Library facilities and service at UNI, 1876-2004

Introduction

The Library of the University of Northern Iowa has come a long way since 1876. It began as a tiny collection of books left over from an orphans' home and has grown to a collection of about one million volumes. The original staff of part-time students, whose main tasks were checking out and shelving books, has grown into a group of about sixty experienced and well-trained library specialists. The community that the Library serves has grown from twenty-seven students and four faculty to over thirteen thousand students and over six hundred faculty. The curriculum, once focused exclusively on teacher training for students who came to campus for only a term or two, now attempts to meet the needs of many undergraduate and master's degree curricula as well as two doctoral programs. Its budget has grown from absolutely nothing to over $5.7 million. Library facilities have grown from a couple of classroom shelves into a spacious, well-equipped building.

While these simple contrasts are impressive, there is considerably more to the history of UNI library services. Growth, development, and changes in administrative organization, staff, services, and facilities do not happen in a vacuum. They arise at particular times and places for particular reasons. This brief history attempts to look at some of the high points in the history of library service at UNI. It will look at the facilities, leaders, improvements, programs, services, and developments that have characterized over 125 years of innovative and responsive service to the UNI community.

Beginnings--1876-1886

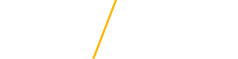

The campus of the Iowa State Normal School, now the University of Northern Iowa, was originally the site of the Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home. This institution, which served as a home for orphans of Civil War soldiers and sailors, was located on a forty acre site donated by the citizens of Cedar Falls to acknowledge their debt to those who lost their lives as a result of the war. That forty acre site, then far outside the Cedar Falls city limits, was bounded roughly by 23rd Street on the north, College Street on the east, 27th Street (which then ran through campus) on the south, and a line running north and south through the area where the Campanile now stands

By 1876 the orphans were growing up and leaving the home, so the state decided to close the Cedar Falls branch and consolidate operations at the orphans' home in Davenport. The Orphans' Home Board, when it transferred management of the campus to the newly-formed Iowa State Normal School Board in the summer of 1876, took most of the moveable property to Davenport. This included most of the Orphans' Home library. In 1875 the Orphans' Home Board had reported that this library consisted of a good-sized collection of one thousand volumes of poetry, biography, fiction, history, and travel, suitable for children. The Board noted that the cost of the collection had been about $900.

Consequently, the origins of library service at the University of Northern Iowa were decidedly modest. When the Normal School Board took charge of the campus in the summer of 1876, only a small, tattered collection of children's books remained on the premises. The General Assembly made no provision for library facilities or material for the new school. Professor David Sands Wright recounts in his anecdotal history of the school, Fifty Years at the Teachers College, that he and another faculty member, Moses Willard Bartlett, sorted about a dozen good titles from the "old, soiled, dogseared, microbe-infected" remnants of the orphans' collection and sent the rest to the Reform School at Mitchellville. The few good titles--including Uncle Tom's Cabin, Robinson Crusoe, The Swiss Family Robinson, and Pilgrim's Progress--filled less than one shelf in a ten by twelve room in the original Orphans' Home building, later called Central Hall.

The Iowa General Assembly made no appropriation for library material for either the first (1876-1878) or second (1878-1880) biennium of the Normal School's operation. Professors Wright and Bartlett seemed to have continued in their role as unofficial librarians. In early 1878 they are reported as being engaged in numbering, arranging, and sorting the small collection. Later in 1878 faculty members put together a Lecture Course in which they spoke and gave demonstrations to raise money for library reference books. The Normal School Board, in an understated tone, noted in its 1880 report that "The efficiency of the school would be greatly increased by the addition" of library facilities. During that time and for a number of years thereafter, students and faculty relied heavily on the generosity of the school's first principal, James Cleland Gilchrist, who made his substantial private book collection available to them.

The General Assembly did provide $1000 for library material and apparatus for the third (1880-1882) biennium. Thereafter, state appropriations tended to include at least some provision for the development of library facilities and collections.

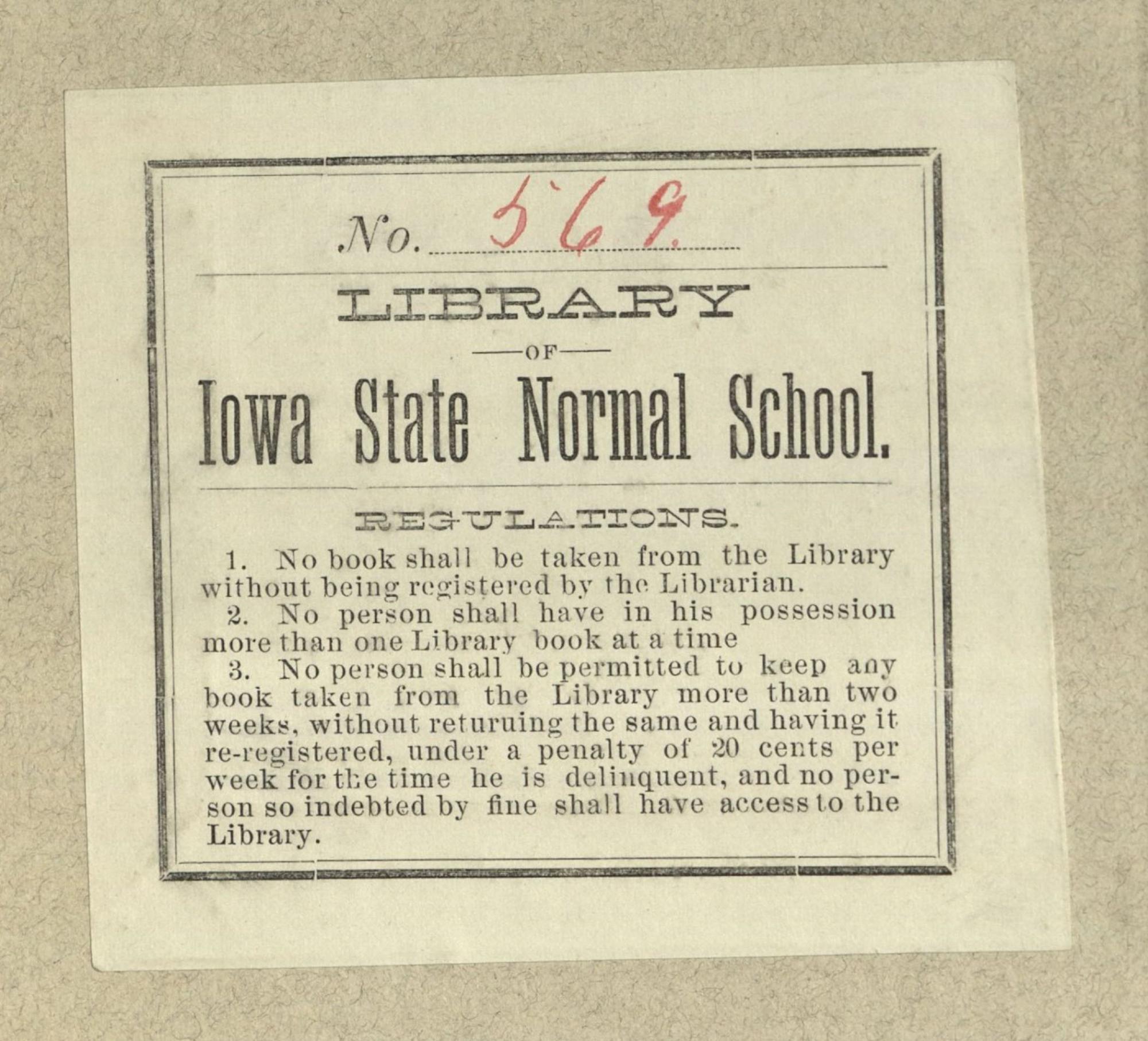

Though the resources were quite limited, students of the Normal School took pride in their library. In December 1880 the student newspaper announced that "Our library is now arranged, the books classified and catalogued. . . Library rules are exceedingly strict . . . ." By December 1881, each student received a list of all books in the library, arranged by author, subject, and shelf number. In early 1882 the student newspaper noted that the library collection had been enriched by the addition of a dozen books on temperance, then, as now, a matter of great interest and significance to students. The Board noted later in 1882 that a "small working library has been placed in suitable cases, labeled, numbered, indexed, and catalogued . . . The library is open several hours each day in the care of a [student] librarian . . . ." Students themselves contributed $268, a significant sum for the time, toward the maintenance and staffing of the library. In 1882, Sara M. Riggs, a recent Normal School graduate and later a long-time history faculty member, is noted in the school catalogue as serving as "Librarian and Secretary to the Faculty". It is unclear at this time exactly what Sarah Riggs' duties were, but the position seems to have lasted only one year.

With the completion of South Hall (later known as Old Gilchrist Hall) in 1883, the library collection was moved to a small room on the second floor of that building.

Despite the new location for the library, in February 1884, an editorial in the student newspaper cited the library as its first priority for improvement: "We need a better library and a better index of the one we already have." The article went on to state that the current index, or catalogue, was so poor that a student might as well simply look through the entire collection to find what he or she wanted.

When the collection outgrew the single room that it occupied in South Hall, a partition was removed to double the space. But in 1886 the overall strength of the school's library resources was greatly diminished when Principal Gilchrist resigned and took his five hundred volume personal collection with him. In terms of quantity, the Normal School collection was cut by about one-fourth. But the qualitative loss was more severe. By the time that he left Cedar Falls, Principal Gilchrist had been involved in teacher training for thirty years. Consequently, his collection was especially strong in the field of pedagogy, or education, as it is now called. Since the curriculum of the Normal School was devoted exclusively to the training of teachers, the loss of access to Principal Gilchrist's collection was devastating.

Sidelight: Many years later portions of Principal Gilchrist's collection found their way back to Cedar Falls. After Principal Gilchrist's death in 1897, members of his family donated some of his books to the Normal School as a memorial to his pioneer service at the institution. Some of these books, with Normal School bookplates and Principal Gilchrist's signature, are available for inspection and use in Rod Library Special Collections.

The Early Seerley Years, 1886-1907

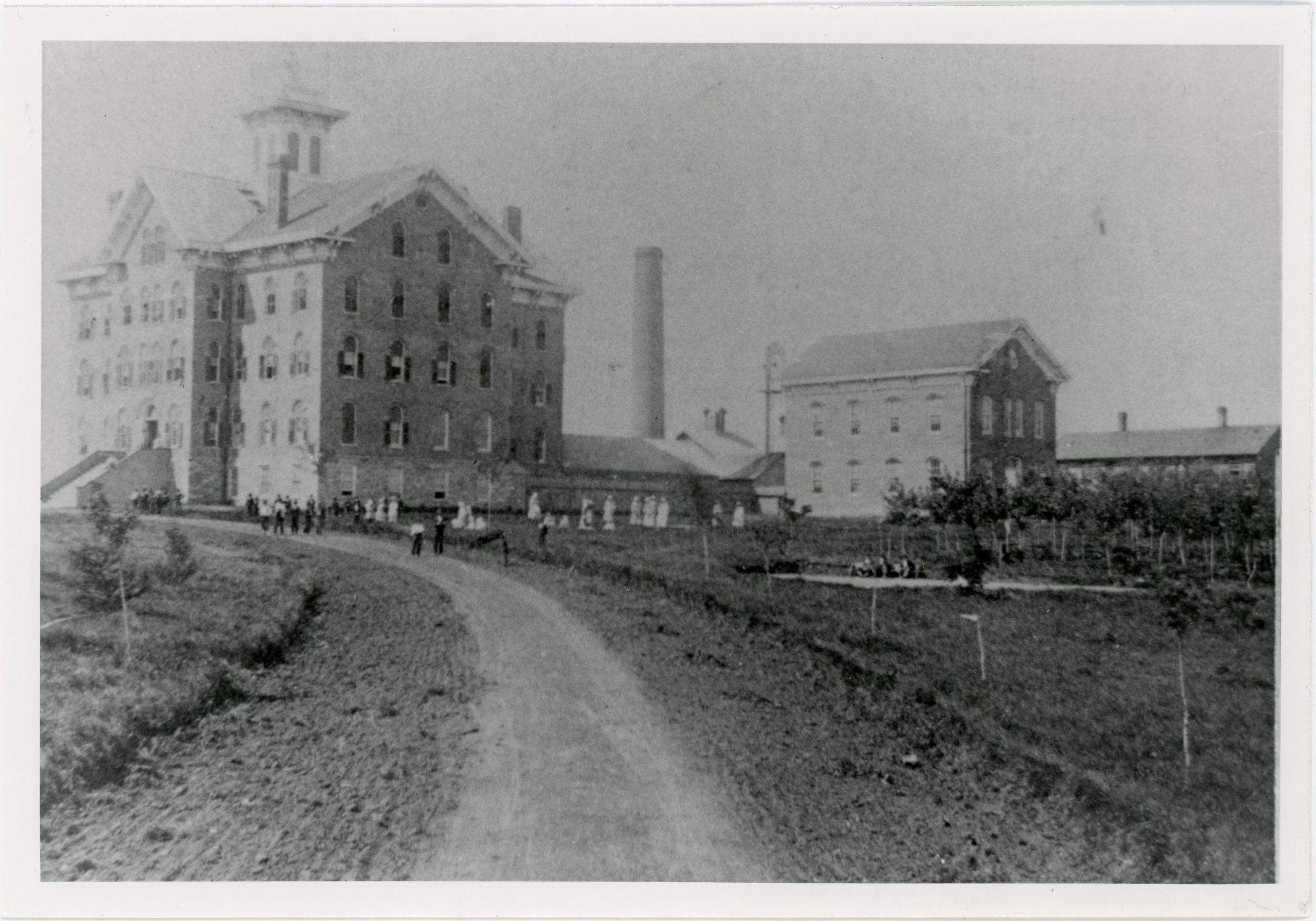

Homer Horatio Seerley inherited this difficult situation when he became the second principal of the Normal School in 1886. Though faced with the discouraging reality of a 1200 volume collection to serve about three hundred students, Principal Seerley had a grand vision for the role of a library in an institution of higher learning. In his first report to the Normal School's Board of Directors he stated that "a good library is a necessity . . . it is a requisite. It should come before teachers and students." He went on to say, "A school to do a great educational work must have an extensive, well chosen library, a well-supported reading room containing current magazines and literature, and a member of the faculty as librarian, whose chief work will consist in teaching students how to use books."

Principal Seerley was well ahead of his contemporaries in expressing these views. Few college presidents in 1887 were so far-sighted that they conceived of a library as anything more than a random collection of books shelved in an extra classroom. Yet even at this early date, Principal Seerley, the head of a small Midwestern normal school, saw the need for:

- a carefully-selected collection;

- located in an appropriate physical setting;

- and attended by a professional librarian who could provide reference service and bibliographic instruction.

Principal Seerley's vision of a library is as meaningful today as it was well over one hundred years ago.

The General Assembly came to respect the requests that President Seerley (his title changed from Principal to President in 1888) and the Normal School Board made. Legislators learned that President Seerley and the Board asked for only as much as they believed that the Normal School truly needed.

In 1890 the Board reported that "No part of the school facilities is more highly appreciated by the normal students than the use of the library, and we have asked for only such an amount as will enable us to meet and satisfy their demands." According to a note in the student newspaper in January 1892, students used the collection heavily: "Day after day its pleasant rooms are filled with earnest students who have recognized in the volumes arranged along its shelves, true friends." A nice addition to the library was a noteworthy occasion on campus. For example, later in 1892 the student newspaper was happy to report the acquisition of a new set of the Century Encyclopedia. Of course, the addition of new books raised the question of where to put them. Not long after the Library had acquired the new encyclopedia, the newspaper noted that new books were piled on tables and window sills. The student newspaper regularly featured reviews of new library books in 1893. Also, at least as early as that year, those in charge of library matters had learned the value of periodical literature: the library was sending periodical issues to be bound into annual volumes and student Samuel Smith had made a rack for the newspapers.

The General Assembly responded with enough funding to increase the size of the collection to approximately five thousand volumes by 1894. The exact number of volumes was not known because Normal School students, without professional training, performed all library tasks. Indeed, students were involved in a great deal of the maintenance of campus buildings and services in those days.

The cataloguing and arrangement of the collection were apparently serviceable but rudimentary. In addition to a better catalogue, President Seerley thought that students needed "the counsel, the advice, and the help of a well qualified and experienced person" to serve as a librarian. President Seerley repeatedly requested the hiring of "an expert" to manage the library. In the spring of 1894, the Normal School Board hired Anna Baker at an annual salary of $500 as the first regular staff librarian of the institution. The library was to be open from 7:30 AM until 5 PM Monday through Friday and from 1 PM until 5 PM on Saturday. President Seerley arranged for a student to come in for an hour around noon so that Miss Baker could go to lunch. The new librarian spent a portion of the summer of 1894 becoming acquainted with the Normal School library before she officially began work in September 1894.

Prior to her appointment as librarian, Anna Baker had taught one year and had taken the Kindergarten course at the University of Chicago. When she was hired, she was working as the Bill Clerk in the General Assembly in Des Moines. Despite President Seerley's request for "an expert", Anna Baker had no professional library training prior to starting her work at the Normal School. Yet she quickly and willingly took up her work and became a well-known and respected member of the campus community. The student newspaper notes that she put the collection into better order, created lists of books to suit student needs, and organized classes to help students use the library more effectively. In March 1901 the student newspaper noted that a new series of classes was about to begin: "Students who are not acquainted with Poole's index, the cumulative index of magazines, card catalogues, and the card catalogue of magazines which is brought down to date, will find it to their advantage to investigate these aids to quick, and independent finding of material needed." While the names of the resources and the means of access have changed, the philosophy behind this statement still makes good sense today, even down to the modern appeal to independent, and possibly "life-long" learning. Anna Baker remained in her post until 1907 when she accepted a position at the Los Angeles Public Library.

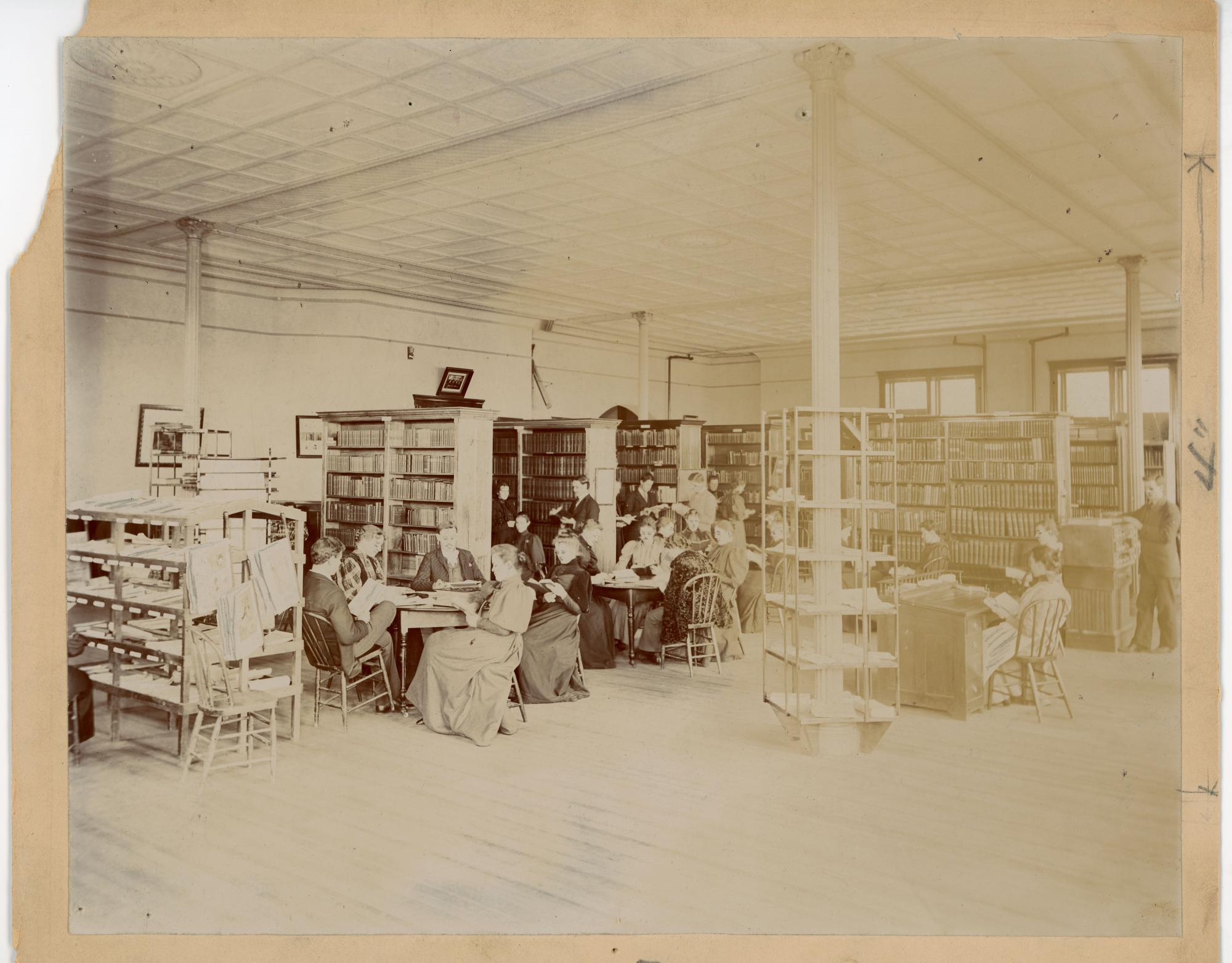

Library facilities also improved significantly at this time. When the new Central Hall (later known as the Administration Building) was completed in 1896, the library collection moved into a much larger space on the first floor of the new building that was furnished with at least the beginnings of appropriate library equipment and apparatus. The new space was a well-lighted room, 71 X 47 feet, with a high ceiling. The library was closed briefly while the collection was moved from Gilchrist Hall.

After the earlier cramped quarters, the new library must indeed have seemed spacious and "in every respect a beautiful and noble" space, as the Directors described it in a report shortly after the move. Student use of the new facility was heavy. The student newspaper was enthusiastic: "Of all the things that make the Normal School student rejoice, perhaps the new library is most highly prized." In a nod to the school's heritage, the library acquired a collection of Civil War era newspapers in 1896. Also in 1896 the library staff was at work on compiling an index to periodical literature, though Poole's Index, a predecessor to the Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature, would be available in the library by 1899. For the winter term of 1896, the first term in the new library location, Anna Baker reported that 5283 items had been loaned. The library even remained open for portion of the Christmas break in 1896 to accommodate students and faculty who stayed in town.

In early 1897, a department for children's books was organized with a start-up collection of eighty-eight books, including the Pansy books, by Louisa May Alcott; the Rollo books by Jacob Abbott, and several books by Charles Coffin. This new department survives today as the Rod Library's Youth Collection. From its earliest days, this department featured a fine collection and annual displays of children's books. It also served as the library for Training School students in Sabin Hall until the Price Laboratory School was built several blocks away from the main campus.

With the collection finally housed in suitable surroundings, President Seerley next asked for both the equipment and expertise to create a complete, standardized catalogue of the collection. First, he requested "a suitable Dewey case and . . . cards for 10,000 volumes, as the books will reach these numbers before long." And second, he wanted to hire an "expert librarian"--to assist and instruct Miss Baker--to develop "a proper classification of the Library." Within a short time, both of these goals were accomplished. Lizzie F. Swan, who worked for two months in 1897 at the substantial salary of $75 per month, finally put the school's library catalogue on a sound foundation. In his 1900 report President Seerley notes as one of the strong signs of progress: "The improvement of the library by the making of a complete card catalogue of subjects and authors."

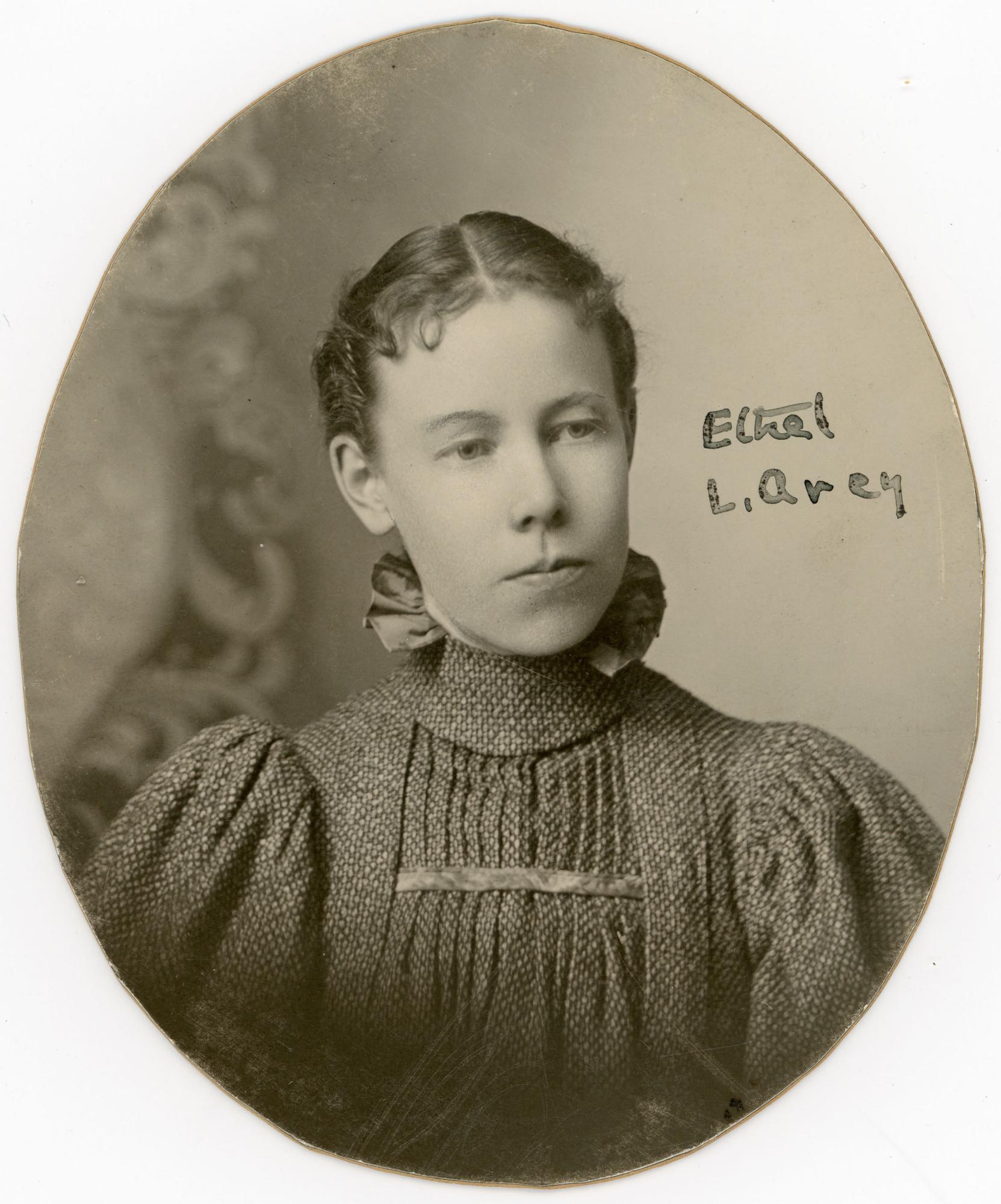

Over the years additional regular staff joined the library. In 1896 Ethel Arey became Assistant Librarian to Miss Baker and also supervised the growing periodicals collection.

Ethel Arey, daughter of Normal School faculty member Melvin F. Arey, was the second member of the Arey family to join the Normal School staff. Her sister Amy Arey, would join the education faculty a few years later. Clara A. Drenning, a librarian at Galena Public Library, followed up on the cataloguing work of Lizzie Swan for several months in the winter term of 1898-1899 and became the first regular staff cataloguer in 1900. Before beginning work at the Normal School, Clara Drenning had acted as a "library organizer" in Savannah, Illinois, as well as in Mason City and Waterloo. Library cataloguing skills must have been as valuable, desirable, and portable around 1900 as are library computer skills a hundred years later. Although Anna Baker and Ethel Arey were employed by the Normal School as librarians before she arrived, Clara Drenning might be said to be the first professionally trained and experienced librarian to join the regular library staff.

Even with these substantial improvements in the library collection, equipment, and staff, President Seerley regarded the facilities in the Administration Building as temporary. He anticipated that the school would shortly need the library space for classrooms and that the library would need more spacious quarters than the Administration Building could provide.

The collection was growing rapidly. There were about 10,000 volumes by 1899 and 14,000 by 1902. Enrollment was approaching 1000, and student use of the library remained strong. Using the devastating example of the 1897 fire that destroyed 25,000 books in the library of the University of Iowa, President Seerley campaigned for a "fire-proof" building to house the burgeoning Normal School collection. What is more, he thought that a new library should be able to house 50,000 or more volumes. Professor William C. Lang, author of the centennial history of UNI, A Century of Leadership and Service, never ceased to be impressed with the audacity of this vision. At a time when only about thirty other college libraries in the world had collections exceeding 50,000 volumes, the head of a small normal school in the Midwest was planning to join that select company.

In 1907, the General Assembly accepted President Seerley's vision; it authorized $175,000 for the construction of a new library building at the Normal School.

Anne Stuart Duncan and the Library in Seerley Hall, 1907-1953

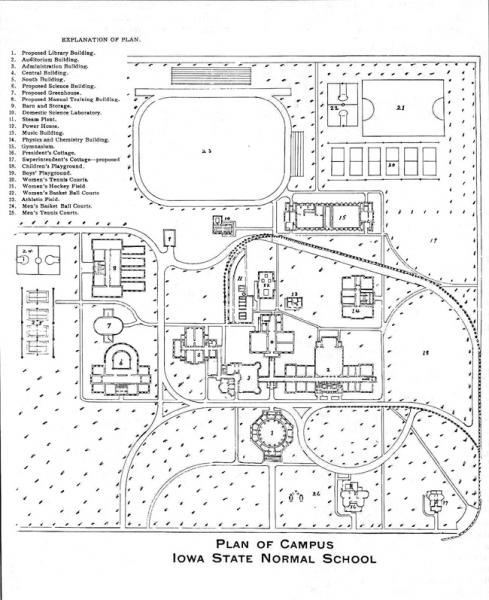

Construction on the new Library, now known as Seerley Hall, began in late 1907, though the cornerstone date is 1908. Normal School officials had had many years to prepare for this event. For several years the Board of Directors had considered an appropriate location for the new building. One early possibility was the area southeast of what is now Lang Hall. This would have featured the building prominently in the school's front yard. What is more, one initial design was for a curious octagonal building with possibly a domed reading room.

But the Board finally settled on what was then the southeast corner of the developing campus quadrangle, noted on the map above as "6" and originally planned as the site for a science building. The new Library and the Auditorium Building (now Lang Hall) would serve as anchors of the campus landscape. The Board authorized President Seerley to tour libraries in the East in October 1906. He returned from his trip with recommendations for a library building that would include space for the school's museum and natural history collections.

The architects for the $175,00 Library were Proudfoot and Bird. The project was financed by the millage tax, a statewide real estate levy. Work progressed slowly, but the new Library opened on May 2, 1911. It rained on moving day, so books had to be carried through the utility tunnel from the Administration Building. At the formal dedication on May 18, 1911, President Seerley said that the opening of the new Library was "the most important improvement at the Teachers College in twenty years." The new building opened with a collection of about 30,000 volumes. The fourth level was occupied by the Museum, and portions of the first level were used as office space.

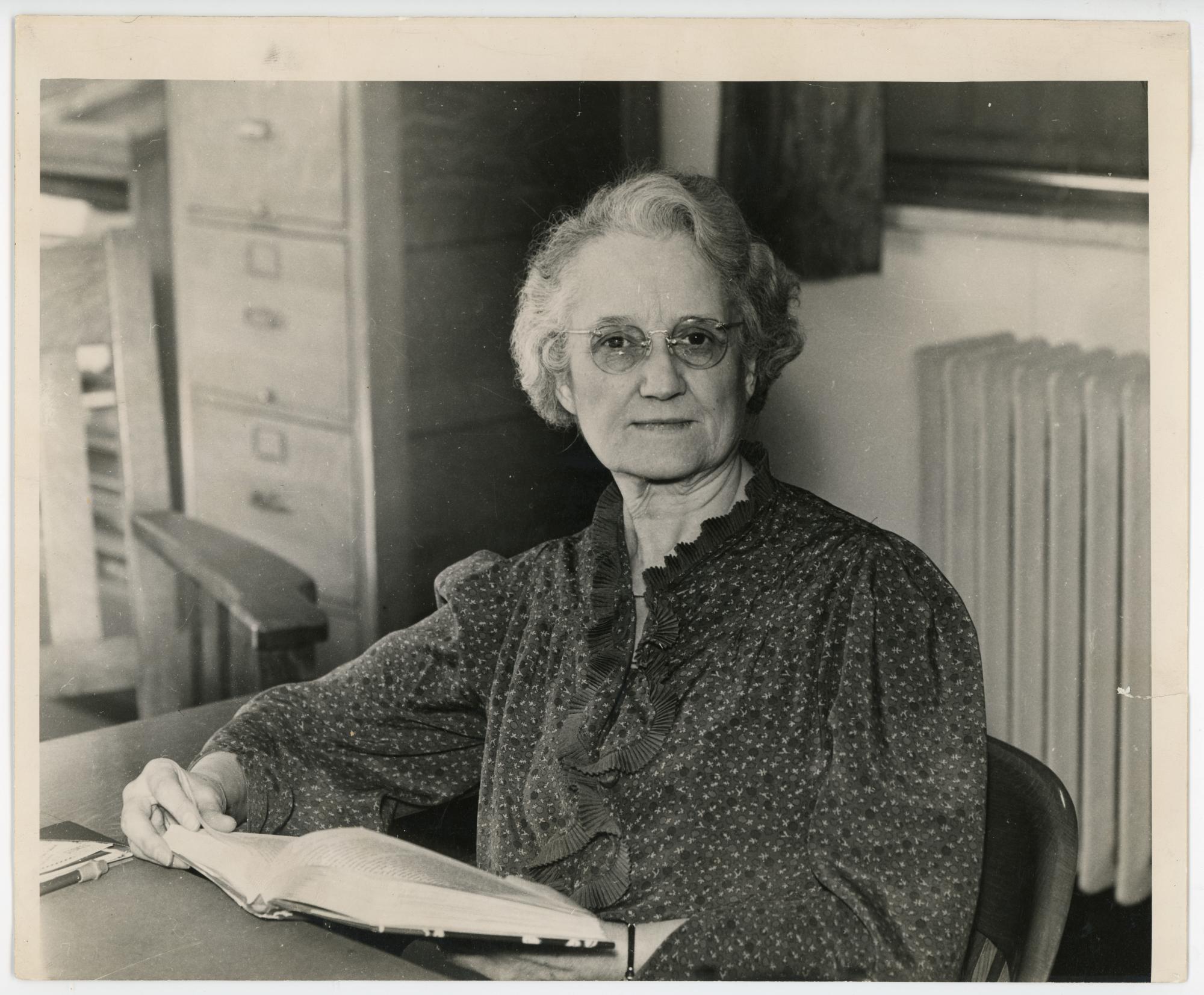

During the time of the building's construction, there were changes in library leadership. Anna Baker resigned in 1907 to become a librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library. Ellen Biscoe succeeded her as librarian in 1907 and served until November 1910. Mary Dunham succeeded Ellen Biscoe in January 1911 and served until 1913, when Anne Stuart Duncan became librarian. Anne Stuart Duncan served until 1943. It was she, more than anyone else, who turned the building into a functioning library and cultural center that served generations of Teachers College students.

Students used the new building heavily. Already by September 1913, just two years after the building opened, President Seerley reported that the Reading Room was so crowded in the afternoons and evenings that there were not enough seats to accommodate students. At about that same time a conflict arose between those who were trying to study and those who were in the Library for other purposes. The conflict between those who were studying and those who were socializing would be a recurrent theme in the student newspapers over the years. There was a rule, if not a vow, of silence in the Library. Students subverted that rule by passing notes around the Reading Room. As early as 1914 the student newspaper, the College Eye, printed a parody of James Whitcomb Riley's "Little Orphan Annie". Could the student writer have been taking some daring liberty with Miss Duncan's first name?

"When you're a-fooling in the library, a-havin' lots of fun,

A-laughing and a-gibbering as if your time had come,

You'd better watch your corners and keep kinder looking out

Er the librarians'll get you if you don't watch out."

The College Eye encouraged students to use the Library only if their work actually required library books. And, in an interesting sidelight on another recurrent library theme, the writer asked students not to take books out of the Library unless they had been properly checked out. This topic would arise repeatedly over the next thirty years, because there apparently was no security system in place other than observation by the busy staff. Not until 1931 were students required to show identification cards in order to check out material.

Anne Stuart Duncan continued Anna Baker's strong interest in teaching students how to use the library. During the 1910s and 1920s there are repeated articles in the student newspaper on using the card catalogue, the reference collection, and periodical indices. Miss Duncan wanted students to be able to conduct research for their classes, to develop good reading habits, and, perhaps, to learn about library operations so that they could manage a school library should their future teaching positions demand such skills. Miss Duncan also informed students about significant library acquisitions. During and after World War I, for example, the Library brought special attention to books on the history, languages, politics, and geography of Europe, as well as the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers. Other Library staff members even provided something like a table of contents service by combing current periodicals and recommending good articles on topics of interest for students to read.

Once the Library was built, President Seerley continued his support of the collections and facilities. In 1921, for example, shelving was added that doubled the capacity of the book storage area. President Seerley's library acquisitions allocations exceeded the total supplies and equipment budget for all of the instructional departments combined.

At the end of World War I, the Board decided that the walls of the Library Reading Room needed to be decorated. Board member E. P. Schoentgen approached William de Leftwich Dodge, a well-known artist from New York, about painting murals for the room. For a fee of $5000, Dodge painted two large 12 X 40 foot allegorical murals, "Education" and "In Memoriam", in his Long Island, New York, studio and shipped them in pieces to Cedar Falls. The first mural, "Education", mounted on the south wall, attempted to portray the value of the Teachers College mission: the training of teachers. The second mural, "In Memoriam", mounted on the north wall, appealed to the very fresh memories of World War I, in which many Teachers College faculty, students, and alumni had served. These two murals were installed in September 1920. The Board and President Seerley were deeply impressed by the quality of the work. The Board immediately commissioned Dodge with a $10,000 fee to produce more murals for the west wall of the reading room. By September 1921, Dodge had completed three new panels: "Agriculture", "The Council of Indians", and "The Commonwealth".

Modern critics may find fault with the style and content of some of the Dodge work. However, the expenditure of such a significant sum on art (almost 9% of what it cost to construct the building) for a state facility in 1920 is impressive. By way of contrast, current Iowa law requires just one half of one per cent of a state building's budget to be spent on art; even that level of expenditure frequently causes outraged reaction from the public. President Seerley saw the Library as a nearly complete educational experience. In addition to the growing book collection and the murals, the Library included sheet music, children's books, museum displays, and prints of artwork. Librarian Anne Stuart Duncan developed the idea of using the lower hall in the Library as an art gallery. There she displayed several hundred reproductions of "the best in art of all nations and all ages" as part of an effort "to bring the treasures of art to every student in school".

Student use of the Library was heavy. Circulation exceeded 20,000 items in the fall 1926 term. Students lobbied first for additional hours on Saturday and later on Sunday. Consequently, in the spring 1927 term, the Library extended its hours until 9:30 PM on Saturdays and from 2 until 5 PM on Sundays. The Library also raised its fine rates at that time: students returning highly-sought reserve books would be fined $.50 per hour. By 1928 the Library collection had grown from about 25,000 volumes when it opened in 1911 to about 90,000 volumes. Four specialized collections, devoted to education, psychology, agriculture, and art and music, were located on the ground floor, as was the children's book collection. The second level, two stories high, contained offices for the twelve staff members and the reading and reference rooms. The two tier bookstacks, projecting west of the building, were located behind the loan desk. The top level was occupied by the Museum.

Miss Duncan said in 1929 that "the Library is most popular in the evening from seven to nine o'clock. But what percentage of the students is there to study is uncertain." The College Eye reporter who interviewed Miss Duncan jokingly suggested that students who entered the Library might be required actually to have a book in front of them. Or perhaps evening hours might be limited to upperclassmen. In 1930 the College Eye recounted an overheard conversation. One student asked a friend if she were going to the Library that night. The friend replied, "No, I have to study tonight." At least until the opening of the Commons in 1933, the Library functioned as an important, though unintended, campus social center. Indeed, a good number of alumni would later claim to have met their future spouses on library dates.

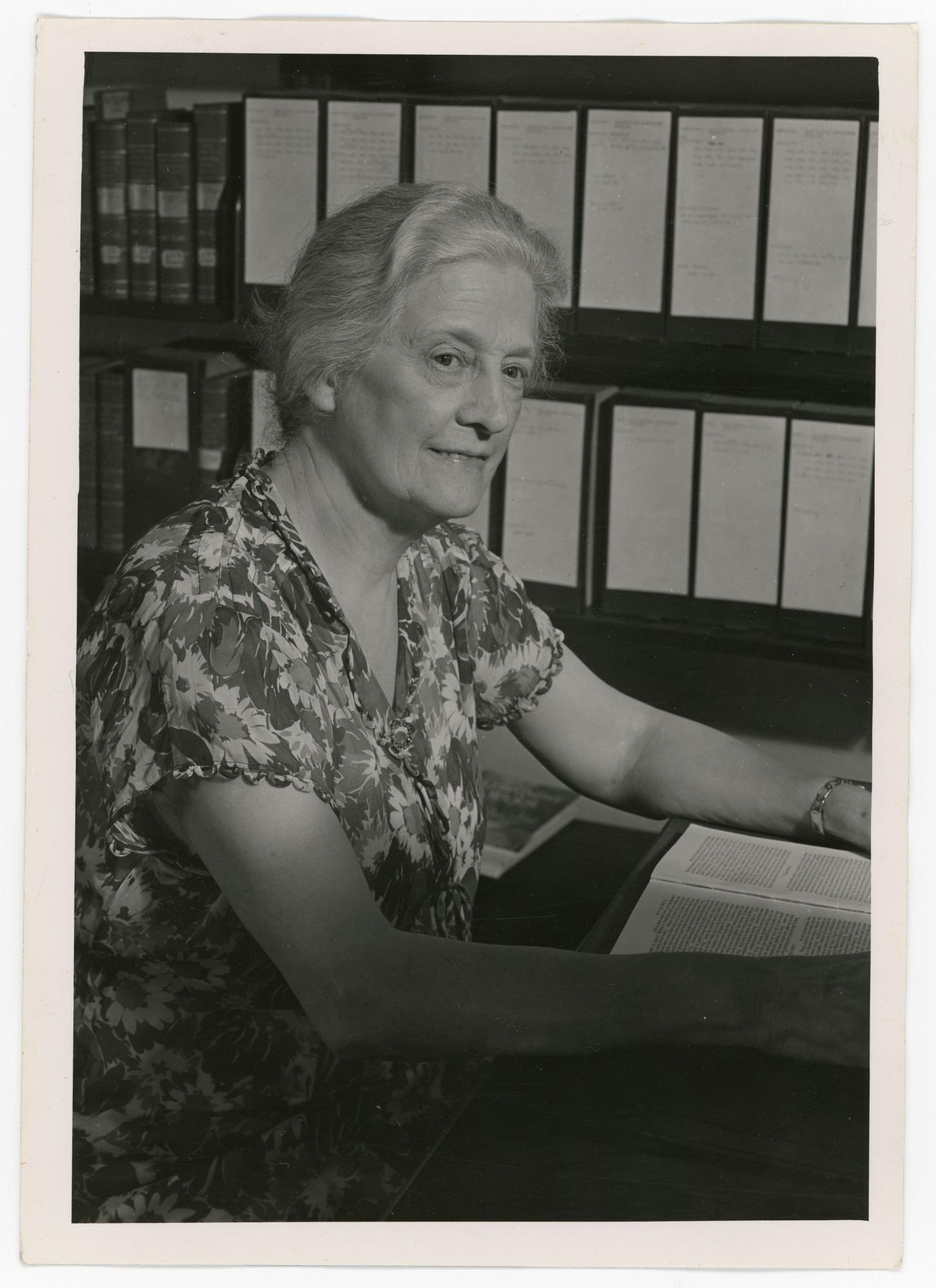

1930 seems to have been a watershed year for the Library. First, in that year Mary Dieterich and Evelyn Mullins began work on the Library staff. They would both remain on the staff, in a number of capacities, for forty years until they retired in 1970.

Also in 1930, the Library established a documents room with about 10,000 volumes of federal, state, and municipal documents. In that same year the Library organized a Browsing Room to promote student leisure reading interests. As a further means of getting students interested in reading, the Library mounted a series of displays that included books on African-American history, detective and mystery fiction, and Western American literature. Several years later the Library began to circulate a bulletin that listed all new books added to the collection.

In 1931 a new women's lounge opened near the north entrance. This was a "suitable place for the young ladies who wish to rest, to chat, or to powder their noses before proceeding to the reading rooms." Also in 1931 the Library Building received new window sashes on the east side. Unfortunately, those windows were decorative and did not open. They provided no ventilation for the reading room, which could be brutally hot during warm weather. Despite the heat, Circulation Librarian Marybelle McClelland noted that 32,000 books were checked out by industrious summer session students in June 1935. The College Eye reported that one enterprising student, Anna Mae Sander, brought her own electric fan to the reading room during the terribly hot summer of 1936.

As early as 1940, with air conditioning available in many theaters, lunch counters, and dimestores, student Katharine Schaffert called for the installation of an air conditioning system in the Library. She concluded her letter to the College Eye: "Our state would harvest rich dividends in greater efficiency in teaching if a little more were invested in the health and welfare of its teachers in summer school." After President Malcolm Price walked through the reading room in the summer of 1941, large electric floor fans were installed.

In the 1930s, the Library staff, especially Reference Librarian Jessie Ferguson, worked hard at creating vertical files of newsclippings and pamphlets on current, local, and special topics that might be difficult to locate in books or periodical indices. These files, created specifically with ISTC students in mind, were invaluable resources for many research assignments. The talented Library staff was also called on to teach classes when a new school library administration course was added to the college curriculum in 1939. Librarians Mary Dieterich, Marybelle McClelland, and Clara Campbell taught that class for the first time in the 1940 summer session. Librarians would continue to teach library science classes on a regular basis even after the Department of Library Science was organized in 1947. And the Head Librarian would serve as head of the Department of Library Science until 1968.

From the time that the Library opened in 1911, the bookstacks had been closed to students. Patrons who wanted a book placed a request at the service desk. Staff members would then fetch the book. As early as 1937 students began to ask if the stacks could be open for browsing. Agitation for open bookstacks grew in the early 1940s until the Library announced that it would indeed open its stacks beginning February 14, 1944. Anne Stuart Duncan resigned as Head Librarian at the end of the 1943 summer term. Marybelle McClelland, who had been on the staff since 1929, replaced her.

In the postwar atmosphere that included many older, serious, and busy students returning to college after military service, the Library sought ways of operating more efficiently and conveniently. In 1945 the horseshoe-shaped reading room desk was replaced by a simpler, more functional desk. Circulation Librarian Evelyn Mullins believed that the new desk would speed up and simplify service. Likewise, the Library installed a book return slot in the north door of the building at this time. Staff members Grace Neff and Helen Schlueter developed a guide to efficient library use called "It's No Secret". This pamphlet later won an award from the H. W. Wilson Company, which specialized in library publications.

By 1946, the Library collection had grown to over 140,000 volumes, considerably beyond President Seerley's envisioned capacity. Daily circulation was over eight hundred books. In 1949 the Library undertook a major book shift involving just about the entire collection, with periodicals going to the first level and education and fiction books going to the second floor. About one-third of the students and faculty--perhaps 1000 people in all--turned out to help with the move. Also in 1949 new steps were installed on the south and east sides of the Library.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s students seemed to become especially aware of the impact of theft and mutilation of library materials. Article after article appeared in the student newspaper on the "destruction plague" that was hitting the Library. Students also complained about noise, library hours, and levels of lighting in portions of the building. These were difficult problems to solve, but the Library did add a library orientation course in 1950 and made a microfilm reader available in 1952. The early 1950s also saw a significant change in library leadership. In 1951 Head Librarian Marybelle McClelland took a leave of absence for study and travel. In her absence, a committee made up of Librarians Mary Dieterich, Margaret Fullerton, and Lauretta McCusker administered the Library. When Marybelle McClelland decided not to return to her position, the college named Donald Olaf Rod to head the Library.

Last Years in Seerley Hall; Donald O. Rod

When Donald Olaf Rod became Head Librarian in 1953, the Library began to undergo a series of changes. Some of these changes were aimed at improving conditions and service in the old building. Other changes anticipated a move into a new building at some point in the foreseeable future.

The Library revamped its reserve procedures for the winter term of 1953-1954 and later added microfilm of the Des Moines Register and the New York Times. Mr. Rod also tightened security measures in 1955 by placing periodicals in plain view of a service desk and by requiring that the periodicals be checked out even for room use. In 1959, to combat the continuing problem of theft, the Library instituted a checkpoint system through which patrons had to pass when they left the building. In 1956 large ceiling exhaust fans were installed over the stacks and the Browsing Collection was re-organized. In 1957 the utilities tunnel that led from the Old Administration Building to the Library was finally filled in. It had been closed due to its weakened condition for some time. Also in 1957, while students could still complain about noise levels in the Library, at least at this point it was the noise of library improvements: a quick survey showed improved lighting, new furniture, upgraded lighting, microfilm, typewriters, and photocopy service.

In 1956 college officials had already begun talking about building a new library and turning the old Library into a classroom building. In July 1958 Mr. Rod stated his case for a new building to the College Eye. He cited statistical evidence. The current Library seated about five hundred students. However, a college with an enrollment of about 3000 students should seat 750-1000 students. Also, the Library staff was having great difficulty in finding space for the one hundred new volumes added to the collection weekly. And he cited aesthetic and efficiency concerns. The high ceiling of the Reading Room wasted valuable space and created a difficult acoustical situation. Mr. Rod hoped to be able to solve these problems in addition to setting up separate rooms for microfilm readers, typewriting, and listening to music. In the fall of 1958, with Laboratory School library operations completely transferred to the new Laboratory School building, Mary Kay Eakin was hired as Youth Librarian with a sharper focus on serving future teachers, rather than schoolchildren.

In 1959 the Youth Collection was expanded, a separate microfilm room was established, and the Government Documents Collection was moved to the third level of the building. In 1961 photocopy service, probably some sort of Thermofax process, became more accessible at the Periodicals Desk at $.15 per copy.

In 1961, with plans for a new Library underway, college officials were considering a new name for the old Library Building, once library services moved to a new location. Registrar Marshall Beard said that it might be appropriate to name the old Library in honor of Homer Seerley. President Seerley's name had already been given to Seerley Hall for Men later a part of Baker Hall) back in 1937, but Mr. Beard believed that a more significant building should bear the Seerley name. In the summer of 1961, the Board of Regents approved the recommendation to name the old Library in honor of President Seerley, as soon as library services ceased there. The name shift actually occurred in January 1964.

As noted earlier, at least as early as 1956, Marshall Beard, who would come to be in charge of campus planning, stated that the college intended to convert Seerley Hall into a classroom building and to build a new library. By 1960 the site for the new library seems to have been settled: it would be between Wright Hall and the East Gymnasium. This site seems to have provoked little controversy at the time. It was clearly located right in the center of the instructional buildings of that day. In retrospect, however, there might be some regret that that particular site was chosen, because it began the process of filling in the pleasant and open green quadrangle that stretched from Lang Hall and Seerley Hall on the east clear back to the West Gymnasium, with the Campanile as an attractive centerpiece. Fortunately, the building was set far enough west to spare the beautiful swamp white oak that now stands in front of the Library.

In spring 1961 the library staff surveyed students to see what they wanted in a new library. In June 1961 the General Assembly appropriated $1.5 million for the new building. By October 1961 plans were well underway. The library was projected to be built in three phases. The architects for the project were Thorson and Brom, of Waterloo, but the college was quite fortunate to have the additional expertise of Mr. Rod, who was trained in architecture as well as library science. Officials hoped that ground could be broken for the new building in spring 1962. The new library would include seating for a thousand students, with individual carrels for many more. It would include small study rooms and listening facilities. Its capacity would be 275,000 volumes, and, perhaps as important as anything else to the students of that day, it would be air-conditioned. This was especially welcome to students and faculty who had spent sweltering spring and summer days in the Seerley Hall Reading Room. It would even include a "Reading Garden", a sunken, recessed area in front of the new building. The building would feature modular construction: that is, regularly-spaced columns and beams, rather than walls, would bear the load. This would enhance the flexibility of the building to respond to changes over the years. The building would include offices and classrooms for the Department of Library Science. Officials hoped that the building would be complete by fall 1963.

Soil tests at the building site got underway in November 1961. The Board of Regents awarded contracts for building construction in September 1962. Henkel Construction Company of Mason City won the general contract; Young Heating Company of Waterloo won the mechanical contract; and See Electric Company of Waterloo won the electrical contract. The building, measuring 235 feet X 127 feet and including about 90,000 square feet of space on three levels, would be similar in design to Russell Hall. The groundbreaking ceremony was held October 8, 1962, and excavation got underway shortly thereafter. Several short strikes involving workers on the project hampered initial progress on the building.

But the labor difficulties were settled, and winter weather cooperated, so that by January 1963 Mr. Rod could say that work was back on schedule. The lower level had been enclosed and work was progressing on the floor of the main level. Before the first phase of the new library was even close to completion, Mr. Rod was sowing the seeds for the next phase of library construction. In June 1963, he said, "The day the new library is ready for use it will be overcrowded." He noted that rapidly growing enrollment and the changing curriculum made it nearly impossible to keep up. The first phase was being constructed to allow for easy expansion to the west. Completion of Phase I was set for April 1964.

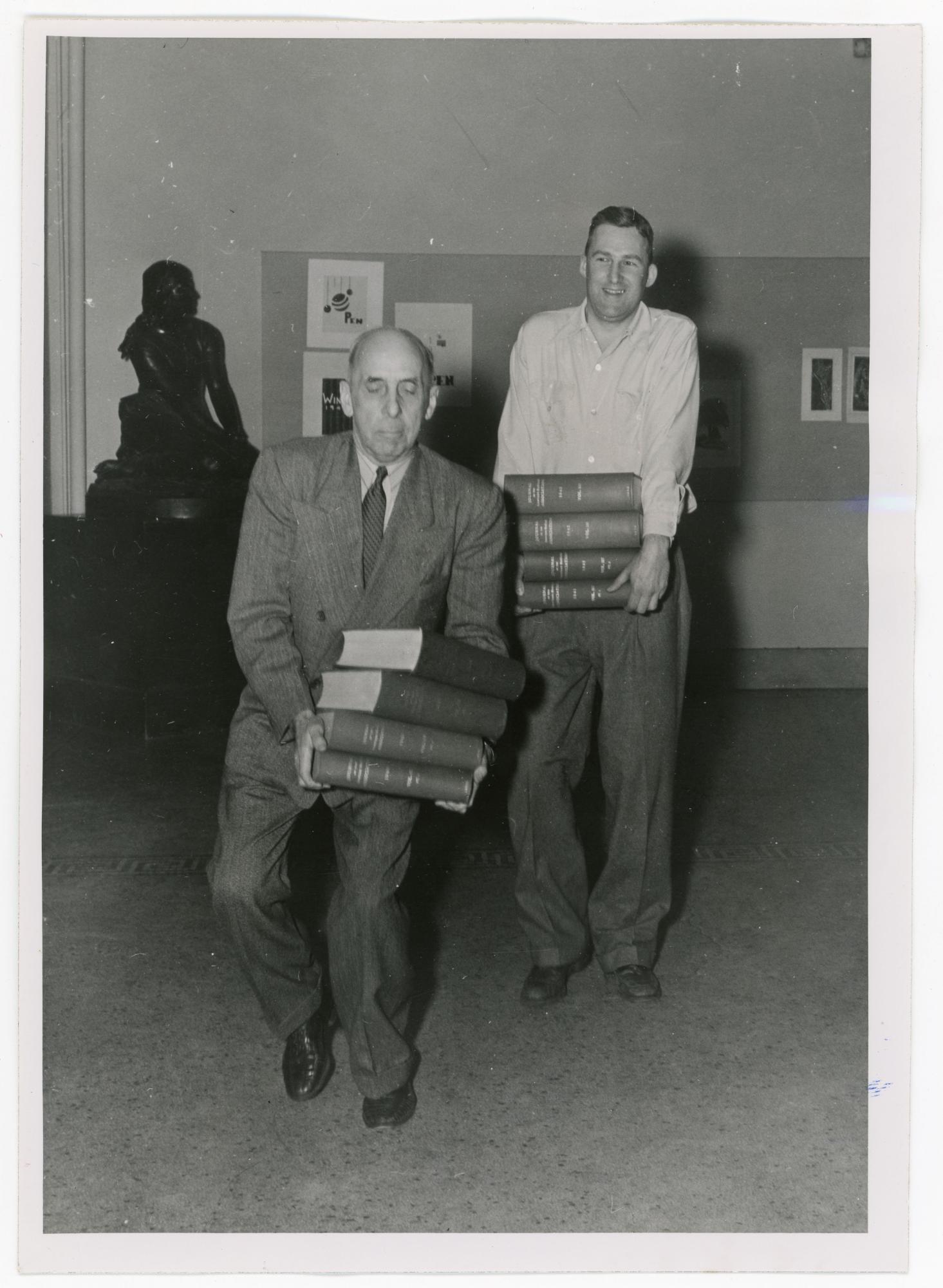

The building was finally completed in July 1964. Library staff and professional movers shifted the 210,000 volume collection from Seerley Hall to the new building in August and early September, so that the building was ready for students on September 14, 1964.

The cost of the building and equipment was about $1.7 million, with $1.5 million from the General Assembly and the remainder from donations and supplementary funds.

The differences between the old building and the new building were striking. Reference Librarian Edward Wagner, who worked in both buildings, recalled that Mr. Rod did his best to improve service in the old building during its last years as a library. Mr. Wagner especially liked the close proximity of the Reference Desk, the Reference Collection, and the card catalogue. But Mr. Wagner also recalled the icy winter wind that whistled through the north door. Clearly, Mr. Rod faced significant obstacles in making the old location work well. The old building was constructed in a style that was characteristic of early twentieth century libraries. Students and faculty were expected to approach the building on a set of wide outdoor steps, enter the building on the first level, and walk up one level on a marble staircase to a large reading and reference room. This room had a soaring ceiling and was lined with bookcases. Readers could try to find a seat at one of the massive, and not especially well-lit, oak tables or seek assistance at the service desk in the middle of the room. It is no exaggeration to find a distinct resemblance between that service desk and a church altar. The scale and atmosphere were impressive, but also daunting. In contrast, the new building was open, well-lit, divided clearly into functional areas, and featured many different styles and arrangements of seating. Several desks provided an assortment of services. The whole building was more comfortable and built on a more human scale. Everything, including the elevator and air-conditioning, was new and attractive.

By the beginning of 1965 just about all of the furniture, equipment, and services, with the notable exception of the music collection, were in place. The library offered photocopy service at ten cents per copy, graduate study rooms, discussion rooms, and a browsing room. About three or four thousand students used the building daily. An open house for the new building, as well as the newly-completed Hagemann Hall, the Regents Dining Center, and the Administration Building (now Gilchrist Hall), was held on October 10, 1965.

One of the first big projects undertaken by the library staff in the new building was the reclassification of the book collections from the Dewey Decimal system to the Library of Congress system. While many still believe that the Dewey system is more user friendly and mnemonic, the Library of Congress system tends to be used more in college and university libraries. Mr. Rod proposed consideration of this switch in October 1965. Work got underway in the summer of 1967. This massive undertaking was projected to be finished by 1970, but portions of the work were not completed until many years after that date. Librarians took the opportunity to weed the collection during this project, in which every single book needed to be handled. In a smaller project undertaken in 1966, the Library began to organize its federal documents according to the US Superintendent of Documents classification scheme. At about the same time the Cataloguing Department undertook another major project: the unification of the card catalogue. Apparently from very early on, the public card catalogue had been divided into two parts: one part included author and title entries and the other part included subject entries. As early as 1963 Reference Librarian Mary Dieterich has suggested that patrons would be better served by a unified catalogue. But not until February 1971 did the library administration decide to integrate the two parts into one sequence of cards. These significant projects were accomplished under the direction of Cataloguing Head Fred Y.-M. Ma.

After moving into the new building, the Library began to expand its hours of operation in response to student requests. Those hours have remained at a level over one hundred hours per week during the fall and spring semesters since that time. Also in response to student requests, the Library prepared a number of special display collections relating to topics of particular interest in the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as ethnic studies, civil rights, environmental studies, and student power. In 1969 the Library added the ERIC microfiche collection as a special help for students who were studying education. Also in 1969 the Library strengthened its role as the semi-official campus art gallery when a small collection of ancient cultural artifacts, to be used in conjunction with Humanities classes, was put on display in the building. In the spring of 1971 the Library offered computer-aided searching, mediated by librarians, of the ERIC database. In 1972 the Library began to develop its Career Collection, under the guidance of Reference Librarians Janice Wieckhorst and Adele Simon, to assist students in their vocational choices.

As early as August 1966, the college asked the Board of Regents for $2 million for Phase II of the library. But it was not until December 1970 that the Regents authorized the university to begin negotiations with an architect for what was by then a $3 million project. In April 1971 the Regents approved the selection of Thorson, Brom, Broshar, Snyder of Waterloo for architectural services. Plans were complete and on display by November 1971. Funding for the project would come from academic revenue bonds authorized by the General Assembly. In October 1972 the Regents approved contracts for the library addition. John G. Miller Construction Company of Waterloo was the general contractor, Young Plumbing and Heating Company of Waterloo was the mechanical contractor, and Paulson Electric Company of Waterloo was the electrical contractor. The addition would add 82,300 square feet to the library, increase seating to about 2100 students, and bring the book capacity up to at least 700,000 volumes. The project would also include some renovation of the existing structure.

Work began on Phase II in March 1973. Essentially, Phase II was a mirror image of Phase I attached to the west side of Phase I. In May, the main entrance to the library was closed for the summer so that alterations could be made. Officials hoped that the addition would be complete by September 1974, but the construction itself and delays in ordering furniture slowed things down. Mr. Rod hoped that he and his staff would spend much of the Christmas 1974 vacation supervising the final touches and moving the collections.

The addition was indeed ready for students in January 1975. It offered greatly expanded bookstacks and study space as well as separate and specially designed quarters for Documents and Maps, Art and Music, and Special Collections and Archives. Also, just in time for the move, the current periodicals collection was arranged into about forty subject areas. This arrangement was meant to benefit students and faculty who wanted to browse recent periodical literature in their areas of particular interest. The student newspaper, the Northern Iowan, raved about the expanded library in an editorial that thanked the General Assembly, the Regents, the administration, and just about everybody else who was responsible for the work. The editorial noted, "Nothing appears to have missed the designers' eyes--aesthetics, acoustics, and comfort are more than abundant in every corner." Well known Iowa author Frederick Manfred was the keynote speaker at the dedication of the addition on May 6, 1976. In a moving and inspiring address, Mr. Manfred talked about the value of books and reading in his life.

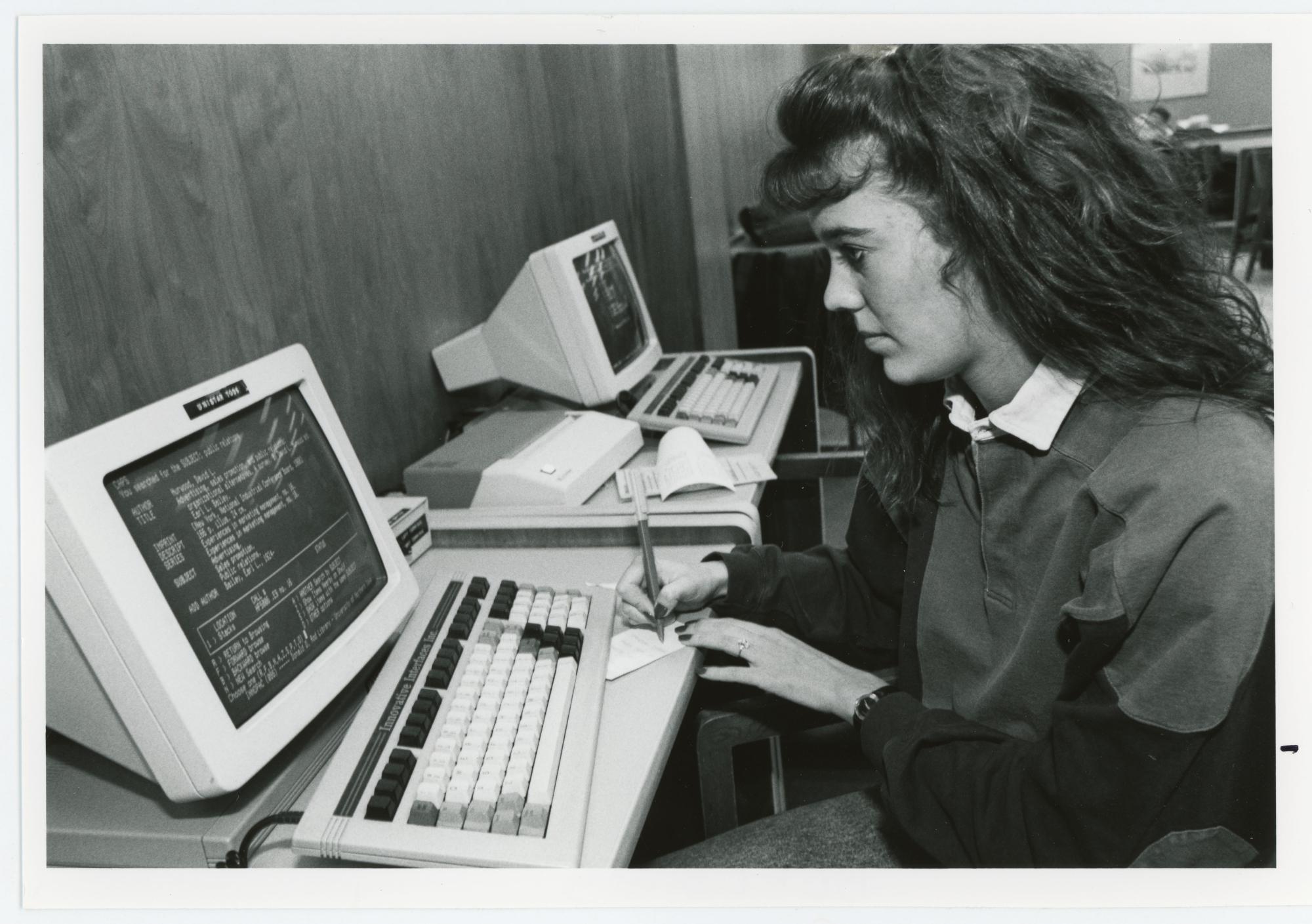

In September 1979 the Library added volume number 500,000, a fine old book by John Harris entitled A Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels, published in 1744. This book was part of an extraordinary collection donated to the Library by Craig and Francis Kennedy of Waterloo. Shortly thereafter, the Reader Service Department added an individual research consultation service. A mild controversy arose in 1980, following the death of Josef Fox, a revered professor of English, philosophy, and humanities at the university for over thirty years. At that time a group of Professor Fox's friends and students circulated a petition asking that the Library be named in honor of Professor Fox. They cited the wide-ranging and deep influence that Professor Fox had had on generations of UNI students. Other people, at least privately, were less enthusiastic about the possibility that the Library might be named for Professor Fox. Some of Professor Fox's ideas, or the way in which he expressed them, had aroused considerable opposition and controversy over the years. In any case, the university administration took no action on this matter. In August 1983 the Library installed an electronic security system at the front door to the building. Prior to that time a library employee had checked students and their backpacks as they left the building. Also in that year the Library offered a specialized computer-aided information retrieval system called "After Dark'. This system allowed students and faculty to perform their own computer searches of subject literature. In September 1986 a student computer lab opened on the lower level of the library. The Class of 1984 donated a device that assisted the visually impaired in their use of library material.

By 1985, Phase III, the next addition to the Library, was on the Regents list of capital improvements for UNI. By January 1987 the project had a $5.8 million price tag, though other capital projects, such as the Business Building, had higher priority. The project would consist of adding a 63,000 square foot fourth level onto the top of the Rod Library. Since this sort of addition had always been in the long range plans, the architects and Mr. Rod had been sure to see that the earlier phases of the building were engineered to bear this weight.

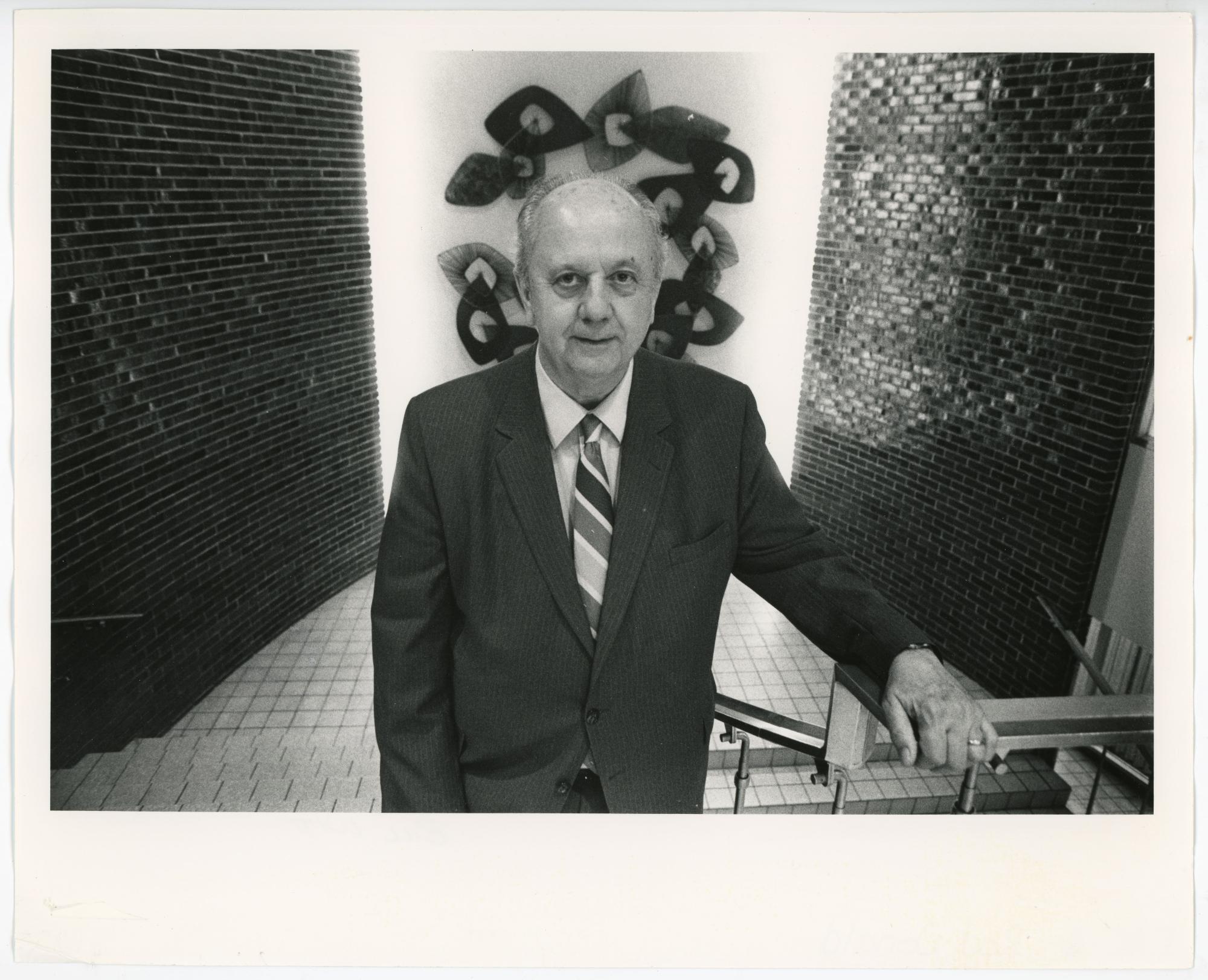

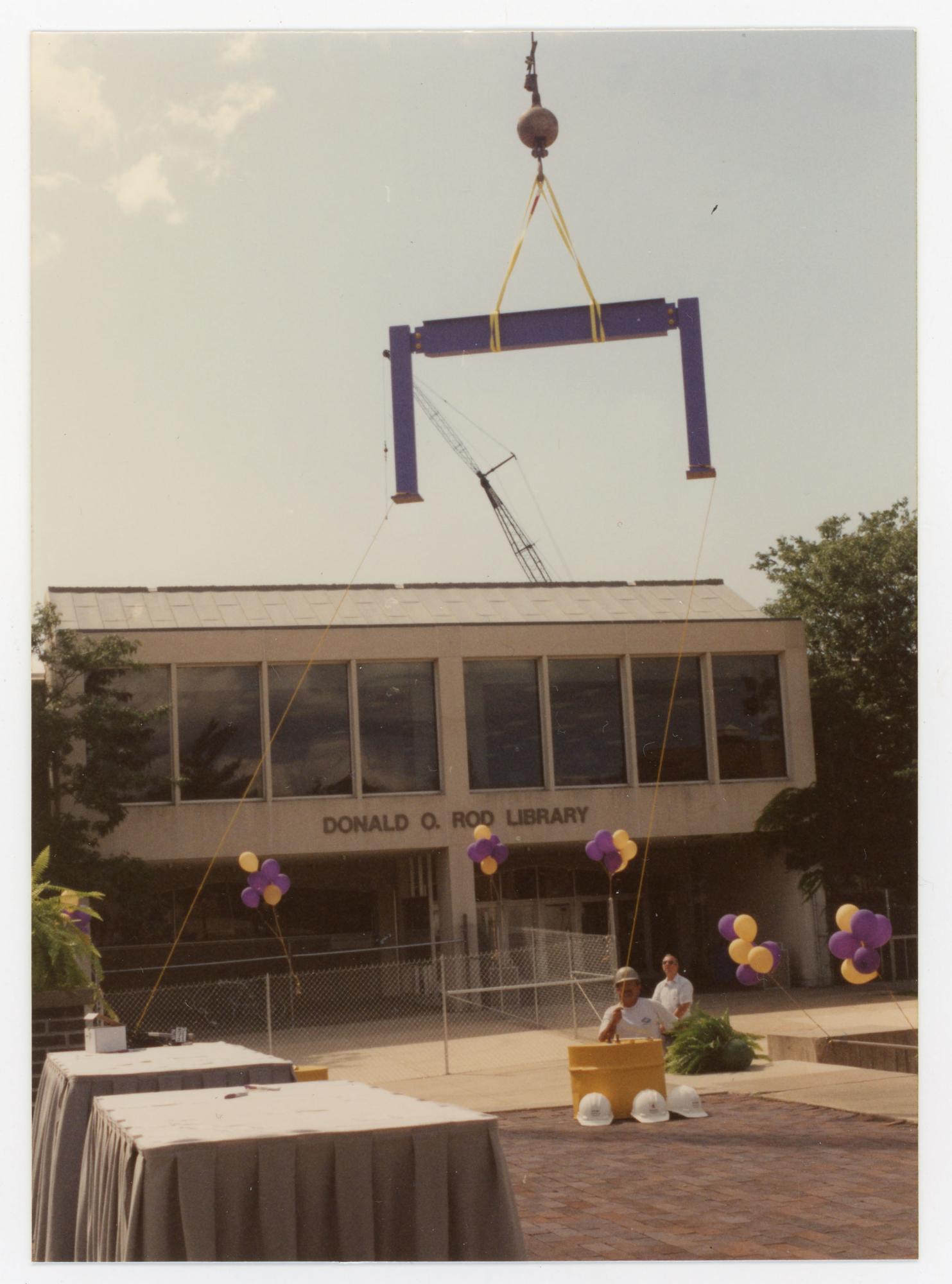

In anticipation of Mr. Rod's retirement on June 30, 1986, the Board of Regents, in April 1986, named the building the Donald O. Rod Library to honor Donald Olaf Rod who served as head of the UNI Library from 1953 through 1986. The name was later shortened to Rod Library to bring it into compliance with campus building naming conventions.

Mr. Rod was instrumental in the development and design of the library and its program of services during those years. In 1953, when he arrived on campus, the library had an operating budget of $70,000, including a book budget of $15,000. The book collection numbered 150,000 volumes. When he retired in 1986, the budget was $2.5 million, with $759,000 earmarked for books. The collection included over 600,000 volumes.

Library Automation and Phase 3 of the Rod Library, 1986-2004

Barbara M. Jones succeeded Donald Rod as Director of Library Services on October 13, 1986. Shortly after she began, Barbara Jones cited four priorities for her work:

- Learn about the Library;

- Begin to plan for library automation;

- Analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the collection;

- Project space needs.

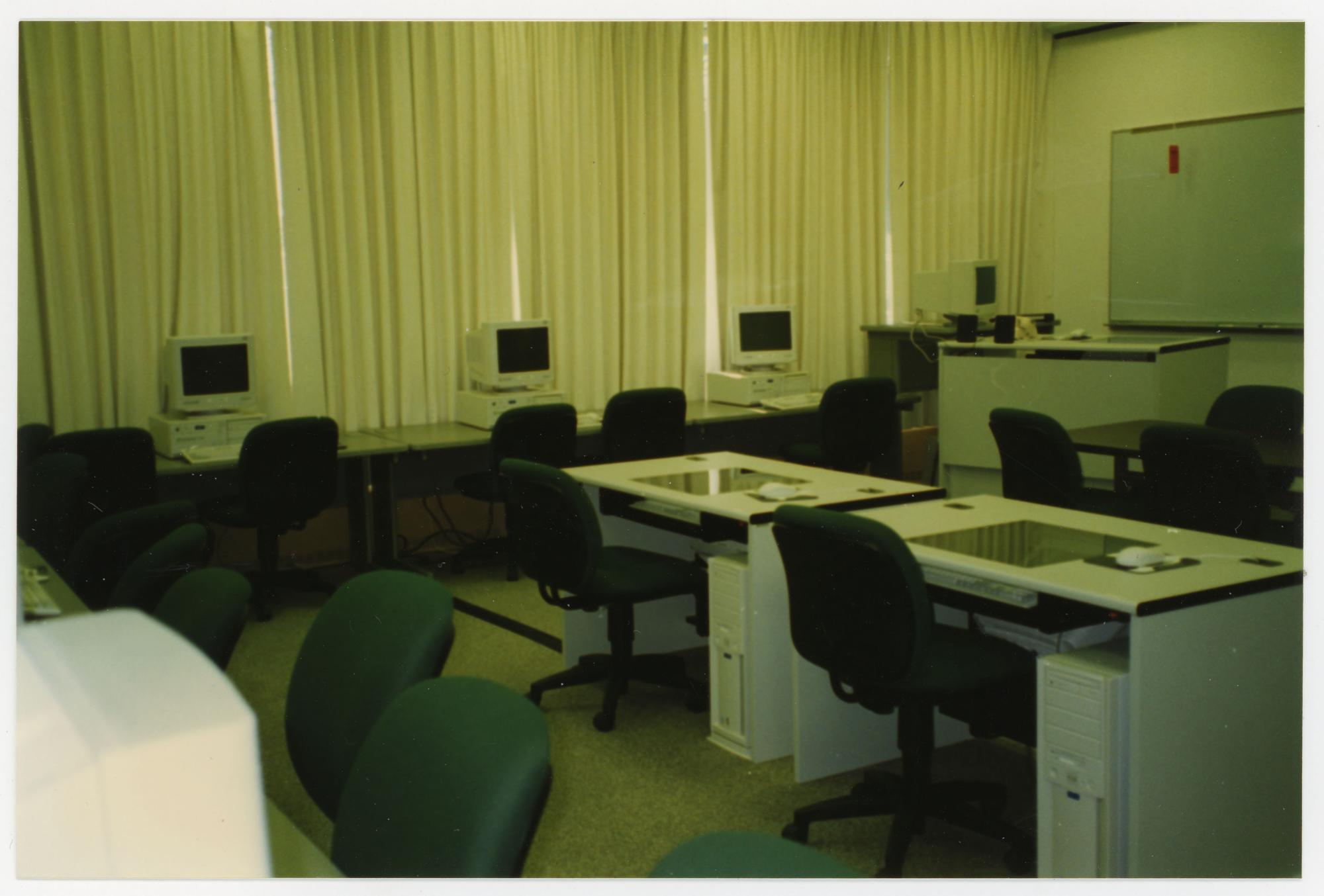

Barbara Jones served as Director for less than two years, but she was remarkably prescient in predicting the matters that have occupied the library staff since 1986. She made an especially good start on library automation and collection management. In the spring of 1987, she arranged a series of demonstrations by library automation system vendors. Some of those initial demonstrations showed systems that were so crude and in such rudimentary stages of development that they would now be laughable. But the demonstrations helped the Library staff to begin to focus on the whole matter of library automation. This was necessary because the Library had made only the tiniest steps toward automation before 1986. Access even to such basic tools as word processing was limited to two IBM PCs in the building by June 1986. At one point Barbara Jones felt the need to send a memo to the staff to calm fears about automation. She assured staff that they would not be losing their jobs, and that, in fact, their jobs would become both less tedious and more interesting. But if some staff members had misgivings about automation, students were enthusiastic about the prospect. Indeed, the Class of 1988 donated its class gift to support the implementation of an on-line catalogue.

Probably the most important contribution that Barbara Jones made toward automation was the appointment of Patricia Larsen as Assistant Director of Technical Services on August 15, 1987, to lead the effort. By September 1987, just a month after she began, Patricia Larsen had an automation timetable in hand. The Library organized a Coordinating Committee, with sub-committees on the public access catalogue, acquisitions, circulation, and serials control, to evaluate and select a vendor for an integrated library system. The committees worked very hard before recommending Innovative Interfaces, a California company that was best known at the time for its work in the automation of library technical services. The Coordinating Committee recommendation in favor of Innovative Interfaces included requests for a number of enhancements in public service aspects of the system, especially keyword search capabilities. The Library administration accepted this recommendation on July 20, 1988. Several harrying months followed as Innovative Interfaces attempted to meet the requests, and librarians attempted to determine if the requests had been met. Ultimately the contract was approved by all parties on November 23, 1988. During this effort to bring a strong automated system to the Library, a number of staff members, notably Patricia Larsen, Barbara Weeg, and Patrick Wilkinson, showed, first, courage in choosing a vendor that was not especially well-known in those days and, second, persistence in requiring that the vendor make changes to suit the needs of the Rod Library.

Barbara Jones also moved ahead quickly in developing what would eventually become known as Collection Management, which aimed to analyze collection strengths and then allocate resources to accomplish the mission of the library. She initiated this effort shortly after her arrival when she scheduled a series of visits by library consultant Jutta Reed-Scott, who helped to organize a Collection Analysis Project. This project looked at a number of important library matters including preservation and collection development. One immediate result was a dispersion of library material selection responsibilities among seven librarians, to be known as bibliographers, who volunteered on a six month trial basis in the fall of 1987. Prior to this, most selection responsibilities had been centered in the Acquisitions Department. Katherine Martin was named Coordinator of Collection Management in September 1988 and then Head of the new Collection Management Department in 1991. Under this new organization, most non-administrative librarians added selection responsibilities to their existing assignments and added the term "Bibliographer" to their position titles. The Library also began to allocate its material resources budget according to a carefully-devised formula for the 1988-1989 fiscal year. Eventually bibliographers set up profiles with a book approval service, initially Blackwell North America and later Yankee Book Peddler, to bring certain books to the Library automatically without their having to be ordered on a title-by-title basis. The bibliographers met as the Bibliographers Council for the first time on October 28, 1988.

There were several other smaller computer-related developments that occurred while Barbara Jones was Director. In September 1987 librarians Stanley Lyle and Gerald Peterson won microcomputers in a university-wide faculty competition. These computers were, first, a welcome addition to the Library's stock of equipment. Money for automated equipment was certainly not built into the budgets of those days. But, second, the award also represented a judgment, from administrative authorities outside the Library, that computers could soon be expected to be a normal part of a librarian's working life. In June 1988 the Library received the CD-ROM version of the ERIC education database on trial; training in the use of this database was held in July.

Barbara Jones did not remain in her position as Director long enough to see many of her significant initiatives come to fruition. She resigned September 23, 1988, and Assistant Director of Public Services Donald W. Gray served as Acting Director. Even though Donald Gray was serving as Director on an acting basis, progress continued in several areas. The Library added a projection panel for CDs in February 1989, and Innovative Interfaces began to install its software in April 1989. By the beginning of the fall 1989 semester, there were twelve terminals installed: eight in public areas and four for the staff. Library Technician Ken Bauer provided invaluable help in making these early installations function properly. In May 1989 the new Head of the Cataloguing, Marilyn Mercado, proposed a barcoding project to be carried out in the summer of 1989. This massive project, which would eventually place a bar code on all Library material, was a necessary prelude to automated circulation. Some years earlier the Library had begun to record its holdings into machine readable bibliographic format in preparation for an integrated system. Records for material that was in machine readable form was loaded during the summer and fall of 1989, with the last tape loaded in October 1989. Retrospective conversion, that is, creating machine readable records for material that did not have such records, continued in a series of projects for many years. In fact, retrospective conversion for certain government documents continues to this day.

Just about all of the Library staff was assisting with the barcoding project when the new Director, Herbert W. Safford, took up his position on July 31, 1989. Dr. Safford was responsible for picking up Barbara Jones' initiatives, establishing his own priorities, and leading the Library in its efforts to provide more highly automated services in an expanded library building. About 350,000 books were coded during this project, which was led by Douglas Hieber and Marilyn Mercado The Library sponsored a contest to name the developing database of library materials: C. J. Hines won the contest with "UNISTAR--UNI System To Access Resources". The new system was dedicated on November 17, 1989. The initial screen display on a UNISTAR terminal was textual rather than graphic.

By today's standards, the screen display looked unsophisticated and the menu lacked many functions that most people now expect from a computer database. However, despite initial problems with response time, caused by insufficient computer memory and faulty equipment, the database functioned well. And it has continued to function well through many upgrades and improvements to its current graphic Web interface. Initially the database was searchable only in the Library, but by the fall of 1990 it could be searched from sites outside the Library. On November 26, 1990, a circulation module was added to the system. The Library began to circulate books through the system on January 10, 1991. The Library ultimately signed off on the public access catalogue and acquisitions portions of the system in March 1991. The initial development of the public access catalogue and the continuing enhancement of the entire integrated system of library services comprise the greatest single automation achievement of the Rod Library. The fact that it worked as well as it did, and as early as it did, made it possible for the Library to focus at least a good portion of its attention on the next major challenge: planning Phase 3 of the Rod Library.

With the overall automation effort off to a good start and on a sound foundation, Herbert Safford stated his own priorities for action:

- Establish procedures for long range and strategic planning;

- Develop uniform library publications;

- Re-organize student hiring practices;

- Plan for Phase 3 of the Library.

Even when the first phase of the Library was still on the architects' drawing board in the early 1960s, there were plans to develop the building in three phases. The first phase had been completed in 1964; the second phase in 1975. By the late 1980s, the need for the third phase was apparent. Bookshelves were full. Work and study space was cramped. Furnishings were shabby and worn out. In spring 1989 the General Assembly approved $15,000 to begin planning for a $7 million library addition that would include space for the Educational Media Center. In November 1989 the Regents selected Herbert, Lewis, Kruse, and Blunck of Des Moines as the architect for the project. Herbert Safford now recalls that the existing structure was, for the most part, easily adaptable to the pending addition and renovation. The building design was a tribute to former Director Donald Rod's foresight. Former Dean Safford specifically cited:

- the building's modular and adaptable structure;

- the construction of an additional elevator shaft during Phase 2 to be used in Phase 3;

- the construction of staircases on the periphery to save interior space for work and service.

But he also remembers that the architects of Phases 1 and 2 were astonished at how they and Mr. Rod had failed to anticipate or allow for the extraordinary growth in library computer technologies. Even this experienced architectural firm, with the expert advice of a nationally-known library architectural consultant such as Mr. Rod, could not foresee this development.

Intense planning efforts, involving most of the Library staff, got underway. Within a surprisingly short period of time, the Library produced a program of services for the new space and recommendations for alteration of the existing space. There were hopes that work could begin as early as 1991. However, due to difficulties in the Iowa economy, construction funding was slow to materialize. Not until June 1993 were the Regents authorized to sell $7.4 million in academic revenue bonds to finance the work.

Work began on Phase III of the Rod Library in July 1993 with a formal roof beam raising ceremony on August 3. Story Construction Company of Ames was the general contractor. The target completion date was summer 1995.

The project would consist of an additional floor on top of the building and extensive remodeling of existing library facilities. Exterior and interior modifications, especially in window design and lounge layout, were also included. Instead of including space for the Educational Media Center, a portion of the fourth level addition would house the Center for the Enhancement of Teaching, as well as bookstacks and study space. Several facilities would be shifted around the existing three levels. The Documents and Maps Collection would move from the third to the second level. The Youth Collection would move from the first to the third level. And Special Collections and University Archives would move from the second to the third level. All periodicals services would be consolidated on the first level. While the most obvious aim of the project was to add study space and book storage capacity, both the architects and Director Safford paid special attention to aesthetics. Director Safford cared deeply about high quality materials, creative architecture, and rigorous physical plant upkeep. While he admitted that students might "never reflect on the elegance of real woods and burnished steel", he hoped "that they will be changed by their surroundings, however subtly, and this will affect decisions they make in creating their own physical worlds after they graduate."

Work went well, despite the complication of juggling both new construction and renovation simultaneously. In fact, Story Construction supervisor Martin Miille cited this complication as an advantage. When his crews faced lulls in one phase of their work, they could refocus their efforts on the other phase. At one point optimists even predicted that the work would be done ahead of time. Much of the renovation work was noisy, dusty, and disruptive. Still, close cooperation between Story Construction and the library staff helped to keep inconvenience to library users at a minimum. During the project, the library was closed just a single day, May 27, 1994, over the Memorial Day weekend, for an electrical switchover. Work was completed on schedule in the early summer of 1995.

Rod Library Phase III Construction, 1993-1995

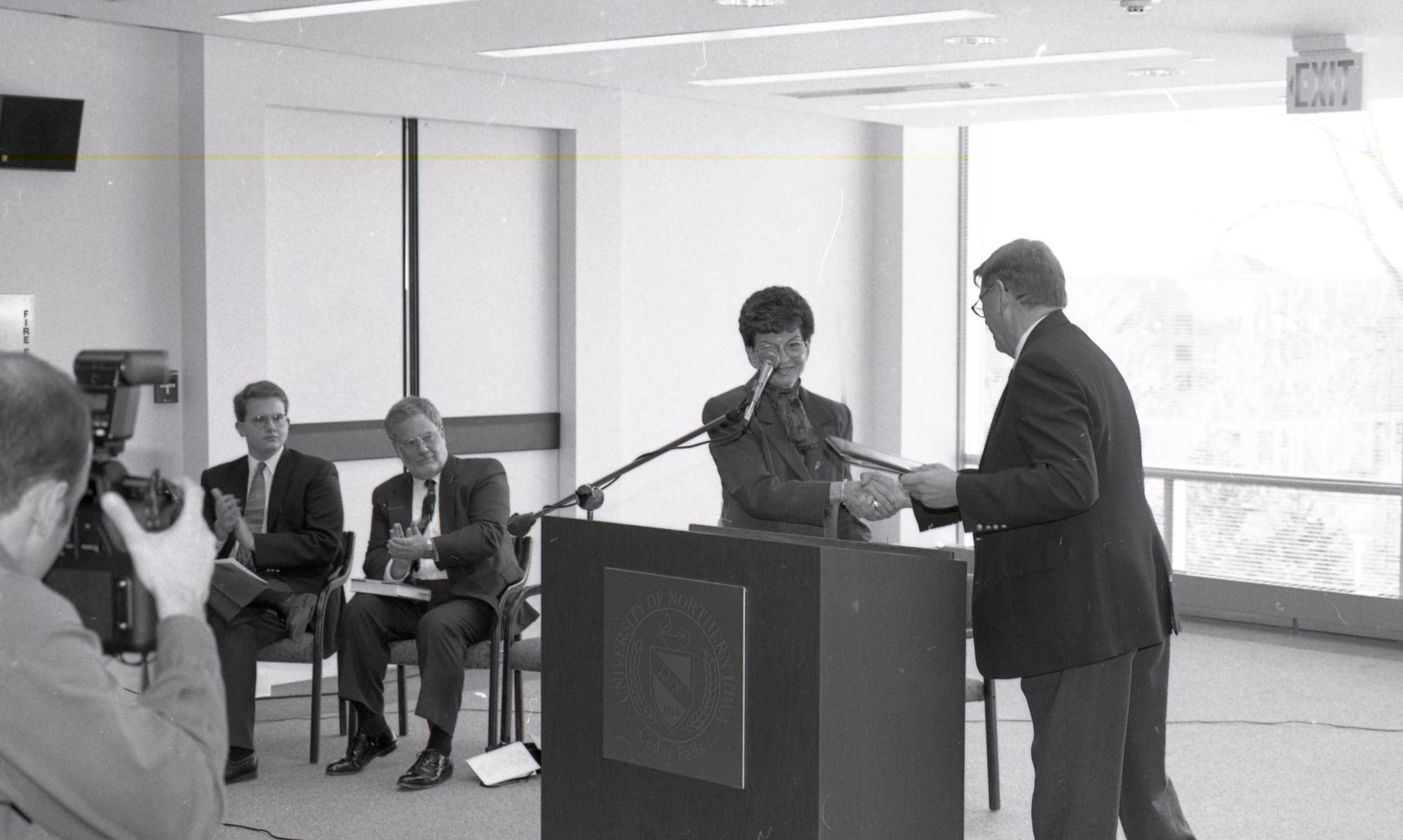

On December 15, 1995, Lieutenant Governor Joy Corning, a UNI alumna, spoke at the dedication of the addition. The project added space for 250,000 additional books, four hundred study spaces, and twelve group study rooms.

Even though the Library staff was occupied for over five years with planning for Phase 3, then waiting for it to begin, and finally watching it happen, there was progress on other fronts as well. In keeping with Director Safford's priorities, the Library consolidated responsibilities for the student employee personnel process by establishing the office of the Student Employment Coordinator in June 1991. This office helped to develop consistent practices, based on reliable information, for the student employees who have always been an important part of the Library staff. Director Safford also put the Library's planning process on more solid ground by bringing in library consultant Maureen Sullivan to lead a strategic planning workshop in July 1992. This helped library staff gain a fuller understanding of the planning process and its perceived benefits. These efforts were important in keeping the Library in step with the University's increasing reliance on strategic planning.

But automation probably remained the focus in the working life of most Library staff members in the 1990s. As Director Safford said, automation was "a significant aspect of who we all are in this profession." He tried to "encourage a library-wide response to technology which endorses initiative, imagination, and flexibility." Automation brought change, including decreased reliance on the print medium. In the first Library Administrators' Council meeting after Director Safford arrived, Patricia Larsen and Marilyn Mercado proposed closing the public card catalogue. As soon as it was possible to transfer cataloguing records directly from the OCLC database to the Library database, they proposed to stop filing new cards and to perform only limited maintenance on existing cards. In January 1990 Patricia Larsen proposed halting the production of the monthly supplement to the printed and bound List of Serials; it was clear from this proposal that the List of Serials itself was on the way out. Public Services librarians, who valued these tested print sources for their work with the public, initially opposed these changes. But as they became more accustomed to the automated catalogue, and as that catalogue improved in performance and appearance, much of their opposition subsided. By September 1992 the public card catalogue was no longer in active use; the cabinets that held the cards were moved out of the building in phases in 1993 and 1994. The last List of Serials was printed in 1993; that final edition was removed from public use in September 1995.

Assistant Director Robert Rose guided several worthwhile efforts in the Public Services area. In 1991 he and Barbara Weeg worked together to define more clearly the library's role and responsibilities for bibliographic instruction. In January 1992 this area was named Library Instruction to reflect a broader role, including instruction in the developing automated resources. Shortly thereafter the Library began to take a serious look at distance education, with special attention to the role that the Library should play in this area. Robert Rose also led a "Re-thinking Reference" initiative in 1993-1994.

Both automation and Phase 3 construction affected the way in which the Library handled periodicals. Probably since its beginnings, the Library had arranged its bound periodicals in alphabetical order by title. For most titles this arrangement worked well. Users of the collection and staff who gave them direction needed only a correct title: they did not need to look up a classification number. But periodicals are notorious for changing titles; slight changes would cause parts of the same journal run to be shelved widely apart. Journal titles that included acronyms or corporate authors also proved difficult for the uninitiated to locate. In March 1989 the library administration approved the classification of periodicals. This project, which took a number of years to implement, assigned classification numbers to journals and brought scattered parts of journal runs together in one sequence. Indices and abstracts, which had also been arranged by title, were classified in August 1992. Coincident with construction, a number of services, including periodical service, photocopy service, and microform service, were consolidated at the former Reserve Desk on the lower level. Since the old Reserve Desk name no longer reflected the array of services available there, Reader Service Head Lawrence Kieffer suggested the new name, MultiService Center. Building on experience during the Phase 3 construction process, the Library also planned to establish a separate Periodicals Information Desk, to be located close to the bound periodicals collection. This desk, as a regular and continuing service point, was ready to be launched in May 1996. But implementation was delayed. Though the Library did offer this service briefly as a pilot project in the spring of 1999, it has not been established as a continuing service.

One of the strong priorities that arose out of Phase 3 planning was a desire to concentrate periodical services on the Library's first level. This was accomplished, but the Library administration knew that the periodicals storage area would need to be modified very soon in some way to accommodate the ever-expanding collection. So, in 1997, Director Herbert Safford and Access Services Head Sarah Mort Cron wrote a grant application to the Carver Trust for compact shelving . The grant was funded at a little over $141,000, with the requirement that the University match that funding level. Sarah Cron resigned in June 1998, so Acquisitions Head Cynthia Coulter and Library Associate Rosemary Meany took on the difficult and complex tasks of coordinating the installation of the equipment and the shifting of collections. A series of technical problems slowed the work, but it was ultimately completed in the fall of 1998. The compact shelving, the location of periodicals published before 1980, gave the collection at least a limited amount of space for growth.

The shift to automated access to the Library's book and serials holdings was revolutionary; by March 1992 UNISTAR was available on the Internet. But the shift in locating information formerly found only in print periodical indices and abstracts was just as dramatic. Since at least as early as September 1988, staff members such as Reference Librarian Stanley Lyle worked tirelessly to make information from the automated versions of these sorts of reference services ever more widely available. Initially the Library offered automated access to certain indices on CD-ROMs. These indices were similar to their print analogues in that they offered only bibliographic citations as results. But in February 1993 the Library began to offer the Lexis/Nexis database, which featured full text articles from many sources. This meant that people no longer needed to take the step of locating articles in print volumes; the articles were immediately available on-line. This also represented the beginning of the shift from locally mounted CDs to remote access to distant databases. The growth of the World Wide Web, the development of full text databases, and the advent of graphical browsers sped up this shift. The Rod Library home page debuted in May 1995. Acquisitions Librarian Tom Kessler developed what was probably the first Library department home page for his department at about the same time. Public Internet access in the Library began with eight terminals in July 1997. By March 1999, the Library had just three CD-based databases remaining on its network.

The automation work of the Rod Library, and specifically its integrated system, has been a model for other libraries and collections. In 1996, the Hawkeye Community College Library and the Cedar Falls Public Library joined the Rod Library to form the Cedar Valley Library Consortium. This consortium has allowed the smaller libraries to benefit from the technology, experience, and expertise of the Rod Library. It has also allowed the Rod Library to obtain more advanced equipment than it could otherwise have afforded. Since the consortium was founded, the Waterloo Public Library and the Allen College of Nursing Library, as well as three UNI campus collections, have become part of the organization.

Under Dean Safford's leadership, the Library began several international exchanges with libraries in other parts of the world. At this time the Library has continuing exchange relationships with libraries in Klagenfurt, Austria, and St. Petersburg, Russia. Under auspices other than the Library, several librarians have also visited China and Slovakia.

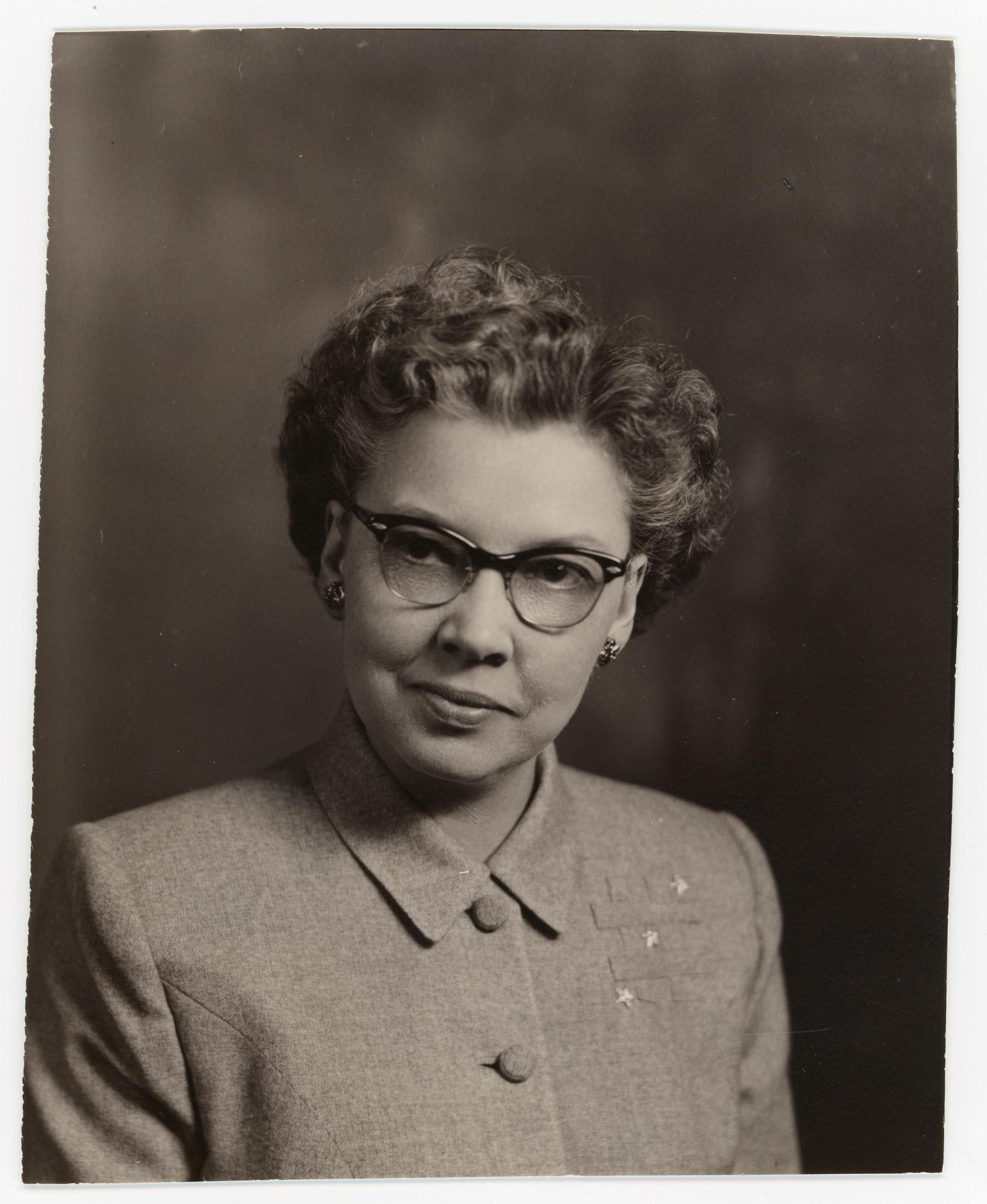

Herbert Safford resigned as Dean of Library Services to take another position in the Library on June 30, 2000. He was succeeded by Associate Dean Marilyn J. Mercado on July 1, 2000, initially on an interim basis. On July 1, 2002, she became Dean of Library Services. Despite the recent economic circumstances that have required some hard decisions, the Library has continued to offer new services including a striking array of Web-based databases, virtual reference service beginning in July 2002, and streaming audio for course reserves for the fall 2003 semester.

Currently, in addition to its regular complement of library facilities and services, the Rod Library houses the Division of School Library Media Studies of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, a student computer laboratory, a copy center, and the Office of Information Management and Analysis housed temporarily in the former Center for the Enhancement of Teaching.

In September and October 2004 the Rod Library scheduled a series of events to commemorate Donald O. Rod, the 40th anniversary of the Rod Library, and the acquisition of the one millionth volume.

Conclusion

The Library has been an integral and successful part of the UNI community for 128 years for many reasons.

- First, there has been strong leadership, including two directors who each served over thirty years, that provided both stability and innovation.

- Second, library resources have not been fragmented by the multiple, duplicative department or subject libraries that plague many campuses. It is impossible to state precisely why significant department libraries did not develop at UNI, but perhaps this is due to the relative compactness of the UNI campus, the exclusive curricular focus on education until 1961, and the continued reliability, strength, and reputation of a centralized library over the years.

- Third, the size of the UNI library is conducive to the sound delivery of excellent service at the appropriate time. The Library is not so small and underfunded that every little change is a struggle, nor so large that every change must overcome massive bureaucratic inertia. It is large enough to have a reasonable level of staffing and funding, but it is small enough actually to undertake innovations when they are appropriate. The size of the Library also has made it easier to respond to and accommodate curricular changes and patron requests.

- And, finally, a dedicated library staff has helped to make good things happen in good order, such as planning for new facilities, developing new programs of service, delivering library instruction, managing and describing the collection, and helping patrons get through the bewildering array of computer-aided research methods.

It is difficult to see where library service may be headed in the next ten years, let alone in the next 128 years. Anyone who has worked in or around libraries before and after the advent of the World Wide Web in the middle 1990s has seen library service radically transformed. Some innovative thinkers now believe that the print medium is dead. They think libraries may as well discard their book collections. On the other hand, some traditionalists believe that digital media are unproven, unreliable, and transitory. They believe that researchers cannot trust the information that they find on the Web today, and, even if they could trust it, it will not be there tomorrow. No matter where the future may lead, however, it seems very likely that library services at UNI will continue to respond to the needs of the UNI community to conduct effective research, learn about the world's cultural heritage, and become thoughtful, productive, educated citizens.