Telephone Service at UNI - A History

Introduction

A college campus is sometimes a center for the introduction, use, and development of technological advances. This series of brief essays looks at the introduction and development of various technologies at the University of Northern Iowa. Each essay is arranged in a generally chronological way. There is frequently considerable controversy about the inventors of particular technologies and the exact date on which their work became available to the public.

These essays will not attempt to settle those questions. Rather, these essays will tend to follow generally accepted historical evidence and practice. Likewise, these essays, for matters specific to the University of Northern Iowa, will simply present readily available evidence. The writer of these essays welcomes corrections and additions.

Telegraph service, which had played a significant role in the American Civil War, was already long established when the Iowa State Normal School, now the University of Northern Iowa, opened in September 1876. Telegraph messages were quick, efficient, and generally accurate. But they did not include the sound of the human voice, with its meaningful tones and immediacy of response. There was clearly room for improvement in communication that included direct human voice contact.

Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone in March 1876, shortly before the Normal School opened. A few years passed before a telephone was installed at the Normal School. The first public mention of a telephone on campus appears in the November 1, 1881, issue of the student newspaper, The Students' Offering. Included in general remarks about recent painting, papering, and carpeting projects on campus, the writer says:

One of the most convenient and valuable of the improvements, is the telephone which

connects with the Falls and Waterloo. It saves many weary trips down town for "that little

thing that I forgot."

There are several things worth noting here. First, the writer assumes that his audience already knows what a telephone is; he does not need to explain it. And its function as a great convenience seems already to be understood. Second, service is available to just Cedar Falls and Waterloo. Local companies had apparently not yet linked themselves to other companies. Or, if the service were available, the Normal School chose not to pay a premium for it.

Telephone access policy in those days is not now completely clear. The telephone was likely a single unit in or adjacent to Principal Gilchrist's office. Could a student ask to use it to call a downtown shop about his laundry, a new shirt, a book, or a box of chocolates? This early reference implies, but does not state unambiguously, that students could indeed use the telephone. In any case, all calls would have been monitored closely by Principal Gilchrist and his office staff. Professor David Sands Wright, a member of the original Normal School faculty, later described the telephone as "new and amazing". Even in those early days, the Normal School Board of Directors was concerned about potential telephone expenses. The Board minutes for June 28, 1882 state:

That when it is thought necessary to do or provide such things as the telephone, omnibus

or other articles incurring unusual expense, it shall be the duty of the party or parties to

consult the Board or its committee before acting . . . .

Telephones of that day were scarcely trouble free. Several later references mention problems with the phone. Just a few months after the installation of the telephone, a writer in the The Students' Offering reported that:

Our telephone is out of order. What a pity! It was very handy and could be utilized

for so many purposes . . . .

Again, it certainly sounds as if the telephone was available to students and that they had already come to appreciate its convenience. Several years later, The Students' Offering reported Colonel Pattee's one-sided telephone conversation. Colonel Pattee, the Steward of the Normal School, was in charge of the non-instructional aspects of school affairs, such as food, housing, and buildings and grounds. Telephone service must have been a boon to him. He no longer had to take his buggy downtown to order food, coal, or other supplies. But he ran into difficulty one day in 1884 when he could not seem to make a connection. He was not at all pleased:

Col. P., through the telephone:--

Hello! Hello! (No answer)

Hello there! I'll leave off the "lo" pretty soon.

Implying that a school official was about to use even mildly bad language was daring for the student newspaper in 1884. But that little incident does illustrate that technology could be frustrating.

3.

That same year the student newspaper reported another interesting telephone incident:

A certain lady enjoyed a very interesting conversation, by telephone, with her father (?) not

long since. But the next time that lady receives a call, we predict that Colonel [Pattee]

won't be so anxious to respond.

Two things are noteworthy here. First, the Steward, Colonel Pattee, seems to have had some responsibility for the school telephone. And second, students were finding ways to use the telephone to communicate with friends and family. The clear implication of this brief note is that the young woman was talking with a boyfriend, and not her father. This story goes nicely with other stories in which young women students of that era received visits from male "cousins", whose visits seemed to make the young women much happier than one might expect the company of a cousin to have made them.

The first official mention of telephone expenses appears in the seventh Normal School biennial report, covering the school years 1887-1888 and 1888-1889. Listed under Students Contingent Fund, General Expenses, is the rent of a telephone and regulator: $108.

The student newspaper for February 2, 1892, offered a tantalizing look at the technological future when it reported on something called a Théâtrophone (Theater phone). This service brought the sound of live operatic and musical performances, via a telephone connection, to subscribers such as high end London hotels and private residences in Paris. The editorial writer believed that the technological future was at hand. The writer noted that Edward Bellamy's extraordinarily popular utopian novel, Looking Backward, published just four years earlier, was not as far-fetched as some thought. A bit more than a year later, Normal School student Albert L. Comstock, Class of 1893, wrote a long essay in the student newspaper on technological advancements, including telephone service. The 1880s and early 1890s were a time of anarchists, assassinations, startling new political writings, and turmoil around the world. Mr. Comstock believed that technology, by lightening the drudgery of many kinds of work, could lead to a more settled, peaceful world in which citizens would not be inclined toward radical societal reforms.

In late 1895 and early 1896, there was considerable news about telephone service on College Hill. The school added a second telephone to its offices in November 1895, and several residences in the new College Hill neighborhood had telephones installed later that year. There were also several interesting commercial links to telephone service. The A. C. Wise & Sons bookstore stated that "the telephone in their lower book-room is always at the disposal of any student." Students were clearly the beneficiaries of this excellent marketing strategy. The availability of telephones did have an occasional downside: railroads noted that there was a decline in commercial travel. Companies could conduct business over the telephone instead of traveling to distant points to do business in person. The ownership and regulation of telephone systems was in the public eye. In 1898, the Philomathean, Aristotelian, and Orio Literary Societies debated the question: "Resolved, That the United States should own and control the telegraph and telephone lines."

As the College Hill community grew, so did access to utilities, such as telephone systems. The Cedar Valley Telephone Company erected poles along 22nd and Normal (now College) Streets and installed a "toll station", apparently a public telephone, in the Auld Photography Gallery on the Hill. Wiring on campus progressed, too. In 1901, a private line, akin to an intercom system, was installed between the office of President Seerley and the office of Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, James Robinson. During the first decade of the twentieth century, new construction, supervised by Mr. Robinson, was almost always under way on campus. The telephone connection made it much easier for President Seerley and Mr. Robinson to communicate on important day-to-day matters. President Seerley was a voluminous correspondent; the University Archives holds thousands of his letters. However, he also appreciated the value of telephone service. In 1902, in a long essay on the need to strengthen rural education, President Seerley stated that:

. . . the suburban trolley and telephone lines will bring the farm into close touch with

the intellectual and social culture of the city, and these, with other modern advantages,

will enable the Iowa farmer to take a princely position among the world's workers

and promoters.

Telephone service was becoming more and more of an expectation. A 1905 editorial in the student newspaper called for a telephone in the new Gymnasium, now the Innovative Teaching and Technological Center. At that time, if someone in the Gymnasium received a call, staff from President Seerley's office would need to walk over to the Gymnasium and then bring that person back to the office to take the call. It is unclear exactly when that telephone connection was made, but by 1907, when the first switchboard was installed in his office, President Seerley claimed that the Normal School had "the best clock system, the best interior telephone system, and the best heating and ventilating system" in Iowa.

The "interior telephone system" refers to the wired connection from the president's office to each classroom on campus. If someone wished to contact a student, the call went to the president's office. The office staff then called the classroom where the student was present and requested that the student report to the president's office. It must have been an anxious, embarrassing experience when a professor announced to the entire class that a particular person was to report to the president.

When President Seerley moved into the new President's House in October 1909, there was a telephone on both the first and second floors. However, when Bartlett Hall, the new women's dormitory opened in 1915, telephones were scarce and lines were overcrowded. Contacting one of the three hundred women in Bartlett Hall at telephone extension number 863 was difficult. Student H. C. Sheldon, Class of 1922, wrote a long letter to the student newspaper entitled "Why dormitory girls don't get more dates". The letter describes his many, many attempts, sometimes lasting for hours, to call someone in Bartlett Hall. He concludes his letter by asking:

. . . it does seem mighty strange that the girls of Iowa State Teachers College Dormitory

can't have more adequate telephone service so that their friends might be able to

converse with them without spending so much time, energy and patience in doing so.

Why not a comprehensive system of telephones for Bartlett Hall?

Mr. Sheldon's complaint would be echoed for many years afterward. Students of that era were not asking for a telephone in every room. That was too grand a scheme and too great an expense. They would have settled for a telephone in each wing of Bartlett Hall. A Bartlett Hall resident (or, as she put it, a member of the Old Maids Kingdom) responded to Mr. Sheldon, in a cute little poem:

A telephone in every room

Would bring things out all right!

I'm sure it ought to be arranged.

'Twould make our life more bright!

An editorial in 1923 called for a single Christmas present for Bartlett Hall: a workable telephone system. The editorial compared the chances of contacting someone in Bartlett Hall with the chances of winning a new Ford in a raffle--very, very slim. As of 1927, there were two telephones for the 550 women in Bartlett Hall. Students got no comfort when they learned that the University of Iowa was installing telephones in each room of Currier Hall on that campus. By early 1932, the Teachers College was finally able to respond to the demands for better telephone service in Bartlett Hall. There would still be a central Bartlett Hall number, but the central switchboard would be able to pass on a call to one of sixteen new telephones scattered down the hallways of the dormitory. The news release announcing the new service stated that the five hundred Bartlett Hall women often placed as many as two hundred calls per day, an unimaginably low number by today's standards.

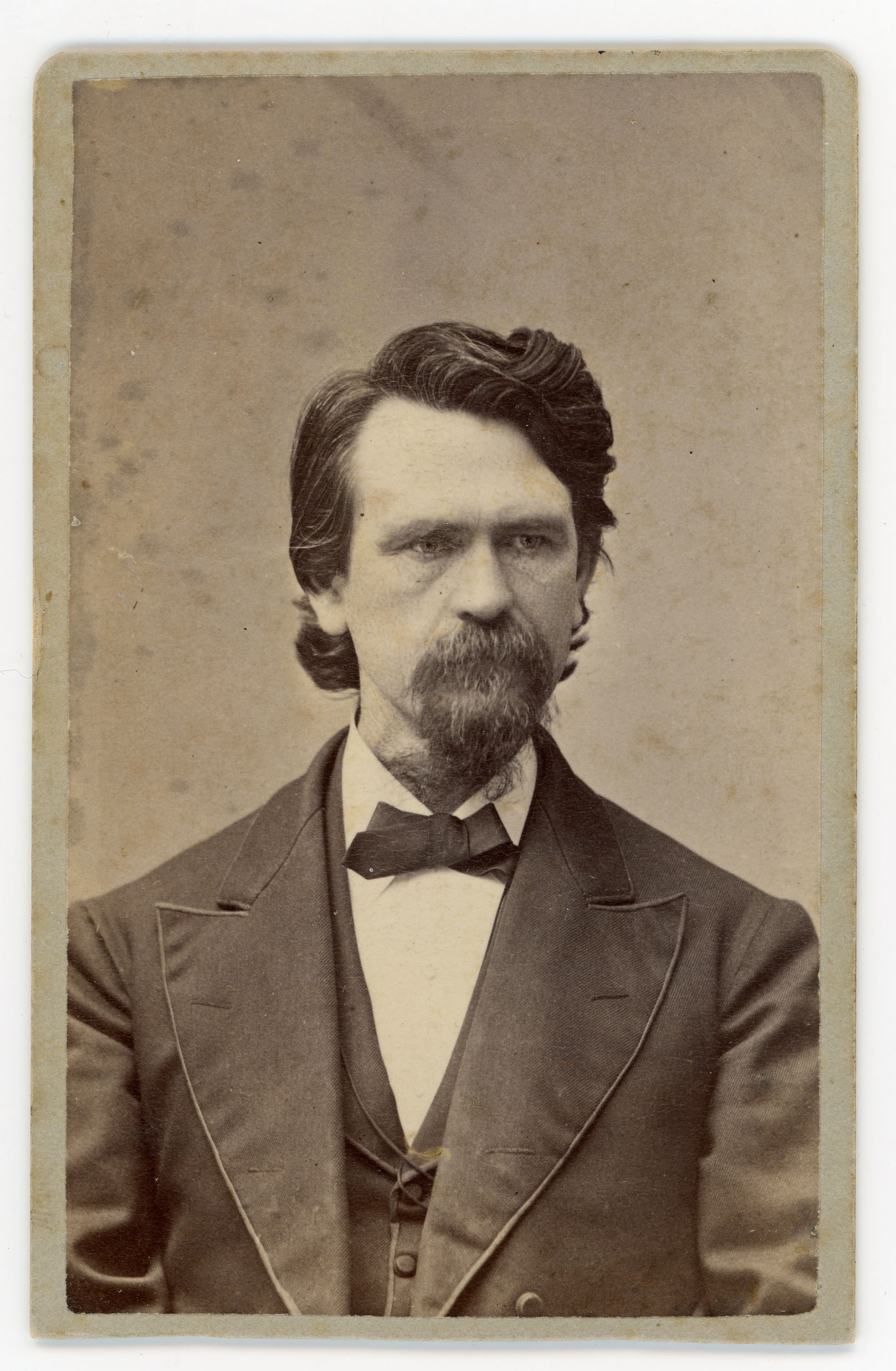

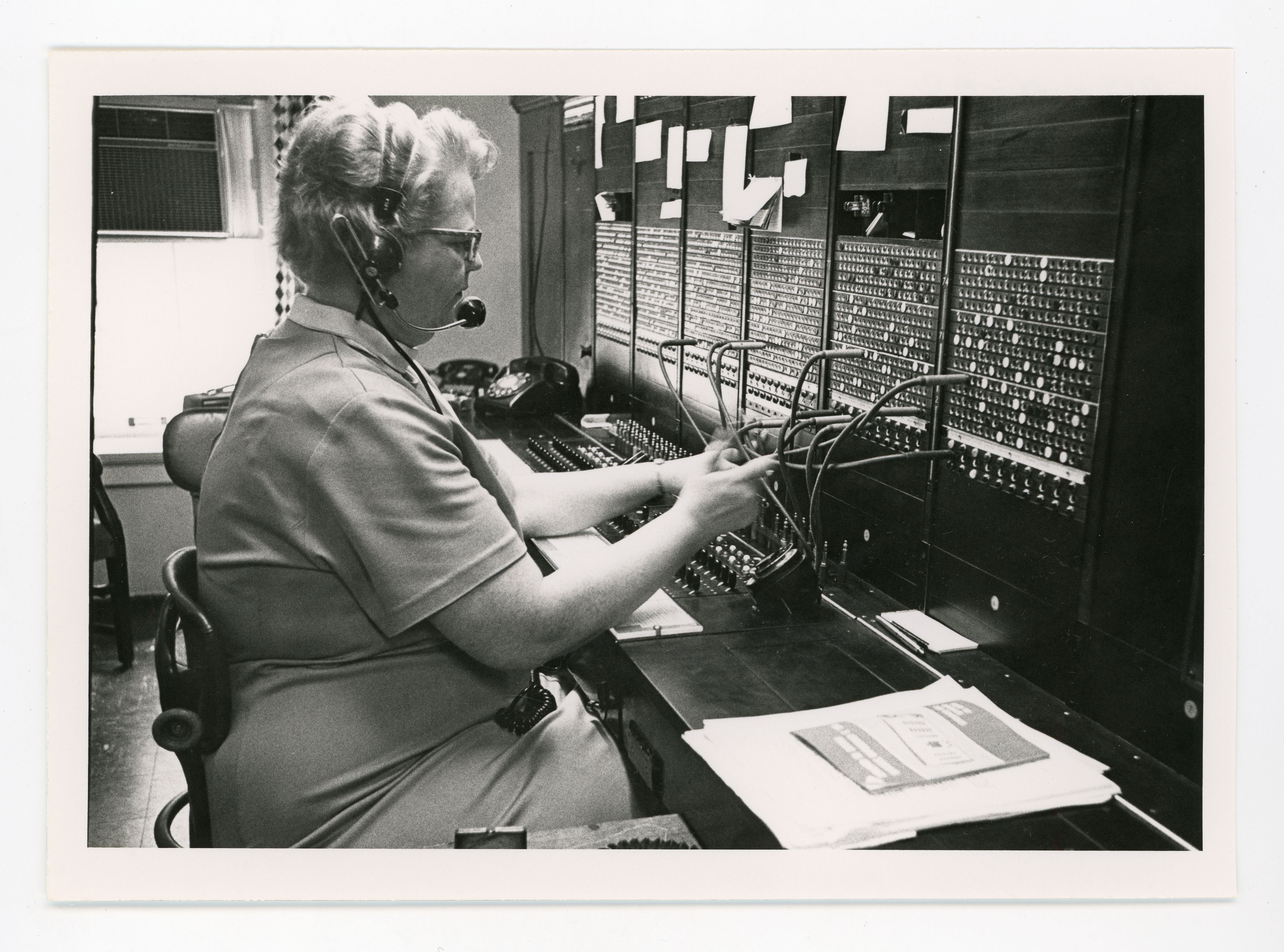

President Seerley had been fairly progressive in his use of telephones, but President Latham, who took office in 1928, was much more so. By 1936, President Latham had doubled the number of lines and telephones. When the Commons was completed in 1933, a second switchboard was installed there. By the summer of 1936, the college had two full-time switchboard operators. Calls were limited to three minutes before operators cut them off. No calls were put through after 8PM. When Baker Hall for Men opened in 1936, it had its own switchboard system, staffed by residents. As telephones became more available, abuses occasionally occurred. One fraternity man made a slug the size of a nickel, the price of a call on a public telephone, and made free calls. He tied the slug to a silk cord and then pulled out the slug to make more free calls. Switchboard operators in the Commons also had to put up with annoying situations. Someone would try to call a friend on campus, but would not know her name. The request would go something like this: "I'm looking for Suzie. Don't know her last name. But she is tall, laughs a lot, and has reddish hair." The operators did their best with these calls.

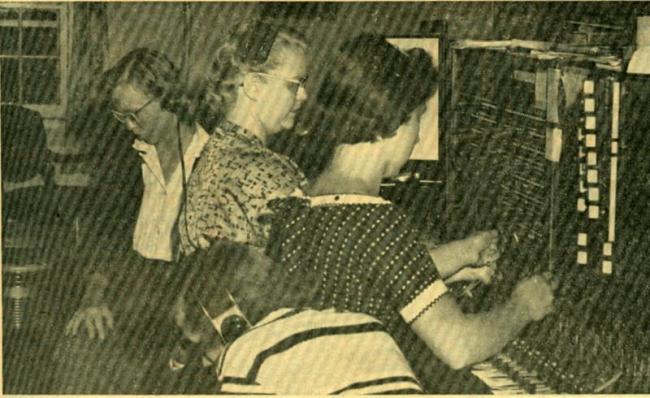

When Lawther Hall opened in 1940, a buzzer system was installed in each room. Operators would buzz the appropriate room to notify a student that she had a call. On February 7, 1947, the college combined its switchboards into one location in the basement of Bartlett Hall. Ten trunk lines led to this switchboard. If someone wished to call off campus, he simply said "outside" to the switchboard operator, and he would be transferred to the downtown operator. The school also printed a small telephone directory at that time. Four full-time operators, assisted by three student employees handled three to four thousand calls per day. The switchboard was open from 7AM until 10:30PM, though the 8PM curfew on calls to Bartlett Hall was still in effect. In talking about her work, one operator stated that "Men have no pride." She said that if they could not contact the first woman whom they were trying to call, they just moved down their list until they found one who was available. Failing that, they asked operators for recommendations!

Postwar enrollment growth put pressure on the campus telephone system. Operators earned the reputation of being very hard workers, but there were occasional complaints about rudeness. Students complained that five minute phone calls were tough, especially when it took five minutes even to get the operator.

By 1951 there was a new, more efficient switchboard staffed by eleven full and part-time operators, who handled about four thousand calls per day. The operators stressed that things would move more quickly if students would have proper names and extension numbers in mind before placing calls. Also in the summer of 1951, Bartlett Hall incoming call privileges were extended to 9:30PM, but only for the relatively quiet summer term. When Campbell Hall opened in the fall of 1952, there was a telephone in every room. That was a first for the Teachers College. Students were happy to pay the slight extra charge for that convenience. While this was a boon to Campbell Hall residents, the increased volume put additional stress on the new switchboard.

In 1954, the city of Cedar Falls inaugurated a dial telephone system. Until that time, the telephone system required operator action for every call. A person would pick up his telephone, an operator would answer "Number, please?", the caller would give the number that he was trying to reach, and the operator would place the call. The new dial system in Cedar Falls would allow callers to place local calls directly. Long distance calls still required operator assistance. The conversion to dial service was a major project for Cedar Falls. Every old telephone had to be replaced with a new dial phone. The first exchange prefix, CO6 (for Colfax 6), survives to this day as the common Cedar Falls telephone number prefix, 266. This upgrade was tantalizing for students on the switchboard-bound Teachers College campus.

Feature articles in the student newspaper continued to note the hard work of the full-time and student operators. But the volume of calls and the small number of telephones made their work very difficult: operators served 545 campus extensions, some of which served as many as thirty people. One 1957 article noted that there were twenty phones for the 511 women in Bartlett Hall; seventeen phones in Lawther Hall for 501 women; and fourteen phones in Seerley-Baker Hall for Men to serve the 441 residents there.

Limited dial telephone service was introduced to campus on March 27, 1959. To place an off-campus local call, faculty and staff offices would first dial 9 and then the direct outside telephone number. Students could reach dormitory corridor phone numbers by dialing 0 and then the corridor extension number. Other kinds of calls still required operator assistance. To place long distance calls, students needed to use public telephone booths on campus.

In 1961, most college campuses were attempting to prepare for the extraordinary increase in enrollment that the Baby Boomers would bring in just a few years. The Iowa Regents institutions were no exception. Everyone agreed that Regents schools would need more dormitories. But there were serious questions about whether or not new facilities should include a telephone in every room. The Board of Regents decided to study the matter. Were telephones simply a convenience? Were shared corridor phones good enough? An editorial in the student newspaper took a clear stand on that matter. The editorial pointed out the difficulty of quiet study when the corridor phone rang constantly. It also noted the sheer difficulty of finding an open telephone to use when a person really needed to place a call. It even reported a poll in which students at Iowa State University had been asked whether or not they favored the slightly higher room and board fee that would be necessary to cover the costs of installation and maintenance of room phones in dormitories. Only thirty per cent objected to the higher fee. The editorial writer urged the Regents to forget their study and to approve in-room phones.

By 1965 Lola Holmes was the school's head operator. She would become almost legendary as the telephone voice of the college. Miss Holmes supervised two other full-time operators and nine student operators. They handled about two thousand calls per day. While the switchboard had the capacity for ten thousand telephone lines, there were only 872 lines on campus. There were twenty-two trunk lines for off-campus calls. The two operators on duty could handle about 150 calls per hour.

The Regents did not heed the advice of the student newspaper editorial writer, nor the clear opinions of other students. When Hagemann Hall opened in 1964, fifteen corridor telephones served about 408 women. Ten additional phones were installed in 1966 to make the problem of busy lines slightly better. At that time, Lawther Hall had thirty-one phones for 550 women, and Bartlett Hall had thirty-six phones for about 625 women. In October 1966 there was a small fire in the switchboard room that caused little damage but did knock out telephone service for a couple of hours.

The call for in-room telephones reached the Regents again in 1967. With call volume up to four thousand per day, something needed to be done. Even college Business Manager Philip Jennings, known for his conservative fiscal practices, said:

This is a necessary move because the present college switchboard is inadequate

to meet the expanding telephone needs of the college.

Campus administrators supported the installation of a new Centrex system at a cost of about $25 per student per year. Some students objected. They believed that the telephone system needed to be improved, but they thought that each student should have the option of whether or not he wanted a phone in his room. On January 13, 1967, the Regents approved the purchase and installation of the Centrex system. All dormitory residents would see a $22 to $25 annual increase in their room and board fees to cover the cost. Officials projected that it would take about two years for the new system to be installed. The Student Senate urged that the existing switchboard be improved and that hours of operation be extended until the Centrex system was ready. The college administration responded by keeping the switchboard open until midnight for a one month trial period.

Installation of the Centrex system was set for the summer of 1969. The new system would allow direct dialing to and from Cedar Falls and Waterloo telephone numbers. Direct long distance dialing would also be possible. The local Northwestern Bell Telephone Company expected to serve about two thousand dormitory rooms and over five hundred administrative lines. Room telephones would not initially be installed in Baker, Bartlett, or Lawther Halls due to both high costs and to the objections of some students to paying the extra charges for in-room lines. Most students eagerly awaited the installation.

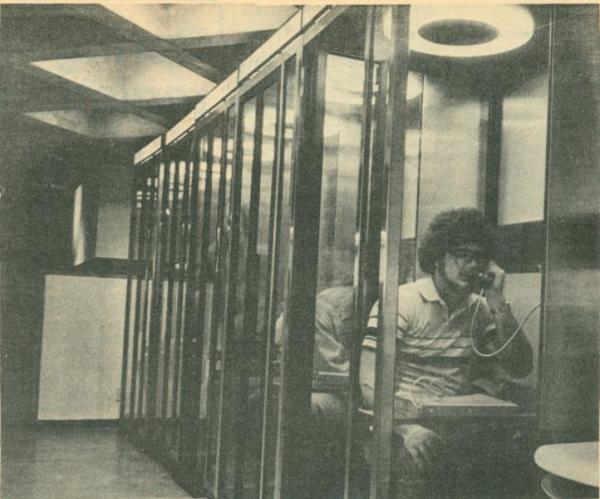

The Centrex system installation was completed on August 24, 1969. The old switchboard was removed, but Lola Holmes stayed on as head of the campus telephone information center in a new room in the Maucker Union. That center received about eight hundred requests for campus information per day. The Union also made a range of public telephone booths available to students, when they were on campus and away from the room phones.

In November 1970, the Union put together "Events Dial", a recorded message offering information about upcoming campus events such as athletics, concerts, dramatic productions, conferences, and dances. In September 1972, the telephone information center moved to the Public Safety Office, where it could be staffed twenty-four hours a day. Miss Holmes stated

We moved to the Security Office so that the dispatch clerks could answer calls when

operators were not on duty. This would help give better security service.

The information center continued to be a busy place, especially in the early part of the fall semester before the campus telephone directories were available for distribution. There were two full-time operators and six students on the center staff. Two operators were on duty until midnight and one operator staffed the phones overnight. They served 3331 campus telephone lines. In 1977, overall administrative costs for campus telephone service--unit rental, long distance charges, installation, maintenance--were about $400,000.

Access to direct dial long distance service led to occasional abuses. Some students ran up such high telephone bills that Northwestern Bell cut off their service. The student newspaper, which formerly ran regular feature stories on the old switchboard operations, now began to run consumer tips on how to reduce costs of long distance calls. In the fall semester of 1977, parts of Bartlett Hall were converted to a co-ed living arrangement. By that time, the corridor telephone arrangement was gone. All rooms in Bartlett Hall had telephones.

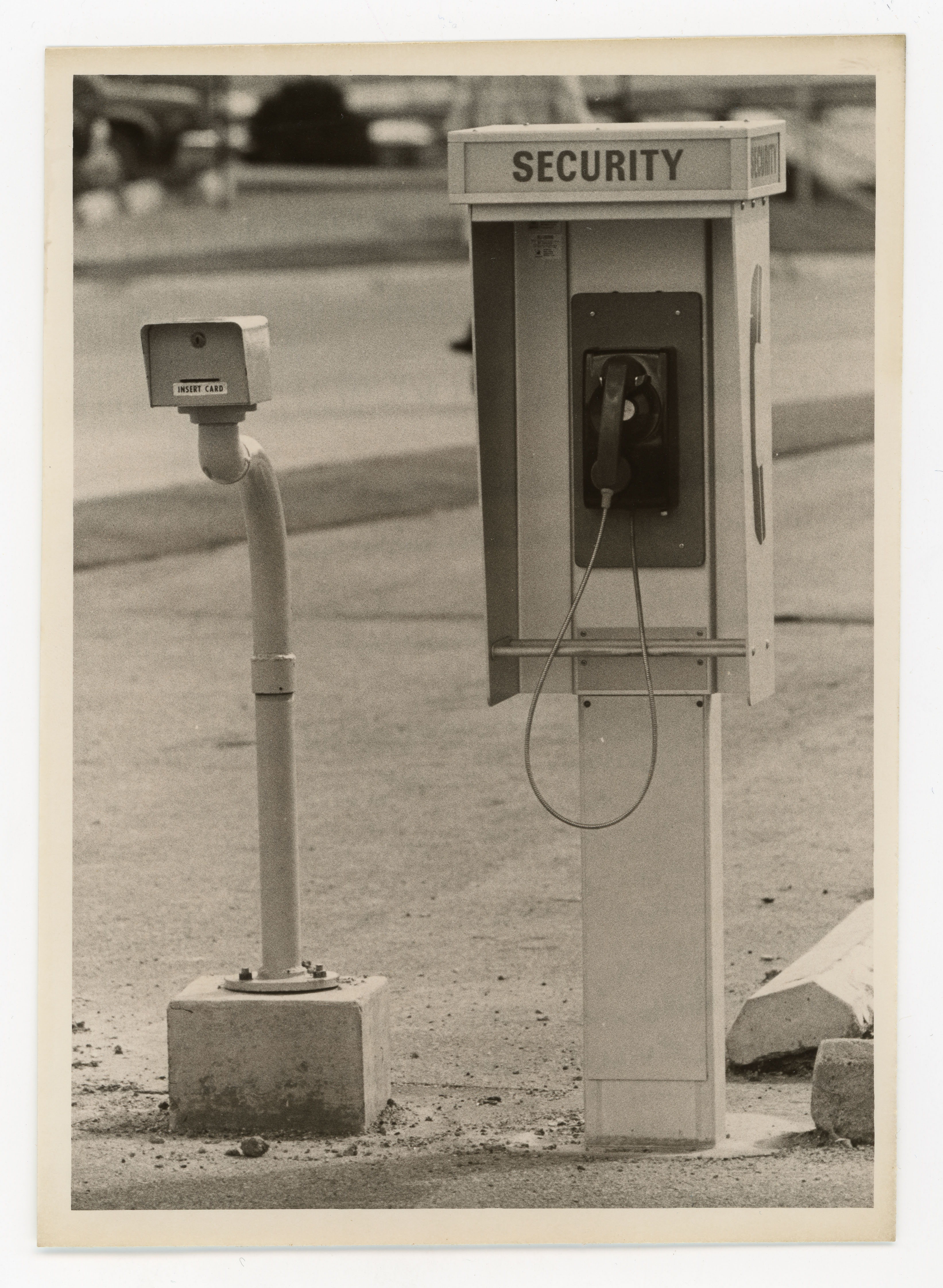

Telephones had long been an important part of the campus security system. Phones were the best means of reporting fires, suspicious activity, and emergencies to the proper authorities. But in the spring of 1978, the university installed its first telephone aimed specifically at campus safety and security. An emergency telephone booth was installed at the entrance of the G parking lot just east of Gilchrist Hall. Rollin Evers, head of Public Safety, stated that the telephone was connected directly to the Security Office.

Mr. Evers thought that the most important use of the phone would be for women arriving on campus late at night or very early in the morning. At that time of day, they would likely be able to find a parking place only at the distant edges of campus lots. If they were concerned for their safety, they could call Security on the emergency telephone and an officer would be dispatched to escort them safely to their destination. That first emergency telephone location eventually blossomed into the current blue light emergency telephone system on campus.

In August 1981, the campus began its switch from rotary dial to touch-tone telephones. The complete campus conversion to touch-tones took over a decade, with some dormitories finally converted in 1992. The Centrex system, which had become inadequate and was plagued by maintenance problems. was replaced by the Dimension 2000 system. Improved cabling accompanied that change. The new system made it easier to forward or hold calls, though there was a bit of learning necessary to understand exactly how to do those things. The new system included sixty-six lines for outgoing calls and sixty-one lines for incoming calls. However, there was at least one potential source of irritation. The new system was powered by electricity. So, if power went down, so did the phone system. There were some initial problems with line availability during peak hours, but adding a few lines seemed to take care of the situation.

Students sometimes had other kinds of problems with telephones. Elizabeth Bingham, a student newspaper columnist in 1985, wrote very well about the telephone as a temptation to waste time. A quick call about an assignment turned into a half hour of chatter about relationships. That call was followed by a long distance call to friends or family. The sequence was then concluded by a pizza order. The ultimate results were a failure to study and a big phone bill. In many ways, Ms. Bingham anticipated much worse telephone problems twenty or thirty years after she wrote her column. But students also had fun with their phones. In the early 1990s, many students installed answering machines and competed with each other to have the funniest messages. Callers might place a call to a friend and find that they had reached "Bob's Bar", "Lucious Larry's Discorama", or "The Singing Nun".

Registration for classes had been a grueling, time-consuming, frustrating activity for just about the entire history of the University of Northern Iowa. But, in 1992, with touch-tone phones available across campus, the Registrar's Office began to study the possibility of moving registration to the telephone. Assistant Registrar Doug Koschmeder stated that if funding materialized, telephone registration might be ready by 1994. Associate Registrar Mary Engen said that registration in person would be maintained as an option for those who did not trust telephone transactions.

By 1996, with the university using about five thousand lines, officials were looking at a new telephone system that would include the capability to carry voice, data, and video, as well as many additional features. The system would be integrated with the university computer system so that a person could check his U-bill, monitor his financial aid package, and even register for classes via the telephone. The new digital system, Definity G3R Enterprise Communications Server from Lucent Technologies, was ready for use on May 30, 1997. UNI Voice Services Manager Randal Hayes said, "We'll have fully digital switching, which will improve current calling capacity into and out of the University. It will also offer a number of new or improved features, including voice mail." Officials hoped to have the entire campus hooked up to the new system by 1998. Any required re-wiring would include hardware that would enable or enhance Internet access as well. By December 1998, anxious students could use the new phone system to check on their fall semester grades. At that same time, the Public Safety Office was using the new system to improve the quality of its radio communications.

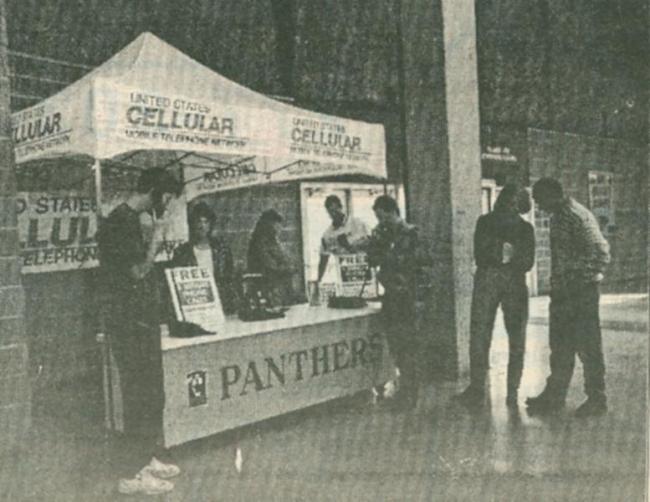

But the next wave in telephones, utilizing wireless communication, was in the air. During the 1996 football season, US Cellular maintained a booth at which students could try the new cellular phones. They could call anywhere in the state without charge during the games. US Cellular also gave cell phones to game day coordinators, who had formerly used hand-held radios to help stage game activities. At that time, the university was again having difficulty maintaining enough landlines for its students. Cell phones had the potential to make that demand diminish substantially. Also, long distance costs were being cut sharply by the use of the Internet and data networks. Digital switches were replacing mechanical switches. The new switches converted voice conversations into data packets, which were then transmitted over the Internet.

Cell phones were a bit slow to catch on at the university. But when they did arrive, they spread very quickly. The writer of this essay only occasionally observed students with cell phones in the late 1990s. But, by the fall of 2000, just about everyone seemed to have one. While most cell phone users cited the value of possessing a cell phone when an emergency arose, they also enjoyed its portable convenience for handling everyday matters. Students enjoyed being able to communicate with anyone, at any time, and in any place. They also soon learned that cell phones could be a problem. Sometimes people preferred to be out of contact; they really did not want to receive communications. But there was their cell phone ringing in their backpack. And, unless a user remembered to turn off his phone, a sudden ring was very disturbing in class and in other formal situations. Many students also used their cell phones for useless conversations that simply passed time as they walked between classes. Was it really necessary, or even useful, to tell friends that they were walking through the Union? One student wrote a sarcastic letter to the student newspaper in which he "thanked" cell phone users for continually disturbing his study in the library and for keeping their ring tones turned on loud and clear. As with most technologies, a certain code of etiquette gradually developed around cell phone use. But even people with good cell phone manners could occasionally forget to turn off their phones.

Still, cell phones were here to stay. Students soon found themselves to be targets of continuous marketing promotions. Cell phone companies wanted to capture the valuable student demographic group. In 2002, US Cellular, through its Community Action Life Line program, donated ten cell phones and airtime to the university to be used in connection with campus security. Associate Director of Public Safety David Zarifis said

U. S. Cellular's C. A. L. L. program will be an integral part of the UNI Student Escort

Program. In addition, the phones will help us partner with other campus departments

involved with programs to prevent violence against women.

Corporate philanthropy such as that likely made a good impression on students.

Cell phones from even ten years ago now seem like primitive devices: unless a user was very sophisticated or had a very high end device, early cell phones were usually limited to placing and receiving calls. But cell phones began to add features that tempted many students to trade up to the continuously evolving generations of phones, usually with additional user charges. By 2005, texting had become popular among young people. Some students liked the quiet aspect of texting. A person could send a message without disturbing others. The person receiving the message could read the text at his convenience. Of course, people soon learned that texting while driving was a very bad idea. And they also began to see that excessive digital communication could be personally isolating: people talked with each other via a digital device rather than in person.

New generations of cell phones were able to access the Internet and even to take photographs. The increasing popularity of social media that were accessible via cell phones made the perceived problem worse. Whether they sent text messages in class, on a walk, or while driving, people were distracted from what the proper object of their attention should have been. Student newspaper columnists repeatedly confessed that they were heavy cell phone users and texters, but they also thought that things were moving a bit too far and too fast in that direction. They noted that the odd abbreviations used by texters seemed to be creeping into formal communication. Texting in class seemed to have become a common practice, even though most faculty members required that cell phones be turned off in class and put away during examinations. Yet the university administration believed that cell phones could be a useful part of the campus security system. When students needed to be informed about important campus matters, such as cancellations due to weather, cell phones were an important outlet for transmitting that information. And at least one columnist noted that, for better of for worse, cell phones cut down on the need to plan things well in advance. A person could set up a date or a meeting with just a few keystrokes of text. By about 2003, cell phones, with their extraordinary capabilities, became an indispensable part of just about every student's life.

Recognizing that the day of land lines for everyday use had passed, the Department of Residence stopped providing in-room telephones in about 2006. Long distance service was discontinued in July 2004. Telephone service itself was removed from dormitory rooms in the summer of 2010.

In an ironic reversal that looks back almost one hundred years, there is now just one land line emergency telephone per floor in the residence halls.

Summary

Communication technology has come a long way on the University of Northern Iowa campus since 1881, when use of the single campus telephone was closely monitored by Principal Gilchrist and his staff. Even in those early days, people quickly learned to value the convenience of telephones, but expectations for access grew relatively slowly. And the ability of the university to meet expectations grew even more slowly. It was not until 1950 that even one dormitory had in-room phones. And it was not until about 1977 that every dormitory had that convenience. By 2014, the most commonly used telephone among the students of the University of Northern Iowa is a sophisticated cell phone. But telephone service is only a small part of the capability of that device. Students can call their parents, make a date, keep up with job prospects, look up a quick fact, check on class assignments, take pictures, listen to music, and do a hundred other things simply by using a small, hand-held device.

Cell phone technology is an excellent example of the way in which many technological tracks merge into a single track. Detailed planning, hard work, extensive training, and large capital outlays went into delivering good telephone systems to the University of Northern Iowa. Those expenditures were necessary to meet the expectations of university students, faculty, and staff. At this point, the sophisticated, wired telephone remains a vital communication tool for the administrative work of the university. However, for personal communication, and for an increasing amount of business, the personally owned, multipurpose cell phone has become the technology of choice for students and for many members of the university faculty and staff.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, with research assistance by Student Assistant Mackenzi Brophy and scanning and research assistance by Library Assistant Joy Lynn, July-August 2014; updated, October 15, 2014 (GP); photos updated and citations added by Graduate Assistant Eileen Gavin, April 9, 2025.