Sunset Village (1946)

The end of World War II brought an unprecedented challenge to the Iowa State Teachers College. Large numbers of veterans, many married and with families, were starting or continuing college with the help of the GI Bill®. These families created a need for housing that neither the college nor the Cedar Falls community could meet in a timely manner. The college anticipated this need, but the Iowa Attorney General ruled that the State Board of Education (now the Board of Regents) did not have the authority to provide housing for married students and their families. The Board of Education persisted and ultimately convinced the Attorney General that the Board did indeed have the authority, but valuable time was lost while the parties established their legal positions.

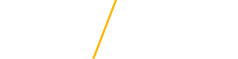

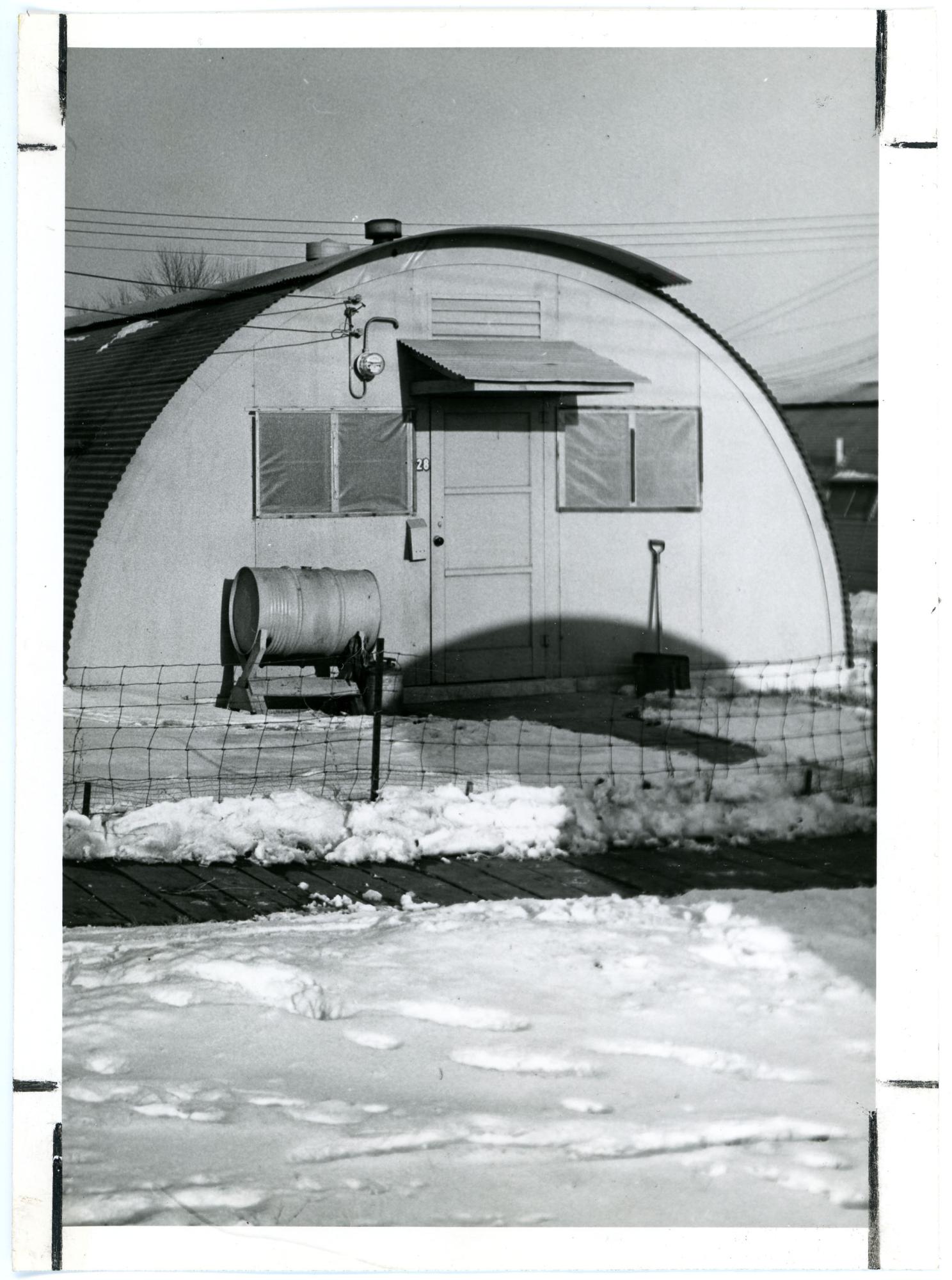

Consequently, President Malcolm Price had to wait until spring 1946 before he could make arrangements with the Federal Public Housing Authority for surplus Quonset huts and metal-sided barracks buildings to be shipped to campus. The housing units were free, but the college invested $40,000 in infrastructure such as water and sewer lines, roads, electrical power, and concrete slab foundations. The initial shipment of eighteen Quonset huts came from Oregon, and, by 1947, a total of seventy-two buildings had arrived on campus.

While the arch-roofed Quonset huts seem to be the buildings that most people remember, the photo at the head of this article shows that the conventional metal-sided rectangular barracks buildings were much more numerous.

The buildings were approximately 48 X 20 feet. Each building was divided into two "apartments", with a living room, kitchenette, and two bedrooms in each unit. Kucharo Construction Company of Des Moines was in charge of erecting the buildings. All units were intended for married veterans. While these veterans were mostly students, a few married veteran faculty members lived there until they could locate more permanent housing. The buildings were meant to be temporary, with an anticipated life of about five years. The site for these buildings was a forty-seven acre tract, acquired by the college in 1941, near the site of the current Industrial Technology Center parking lot.

In May 1946, Dean of Men Gordon Ellis solicited applications to live in the units. Priority was given to veterans with families and to veterans who had no housing or were living in substandard quarters. Solicitation for applications continued during the summer of 1946. Authorities hoped that some units would be completed by the end of that summer. The student newspaper, the College Eye, ran a contest to name the new housing area. James Loomer won a $5 prize for his suggestion, Sunset Village. Unsuccessful suggestions included: Teecyville, Sunshine Slope, Iowana, Veteran Valley, Atomic Reserve, and T. C. Reserve.

Construction initially progressed fairly well, but then stalled. By the fall of 1946, most of the work was done. But, due to the postwar shortage of construction material, plumbing equipment proved to be almost impossible to obtain. Finally, in October 1946, some plumbing fittings and fixtures did arrive and were installed. Construction workers were able to complete interior finish work and, on November 6, 1946, the first seven families moved in. Most of these families had been living in Riverview Bible Camp cottages, which were fine for summer occupancy, but not meant for cold weather. The heads of these first seven families were:

- Peter Hiltis

- Ray Collins

- Fenton Isaacson

- James Nelson

- Glenn Starner

- Fred Steinkamp

- George LeVasque

The veterans organized themselves into a group called Quon-Vets (Quonset Veterans), whose purpose was "expediting procurement of materials needed for completing the structures of the village." With only four of the seventy-two buildings available for occupancy, this was a laudable aim. Fenton Isaacson was the first president of the group. Quon-Vets members visited building supply manufacturers in Minnesota and western Iowa to impress upon them the need for their products. Whether as an effect of the Quon-Vets visits or coincidence, a carload of wallboard and a shipment of heating stoves arrived on campus in December 1946. By mid-December, eighteen huts were available for occupancy. The College Eye lauded the Quon-Vets as "truly displaying the American spirit." In a touching article on families moving into the huts and creating homes, the College Eye noted that "Some of the wives are breaking out their linen and china that have been stored with the 'folks' during the war years. For many it is the first opportunity to use wedding and shower gifts."

The winter of 1946-1947 was a productive, but difficult time for Sunset Village families. The surplus metal buildings were neither insulated nor weather-tight. Mice were abundant. Homes were difficult to keep warm with oil heaters that required constant maintenance. Roads were mud. Sidewalks did not exist. Due to the poor condition of village roads, deliveries of mail, ice, and oil were unreliable. Milk deliveries, essential to the young families, usually came early in the morning when the roads were still frozen and passable.

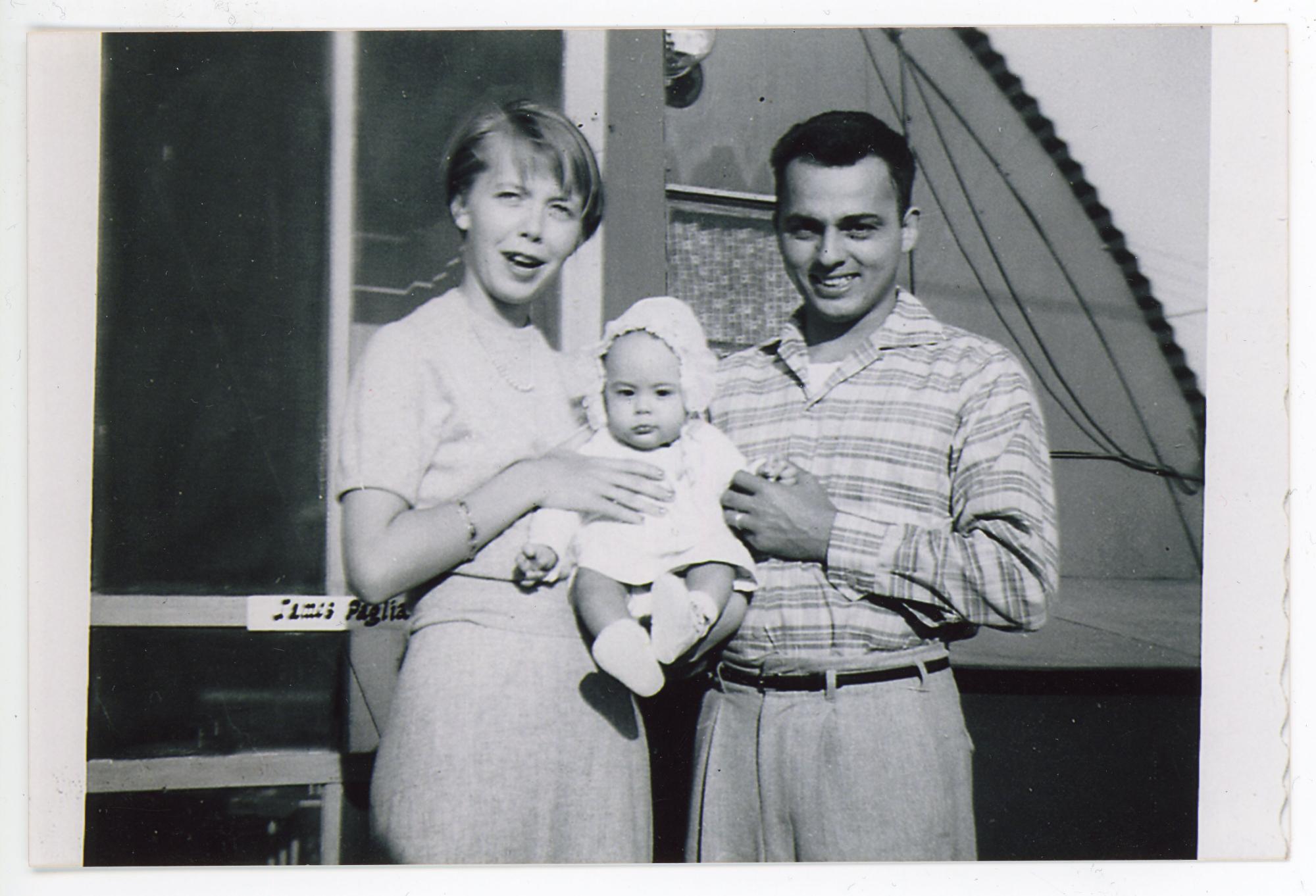

But the college and the families combined forces to make Sunset Village a community worth living in. The college spread cinders on the roads, and college students from the dormitories provided babysitting services to the families. Three families welcomed new babies. The wives started a Women's Club that brought in speakers on childcare, nutrition, and homemaking. Many families found that juggling responsibilities for school, work, childcare, and homemaking required complicated schedules.

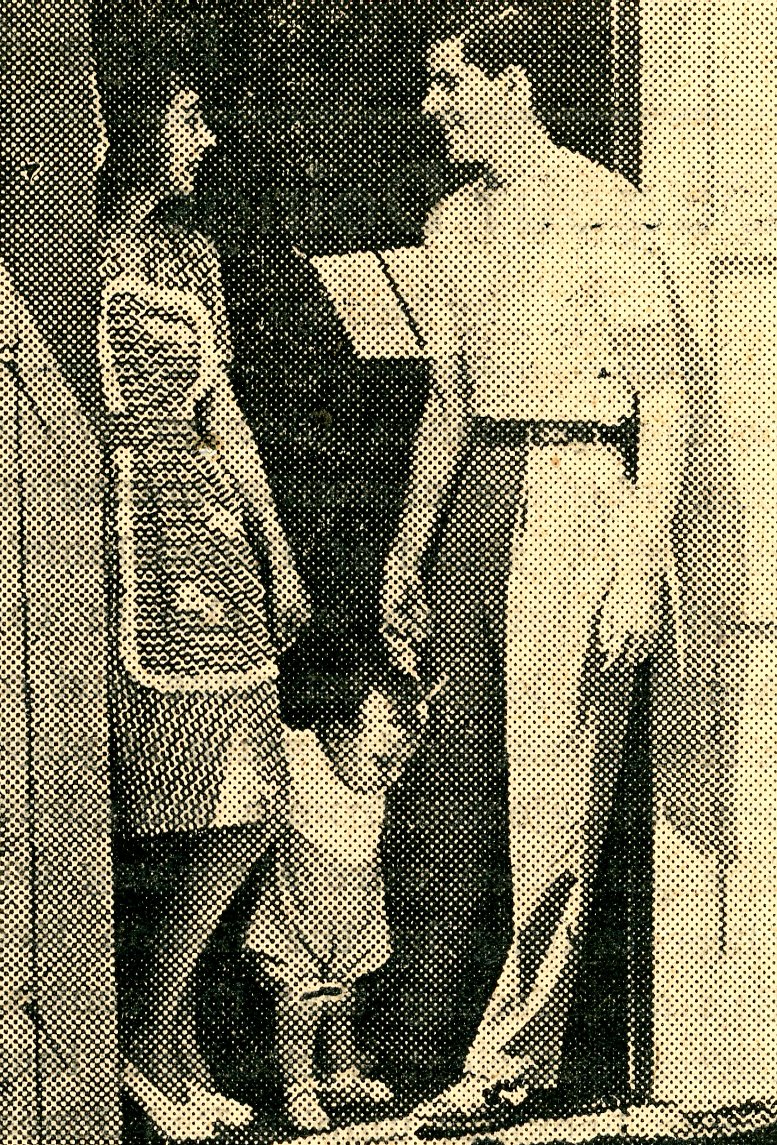

The community also worked hard to found and develop a cooperative grocery store in the village. Families contributed $20 each to build and stock the small store. The store opened in May 1947 and was available initially for about twenty hours per week. The store's prices aimed at meeting costs plus making enough to cover management expenses. Lawrence Shepard was the store's first manager.

In another attempt to provide themselves with basic necessities, seventy families obtained garden allotments on college land near the village in the spring of 1947.

Improved roads meant that mail could be delivered to each hut, but families found that the cinder surface led to many skinned knees for the children, who had no other place to play. By the summer of 1947, about four hundred people lived in Sunset Village. Rent ranged from $20 to $33, depending on family income level. Probably the biggest problem faced by families as the fall and winter of 1947 approached was securing a dependable supply of heating oil. Since each unit was heated by an individual oil heater, and since many families had small children, fuel oil was a critical need. The village as a whole would need at least 20,000 gallons of fuel oil for the winter. The college offered to supply each family with winter heating oil for $168 per unit. Village residents rejected the offer, but, when December arrived, they had come up with no better solution. So the college brokered a deal. Four local fuel oil suppliers divided the village into supply areas for which they would be responsible. The companies promised to make regular deliveries, and, should it prove necessary, the college promised to assist in collection of bills. In addition, the college installed its own emergency fuel oil tanks in case village residents ran into supply problems. But local arrangements could do little to counter a nationwide shortage of heating oil. Local fuel oil companies depended on distributors. Distributors depended on refineries. If refineries did not produce enough fuel oil, there was little that local companies could do. By the end of January 1948, the situation was critical. Some oil heaters were converted to burn coal or wood. Some families moved in together to conserve fuel. Some men sent their wives and children home and moved into the dorms. Only warmer spring weather brought relief from this difficult situation.

Spring brought an agenda for outdoor improvements. One need that would surface again and again over the years was a suitable playground for village children.

The college designated an area about 100 X 150 feet for a playground, and installed a hard surface on part of that area for skating and bike riding. Several Waterloo and Cedar Falls organizations donated cash and equipment to improve the playground. In August 1948, the college administration asked the federal government to transfer the Sunset Village buildings to college ownership. The college would continue to give housing priority to veterans, as the federal government had initially stipulated. In December 1948, the college installed electric meters in each hut. Prior to that time the college had paid for electrical service to the entire village. Following the meter installation, the college would pay an initial $2.50 on the bill, but residents would be responsible for the remainder.

The occupancy rate remained high in the village, even when the college expected veteran enrollment to decline. In early 1950, with the housing situation difficult for even single men, the college explored plans to convert about a dozen village huts into barracks style housing for groups of ten or twelve single men. But by the summer of 1950, all units were again occupied by families, and the college abandoned plans to convert village units to other kinds of housing. In 1951, with the huts nearing the end of their five-year anticipated life, the College Eye asked what the future would be for Sunset Village. The units were still in great demand: four hundred people, one hundred of them children, still lived in the village. The low rent and expenses made the village very attractive to young families: rent was $23 per month ($5 more for furnished units), water was free, heat was about $20 per winter month, and electricity was minimal. But the huts were still uninsulated and the roads were bad. Either the huts needed to be upgraded or some other permanent solution needed to be found.

Tom Pettit, then a College Eye reporter and later a national broadcaster for NBC-TV, summarized the situation nicely in 1953. He noted that veteran enrollment was down, but that married students had become a fixed part of college life. What is more, the college's new program of graduate study meant that numbers of married students would likely increase; for example, over half of the men enrolled in the summer of 1953 were married. Mr. Pettit investigated the finances of Sunset Village and found that the capital costs had long since been amortized; rent from the village was essentially underwriting bonded indebtedness of the college dormitory system. In an interview, President Maucker said that the intention was to "maintain it (Sunset Village) as long as we can. Beyond that there is no provision. I don't see any possibility of it." President Maucker said that the level of bonded indebtedness in the dormitory system precluded any substantial improvement in housing for married students in the near future. Mr. Pettit offered several solutions to the problem. His first solution involved converting Campbell Hall into a men's dormitory and remodeling parts of Baker Hall and Seerley Hall for Men into family apartments. His alternate solution was to make Sunset Village a permanent facility and to undertake substantial upgrades and improvements.

Despite Tom Pettit's interesting analysis, Sunset Village life continued on a normal and predictable course for several years. In the spring of 1954 village resident Diane Sargent wrote a series of columns entitled "Sun Spots" in the College Eye. She wrote with good humor about the problems that village residents continued to encounter: loose pets, mud, deteriorated playgrounds, trash, dirty oil heaters, parking, thin walls, and bad roads. Not until December 1955 did a glimmer of change begin to appear when the Regents approved $180,000 for the construction of twelve two-unit buildings that became known as College Courts. This first batch was completed in December 1956, and a second similar batch of twelve two-unit buildings was ready in January 1959.

The permanent structures of College Courts were clearly a step in the right direction for married student housing at the college, but they actually had little effect on Sunset Village. Several Sunset Village units were converted to storage facilities, but, even after the college installed fifty house trailers in South Courts just southeast of Sunset Village in the summer of 1963, village occupancy rates remained high.

By the middle of the 1960s, arguments about the future of the village took on a more serious tone. More traffic in the village meant more danger to children. In an ironic twist, a child was struck by a car while the village was in the midst of a campaign to enforce a ten mile per hour speed limit. After a December 1965 campus inspection, the State Fire Marshall suggested vacating the village. He cited the considerable danger posed by the units' single entry door and the small, high, windows that could make egress difficult in an emergency. Later in the 1960s, the Fire Marshall found that several of the units that were being used as studios by the Art Department "Do not meet any of the standards related to fire safety in school buildings." President Maucker understood the gravity of the recommendations; however, he also had to consider the pressing need for married student housing. He stated that there was simply too strong a demand for family housing at that point to vacate the village immediately. Even in the late 1960s, applications to live in Sunset Village exceeded available units by a 3:1 ratio.

In April 1969, the college purchased the land on which Hillside Courts would eventually be built. At that time, to underline the necessity for new housing units, college planning administrator Marshall Beard said, "The Quonset hut buildings have been unsafe since they were built." But, even as Hillside Courts construction progressed, students expressed their affection for the Sunset Village level of housing: one survey found an 88% satisfaction rate among residents with factors such as rent, amount of space, and location. Some students did not look forward to paying rent in the $100 range in the new Hillside Courts apartments.

In the summer of 1970, the university announced that the Sunset Village units would be phased out as they became vacant: that is, when a tenant moved out, the unit would be decommissioned.

For the fall of 1971, with Hillside Courts apartments nearing completion, the university offered Sunset Village tenants an option: move to Hillside Courts or stay in Sunset Village through the spring semester, after which the village would be closed.

Ultimately Sunset Village closed on August 15, 1972. The university put the buildings up for sale, but only three were sold. The eastern part of the village was bulldozed by mid-September and most of the rest of the buildings were razed shortly thereafter.

Several of the buildings survived for a number of years as storage space and as art studios complete with a kiln. The ceramics studio attracted the attention of the Fire Marshall in 1978, when he ordered the building vacated unless substantial life safety modifications were adopted. The university accepted his order and spent $50,000 to make the old building safer.

So, a collection of surplus metal buildings that was meant to last five years, had lasted over twenty-five years. By the end of their time, most of the buildings were in rough condition. Residents always had their share of difficulties with the buildings, but many students appreciated the value that they received for the affordable rent. As one resident said in 1957, "If it wasn't for Sunset Village, my husband would not be in college today. You can't beat it!"

Compiled by Library Assistant Susan Witthoft; edited by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, September 1996; substantially revised by Gerald L. Peterson, with scanning by Library Assistant Gail Briddle, September 2002; last updated, January 26, 2015 (GP); photos and citations updated by Graduate Assistant Eliza Mussmann April 5, 2023.

"GI Bill®” is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). More information about education benefits offered by VA is available at the official U.S. government website at www.benefits.va.gov/gibill.