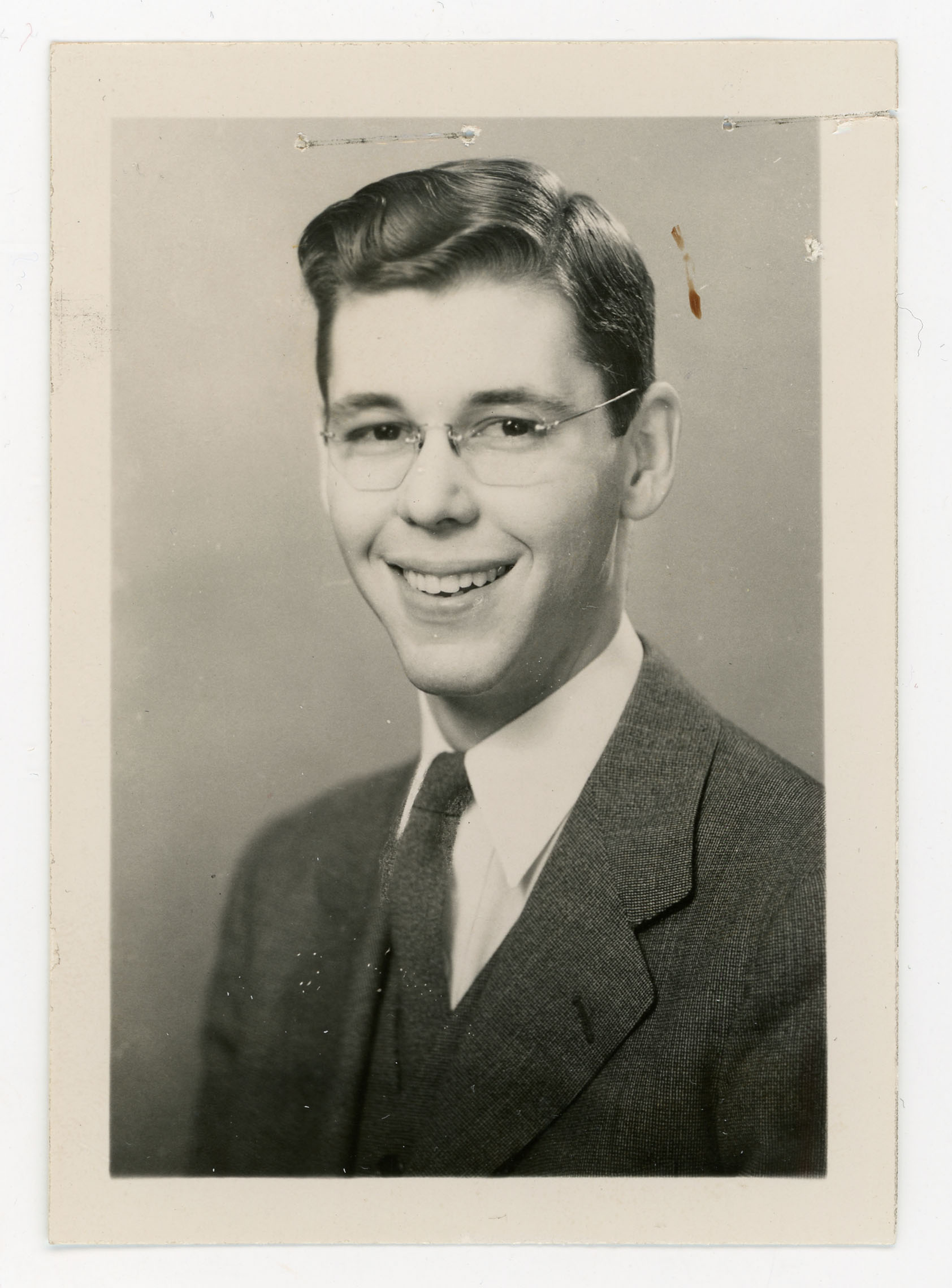

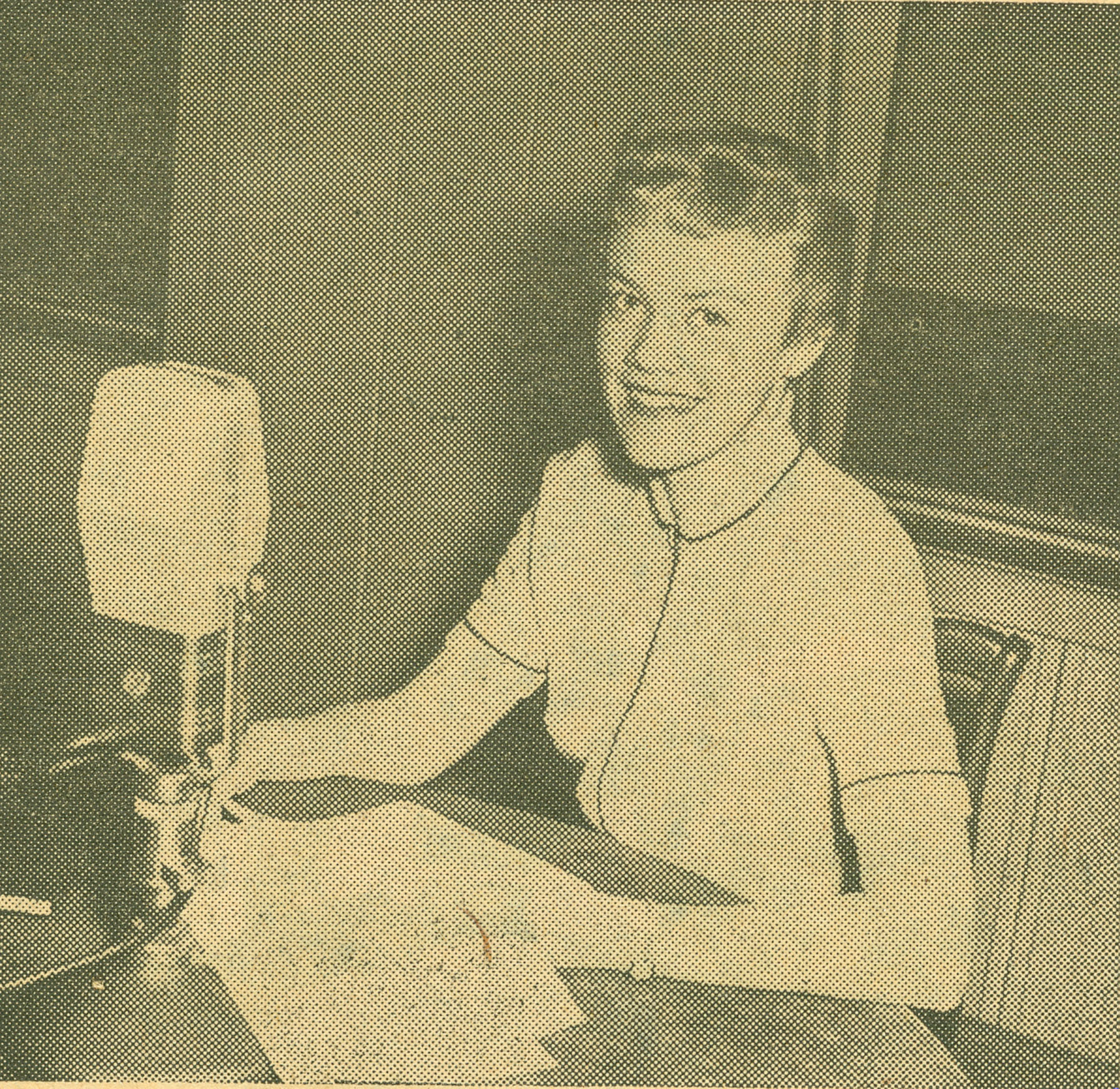

In those early days, the Teachers College even had a local television celebrity. Arjes "Sunny" Sundquist had been a Teachers College student when an opportunity in children's programming opened at WOI. She had been assisting Mr. Hake with radio work on the Teachers College campus, so Mr. Hake told her about the WOI opportunity. Miss Sundquist, winner of the Miss Cedar Falls contest in 1953, interviewed for and accepted the position at WOI. There, beginning in January 1954, she was host to two children's programs: "Magic Window" for younger children and "Window Watchers" for older children. Her programs, incorporating the arts, music, science, nature, and social studies, attracted a wide following. People recognized her in the street and sent her a large volume of fan mail. When the programs ended after about a year, Miss Sundquist returned to Teachers College. After graduation, she planned to teach in the Iowa City area and to marry her fiance, who was in medical school there.

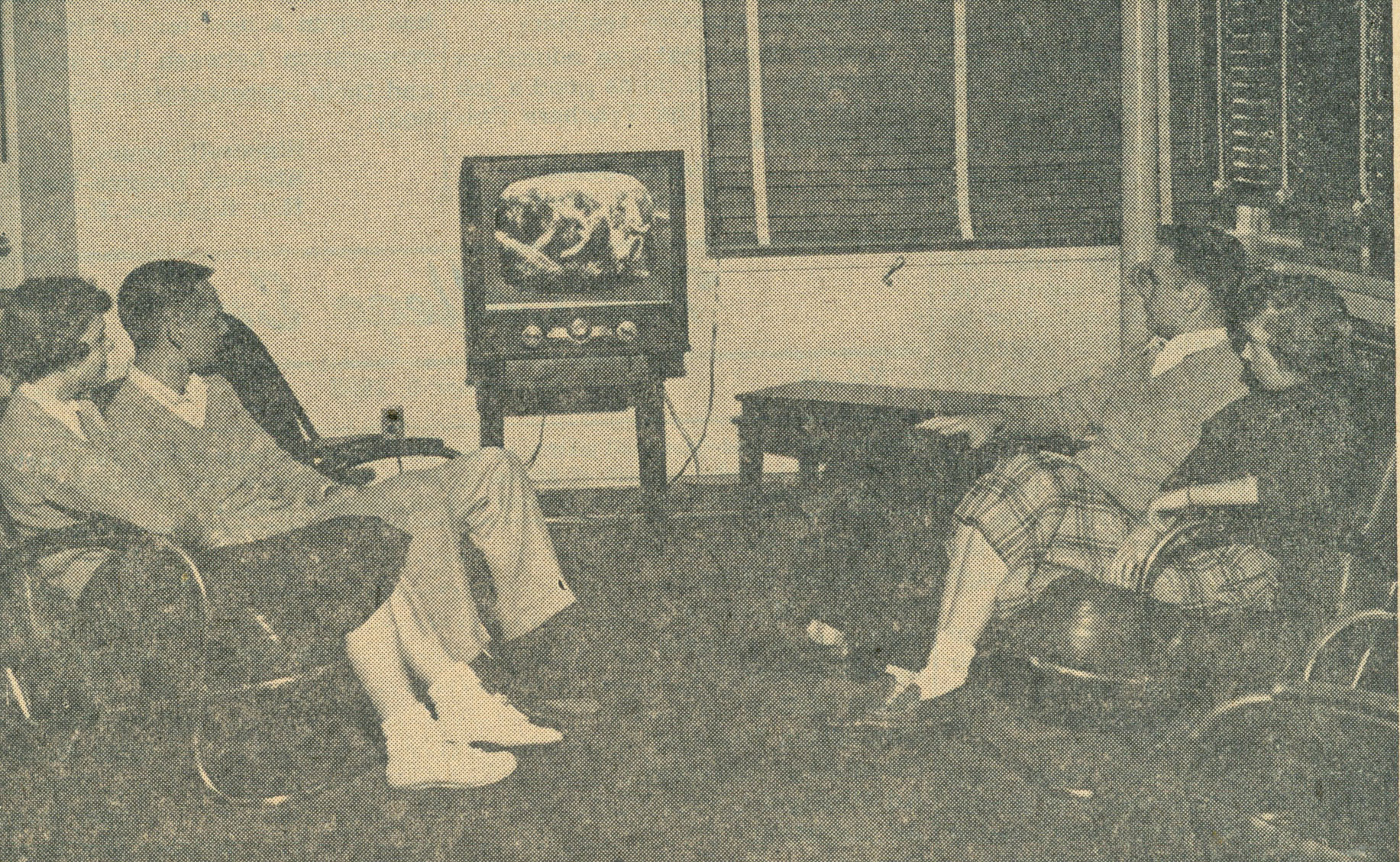

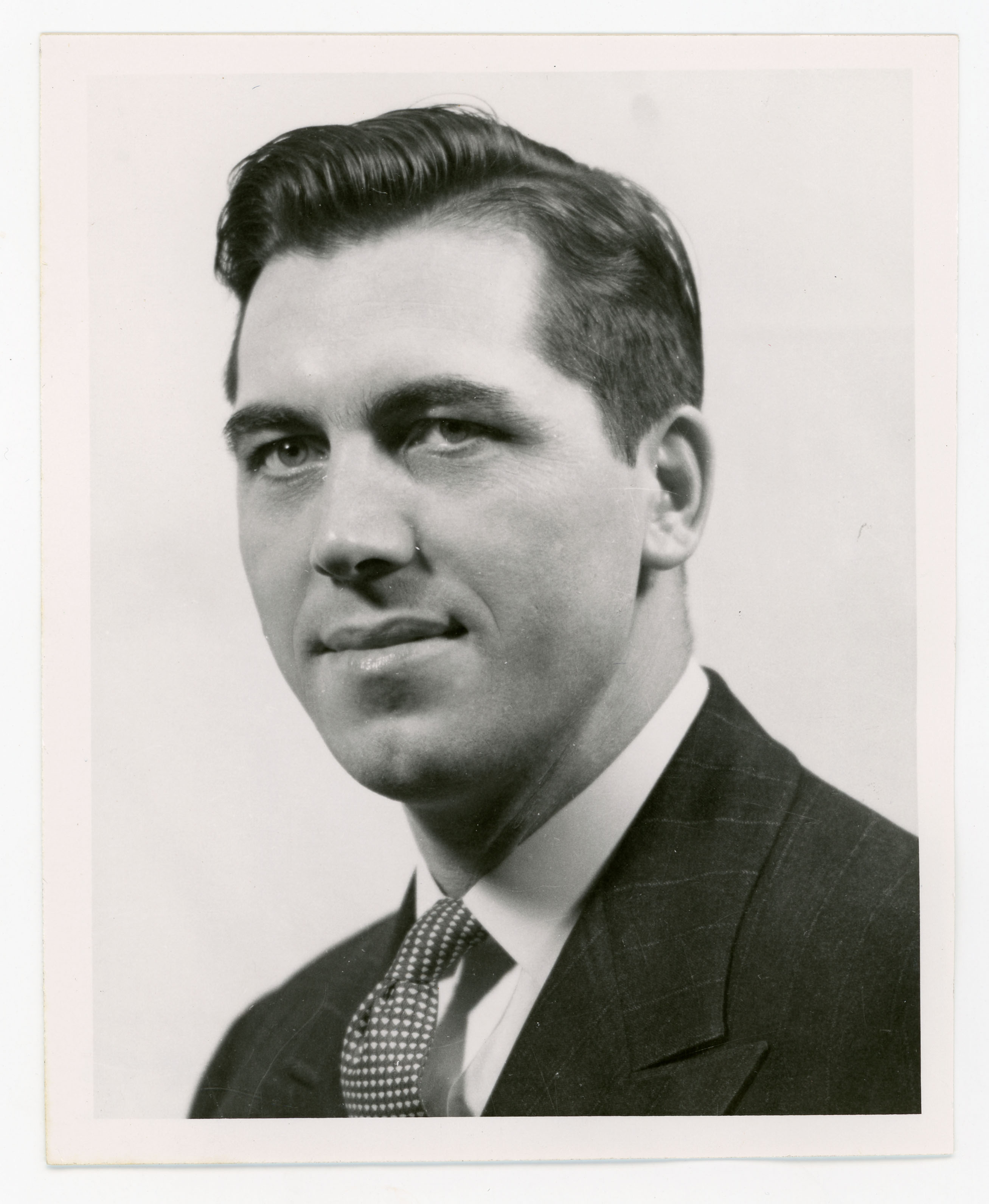

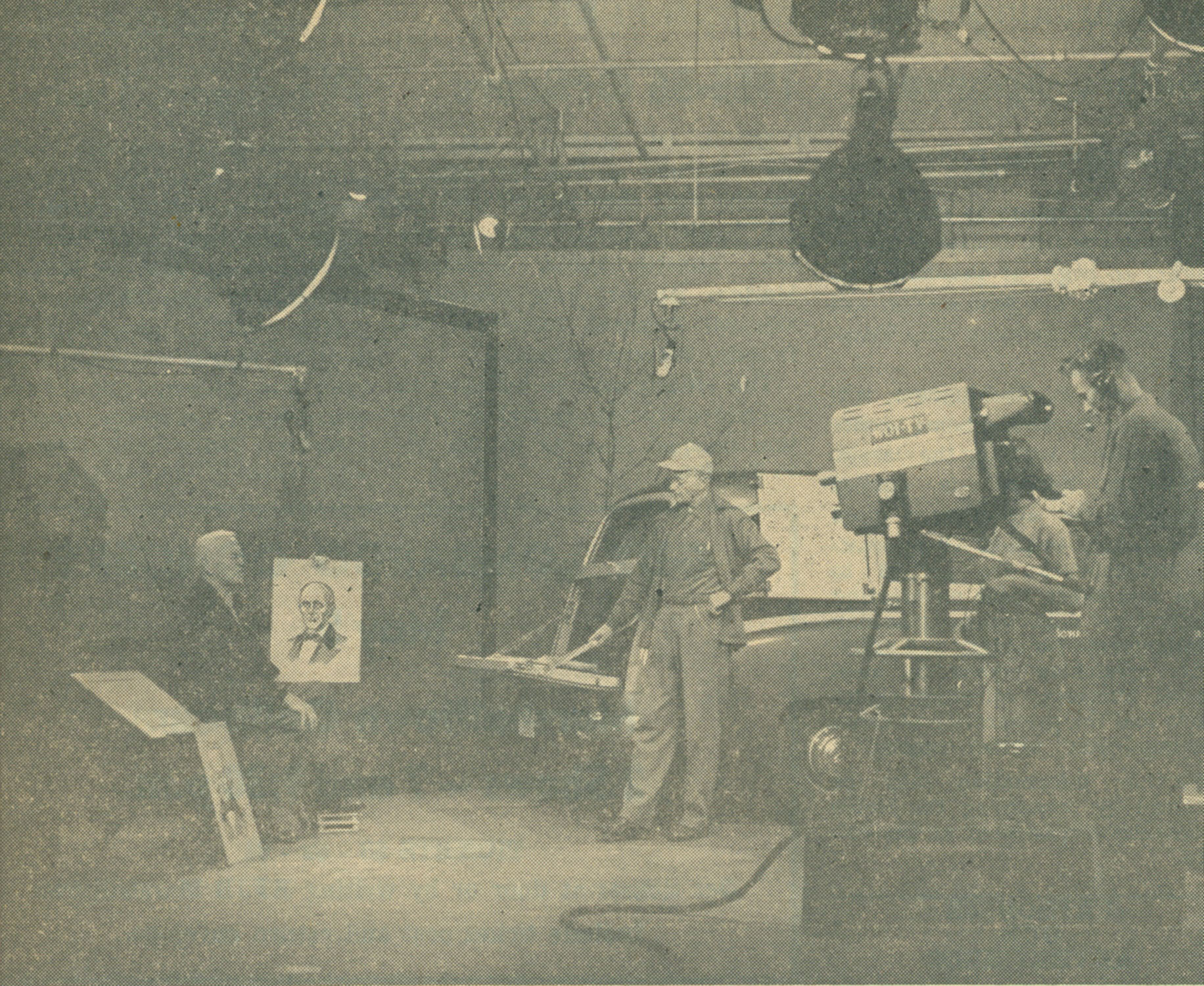

Mr. Hake himself was a very talented man. He was an actor, director, set designer, producer, teacher, artist, cartoonist, and popular historian. When the Teachers College took its first steps in radio and then in television, Mr. Hake was the guiding hand. By the mid-1950s, he had begun to produce several longstanding series on Iowa history. A generation of Iowa schoolchildren learned to recognize Mr. Hake, his voice, his stage backdrop, and his historical interpretations. Already in 1955 his "Landmarks of Iowa History" had won a national award. Mr. Hake would ultimately be inducted into the Iowa Broadcasters Hall of Fame in 1976.

By 1956, Mr. Hake was investigating the possibility of using closed circuit television on campus. With the Teachers College limited to just three broadcasts per week on WOI, closed circuit television would allow more local programming to be delivered to specific campus audiences. The signal would not be broadcast, but closed circuit television had strong potential for use on campus. For example, a faculty member could deliver a lecture in one classroom, but his lecture could be viewed in a number of other classrooms. That would allow the faculty member to teach very large classes. In addition, a closed circuit system would allow a visiting speaker or lecturer to be viewed widely on campus.

Citation: Television stage set at WOI in Ames, 1955, in The College Eye student newspaper collection, 17/01/01/03, Vol. 46, University Archives, Rod Library, University of Northern Iowa.

Television took a fair amount of criticism even in those early days. Some criticized those who watched television instead of doing something more productive. One student newspaper article questioned the veracity and intent of a televised history of World War II that seemed to be overly harsh on the Japanese. Another student wrote that it was much more interesting to watch television viewers than it was to watch television itself.

Professor Josef Fox had strong things to say about the new television addiction. He stated that utopian writers had maintained that if people were relieved of some of the drudgery of work, they would devote themselves to intellectual pursuits. But that did not seem to be happening. Most people preferred watching "I Love Lucy" to reading Plato. Professor Fox believed that the way in which people were educated made the difference between utopian predictions and actual behavior; he thought that people should be learning good values in school, but, instead, they were learning poor values from the mass, commercialized communications system. He believed that the mass communications system used more efficient teaching methods and commanded more time and money than did the school systems. Nonetheless, Professor Fox believed in the potential strength of classes transmitted via television. In fact, he stated that there was no need whatsoever for further study into the matter of the effectiveness of television. Television worked. No question. But his significant reservation was that people needed to be active and engaged listeners. And that, he said, was exceedingly unlikely. People had always found ways to learn only as much as they absolutely needed to learn. There was no reason to think that television would change that attitude for the better. After teaching several courses via television, Professor Fox stated that he believed that television was an effective means of conveying facts to an audience. However, he also believed that there was much more to teaching and learning than statements of facts. He believed that both faculty and students benefited from the personal contact and discussion found in traditional classrooms. He concluded a March 1960 "Obiter Scripta" column by saying:

Anytime the administration wants to junk its TV equipment and move me back into the classroom, I'll be ready.

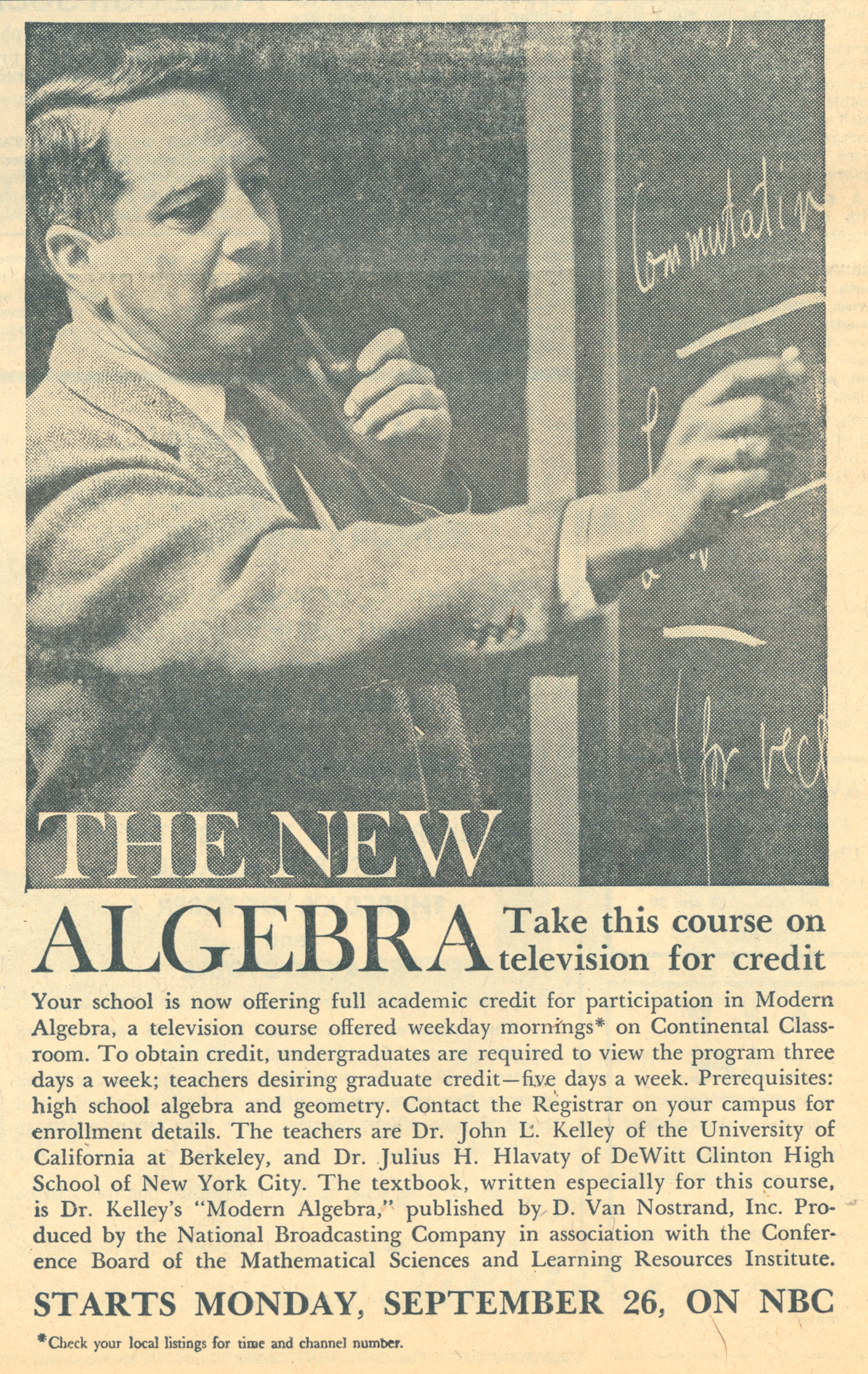

The Teachers College moved quickly on the installation of a closed circuit television system at the eventual cost of about $20,000. In the spring 1958 semester, Professors Dorothy Matala and George Worley presented "Physical Science for Elementary Grades" via closed circuit. Both faculty members had had previous experience with television classes. Three times a week, Professors Matala and Worley presented lectures from the television studio to students in two classrooms in the Auditorium Building. Each of those classrooms had two television monitors. Each student was assigned to a laboratory session under the direct supervision of Professor Matala or Professor Worley. Examinations were given during lecture class sessions. The Science Department stated that this class was being offered on only an experimental basis and that it would be taught with the academic rigor found in non-television classes. That same year Professor Robert Rogers coordinated local arrangements for a nationally broadcast physics course in NBC's "Continental Classroom" series. The next year Professor Rogers and Professor James Kercheval coordinated a nationally broadcast chemistry course in that same series. Contemporary mathematics classes followed.

Students and faculty seemed pleased with the results of those courses; consequently, the Teachers College allowed credit for successful completion of work in those televised classes.

More and more people were beginning to understand the significance of television on a national scale. Following the first Presidential debate between candidates Richard Nixon and John Kennedy in 1960, an editorial in the student newspaper stated that televised debates could very well help to distinguish candidates, especially those who were running in close races and on similar party platforms. The editorial concluded by saying:

These televised sessions could play a very important part in forming the opinion of the American voter and will undoubtedly influence the political campaigns of the future.

Beginning in October 1960, Dick Edwards, a student newspaper reporter, wrote a series of articles on closed circuit instruction on campus. Due to a lack of classroom space and a growing enrollment, campus administrators were looking hard at the expansion of course offerings via closed circuit. Mr. Edwards asked Mr. Hake to defend televised instruction. More appropriately, questions about the quality of closed circuit instruction should been addressed to high-ranking Teachers College instructional officials such as the president, the dean of instruction, or department heads. Nonetheless, Mr. Hake defended the position ably. First, he noted objective evidence that students did as well or better in televised classes. Second, he responded to those who decried the lack of personal contact between students and faculty in closed circuit classes. Mr. Hake pointed out that this was really nothing new. There had, after all, been little personal contact between students and faculty in a 250-seat lecture hall taught in person by a member of the faculty. Mr. Hake made it clear that closed circuit instructors personally taught lab and quiz sections associated with the televised classes. Mr. Hake also pointed out that televised classes, especially in science, allowed for close-ups of demonstrations that would be difficult to see clearly from the back of a typical classroom. He believed that televised classes would obviously not work for subjects that demanded considerable discussion. But for classes that required the transfer of a great deal of factual information, televised classes were the best solution for the increasingly crowded Teachers College campus facilities.

In the next part of Mr. Edwards's College Eye interview series on televised classes, faculty members gave their impressions of this new way of teaching. Their opinions were firmly divided. Some thought it was fine; others had no use at all for it. Just about all of those who were interviewed thought that face-to-face teaching was best. But science and mathematics professors thought that televised courses seemed to work fairly well. They pointed to successful outcomes in terms of student grades and achievement. Humanities and social science professors tended to be strongly against televised courses, or considered them a necessary evil in a difficult enrollment situation. They did not see how proper learning in their fields could be fostered in such an artificial environment. Just about all of the professors found that the timing of their lectures was especially difficult. Were they going too fast or too slow? Were students picking up on what they said? Without the reinforcement of expressions on students' faces, they found it hard to tell.

In the last article in the series, Mr. Edwards sought the opinions of students on closed circuit instruction. Unfortunately, he spoke with only a few students, so any information reported in the article must be weighed against the limitations of a small sample size. In any case, students' opinions contradicted those of the faculty to a certain extent. Students in televised science classes were not especially happy with their experiences. They believed that camera work was too slow to catch up with demonstrations and that seeing things in person and in color was far superior to the black and white televised images. Mathematics students said that they missed the opportunity to follow up quickly on things that they did not understand. In-room proctors helped, but perhaps not with the immediacy that students desired. Those mathematics students who were interviewed said that they could not recommend a televised mathematics class to others. On the other hand, students loved Professor Ross Jewell's English composition class. They said that they learned a great deal and that the class moved along well without getting bogged down in useless discussion. Some of the students interviewed did not especially like the graders employed by some professors to evaluate large numbers of essays. And all of the students noted frequent technical problems with the television monitors.

Teachers College administrators appreciated the potential public relations value of broadcast television. On several occasions President James W. Maucker appeared on local television stations to make the case for increased funding. In anticipation of the Baby Boomer enrollment spike, it was critical to reach the public directly about the needs of a growing college. Likewise, athletics benefited when KWWL showed films of some of the 1961 football games on Sunday afternoons. Coach Stan Sheriff provided commentary. In November 1961, KWWL began a series of half-hour programs on the academic departments of the college. The first program featured Professor Don Finegan from the Department of Art. Later programs featured the Departments of Social Science, Physical Education for Women, Physical Education for Men, and Language and Speech. KWWL presented another series, "Artist's Studio", devoted specifically to the Department of Art in 1963. In February 1965, President Maucker and Dean William Lang were featured on yet another KWWL program entitled "College Close-up", where they discussed campus matters such as appropriations, admissions, and the objectives of a college education. Among the appropriations sought was funding for a closed circuit connection between the Price Laboratory School and campus classrooms. This capability would make it possible for students in on-campus theory and educational psychology classes to view class work in the Laboratory School. Both President Maucker and Dean Lang were extraordinarily strong and capable spokesmen for the college.

For a number of reasons, commercial use of color television was very slow to be adopted. Even though networks were capable of producing and broadcasting color images, the conversion process from black and white to color was expensive for both networks and consumers. Networks would need to re-tool their production lines, and consumers would need to buy new television sets. In 1964, only about 3.1% of American households had color sets. It would be several more years before networks began full color prime time programming. Some students wished to keep up with trends. So, in 1965, a student political party proposed the installation of color televisions in the men's dormitories. It is not now clear if this party won or if color televisions were indeed installed as a result.

Growth and Development, 1966-1994

There is no question that television, especially the entertainment side, was popular among students during its first decade or so on campus. It is also clear that the school used the television medium to develop a broad range of sound, educational material. Over the next decade, this medium would undergo substantial change and development, which would affect both entertainment and more serious programming. Perhaps until about 1965, television was trying to find its own commercially successful operational model. Was it like a theater? A newspaper? A debate forum? A lecture hall? A sports stadium? A movie house? An artists' studio? A vaudeville house? Should it be serious or comic? "Meet the Press" or Milton Berle?

People brought old models or analogies to television operations; things just needed to sort themselves out. Of course, the commercial value of a production was a powerful influence on any programming decision. Ultimately it seems as if sports and entertainment won, with a much smaller amount of serious programming scheduled at off-peak hours. Educational programming did not vanish, but it did seem to get sidetracked onto specialized, non-commercial channels that did not interfere with more valuable commercial enterprises.

As it did on many college campuses, the "Batman" television show craze hit the UNI campus hard in 1966. Dormitory lounges that comfortably held fifty residents were crammed with twice that number. Viewers shouted, threw popcorn, and had a good time. As several residents noted, it was a completely different kind of television program. The cartoon graphics and stop action shots of that program were crude by today's standards. But they were new, exciting, and fun in 1966. "Batman" is probably a good example of how the entertainment side of television changed in the mid-1960s. The show was meant to be fun, and it was. Moral values were still clear: good triumphed over evil, but victory came in broad cartoon strokes, rather than in tiresome, philosophic debate. Even the caricatured figures of evil, such as Batman's arch enemies, were fun. But the cause of the change in television is complex. Was it that television ratings services were becoming more accurate about the viewing preferences of identifiable groups? Was it the change to color television? Was it that television viewers, especially the young, already lifelong viewers, wanted something flashier, different, and more in tune with their values? Was it that networks, sensing that a young generation of television watchers was hooked, would do almost anything to keep that generation hooked? Was it that cheap, functional, portable televisions were more widely available? Was it that people felt secure enough to have time for pleasurable and escapist entertainment? Or, on the contrary, were they fleeing from a frightening world?

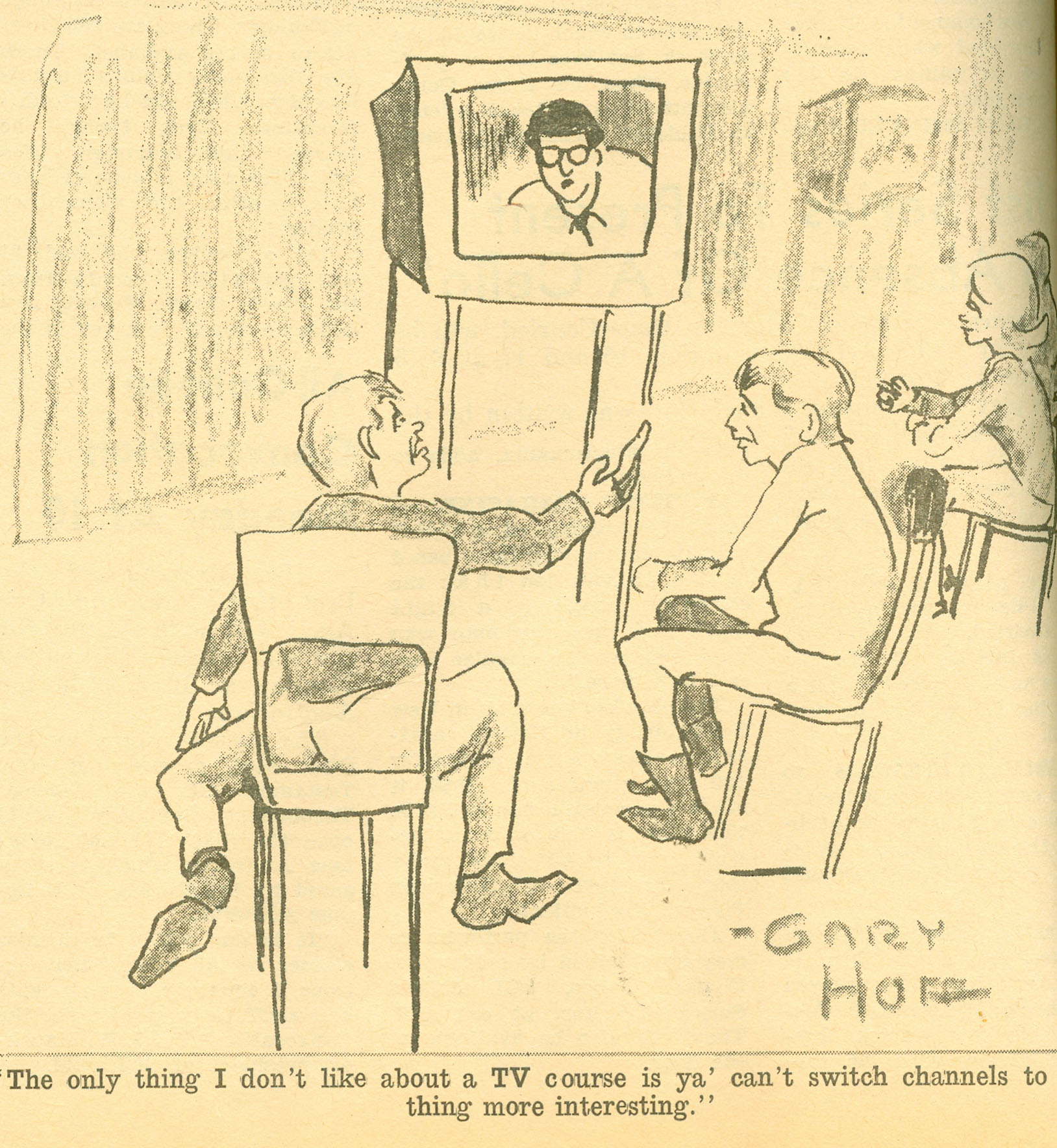

Whatever the cause, the increasingly apparent difference between network programming and educational work was not an immediate, sharp, or inviolable line. Students, especially, appreciated the pure entertainment as well as the news coverage of commercial networks. They also benefited from the college credit classes brought to them on closed circuit television. Faculty continued their sometimes pioneering work in educational media, but they also enjoyed using the low end of commercial television as classroom cannon fodder. College Eye cartoonist Gary Hoff had fun with television on several occasions in 1966.

Professors Edward Thorne and Stanley Wood used videotape in their speech and acting classes at the time when the "Batman" craze was at its height. Students in those classes could quickly review their performances and learn to improve their work. Both professors found this technology to be useful, though with significant limitations. Mr. Hake said, "We have only begun to recognize the potential of video taping."

In 1966, the foundation was laid for what would become the Iowa Public Television Network. During the 1967 Middle East crisis, all networks provided lengthy coverage of United Nations Security Council debate and discussion. A College Eye editorial writer thought that the coverage was too extensive. Unlike those who complained about missing their favorite entertainment programs during this in-depth coverage, the editorial writer took a more thoughtful approach. He believed that extended daily coverage led bored viewers simply to stop watching. He thought that more selective and incisive coverage would lead to a more informed public. Not long afterward, student Roy Behrens (later a member of the UNI art faculty) took a serious look at the ideas of Marshall McLuhan. Mr. Behrens stated that Western culture was moving at an extraordinary speed away from older media--such as the printed word--to newer media, such as television. He believed that people needed to be aware of this shift and be prepared for the radical changes that it would bring.

During the difficult times of the late 1960s, with extensive media coverage of campus unrest, the University of Northern Iowa used the broadcast television medium in two ways. First, there was an effort to show that many aspects of campus life were moving along normally. The Women's Chorus performed Christmas programs on KWWL just about every year. WMT broadcast debates between teams from UNI and the University of Iowa. KWWL broadcast a number of UNI home football games. WMT hosted extension courses. However, the administration also acknowledged campus unrest and took a more direct approach to giving its side of the story to the public. In April 1969, KWWL broadcast a discussion of academic freedom with Professors Leonard Keefe, George Poage, Donald Howard, and Clifford McCollum. Their discussion covered familiar ground: essentially they believed that professors should be able to broach new ideas with their students, but that they should do so responsibly. These four professors probably represented the views of a majority of the university faculty, but they did not reflect the views of their younger and more liberal colleagues who tended to get much more extensive media coverage. Nonetheless, these older, more conservative faculty members were good spokesmen for traditional views on academic freedom. President Maucker and Dean Lang were also seen regularly on KWWL Sunday morning discussion programs. Their thoughtful, intellectual, calm presence was likely reassuring to the public.

During the late 1960s, UNI Extension Services offered a nice array of televised classes, and on-campus closed circuit classes continued to grow. In the fall of 1967, the university made a special effort to relieve the congestion in registration for required general education classes by instituting more closed circuit offerings. As a result, by the fall of 1968, 2600 students were registered in closed circuit class sections. Mr. Hake again cited on-campus studies, which showed clearly that students performed at the same levels in closed circuit classes and traditional classes. But he noted that the existing closed circuit system had reached its technical limit.

In 1971, there was something new on the local communications horizon: cable television. Actually, cable television was not new in the United States. Over twenty years earlier, small communities beyond the reach of broadcast signals had begun to use a wired service to bring television to their homes. There was, of course, a monthly fee for this service. Initially, cable service offered only network broadcast channels. But service expanded in some cases to include local access channels and specialized channels offering only news, music, sports, or movies. That was a tantalizing prospect for television viewers, but a distinct challenge to broadcast networks, which fought hard to prevent cable companies from expanding service into areas already covered by broadcast signals. Voters in Waterloo, Iowa, defeated a referendum to allow cable service in 1971. It would be a few years before cable systems were approved and established in the Waterloo/Cedar Falls area.

The love/hate relationship with television continued among students. One student asked the Northern Iowan to provide a guide to good television programming. Another complained that the World Series broadcast in the Maucker Union interfered with her enjoyment of a lecture by Professor David Crownfield. A third person thought that the true purpose of sports broadcasts was to put people to sleep. A visiting British lecturer, BBC reporter Bernard Mayes, stated that the dependence of American commercial television on advertising revenue worked to the detriment of high quality programming. Yet, shortly after Mr. Mayes's appearance, CBS reporter Don Webster pointed to the commercial success of programs such as "60 Minutes". Two months later, in early 1977, a video beam television was installed in the Keyhole Room of the Maucker Union. This television, which cost about $3000, featured a four by five foot screen. Union administrators hoped that students would organize social events, such as Olympics or Super Bowl parties, around the new set. The first major event centered on that television set was the showing of the series "Roots".

Cable television came back into focus again in 1977 when Bill Riley, from Hawkeye Cablevision in Des Moines, spoke to a broadcasting class on the history and strengths of this service. In November 1978 the matter of allowing a cable franchise, Cablevision, to operate in Cedar Falls was put to the voters. Two UNI faculty members, Barbara Lounsberry and Joe Marchesani, served on the local Cable Commission and painted a very rosy picture for the prospects of cable television in Cedar Falls. They stated that there would be twelve channels, including a local access channel, instead of the existing four broadcast channels. There would be connections to all schools, including UNI. If the issue passed, UNI dormitory rooms would be connected by fall 1979. The cost to subscribers would be $7.50 per month, with an additional $8 per month charge for Home Box Office. Cedar Falls voters passed the measure by a 3-1 majority. In the two precincts populated primarily by UNI students, the margin was over 10-1.

Campus cable installation proceeded very slowly as university officials and the cable company negotiated terms for wiring the residence halls. Indeed, Cedar Falls residential installation also made slow progress: by January 1981, only about a third of Cedar Falls was wired. Nonetheless, Professor Lounsberry maintained her positive attitude about the prospects. At that same time, Professor Marchesani was waiting to produce UNI-related programming for the local access channel, but he thought that any such work, which would require funding, was at least a year away. It was not until late January 1982 that the campus was connected to cable. Professor Robert Hardman said that this was a milestone along the road to a completely wired campus. But that initial connection was meant to serve only educational programming purposes. Dormitory rooms were still not wired.

A decade passed without significant progress toward installing cable in the residence halls. The capital outlay for the initial wiring seemed to be the most important obstacle. Another obstacle seemed to be that the university wanted more educational access than the cable company, TCI of Northern Iowa, wished to give. There might also have been an undercurrent of thought among the administration that cable access in residence halls would undermine students' study habits. There seemed to be a prospect for installation in the fall of 1991, but that deadline passed. The next opportunity was the fall of 1994. Residence on the Hill had cable when it opened in the spring of 1993, because coaxial cable had been installed during its construction. By December 1993, contracts for providing cable television in the dormitories were under consideration. Under terms of the contract, installation would be completed by August 1994. The $7.50 monthly fee for the service would be added to room and board charges. For this fee, students would receive the basic and expanded basic packages of service, but not the premium packages.

In a February 1994 article in the Northern Iowan, student Bradley Schaufenbuel made the forward-thinking case that cable access did not need to be put into a dichotomy of education versus entertainment. He asked all parties to consider cable television as a means of digital communication:

Imagine plugging the same cable that brings you Beavis and Butthead to your television into your personal computer and having the vast resources of the "information highway" instantly at your fingertips.

After a slight delay caused by slow electronic equipment delivery, cable service was available in residence halls on September 1, 1994. Students would receive thirty-eight channels in the basic and basic expanded packages. Pay-Per-View would be available as a separately billed service. HBO, Cinemax, and Showtime were not available. Northern Iowa Student Government President Beth Krueger noted that the University of Iowa and Iowa State University had had cable service for many years. She said, "UNI finally enters the modern world." It had indeed been a long, fifteen year wait.

Broadcast television and educational programming had, of course, continued during the long wait for cable television. Students had a variety of reactions to controversial shows such as "Soap" and "Saturday Night Live". Many students and alumni around the state enjoyed the first live broadcast of a UNI football game on September 9, 1978, when the Panthers played Youngstown State. Even though a strong Youngstown State team defeated the Panthers, ABC television provided an opportunity to show off the new UNI-Dome to a wider audience. Students enjoyed soap operas, though most admitted that the programs were trash and a waste of time. Even so, many students did not want to miss the wedding of Luke and Laura on "General Hospital", the most popular daytime soap opera of that time. Others were steady viewers of game shows such as "Jeopardy".

Some questioned the message and motives of televangelists. At least one Northern Iowan columnist found that television was a last resort when he had no money to do anything else. Other columnists, such as Jill Funcke, made fun of the shows that she watched, such as "The Brady Bunch". But just about all admitted that they were firmly hooked.

On the educational side, the university hosted conferences on the effects of television on young people. Most conferences seemed to conclude that television could be both beneficial and harmful, but that in any case, parents needed to monitor what their children were watching. And faculty members such as Joan Duea provided valuable consultation to programs such as the public television children's program "3-2-1 Contact". Iowa Public Television offered an increasingly impressive array of college credit courses, though it is not clear how many UNI students took those courses. On campus, Professor John Eiklor, a master teacher in the Department of History, offered memorable courses, taught partly on television, in the humanities. Professor Eiklor said:

Most students who have taken the course really come alive in it . . . Their response has been keen in class discussion especially.

A number of students and faculty even appeared on national television. Professor Jayne Gackenbach appeared on the "Phil Donahue Show" to talk about lucid dreaming in 1987. Student Brad Williams appeared on "Jeopardy" in 1990.

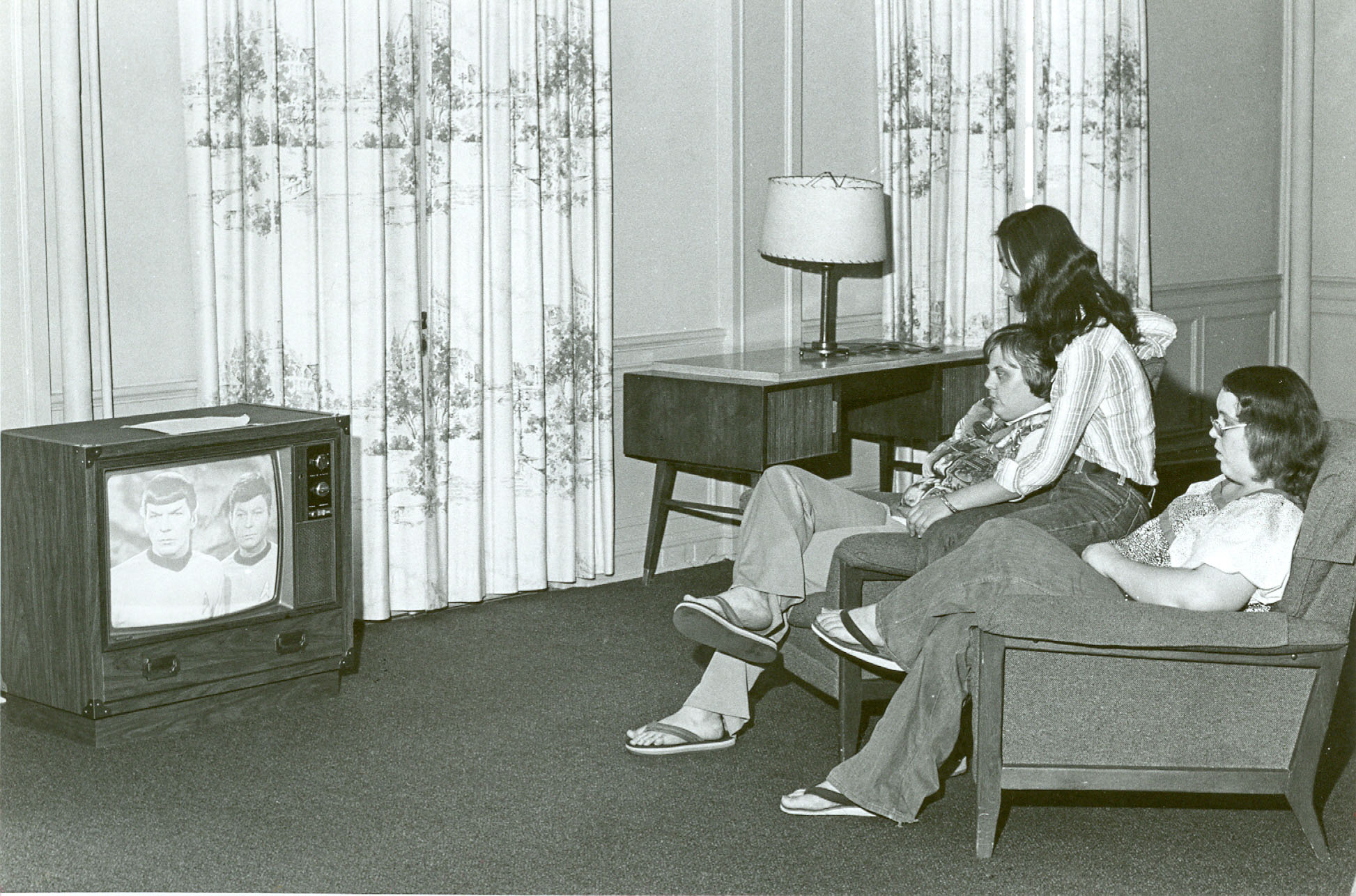

Professor Donna Thompson appeared on "Good Morning America" to discuss playground safety. Occasionally, television personalities spoke on campus in appearances that were both entertaining and informative. For example, James Doohan and Nichelle Nichols, both from "Star Trek", gave presentations. Larry Linville, who played Frank Burns on "MASH", was also a featured speaker. And Ruth Warrick, from soap opera favorite "All My Children", spoke in 1990.

Cable and Much, Much More, 1994-2014

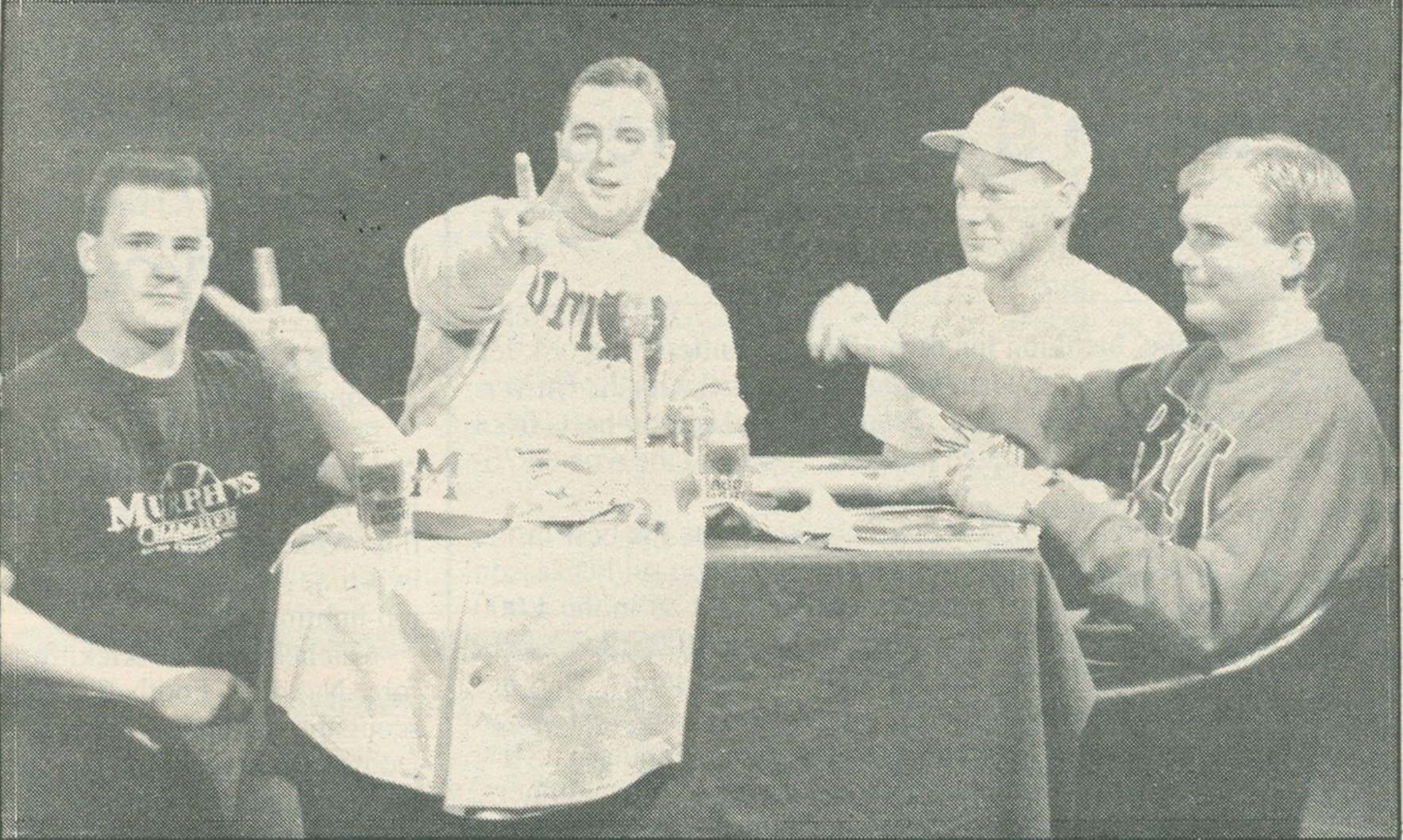

Sports continued to be a favorite among UNI students. As an outgrowth of that interest, four students in Professor Robert Snyder's sportscasting class put together a public access channel show called "Sports Junkies" in 1992. This show was an irreverent and informal take-off on more established sports talk shows. The format was four guys sitting at a table and talking sports. The show was suspended after several months, and then dropped for awhile, due to complaints about language and a lack of professional production values. Some believed that this was a case of censorship, but the university maintained that it, as the producer, had the right to cancel the show for good cause. The show came back a year later under tighter control. It soon attracted a cult following. One show in December 1994 used a new remote mobile television van to originate a live production in the UNI-Dome. By 1995 Professor Snyder could say:

Sports Junkies has become such a great learning experience for students that for the first time this semester people have had to be turned away from working on the show. There are only so many positions to fill.

Later that year the program produced a live show from Young Ice Arena in Waterloo. When "Sports Junkies" originated a live production, they encouraged viewers to call in. Overall, "Sports Junkies" proved to be a learning experience for everyone involved: not just for four guys wearing baseball caps, but for the university and the cable company as well. The local access channel made it possible for just about anyone with a little bit of video equipment to put a show on the air and to attract a surprising audience.

In the fall of 1996, UNI-TV became available. Richard Varn was the supervisor; Wendy Aldrich, Tracy Fellmet, and Ryan Dotson were the station managers. UNI-TV consisted of four channels:

- Panther Bulletin Board--campus events, schedules, and messages

- SCOLA--international newscasts

- Educational programming channel

- Student-produced programming channel

The student-produced channel included a live newscast that was part of video practicum and video production classes. The first of these newscasts took place on September 12, 1996. Kim Wilgenbusch and Ryan Dotson produced the show. Wendy Aldrich and Jason Reid served as anchors. Professor J. C. Turner was the show's advisor. Students in those classes were grateful to have the experiential learning opportunity to put their skills to work in an actual production.

During the fifteen year wait for cable television in the residence halls, students had found some comfort in renting or borrowing videocassettes of classic and relatively current movies. That, however, required trips to the video store to select and then return cassettes. With the advent of cable service, students found a wide range of constantly available and entertaining programming at their fingertips. MTV was a great, early favorite. Students enjoyed reruns of "MacGyver", "Dukes of Hazzard", and "Scooby-Doo". Some enjoyed the conservative views of FOX-TV. Others enjoyed a wide range of sports broadcasts, especially from WGN in Chicago and TBS in Atlanta. There was also a broad array of talk shows: Ricki Lake, Sally Jessy Raphael, Jenny Jones, Leeza, and Montel Williams. In 1997, Northern Iowan columnist Faith Kopecky wrote that she would take Looney Tunes cartoons any day over the talk shows.

In early 1997 Professor Leigh Zeitz speculated that the Internet was beginning to be a rival for television. This was a foreshadowing of the way in which certain technologies would eventually blend and become accessible in a single electronic device. Students were also noticing that television, with its increasingly seamy subject matter as well as the non-stop news and details of sex scandals at the highest level of government, were coming very close to the edge of what should be broadcast on public airwaves. In 1998 Professor J. C. Turner stated that continuing programming of this nature desensitized the public to unacceptable and dangerous behavior.

Still, some things continued along familiar routes. In 1999, the UNI Symphony Orchestra performed "Halloween Hoopla" on the Iowa Public Broadcasting Network. In 2000, Professor Roy Behrens and a group of students appeared on that network's "Living in Iowa" series. And just about every year in late January a Northern Iowan columnist would be sure to write about Super Bowl commercials.

In 2000, the A. C. Nielsen Company stated that the average American watched television three hours and forty-six minutes daily. Partly in reaction to that startling figure, an international Turn Off TV week was organized. People were urged to turn off their television for the week of April 24-30, 2000. On the UNI campus, student Jonathan Fretheim led that effort. He stated, "I want people to be more conscientious and critical about the types and amounts of media they consume." A panel discussion would consider some of the bad influences of television on American culture including the fostering of personal isolation, the promotion of consumerism, and the glamorization of dangerous cultural norms. The effort was renewed the following year. It is, however, unclear if these efforts actually made anyone turn off his or her television.

The appearance of many "reality" shows in 2003 was a trend that some students found annoying. Patterned after MTV's "The Real World", these shows did not seem to be close to any reality that most people experienced. Nonetheless, reality programming continued to be popular for many years thereafter. In January 2004, Northern Iowan columnist Steve Athay took a particularly harsh look at television. He blamed the mesmerizing box for weight gain, physical and mental laziness, and uncivil behavior that resulted, ultimately, in a kind of antisocial brainwashing. He wrote, "We've relaxed our minds and in doing so opened it up to influences we normally would not have succumbed to." While that statement could use a bit of grammatical polishing, the implication is quite clear.

But, as usual, whenever television received a round of particularly harsh criticism, something good came along. In March 2004, Professor Mark Grey, director of the university's New Iowans program, assisted with the production of a seven-hour miniseries on Iowa immigrants. The miniseries was shown on IPBN in late March and early April. Professor Grey said that "the program strives to help build a feeling of collectivism between native Iowans and refugees and immigrants who are new to the state." He believed that it was critical for Iowans to understand the important role that new immigrants would play in the state's future. "America's Lost Landscape: the Tallgrass Prairie" was another fine program with which the university was associated. Drawing on the expertise of Professor Daryl Smith and the narration skills of Northern University High School graduate Annabeth Gish, this award-winning program premiered in late 2004.

In 2008, Northern Iowa Student Government began to tape its meetings. Those tapes were then aired on local cable channels. NISG Vice President Clarence Lobdell hoped that students would take this opportunity to become better informed about campus issues and to make student government more responsive. In 2009, electronic media students tried their hand at producing a new kind of local news programming. Instructor Nathan Epley said that the series of four 5-minute shows would be aimed at "the audience that is on the Internet." The four program subject areas were:

- "Addictive Alternative", aimed at the area music scene;

- "NetShock", devoted to new technologies;

- "Rendered Out", an entertainment news show; and

- "UpVote.TV", on popular or controversial Internet stories.

This imaginative kind of programming reflected the rapidly changing world of television. What would have seemed strange and overly specialized a few years earlier, now seemed normal, appropriate, and on-target. Local and cable television programming, as well as Internet blogs and Podcasting, attempted to reach highly specific audiences with short attention spans.

By 2014, broadcast channels had long since faded away from the consciousness of most students. If they watched regular television programming at all, they seemed to be much more interested in cable channels associated with quite focused content, such as sports or news. But even cable television seems destined to leave campus soon. Department of Residence administrators say the students now tend to use YouTube, Netflix, or similar services for most of their viewing. On-demand service of one sort or another has just about replaced the old habit of waiting to watch a particular program scheduled for a particular time. Also, social media activities now consume a great deal of students' time. Cable television access will likely be removed from residence halls in the near future.

Summary

Television has been available on the University of Northern Iowa campus for over sixty years. In the years before the advent of practical broadcast reception in the Waterloo/Cedar Falls area, the school made significant advances in the production of educational programming, largely under the direction of Herbert Hake. When local network affiliates began broadcasts in late 1953, students quickly came to enjoy watching television. But, since access to a television set was limited to only a few places on campus, television viewing was not a strong rival to more productive activities, such as study. Those early years of programming tended to follow existing models of journalism; there was a fair amount of fluffy, light entertainment, but there was also a great deal of serious news and public affairs content.

Since early broadcast days, television has been the object of continued, harsh criticism as a time-waster and even a source of moral corruption. It was an easy target. Like many technologies, television offered the prospect of being an extraordinarily valuable educational tool. Indeed, over the years, UNI faculty and staff produced an impressive body of work in the television medium. But television also could be used for less than productive objectives. Few people would quarrel with the premise that television can be a source of pleasant, relaxing entertainment. Not every moment of a person's life needs to be devoted to serious work or study. But did the entertainment aspect of television go too far on both the silly and the corrupting fringes? Did television tend to sink to the level of the lowest common denominator among its viewing audience? Did television simply reflect existing societal values? Or did it actually help to lead public values in a bad direction?

Precise answers to questions like this are hard to determine. Isolating cause from effect is probably a fruitless exercise. What is clear, though, is that television has had an enormous effect on American life in the last sixty years. The campus of the University of Northern Iowa is no exception. When broadcast television arrived on campus, it was an attractive novelty. There were very few television sets, so watching television was almost necessarily a social occasion. Over the next thirty years, access to television became much more widespread. Many students had their own television sets in their rooms. However, the array of programming sources changed little over that period. Most people were limited to CBS, NBC, ABC, and IPTV broadcast channels. Videocassettes improved that situation a little. Cable television service opened that door wide. Students had dozens of television viewing options. Local access channels made it possible for them even to create their own television shows. Accessible Internet service initially seemed to operate on its own track, but in recent years the lines between television and Internet service have become blurred. Television programs themselves, as well as things that in earlier years might have become television programs, are now available via the Internet on a hand-held device.

It is hard to say where television might be headed on the University of Northern Iowa campus. With the possible exception of programs such as sports events, the days of sitting down together with friends to watch television might be over. Even these special occasions, which hearken back to the early days of television viewing, tend to take place in a sports bar where televisions are only one of the competing attractions. Convenience will certainly be a part of the future of television on campus. With busy personal and class schedules, most students will watch only what they want to watch and only at a time that is good for them. Hand-held devices with Internet access make this possible. For college students, time spent actually watching a television program will almost certainly continue to decline. Checking social media might well have replaced hours of mindless television viewing.

Perhaps the safest thing to say is that the old idea of television as a separate and distinct entertainment and public affairs medium will likely continue to merge with other media formats such as radio, film, computers, telephones, and things not yet imagined.

If we had access to the prophet/editorial writer from the 1892 College Eye who was cited in the introduction to this essay, perhaps he would be able to give us a clearer picture of what the future of television might be.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, with research assistance by Student Assistant Mackenzi Brophy and scanning by Library Assistant Joy Lynn, August 2014; last updated, February 9, 2015 (GP); photos updated and citations added by Graduate Assistant Eileen Gavin, May 2, 2025