World's Fairs and UNI

Introduction

The University of Northern Iowa, situated in the American Midwest, might seem unlikely to have been influenced by or to have participated in major international expositions. However, three world's fairs took place just a day's train or car ride away from Cedar Falls, Iowa: the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1892-1893), the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (1904), and the Century of Progress International Exposition again in Chicago (1933-1934). Many students and faculty visited these fairs, and the school sent exhibits to several of them. In addition, students and faculty visited or took part in other world's fairs farther away from campus. And, in one case, a visit to a fair resulted in the acquisition of equipment for a campus icon.

The term "world's fair" is sometimes stretched to include a wide variety of international expositions. Most people can think of a few of these big expositions without much difficulty, but liberal definitions may go so far as to count thirty or forty world's fairs over the last 150 years. There is even an international agency, the Bureau International des Expositions, that attempts to regulate the frequency and quality of international expositions. This bureau's working definition of a world's fair or exposition includes "all international exhibitions of a non-commercial nature (other than fine art exhibitions) with a duration of more than three weeks, which are officially organized by a nation and to which invitations to other nations are issued through diplomatic channels." The bureau goes on to say that these expositions should be more than trade fairs; they should have cultural and educational value as well.

This short essay will take a conservative approach to the definition of a world's fair, and, in any case, will consider only those world's fairs for which there is documentation of some sort of connection to the University of Northern Iowa.

Note on institutional names. The University of Northern Iowa has had four names: Iowa State Normal School (1876-1909); Iowa State Teachers College (1909-1961); State College of Iowa (1961-1967); and University of Northern Iowa (1967-present). This essay will use the name that is appropriate to the historical era under discussion.

The Centennial Exposition

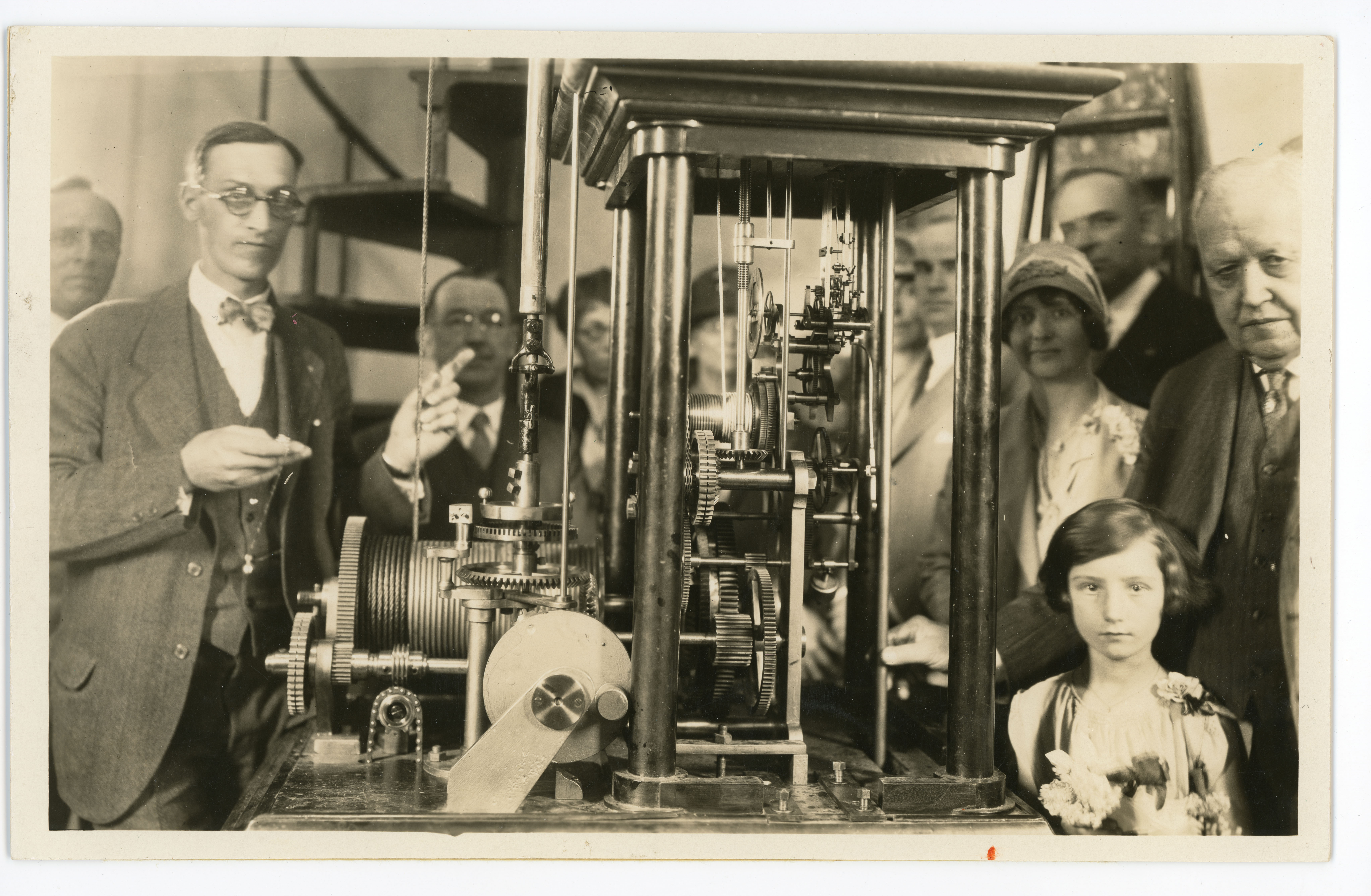

The Centennial Exposition was held in 1876 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The Exposition opened on May 10, 1876, four months before the Iowa State Normal School held its first class. It might seem unlikely that the Normal School would have any connection with an exposition that was held in a distant city before the school even opened its doors. However, in an odd quirk of history, a visit to the fair by a future president of the school would result, fully fifty years later, in the significant enhancement of a campus landmark.

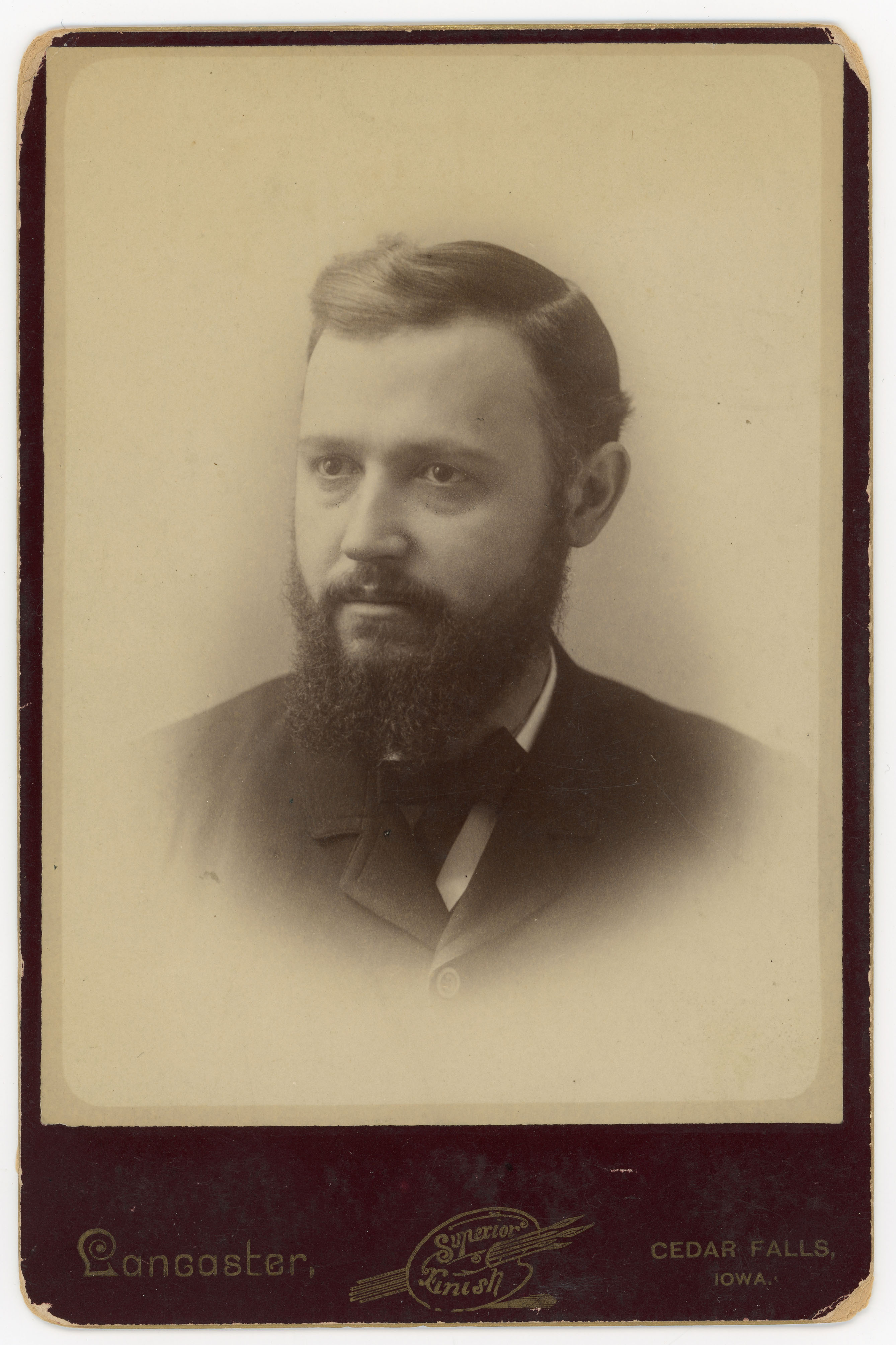

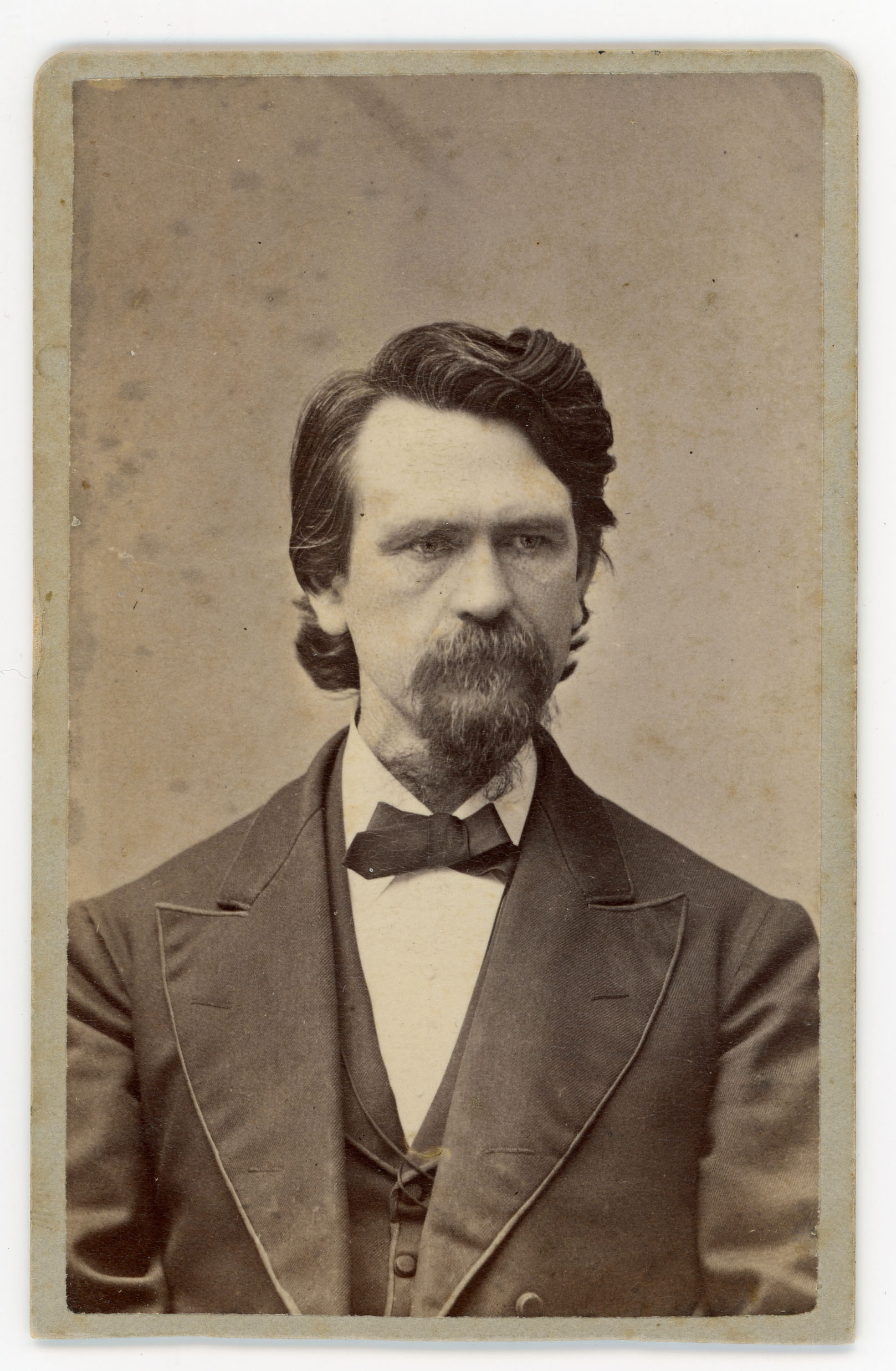

Homer H. Seerley was the Superintendent of Schools in Oskaloosa, Iowa, when he visited the Centennial Exposition in the summer of 1876. Among the many exhibits that he saw was a prize-winning clock mechanism built by Charles Fasoldt of Albany, New York. Ten years later, in 1886, Homer Seerley was selected to be the head of the Iowa State Normal School. He was still President of the school nearly forty years later, in 1925, when the fundraising effort for constructing and equipping the Campanile was reaching a critical point. President Seerley recalled seeing the clock mechanism at the 1876 exposition. Professor A. C. Fuller, chairman of the Campanile Committee, learned that Charles Fasoldt had died. However, the clock mechanism was still in the Fasoldt family's possession. What's more, the family was in the process of looking for a permanent home for the mechanism. They wanted to present it "to the institution or municipality that could afford it the best setting." President Seerley and Professor Fuller deputized former faculty member James Owen Perrine, who worked for the American Telephone and Telegraph Company in New York, to visit Albany and make the case that the Iowa State Teachers College campus would be the best location for the clock mechanism.

Professor Perrine apparently made a strong case. The Fasoldts agreed to place the mechanism in the Campanile when it was completed. The student newspaper, the College Eye, breathlessly announced the donation in its March 18, 1925 issue, where it was described as "the world's best tower clock" with an accuracy of ten seconds annually. President Seerley stated that the Committee had planned to spend between seven and ten thousand dollars on a clock mechanism. Consequently, the gift was most welcome.

The clock mechanism arrived on campus in early November 1926, but college officials had difficulty in contacting Dudley F. Fasoldt, who was to install it. It turned out that several parts had been damaged in preparing the mechanism for shipping. Dudley Fasoldt drove the replacement parts from New York to Cedar Falls and installed the clock in May 1927.

Thus, fifty-one years after the Centennial Exposition closed, a legacy of that exposition was in place on the Iowa State Teachers College campus.

World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition

The World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition was held in New Orleans from December 1884 through May 1885. Nearly all of the states and territories sent exhibits to this fair, which attracted about six million visitors during its run.

The Iowa State Normal School sent exhibits to New Orleans as part of an extensive Iowa display. The Iowa material was shipped to New Orleans in train cars. En route, two cars, containing many county exhibits and a large quantity of women's work, were destroyed in an accident. But the educational exhibits reached New Orleans successfully.

At this point it is unclear exactly what those exhibits were. However, the material likely was quite similar to the collection of "maps, relief forms of the continent, charts, drawings, herbaria, volumes of examination papers on the several objects taught, (and) theses" that the school sent to a national education meeting in Madison, Wisconsin, in August 1884, just a few months before the New Orleans fair.

Normal School Principal James Cleland Gilchrist notes in his 1885 report to the school's Board of Directors that the exhibit sent to New Orleans "was deemed by good judges among the best in the great collections." Noting his state's achievements at the fair, Iowa Commissioner Herbert S. Fairall stated, "In the educational department was her greatest triumph as shown in her numerous awards."

The World's Columbian Exposition

For the first three decades of the twentieth century, when Midwesterners talked about "the world's fair", they usually meant the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. The exhibits at this exposition, which commemorated the four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas, produced lasting effects in art, architecture, industry, technology, and education. About 27 million people, a quarter of the population of the United States, visited the fair. For the Midwest and for much of the rest of the United States, the fair was THE tourist destination of 1893. Practical and affordable automobiles were still a few years in the future at that point. But Chicago was a railroad hub, so transportation to the city was relatively easy and inexpensive. Many railroads even offered special excursion rates to the fair.

The earliest campus references to the Columbian Exposition appear in the January 12, 1892, issue of the student newspaper, the Normal Eyte. Local photographers Lancaster & Corey had displayed a series of photos of the Normal School campus at the annual convention of the Iowa State Teachers Association in Des Moines in December 1891. These photos showed exterior views of campus buildings as well as interior views of rooms, laboratories, and the library. They also showed apparatus from "natural philosophy", that is, science education, classrooms. These photos are among the very earliest surviving images of campus interiors. This series was well-received at the Teachers Association convention. The student newspaper looked forward to displaying them again: "When it comes to World's Fair exhibit(s) the I. S. N. S. will not be in the shade." Just a month later the student newspaper passed on the exciting speculation that a "traveling sidewalk" was being considered as a possible means of transportation around the fairgrounds.

Some of the Lancaster & Corey photos, 1891.

The fair was supposed to start in 1892, which was, after all, the four hundredth anniversary of the first Columbus expedition. Delays in constructing the extensive fairgrounds and exhibits forced most events into the summer of 1893, but dedication ceremonies were held October 20-22, 1892.

The October 11, 1892, issue of the Normal Eyte noted that Helen Hearst, an alumna who was principal at Toledo, Iowa, was visiting her home in Cedar Falls while her school was closed due to the opening of the fair. In that same issue the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern Railway advertised a round trip excursion fare of $11.20 from Cedar Falls to Chicago for the dedicatory ceremonies.

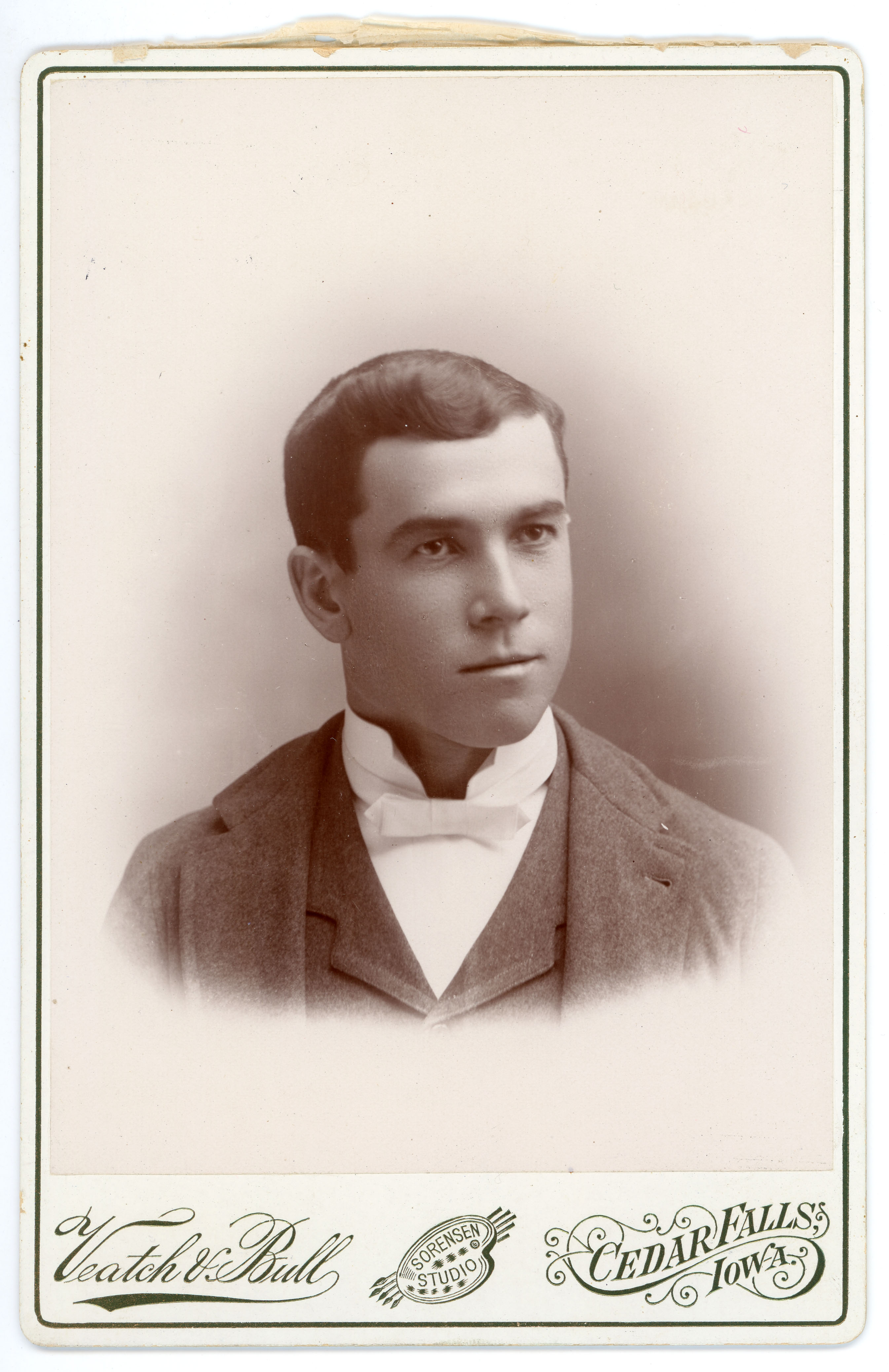

Those who attended the Iowa State Teachers Association convention in December 1892 saw a preview of Iowa educational exhibits that would be going to the fair. The Normal School would have three hundred square feet of exhibition space at the fair, over one-sixth of the space allotted to education in Iowa. The February 11, 1893, issue of the Normal Eyte stated that Cedar Falls photographers Veatch and Bull were taking photos of the ISNS campus for the fair.

At this point it is not clear whether the Veatch and Bull photographs, the Lancaster & Corey photographs, or both series were displayed at the fair. Examples from both of those series have survived in the University Archives.

There was news of the fair in just about every issue of the student newspaper in the spring and fall of 1893. In the March 11 issue, a promoter pitched his Hotel Endeavor as being close to the fairgrounds on a beautiful site near Lake Michigan. What's more, he required no advance deposit for reservations at his hotel. The next issue states that the physics laboratory on campus had been transformed during the winter term into a workshop for the preparation of exhibits for the fair. Physical science professor Abbott C. Page was to have accompanied the exhibit, featuring over fifty photos, to the fair. However, he became ill and student Leslie Chapman was deputized to accompany the material to Chicago. Senior student Charles A. Frederick, who would later join the school faculty, went to Chicago to help Mr. Chapman arrange the material.

By May 13, 1893, J. W. Jarnagin, a member of the school Board of Directors, reported that the Normal School exhibit was well-arranged under glass at the fair. Normal School President Homer Seerley was among the first people from campus to visit the fair. Student Maude Humphrey, who would also later become a member of the faculty, was reported as another early visitor. Perhaps she met former student Fred H. Dawson, who was serving as a fair guide, on the grounds. Allie Richardson, Class of 1892, reported that she had been married recently and that she and her new husband would spend part of their wedding trip at the fair. The last issue of the Normal Eyte for the spring term of 1893 reported that thirteen of the sixteen faculty members who were interviewed about their summer plans included a visit to the fair in their schedules.

When school resumed in September 1893, the editorial writers in the Normal Eyte reported that there had always been two standard questions that students had asked each other: "Where are you from?" and "How do you like the Normal?" After the summer of 1893, however, there was a third standard question with which to open conversation: "Did you go to the World's Fair?" Apparently the odds of receiving an affirmative answer were good. Students, student groups, students and their families, alumni, and others reported on their visits. Some alumni came from as far away as California, stopped to visit campus acquaintances, and went on to the fair. There was a special flurry of activity as the fair run neared its end on October 31. The railroad cut its rates to about one cent per mile. And the public responded. October 9, 1893, promoted as "Chicago Day", saw 716,881 people enter the fairgrounds. It would be interesting to know how many of those fairgoers were from the Normal School. Just ten days before it closed, at least nine students were reported as being at the fair. The editor of the "Local" news column of the Normal Eyte speculated that there would not be much to put into her column once the fair was over.

By mid-November the Normal School display material was back on campus. While many of the photographs have survived to this day, the handiwork and physical apparatus have not. The Normal School won an award for its exhibition at the fair: "Evidence of excellence, first in the construction of valuable physical apparatus, Second in the instruction of young men and women for the profession of Teaching." President Seerley received a bronze medal and an engraved document incorporating this citation of excellence in 1896.

As late as 1900, the Normal School library reported that it had added several volumes on Iowa's participation in the Columbian Exposition to its collection. This world's fair was an extraordinarily successful cultural event shared by millions, including many in the Normal School community

The Pan-American Exposition

At least one Normal School alumnus, Theodore A. Gerard, Class of 1897, visited the World's Fair in Paris, France, in 1900. And two of the literary societies, the Neotrophians and the Ossolis, devoted programs to France and the fair in 1900 as well. But a trip to Europe was beyond the reach of most Normal School faculty and students of that day. So a greater number of Normalites visited the Pan-American Exposition, which was held in Buffalo, New York, from May 1-November 2, 1901. This fair highlighted leading-edge technologies, especially those associated with the use of electricity.

William B. Bell, Class of 1899, who was doing research during the summer of 1901 at Woods Hole Oceanographic Laboratory in Massachusetts, visited the exposition. Mr. and Mrs. E. B. Wilson, Class of 1890, stopped in Buffalo on their way to Europe. Millicent Warriner, a stenographer in President Seerley's office, visited the East and went to the exposition.

Unfortunately, the Pan-American Exposition may be remembered best today as the place where President William McKinley was fatally wounded.

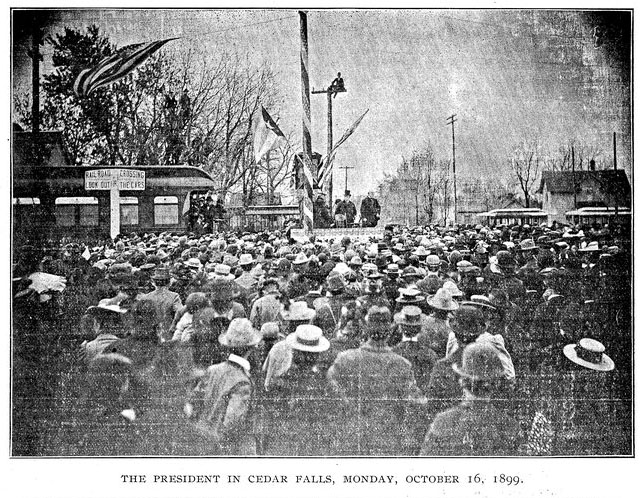

President McKinley held a special place in the hearts of many Cedar Falls citizens. He had made a short stop and speech in Cedar Falls several years earlier on October 16, 1899. The student newspaper of October 21, 1899, reported in an understated tone on that brief local appearance:

"Long before daylight Monday morning horns and guns awoke all sleepers on Normal Hill. At 6:30 the cars started through the rain. Most of the people from the hill went down to see President McKinley. After a long wait in 'pressing circumstances' they were rewarded. The president made a three-minute speech on 'Our United Country.' Recitations began at 8:45 and all settled down to work with a deeper respect for their country and her president."

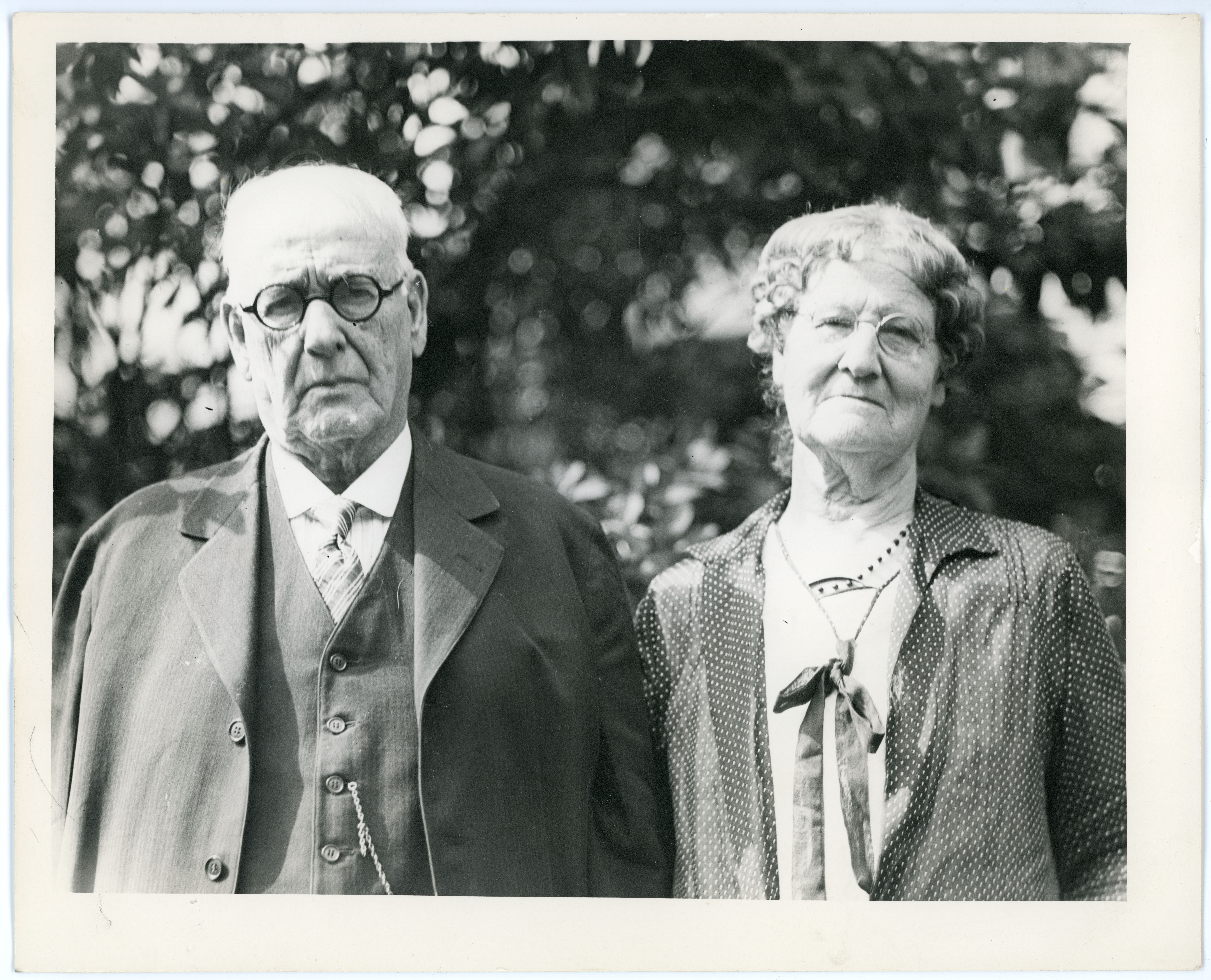

Professor and Mrs. David Sands Wright returned from a trip to the Pan-American Exposition in early September, just in time for the beginning of the fall term.

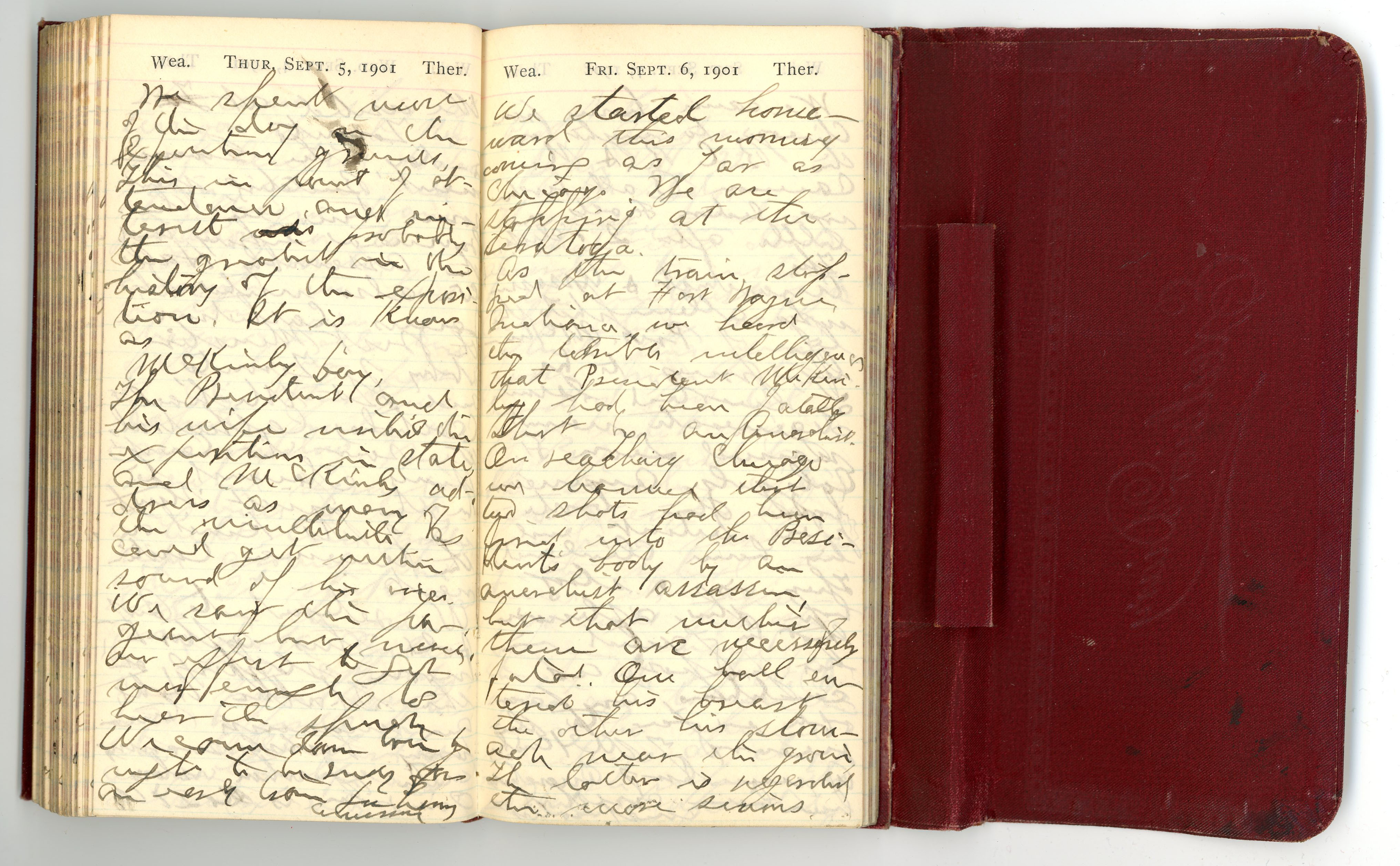

Professor Wright wrote about the trip from Buffalo in his diary on September 6, 1901: "As the train stopped at Fort Wayne, Indiana, we heard the terrible intelligence that President McKinley had been lately shot by an anarchist. On reaching Chicago we learned that two shots had been put into the President's body by an anarchist assassin, but that neither of them are necessarily fatal."

Despite an initially optimistic prognosis, President McKinley died of gangrene eight days after being shot. Normal School classes were canceled so that students could attend memorial services in churches around the community.

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition

The next big fair in which Normal School faculty and students participated was the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, from April 30-December 1, 1904. The proper year to celebrate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase would have been 1903, but, like the World's Columbian Exposition, this fair was delayed one year. The exposition coincided with the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis. Already in December 1902 there is a reference to the fair in the student newspaper. Bloomer B. Rice, Class of 1893, won a chess competition which entitled him to play against world masters at the upcoming fair. Mr. Rice, however, was satisfied with his victory and declined the invitation. In the spring of 1903, the newspaper reported that students at the Hillman school, under the direction of alumnus M. E. Logan, were saving their money for a trip to the fair.

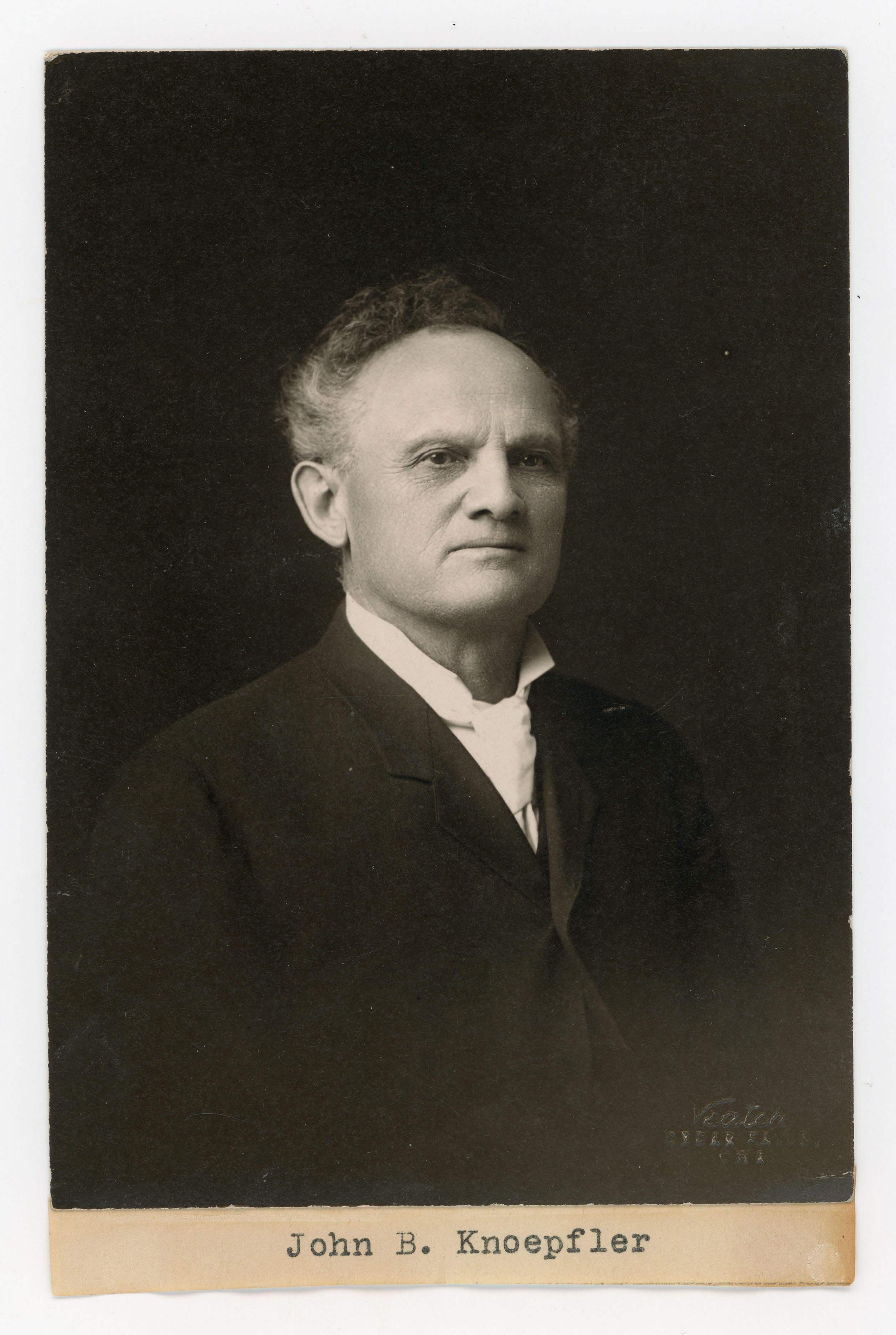

In February 1903, Professor J. B. Knoepfler, of the Normal School German faculty, attended a meeting in Cedar Rapids to decide what kinds of Iowa school exhibits should appear at the exposition. When Professor Knoepfler took charge of putting together the Normal School exhibit for the fair, he drew upon the school's experience with the Columbian Exposition. By March 1904 Professor Knoepfler had shipped the Normal School exhibit to Cedar Rapids, the staging area for Iowa education exhibits. The Normal School exhibit consisted of five parts. Part A consisted of seventy-four photographs of the campus, its facilities, and its people. Part B consisted of six charts that documented the growth and enrollment of the school. Part C consisted of forty-four textbooks published by the faculty. Part D consisted of school publications such as catalogs, reports, and the student newspaper. And Part E consisted of programs, diplomas, and forms.

By the fall of 1904 there was a steady stream of news related to the fair. Student Nina Grau went home to Toledo to visit her sister, who served as a commissioner from Alaska to the fair. Several of the literary societies, the Shakespeareans and the Aristotelians, gave programs related to the fair. Head Librarian Anna Baker and secretary Anna Wild returned from visits to the fair.

As the fair drew to a close, there seemed to be a rush to get to St. Louis. Some students and faculty left school for the fair at the end of the fall term, which concluded around Thanksgiving in those days. The student newspaper of November 23, 1904, reported that at least thirty people from the Hill had gone to the fair that week. President and Mrs. Seerley waited until near the end of November to make their trip. Likewise, a group of young men including William Brandstetter, N. B. Knapp, and Emery E. Magee, received an excuse to miss class so that they could attend the fair.

In the spring of 1905 several of the literary societies included programs with themes relating to the St. Louis exposition. This fair, like the Columbian Exposition, proved popular with the Normal School community probably because of its proximity to Cedar Falls and because of the school's participation in the exhibitions.

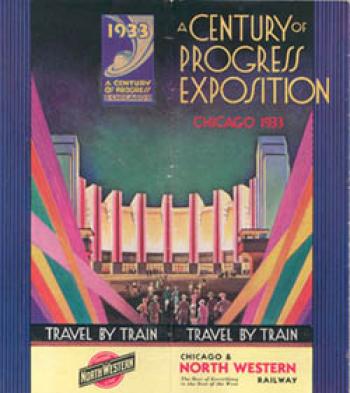

The Century of Progress Exposition

Local participation in world's fairs over the next several decades was relatively slight. The student newspaper notes in November 1915 that a local boy, Parker Lichty, won a contest by raising the then astonishing yield of 102 bushels of corn per acre. His prize was a trip to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. The contest was supervised by Professor Harry Eells of the Teachers College rural education faculty. Several months later, in January 1916, the College Lecture and Entertainment Committee announced that it would be showing a movie about the San Francisco fair. Motion pictures were still a novelty on campus at that time; a screening like this, which brought to life news from distant places, was an excellent use of the relatively new medium. And, in one remote connection of world's fairs to the Teachers College, New York artist William de Leftwich Dodge, who painted the murals in the Library (now Seerley Hall) reading room, was put in charge of color schemes at the Sesquicentennial International Exposition in Philadelphia in 1926. This significant appointment confirmed the wisdom of the Board of Education and President Seerley in choosing Dodge to paint the reading room murals just a few years earlier.

The next exposition to make a big impact on the college community was the Century of Progress International Exposition held in Chicago in 1933 and 1934 to commemorate the centennial of the city. Already in June 1932 a group of Teachers College alumni who lived in the Chicago area met to organize a local chapter of the Alumni Association. Alumni such as Joe Wright, Lee Shillinglaw, and Marguerite Uttley got things started. The new chapter considered various excursions and meetings for the local group itself. However, their initial work aimed primarily at the organization of a nationwide reunion of Teachers College alumni in Chicago in conjunction with Century of Progress activities in the summer of 1933.

Plans were in place by the spring of 1933 when the college alumni magazine announced a schedule for the Chicago events. The Alumni Association would hold a reunion and banquet at the Lake Shore Athletic Club on July 6. Arrangements would be made to see that visitors got a good look at the fair and could even attend the annual convention of the National Education Association during the same visit. A rural school chorus, led by Teachers College faculty member Charles A. Fullerton, would cover the same ground: they would perform at both the fair and the NEA meeting. Professor Fullerton would demonstrate his teaching technique of sending recorded music to rural schools, having the schoolchildren sing along to the recorded music, and then bringing the children together to perform as a mass chorus. Probably for logistical and financial reasons, Professor Fullerton could not take a mass chorus of a thousand children to Chicago. Instead, he took only sixty children. However, since the children came from different schools located in nine Iowa counties, he could still give a valid demonstration of his method and its results. At the NEA convention, superintendents from schools systems outside of Iowa were impressed. Many of them vowed to try to incorporate the Fullerton method into the curriculum of their own states. Following its performance at the NEA convention, the chorus went to the fairgrounds, where they performed in the Hall of Science.

Students and faculty began making trips to the fair in the late spring of 1933 and did not stop until the fair closed in the fall of 1934. Professor Paul Bender took a group of young men to the YMCA camp at Lake Geneva and then accompanied them for a few days at the fair in June 1933. The student newspaper reports that at least six members of the faculty and sixteen students took advantage of the 1933 Fourth of July holiday to go to the fair. Most of the faculty who went to the fair also attended the NEA convention that was being held in Chicago. Edwin Cram, one of the students who visited the fair over the Fourth of July, even wrote a long, if not especially descriptive, column in the student newspaper about his visit. The highlights of his trip seemed to have been meeting other Teachers College students, viewing the Teachers College exhibit, and singing the Iowa Corn Song.

Faculty members who visited the fair had a little more of substance to report. College Financial Secretary Benjamin Boardman compared the 1933 fair to the Columbian Exposition of 1893; he thought that the 1893 fair might have been better in some respects, but that the 1933 fair had much greater educational value. Dean of Men Leslie Reed thought that the fair looked like a "cheapened bazaar" in the daylight, but that it was much better looking at night. He preferred the scientific exhibits to the artistic exhibits. Paul Bender especially liked the scientific and electrical displays. Professor Fred Cram (Edwin Cram's father) and Associate Director of Extension A. C. Fuller were busy with NEA business, but found the fair to have "great educational value" during their brief time on the grounds. An interesting sidelight emerged in the late summer. The college hired John Baker as its head football coach. But, before he reported for work, he would first play in a college all-star football game at the Chicago fair.

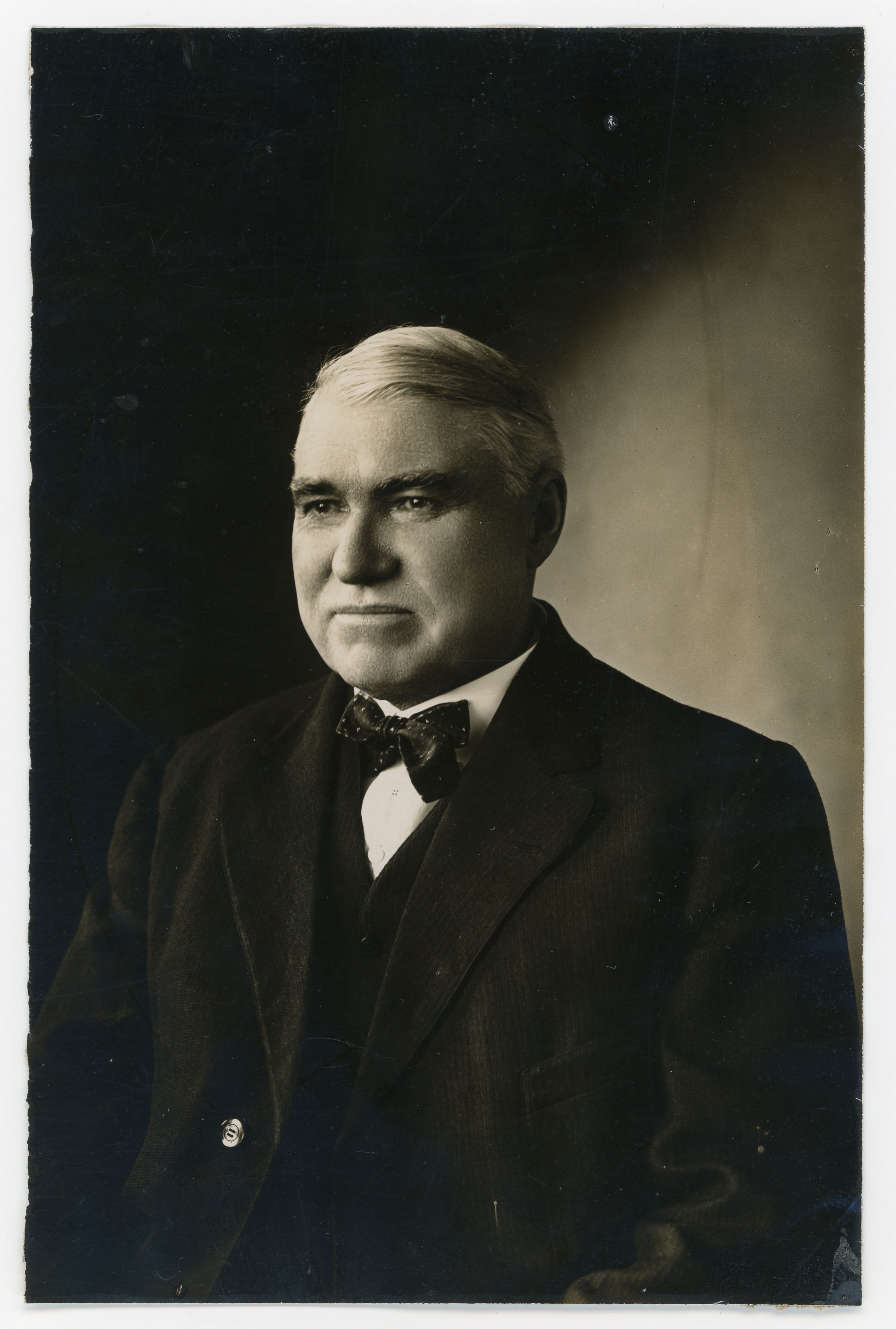

President Latham, his wife Helen, and their children Shirley and Ray made a stop at the fair in October on their way to tour of Canada and the East.

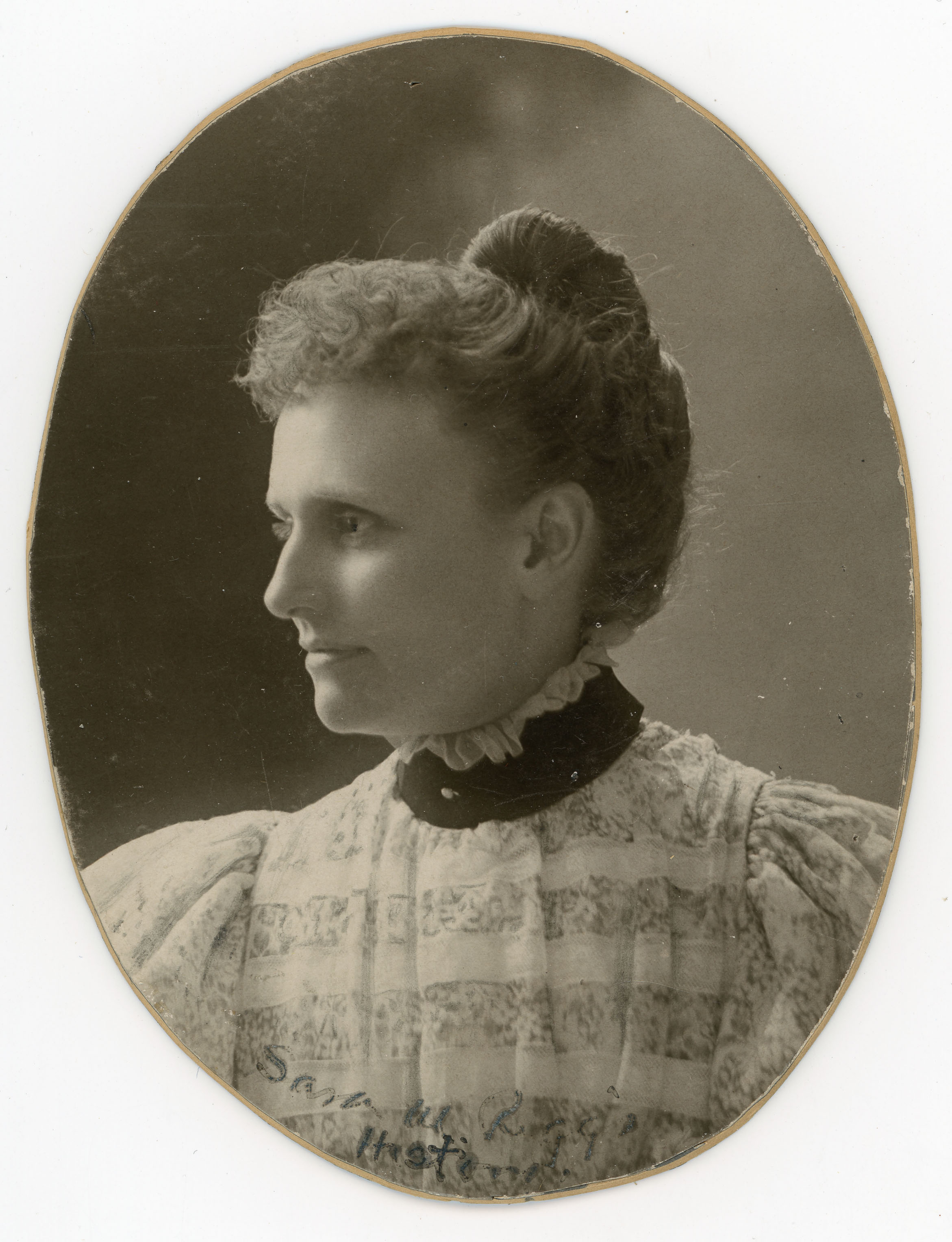

By the fall of 1933, some college people, such as history faculty member Sara Riggs, were making their second visit to the fair. Professor Riggs thought that this fair could not be compared to the 1893 fair since "this deals with science and the former was classical in spirit."

The strength of the science exhibits found its way back to the community in other ways: student James Morehouse made a presentation on "Chemistry at the Century of Progress Exposition" at the campus Chemistry Seminar during the fall term. And a group of local professional and faculty men organized and then named themselves the Arcturus Club, in honor of the star that furnished the light to open the exposition.

News about the fair was quiet during the spring of 1934. Perhaps the novelty had worn off a bit. But things picked up in June. Alta Freeman and Louise Hearst, of the college faculty, visited the fair and found it more colorful than it had been in 1933. Students and alumni such as Betty Severin and Margaret McHugh made the fair part of their summer travel plans. And President Latham and his family made a second visit before the fall 1934 term began.

Early in the fall term the primary classes of the campus school held an "at home" modeled along the lines of exhibits at the fair. These exhibits showed drawings and models of transportation, hand-woven blankets, clay utensils, and other representations and examples of school life. Various parts of the exhibit were introduced and explained by young hosts and hostesses.

In 1935, Jesse L. McLaughlin, Class of 1892, reported an interesting footnote to the fair. Mr. McLaughlin served as secretary to the Chicago Bible Society. His society had sponsored a booth at the fair at which fair-goers could hand copy a verse from the Bible. 31,102 people copied one verse each. Mr. McLaughlin said that the pages would be bound, the names and addresses of the writers would be indexed, and the volume would be exhibited at fairs and conferences.

Historical sidelight. That hand-copied Bible still exists. In a communication to the author of this essay in August 2005, Jannie L. Evans, of the Chicago Bible Society, wrote:

"Our records show the handwritten Bible was prepared at the Chicago World's Fair "Century of Progress" in 1933-1934. The Bible Society's exhibit in the Hall of Religion at the fair attracted wide attention and interest. Visitors were asked to copy a single verse of the Bible on specially prepared sheets of fine ledger paper. As more and more people copied verses and told their friends of the idea, people literally stood in long lines for the privilege. The 31,102 verses in the Bible were handwritten by that many individuals. Every State in the Union and fifteen foreign countries are represented by the writers. The sheets were carefully edited and double indexed and bound. The gigantic task of binding such a Bible was done by Ernst Hertzberg and Sons, Chicago, Illinois. I found located a $1,000.00 transportation insurance policy on the Bible for the period 11/26/37 - 11/26/38 and another for 11/26/38 - 11/26/39. The policies described the property as "One 'Great Bible' authorized version, written longhand by 31,102 different persons, leather bound, in one volume size about 21 inches by 26 inches, approximately weighing 73 pounds."

"The Bible was retained at the Bible House in Chicago until 1976 at which time it was placed on loan to the American Bible Society in New York where it could be given proper care along with other valuable rare Bibles. It is still retained by this Society."

The Century of Progress International Exposition was an extraordinary success in the Teachers College community. Its proximity to Cedar Falls meant that people could get there easily by either train or automobile. Its chronological proximity to the Columbian Exposition meant that older members of the community could visit the Century of Progress and compare it to the 1893 event. The growth in the city of Chicago meant that Teachers College students and faculty could combine a trip to the fair with other activities such as attending the opera, participating in a national educational convention, visiting museums and aquariums, or even taking a master class with a prominent musician.

It is interesting to note parallels between what people saw at the Century of Progress and what happened in Teachers College campus architecture immediately afterward. At the fair, people saw many structures built in the relatively new, streamlined, Art Deco style. And by 1935, the year after the fair closed, Baker Hall, a monument to the Art Deco style, was under construction. It would be an exaggeration to say that members of the college community went to Chicago, saw the streamlined buildings, came home, and immediately decided to build a dormitory in the Art Deco style. The development and construction of public buildings are never that simple. But it seems likely that Board of Education architect Oren Thomas and college officials were influenced by styles displayed in Chicago. Or perhaps the Chicago display persuaded them that the new styles were indeed acceptable and practical, with interesting futuristic elements. The spare, unadorned style also tended to fit the depressed economy of 1935. Whatever the exact relationship between the fair and the new campus style, buildings constructed on the Teachers College campus during the middle 1930s would have looked right at home on the Chicago fairgrounds.

Art Deco features of Baker Hall

Later Fairs

The Century of Progress was the last world's fair to achieve widespread popularity among Teachers College faculty and students. Thereafter, references to and participation in world's fairs were quite limited.

In the spring of 1939 there were two dances held on campus with themes relating to the New York World's Fair to be held in 1939 and 1940. On April 7, 1939, Pi Tau Phi held a dance that featured "Modernistic dance programs and rays of light playing across the dance floor" that were thought to relate to the fair's theme. Just a week later the United Student Movement presented their Spring Fling at which "concessions will be patterned to represent countries having exhibits at the fair." In the fall of 1939 the Marching Band used symbols from the New York World's Fair, the Trylon and the Perisphere, in their final formation at the football game on September 23, 1939. While in that formation, the band played "Sidewalks of New York" and "The Dawn of a New Day."

It was nearly two decades before there was another flurry of activity about a world's fair. In 1958, student Patricia Maxwell was selected as one of about three hundred college student guides in the American Pavilion at Expo '58 in Brussels, Belgium. Among the criteria for selection was the ability to speak French fluently. Patricia Maxwell hurriedly left campus for Brussels in April 1958, just five days after she learned of her selection.

She wrote back to the student newspaper to give her initial impressions. She found her living conditions a bit rough, but with a view of the fairgrounds and the Brussels neighborhood that more than made up for any inconveniences. She found her translation work hard and had occasional difficulty in being understood, but she looked forward to her experience. She spent a great deal of her time directing activities at the American Theater.

Slight references appear in the student newspaper to the exposition held in New York in 1964 and 1965. One article noted that discounted tickets were available to students and faculty. Another article criticized the decision to bar an exhibition of contemporary American art from the fair on the grounds that it would provoke controversy.

Ten years later, the Jazz Band, under the direction of Professor Ashley Alexander, presented four performances at Spokane's Expo '74. The band appeared by special invitation and was well-received. As Professor Alexander reported, "Attendance at the fair started out mediocre, but by our second show the amphitheater was almost full . . . By the third show there was standing room only, and by the fourth and last performance the building was absolutely packed."

In 1982 there was a world's fair in Knoxville, Tennessee, organized around the theme "Energy Turns the World." One descriptive article about the fair, which may have been gleaned from press releases rather than personal observation, appeared in the student newspaper. In the fall of 1982, Professor Ron Bro, well-known for his expertise in energy matters, spoke about the fair at a meeting of Epsilon Pi Tau, the industrial technology honorary society.

The last world's fair that gained any significant attention on the UNI campus was the Louisiana World Exposition held in New Orleans in 1984. After Director Robert Ritschel sent performance recordings to the fair entertainment board, the Women's Chorus was invited to perform there.

Before leaving for the fair, the chorus presented a preview on campus. They performed several numbers with a river theme to go along with the theme of the fair, "Fresh Water, a Source of Life." They also performed tunes appropriate for the Louisiana setting: "Alexander's Rag-Time Band" and "Basin Street Blues."

Summary

World's fairs have had a surprising impact on the UNI community, especially in the early years of the institution. Several of the early fairs gave the young institution opportunities to show the world what the school had accomplished. Developing displays for these fairs was good for school spirit and institutional pride. Visiting the fairs exposed faculty and students to new ideas, technologies, people, and styles. Again and again fairgoers refer to the educational value of their visits. But it would be a mistake to ignore the social, entertainment, and community-building aspects of the whole experience. Getting ready for the fair, going to the fair, and then talking about the fair gave people something to do. At a time when mass communication was limited, the fairs provided a common, generally beneficial experience that was shared by large numbers of students, faculty, and local citizens.

Compiled by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, with scanning by Library Assistant Gail Briddle, July-August 2005; last updated, May 2, 2014 (GP); photos updated and citations added by Graduate Assistant Eileen Gavin, May 9, 2025.