Introduction

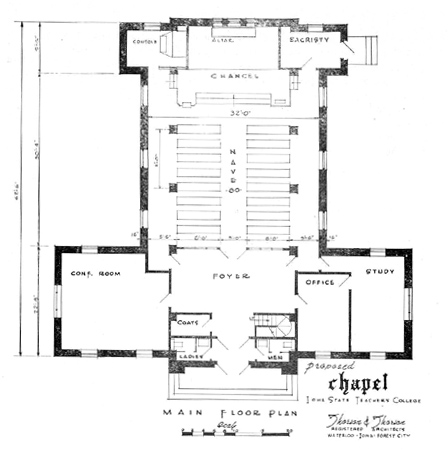

You might think that the image at the head of this essay looks vaguely familiar, but it is not a building that you have ever seen. Rather, it is a drawing of a chapel that was proposed for the UNI campus in the late 1940s, but was never built. The Chapel is a good example of institutional planning that never quite took tangible form.

Just about any long-lasting institution considers its future carefully and makes plans accordingly. For a variety of reasons, some plans are realized fairly quickly, others take years to accomplish, and still others never come to fruition. This brief essay looks at four buildings that were planned for the UNI campus, but were not built in a form that resembled their original, proposed appearance.

- The Phantom Library--an octagonal library near College Street

- The Phantom Dormitory--a men's dormitory near Baker Hall

- The Phantom Chapel--a small devotional center near the East Gymnasium

- The Phantom Tower--a third high rise for the Towers Complex

The Phantom Library

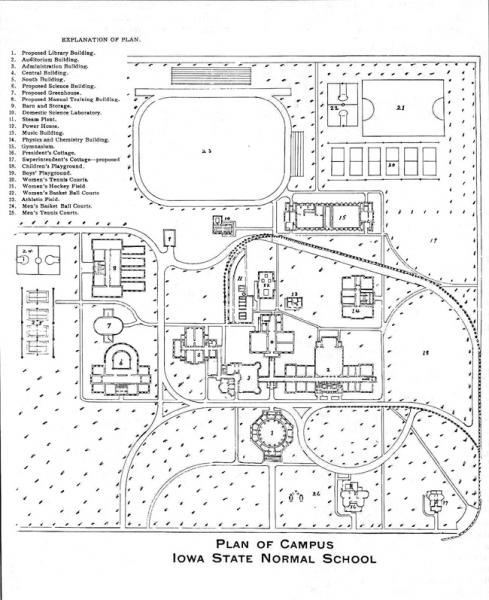

If the earliest phantom facility had been built, it would have been the school's first building constructed specifically to serve as a library. In the school's first thirty years of existence, from 1876 through the early years of the twentieth century, the library collections were housed in a series of makeshift campus locations. Each of those locations featured cramped quarters that were ill-suited for study, scholarship, service, or an expanding book collection. President Seerley was a fervent believer in a strong, well-housed library, managed by a professional staff. In 1905, as part of a very early campus planning effort, he drew up the following plan.

President Seerley foresaw a much more compact campus than the one with which we are familiar today. The campus of his day, after all, consisted of only about forty acres; today's campus is over six hundred acres. However, his vision does show a striking resemblance to today's general campus plan, with academic buildings on the east and playing fields on the west. One prominent feature (noted, probably not accidentally, as Building 1 on the plan) is a new library, to be located in the middle of the eastern edge of campus, close to the instructional buildings of that day and just off College Street. It would have been situated near the present location of the President's House. A special feature of this proposed building is its octagonal exterior walls. The circular shape within that octagon might well have represented a dome over a central reading room.

But the octagonal library was never built. Instead, in 1908, work began on a relatively traditional style library building on the southeast corner of campus, in the space assigned to a proposed science building in the 1905 plan. The new library building, known today as Seerley Hall, served as the campus library from 1911 until the opening of what is now known as Rod Library in 1964. The octagonal, and possibly domed, library would have made a remarkable, if not especially functional, addition to the campus front yard.

The Phantom Dormitory

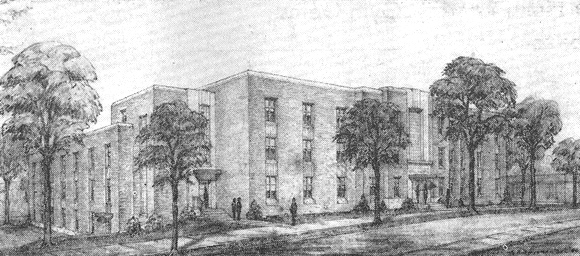

A second phantom facility was a men's dormitory that was planned to be built south of Baker Hall. Plans for this facility surfaced shortly after World War II, when both married and unmarried men returned to college in large numbers with the help of the GI Bill of Rights. The college developed Sunset Village, in the area now occupied by the parking lot west of the Industrial Technology Center, for married veterans and their families. The military surplus metal Quonset huts and barracks buildings of Sunset Village were meant to serve for five years, but they ended up lasting twenty-five years. In April 1946, the alumni magazine, The Alumnus, announced that the college would build a new dormitory to house two hundred single men. It would cost about $300,000, and be located south of what is now Baker Hall. The new dorm would be U-shaped, but it would resemble Baker Hall. Rooms would feature wardrobe closets and built-in study tables. Most rooms would be doubles, but there would be a few singles as well. The lower two levels would include service and recreation facilities. Nemmers, Clark, and Spooner of Des Moines were named as architects. Construction would start "as soon as material and labor are available".

Plans still seemed to be on track in January 1947 when the student newspaper, The College Eye, featured a sketch of the proposed building and outlined specifications similar to those presented a year earlier in The Alumnus. Work would begin "when materials are available". But construction on this facility never got underway. Shortages of construction material and postwar inflation made campus projects difficult to finance and build even as late as 1950, when construction on Campbell Hall began. While a freestanding men's dormitory south of Baker Hall never was constructed, the idea of providing additional living space for men in that area did not die. In 1958, the college opened a dormitory addition between Baker Hall and what was then known as Seerley Hall for Men. This addition joined the two freestanding men's dormitories into one large building and included a wing that extended south from the area that joined the two buildings.

Initially this united building was known as Seerley-Baker Hall. But in June 1961, the Board of Regents changed the name back to George T. Baker Hall (or Baker Hall) to eliminate the hyphenated name. In January 1964, when library services were moved to the new Rod Library, the name "Seerley Hall" was applied to the old library building .

The Phantom Chapel

In May 1947, President Malcolm Price spoke about building a college chapel to an audience gathered for an alumni reunion. The Class of 1922, on campus for their 25th anniversary, took this project as a challenge. Under the leadership of Russell Lamson, the class decided to begin a fund drive. Vernon Bodein, Director of Religious Activities, described the need for such a facility in the October 1947 issue of The Alumnus. He stated that the college already had a strong religious background, with a variety of religious centers surrounding campus, the College Hill Interdenominational Church that held services weekly in the Auditorium, and the multitude of activities associated with the annual Religious Emphasis Week. But he believed that "young people do need to have a place where they may meditate in a peaceful, soul-quieting atmosphere". He said, "We believe that the emphasis we give to religious life should be symbolized by a chapel of great beauty and appeal" and that belief should be "given expression in a chapel, centrally located on the campus, for the use of everyone in the college community".

In the fall of 1947, the Student League Board formed a student chapel committee and Dean of the Faculty Martin Nelson formed a faculty chapel committee. The alumni, faculty, and student committees worked toward a goal of raising about $50,000 to build a chapel in an area south of the Commons and west of the East Gymnasium. The groups raised awareness about the project by erecting a sign on the Chapel's potential site for Homecoming 1947. They hoped to be able to dedicate the new building at Homecoming 1948. Early on, the Danforth Foundation offered a substantial gift toward the building fund. While there was initial enthusiasm for the gift, there were also certain conditions attached to it. Ultimately, the gift was rejected.

The appearance and potential functions of the new chapel emerged in early 1948. Thorson and Thorson of Waterloo were selected as architects. The building would accommodate about seventy people on its first level, with room for an additional twenty in the balcony. The Director of Religious Activities would have an office and a meeting room in the Chapel. The building would be Christian, but non-denominational. It would serve as a site for marriages, memorial services, and meditation. But the building would not be used for regular Sunday services.

The Alumnus featured enthusiastic reports about the Chapel fundraising campaign in just about every issue during the late 1940s. Each issue carried a list of new contributors to the fund. Some contributors sent touching notes with their contributions. Eva May Sinn wrote: "It is approaching 50 years since I entered the old S. N. S. (State Normal School, UNI's first name) as a young girl from country school. I have never forgotten the friendly Christian atmosphere I found. I am glad to contribute a small bit to the chapel. I wish it could be more, but alas! Retired school teachers are not affluent."

By January 1949 the fund had 225 contributors. By July 1949 about 900 contributors had given a total of $6768. While this was a nice sum of money for that day, it represented only about 10% of what the Chapel Committee thought that it needed as postwar inflation pushed construction prices upward. Perhaps beginning to sound a bit shrill, the writer of the July 1949 article in The Alumnus calculated that each living alumnus or alumna needed to give just $3.70 to bring the fund to its goal. However, the appeal failed to generate sufficient interest. By September 1950 the fund had reached $8404, but thereafter there is little reference to Chapel fundraising activities in college publications.

By the early 1960s the college was trying to find appropriate ways to meet the social and recreational needs of its expanding enrollment. Initially the college planned to make substantial improvements and renovations to the Commons, the building that had served as the student union since 1933. Included among the improvements was a plan to remodel a portion of the Commons into a chapel area. Money from the Chapel Fund would be used for this work. Some students objected to this plan: they thought that the proposed chapel space could better be used for meeting rooms, recreation areas, or a bookstore. However, this issue never came to a head. The college changed its plans and decided to build a completely new building, now known as Maucker Union. Apparently a portion of the Chapel Fund was devoted to the Maucker Union Meditation Room, located in the northwest corner of the Union.

The Northern Iowan reported in 1983 that the Chapel Fund was called on once again to help fund repairs on the Campanile. The last fiscal vestiges of the proposed Chapel disappeared in 2000-2001, when the Chapel Fund account was declared dormant and, consequently, closed.

The Phantom Tower

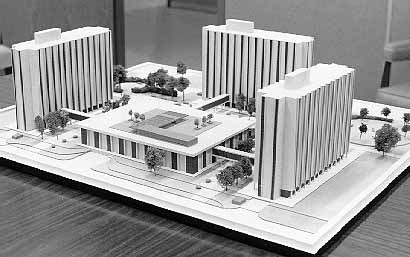

In the middle 1960s, with Baby Boomers swelling enrollment, President Maucker proposed a 600-bed high rise dorm to be located just north of Campbell Hall. The new dormitory would be connected to Campbell Hall by means of shared dining facilities. The Board of Regents approved preliminary plans for this project, described by one Regent as "a shock to the skyline", in May 1966. The architect squeezed the project into a tight $2.88 million budget by removing one floor and eliminating in-room lavatories from the plans.

But by October 1966, plans had changed radically. Instead of one tower connected to Campbell Hall, there would be two towers built farther north in a complex of their own. They would be connected to each other by means of a dining and recreation center; this would be the Towers Complex and the Towers Center that we know today. What's more, the dining and recreation center would have the capacity to serve a third tower. Work began on the Towers in February 1967. Construction was slowed by strikes, but Bender Hall opened in January 1969 and Dancer Hall was completed in June 1969.

But what about the third tower? In April 1969 the Board of Regents authorized UNI to negotiate with architects on the design of the third building. However, UNI officials began to have reservations, even to the point of suggesting a twelve-month moratorium on construction of dormitories.

At the July 1969 Regents meeting, President Maucker said, "Second thoughts, based on uncertain regular enrollment, changed student attitudes toward residence hall living, increased off-campus facilities and changed university regulations permitting greater use of these facilities, construction costs, and at the last Board meeting an inquiry regarding the possibility of our arranging reduced rates for overcrowded and perhaps under-serviced facilities for students of limited means, all lead us to suggest this moratorium." In short, enrollment projections, changing student attitudes, and higher costs led UNI to question whether or not additional dormitories could generate enough income to pay off the bonds that would finance new construction.

Later in the summer of 1969, in the "Ombudsman" column of the Northern Iowan, a questioner alluded to the rumor that the third tower was planned to have been used to accommodate married students. The editor of the column responded that, with the moratorium, UNI might look more closely at apartment-style units instead of "egg-crate" style buildings. UNI did build the Hillside Courts apartment-style units shortly thereafter, but twenty years passed before the construction of another dormitory for single UNI students. And that new dormitory, the R. O. T. H. complex, was certainly very different from the style of the high rise Towers Complex.

Summary

What is the prospect for any of these phantoms ever coming to life? In short, not very good.

- An octagonal library presents major problems in the efficient arrangement of bookstacks. And, at this point, the research needs of UNI faculty and students are served well by the Rod Library.

- A new dorm in the vicinity of Baker Hall seems quite unlikely. First, Baker Hall was converted from dormitory to office space over thirty years ago. And second, the general trend of current campus planning tends to put student housing on the edges of campus and saves space on the central campus for instructional facilities.

- How about a Chapel? If ever there was a time when such a project could have been successful, it should have been in the wake of World War II. But the Chapel project did not come close to raising enough money then, and it seems most unlikely that it could raise enough money now. In addition, lines between religion and the state have hardened since that time; this would serve only to complicate the matter of building a chapel on a state university campus today.

- A third tower might have the best chance of emerging from its phantom status, though even here the chances seem slim. After something of a nadir in 1980s, dormitory life seems to have improved in recent years. Buildings have been renovated, students have taken the initiative to make their rooms more homey (if also more crowded), and hall staff have worked hard to make life more pleasant and interesting. But in recent years attractive options for student housing have also appeared off-campus, both in the College Hill neighborhood and west of Hudson Road. UNI would need to experience an extraordinary enrollment surge before it could commit itself to bonding for another 600-bed dormitory.

So, the phantom facilities are likely to remain just that--surges of enthusiasm during a particular era, dreams that never quite took tangible form, shadows on the landscape that we walk every day.

Compiled and written by Gerald L. Peterson, Special Collections Librarian and University Archivist; scanning by Gail Briddle, Special Collections Assistant, October 2002.