Field Hockey at UNI, 1901-1982

Introduction

People have played games very much like field hockey for thousands of years. In ancient Egypt and Greece, teams used a curved stick, club, or horn to move a ball against a goal defended by an opponent. The sport began to take on a more modern form in England in the middle of the nineteenth century. The popularity of the better-defined game grew rapidly. It spread to the United States by the 1890s. It was an Olympic sport in 1908. An unusual aspect of the game is that, even in the late nineteenth century, field hockey was considered a sport in which it was proper for women to participate. Indeed, when the sport came to the United States, women's colleges in the East were among the first to adopt it.

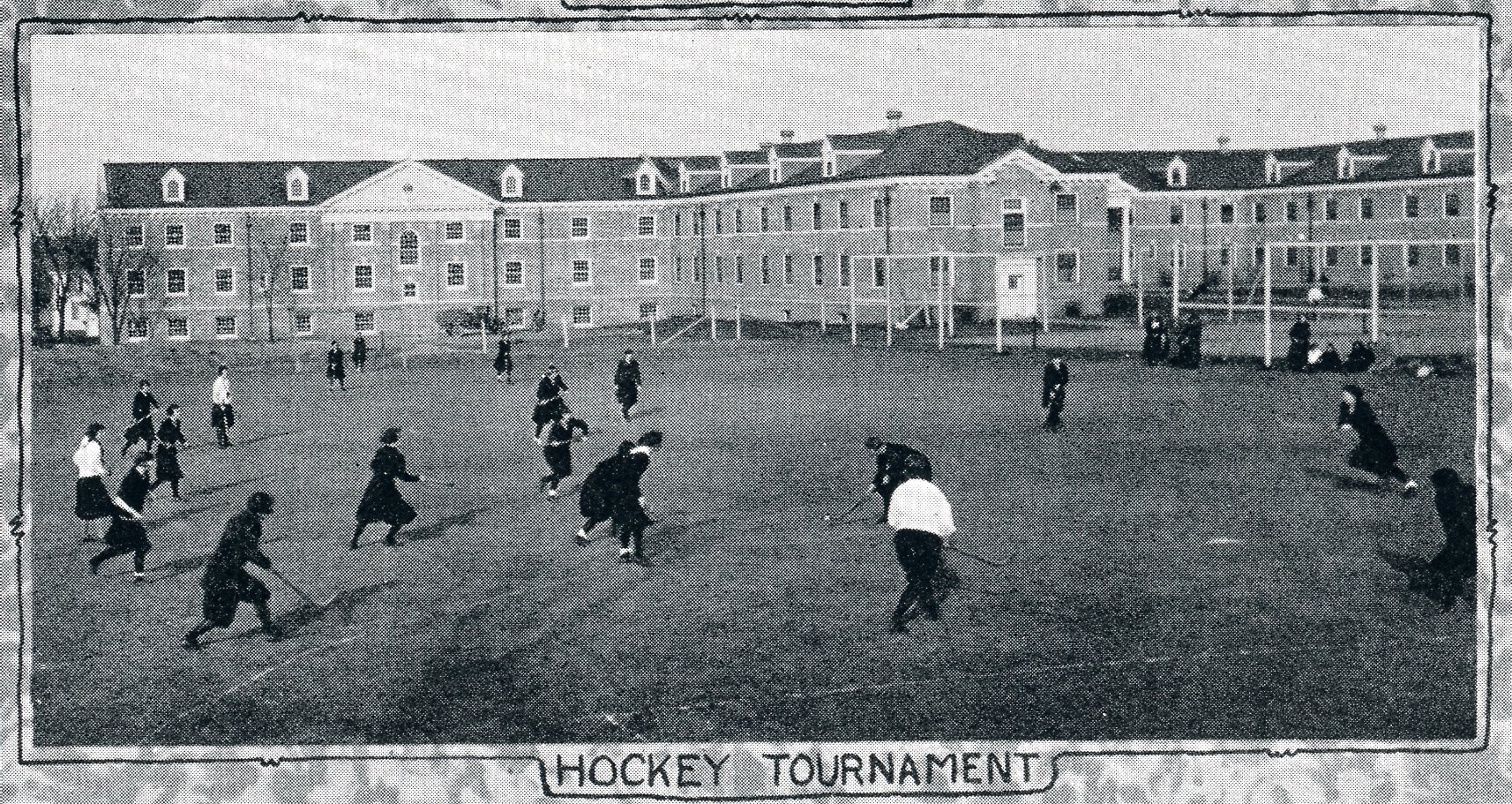

The Iowa State Normal School, now the University of Northern Iowa, began to bring greater organization to its physical activities program when it hired George Baird Affleck as the school's Physical Director in 1901. Professor Affleck had a degree from the University of Manitoba and then studied at the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts. The YMCA school had a well-deserved reputation for training young men in what would later be called physical education. In his work at the Normal School, Professor Affleck supervised both the curricular and extracurricular aspects of physical education. He taught classes and coached the athletic teams.

In September 1901, shortly after his arrival on campus, Professor Affleck announced that he would introduce "lawn hockey" to the Normal School. He had probably learned about the sport when he was studying at the YMCA Training School in Massachusetts. The sport was new for most Normal School students. In his announcement, for example, Professor Affleck apparently felt the need to explain "It is played with balls similar to cricket balls." Professor Affleck asked that "All men desiring to learn about this game, should meet him for a few minutes in the armory . . . ."

Field hockey caught on quickly at the Normal School. Just a week after Professor Affleck's call for participants, the student newspaper, the Normal Eyte, noted that "Hockey seems to be the game that attracts all not playing football this fall." In the 1902-1903 school year, two men's field hockey teams at the Normal School played a series of matches against each other. A long article in January 31, 1903, issue of the Normal Eyte praised the value of the game:

- it promoted physical and mental wellbeing;

- the cost of equipment was reasonable;

- the relatively large team size meant that many players could participate.

The article also advanced the notion that the sport need not be limited to men.

[Field hockey} did not become general in this country till about 1900 when several of the colleges for women used it as the general type of athletics . . . From this beginning, the game has spread until it bids fair to become the favorite among both sexes in high schools and colleges.

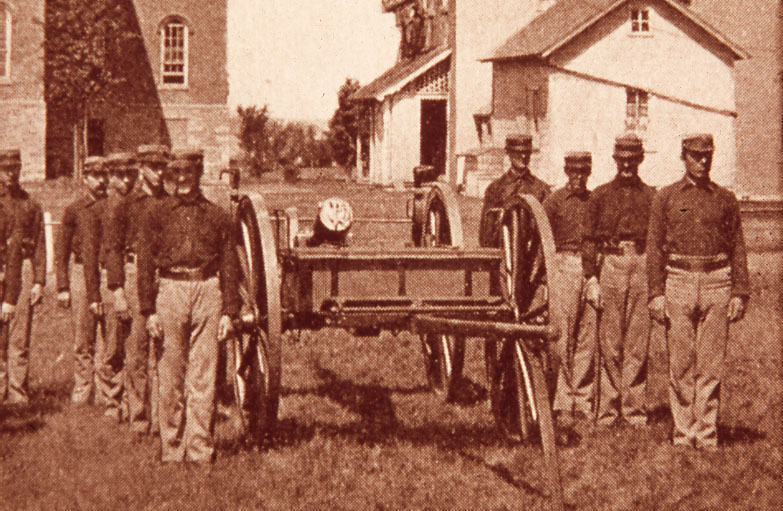

The year 1903 brought a major change in men's physical education at the Normal School. In that year, Major Jerauld A. Olmsted, who had been head of the school's military training program, was transferred away from Cedar Falls to duties with the Iowa National Guard. Without professional military leadership on campus, the Normal School ended its military training program. However, since military training had served as a form of physical education for men, the school needed to find a replacement for that part of its curricular and extracurricular programs.

Beginning with the 1903 fall term, instead of participating in one hour of military drill three times a week, the men were required to participate in some sort of physical activity four times a week for forty-five minutes. They could choose among basketball, tennis, football, field hockey, track, cross country, and golf. Basketball and tennis were the men's most popular choices, but football, track, and field hockey were close behind. The other two sports attracted few students. The student newspaper speculated that compulsory athletics for men would help to build stronger intercollegiate teams at the Normal School.

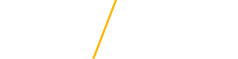

The men who chose field hockey as their activity divided into teams and played each other in the fall of 1903. They played on the football field that stood about where the Rod Library is now located. Also that fall, women students began to play field hockey in their physical education classes. At least fifty women participated in several field hockey matches that fall.

Both the men's and the women's games continued to be popular. In December 1905, Professor Affleck wrote an article on the sport for the Normal Eyte. He offered some history of the game and noted that, in addition to the Normal School women, Cornell College and Coe College women also played field hockey. He outlined some of the advantages of the game and went so far as to say that, in some circumstances, it might be a better game than football. He noted in particular that "The probability of accidents to the persons of the players is reduced to the minimum." As background to this statement, just two months before Professor Affleck's article appeared, President Theodore Roosevelt had threatened to ban intercollegiate football, because it had become too rough. In citing the relative safety of field hockey, Professor Affleck was likely responding to the broad national concern over the dangers of football. President Homer Seerley and the Normal School Board of Trustees were not satisfied with progress on the reform of football rules, so the school did not field a football team for the 1906 and 1907 seasons. A number of men were reported to have left school as a result of this decision. During that time, field hockey may well have attracted some of the interest that would normally have been devoted to football.

Normal School football was authorized again for the 1908 season, but the team was late in organizing. They did not play their first game until October 17 and then managed to play only four games in the entire season. So, at least initially, interest in field hockey remained strong. The sport continued to be part of the curricular physical education program for both men and women. And, in the extracurricular area, two teams of Normal School men played a series of exhibition matches against each other in the fall of 1908. The men looked for matches against other colleges, but apparently did not find any opportunities for intercollegiate competition.

The year 1908 may have been the high point for men's field hockey at the Normal School. Thereafter there are just a few scattered references to men playing field hockey at the school. Football (under reformed rules), basketball, baseball, and track became the mainstays for men. However, women's field hockey had quickly become a fixture in the women's physical education curriculum and would remain there for many years to come.

In 1923, the Women's Athletic Association was formed. This association had both active and honorary aspects. First, it helped to organize women's athletics activities. But, second, it also honored women students who participated in what would become intramural athletics. In the days before women's intercollegiate competition, this in-house activity was the highest level of competition to which most Teachers College women could aspire. The purposes of the association were: "...to foster interest and participation in athletics, to increase physical efficiency, and to develop a higher degree of sportsmanship and school and class spirit among the women students of the college."

The Women's Athletic Association organized tournaments with competition among the freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior classes in field hockey and other sports. In 1922, Constance Appleby, of Bryn Mawr College, had put together a set of rules designed specifically for women's participation in the sport. By 1923, the Teachers College was a member of the American Hockey Association, which subscribed to these rules. As a benefit of membership, the school obtained the services of a Scotch and English field hockey champion, Miss Emery, to demonstrate the latest strokes and skills of the game. Large groups of women turned out to learn from Miss Emery, who was on campus for a week in October 1924. Just a few weeks later, a field hockey tournament was a major feature of Class Day competition at the college. In that tournament, the senior women defeated the junior women, 4-2.

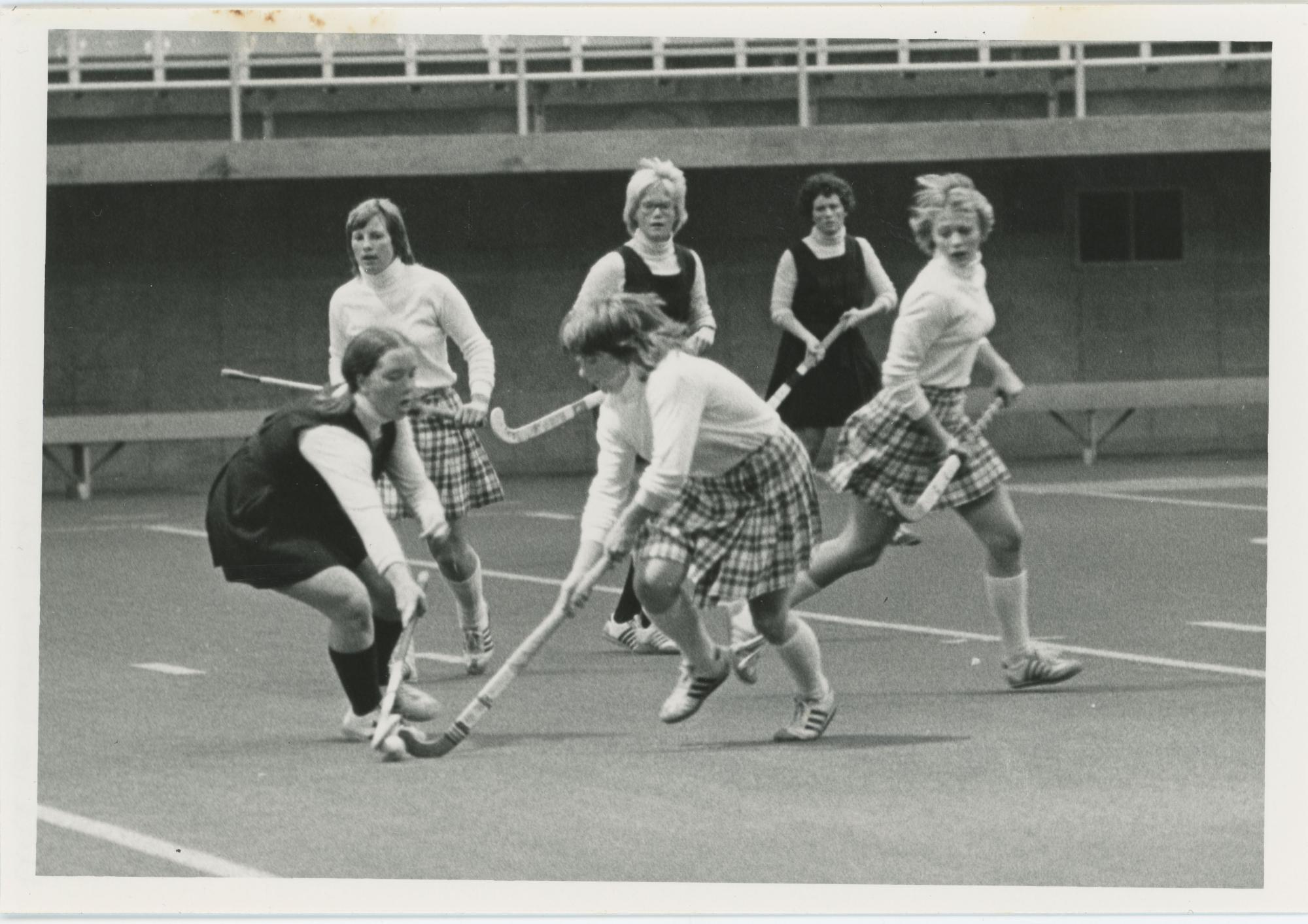

The Sport Flourishes on Campus

Women's field hockey became a regular part of sports reporting in the student newspaper during the rest of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. The school yearbook, the Old Gold, usually featured photos of women participating in the sport. Field hockey was primarily a fall sport, with most activity concluding in a tournament shortly before Thanksgiving. Outdoor sports during the late fall occasionally ran into mud, snow, and cold wind, but the Women's Athletic Association and the women's physical education faculty saw to it that play continued and good spirits prevailed even through difficult conditions.

When women chose their curricular physical activity in the fall of 1929, field hockey was the favorite, with soccer, tennis, swimming, and archery following. In addition, during the 1929-1930 school year, over five hundred women participated in intramural sports. On November 1, 1930, faculty members from the Department of Physical Education for Women--Helen Manahan, Marjorie Adams, Harriette Egan, Delia Kolling, and Dorothy Humiston--went to Iowa City for a hockey play day organized by the Iowa City hockey club. Student Wilhelmine Haley accompanied them for what was likely more of a demonstration or clinic than strict competition.

The widespread interest in field hockey on the Teachers College campus at that time is hard to overestimate. In the early 1930s, even the Delphian Literary Society fielded a team that swept intramural competition. In 1932, and probably extending back to the early 1920s, a hockey match between physical education alumni and current physical education students was part of Homecoming activities. This match became a tradition that was maintained for many years. In the fall of 1933, college officials planned to lay out a new hockey field as part of the landscaping and grading associated with the construction of the new Commons. The field would be west of the Commons. With the construction of Lawther Hall just a few years later, it is unclear whether or not that field was developed. Most hockey games probably took place on the field just west of what was then the Women's Gymnasium, now the Innovative Teaching and Technology Center.

Dorothy Michel had been a strong proponent and teacher of field hockey classes at the Teachers College since joining the faculty in 1927. In the fall of 1936, she and eight students from her third year hockey technique class went to Iowa City to watch a touring Welsh team compete against several Iowa City clubs. Professor Michel said that it was a privilege to be invited to see an international team play. In 1938, she and Professor Thelma Short accompanied a group of students to Iowa City.

That visit was split between two activities. In the morning the students played against other Iowa college women. And in the afternoon they all watched a match between the Chicago Field Hockey Association and the Iowa Field Hockey Association.

Later that year, in an article entitled "Is Woman the Weaker Sex?", student newspaper writer Betty Lou Wood made it clear that women's field hockey was a tough sport. She noted that even when women wore shin protectors, contact with the hardwood clubs could leave lasting impressions. She said that a field one hundred yards long and sixty yards wide might be pleasant to look at, but that running up and down that field at full speed required strength and endurance. Occasional reports in the newspaper about hockey-related injuries supported Betty Lou Wood's claim.

Interest in field hockey as a part of the women's physical education curriculum and as a recreational activity continued during and after World War II. In 1944, the Women's Athletic Association changed its name to the Women's Recreation Association, probably to reflect its purpose more accurately. In some years, in order to introduce the game to new students, the association staged an exhibition match featuring experienced players. Shin guards and sticks were available to any woman who wished to play.

After the war, the Teachers College sometimes looked outside of the school for competition and education in field hockey. This may have happened for several reasons. First, it may have been the next, logical thing to do. Second, it may have been an attempt to begin to parallel longstanding practices in men's athletics. Or, third, it may simply have been that transportation became more convenient and affordable.

In the fall of 1948, a team from Iowa State University came to campus and beat a Teachers College team, 2-0. On November 5, 1949, two Teachers College teams went to Iowa City for the Midwest Hockey Umpiring Tournament. There were teams from about twenty colleges at the tournament, which fostered both the curricular and extracurricular nature of the sport at that time. Teams competed against each other, and students had the opportunity to study and learn teaching techniques. Just a couple of weeks later, a Teachers College team traveled to Ames to play an Iowa State team. In a "rough and tough" game, the teams battled to a 1-1 tie. In a rematch in 1950, the Teachers College defeated Iowa State, 3-0. In the fall of 1951, Teachers College teams were scheduled to play against teams from both Ames and Iowa City. In each of these cases, the Teachers College teams seem to have been intramural all-stars. Bad weather canceled the trip to Ames, but both the Iowa State team and the Teachers College team then planned to go to Iowa City where they would compete against teams from several other colleges. The results of that competition have not survived.

By the middle 1950s, news in the College Eye about field hockey was limited primarily to announcements about the formation of intramural teams and the traditional annual match between current students and alumnae at Homecoming. There were, however, occasional special events. In 1956 a Teachers College team defeated a Grinnell College team twice. In 1963, the college brought teams from Argentina and Switzerland to campus to play an exhibition match. These two teams were part of a group of amateur international teams touring the United States and playing exhibition matches. A large number of students enjoyed meeting the teams and trying a little classroom Spanish and German with team members before watching the match. The Argentineans won, 1-0.

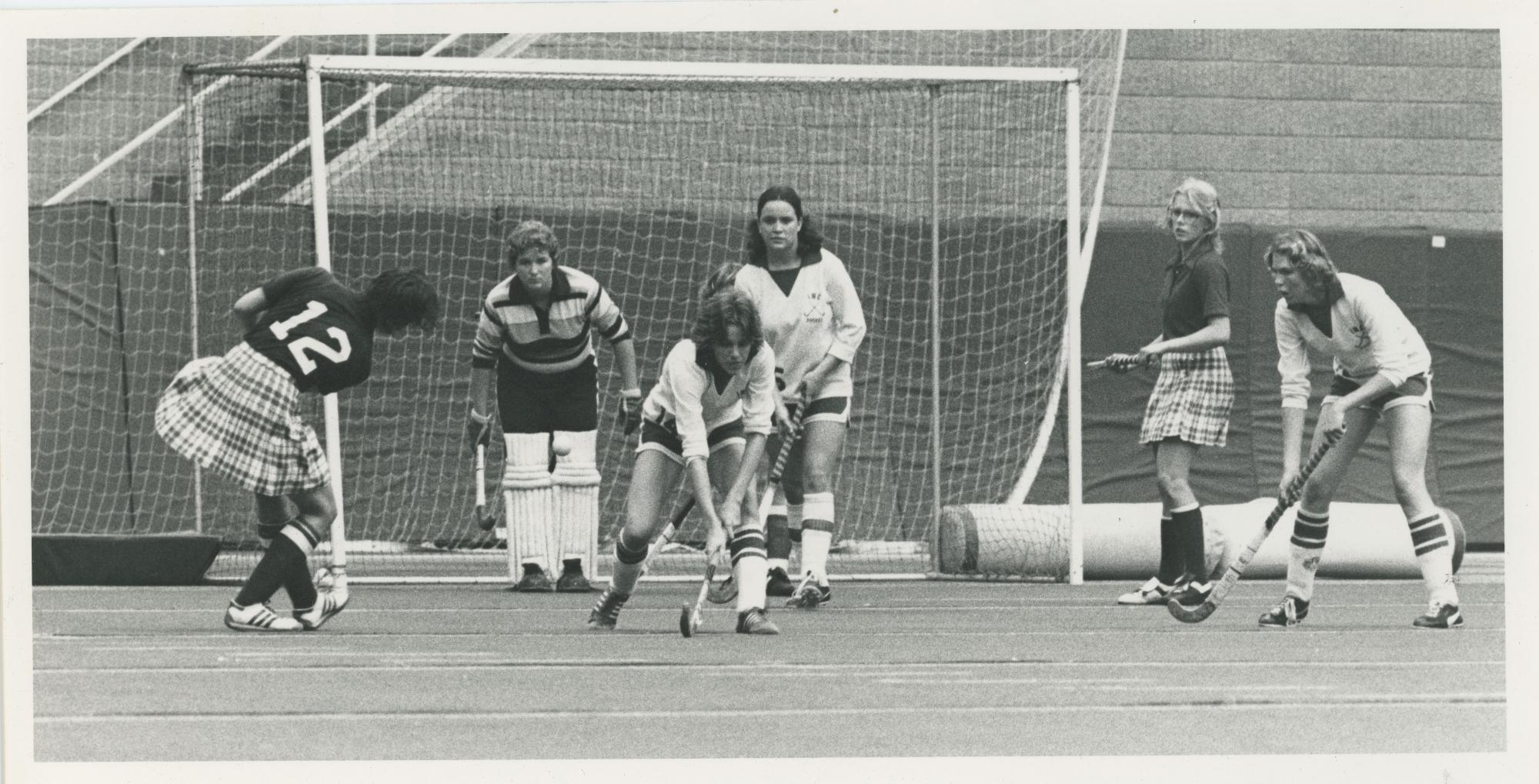

The Intercollegiate Team

The 1968-1969 school year brought remarkable change for University of Northern Iowa women who were interested in participating in sports. In that year, several women's intercollegiate teams were organized. In the fall of 1968, the women's basketball team was formed and played its first game on December 7, 1968. The women's tennis team began formation in April 1969 but may not have played its first match until the next school year. And, it seems as if an intercollegiate field hockey team formed sometime during the 1968-1969 school year, but it is unclear if they played any matches that year.

Note: There are several things that a reader should consider before going on to the account of the intercollegiate field hockey team below. First, information about the team is incomplete and needs considerably more investigation. The student newspaper and the UNI sports information office provided good coverage for some years. Indeed, a few Northern Iowan articles showed a remarkably good knowledge of the game. In some years the newspaper provided practically game-by-game coverage for the entire season. But coverage for other years is spotty, occasionally contradictory, and even patronizing. Consequently, this account can only be regarded as a quick survey of UNI intercollegiate field hockey history.

Second, for at least the first few seasons of the intercollegiate team, the organization and the competitive rules were quite different from what one might expect for university-level competition. To some extent in those early years, intercollegiate field hockey seemed to retain many of the aspects of its heritage as a club sport with a strong educational component. The team did play against other college and university teams. But they also played against local field hockey clubs, such as the Northeast Iowa Field Hockey Club. These clubs were amateur associations composed of women from a variety of backgrounds: former collegiate players, physical education teachers, and anyone else who wished to play the game. But the team honored its curricular and educational heritage, too, by competing in special matches or tournaments that were arranged either to teach field hockey skills or to train field hockey umpires. Also, season championships were different. The early seasons of the field hockey team culminated in a state championship tournament rather than a conference championship. Teams gathered for the state tournament and the winner would be the state champion. Following the state tournament, an all-star team (or sometimes two all-star teams), selected from all of the teams at the tournament, would move on to the regional competition. Many UNI players were chosen for these all-star teams. Following the regional competition, another all-star team would be selected from regional competitors to advance to the national competition. UNI players occasionally advanced to this level. Over the years, the older club-style rules faded and the organization of the season came to look more like modern NCAA competition. But it was not until its last year of intercollegiate field hockey competition that UNI participated in a true conference championship tournament.

The field hockey team did play in the fall of 1969 under coach Elinor Crawford, a member of the faculty of the Department of Physical Education for Women. The team played about seven games, and they won the state championship in a tournament that featured eight other teams. Coach Crawford was pleased with the performance of her relatively inexperienced team. Captains that year were Judy Martin, Kathy Wallis, and Adele Todey.

The 1970 season, in which the team posted a 2-4 record, was less successful. But they bounced back with a strong 1971 season. They finished the regular season with a 5-0-1 record and then won the championship at the state tournament with three more wins. Coach Crawford said: "You can give credit to the scorers, but it is always a team victory. We've had a good year. These girls are great."

Despite losing strong players from the 1971 team, including the entire forward line, the 1972 team performed well. They finished undefeated, with a 5-0-3 record. Ten UNI players were named to the state first and second all-Iowa teams, which competed and did well at the Midwest Tournament.

In 1973, Wanda Green, a faculty member in the Department of Physical Education for Women, became coach of the field hockey team. Coach Green was an excellent field hockey player herself. She had coached hockey clubs before, but this was her first intercollegiate coaching experience. The 1973 team posted a 6-3-1 record, with two wins at the state tournament. Eight UNI women were selected at the tournament to play on the Iowa team at the Midwest regional tournament: Lori Kluber, Teresa Allen, Diane Braun, Mary Taylor, Donna Troyna, Betty Hala, Jenny Alberti, and Laurie Hanson. After Midwest Regional play, Diane Braun moved on to the next level of competition as a goalie on a South Regional team. Diane Braun's selection was remarkable. While she was an excellent all-around athlete, she was relatively inexperienced in field hockey.

1974 was another excellent season. The team went undefeated with a 10-0-1 record. Six members of the team were selected to the all-Iowa team that advanced to regional competition. After that competition, Diane Braun again advanced to national level play. In addition, Diane Braun, Lori Kluber, Donna Troyna, and Mary Taylor were selected to play in an exhibition match against the Welsh Touring Team.

In 1975 Coach Green implemented a more offense-oriented style of play, with four strikers, two links, three thrusters, one sweeper, and one goalie. The team defeated Iowa in the year's opening match, but then lost to strong teams from Luther College and the University of Wisconsin at LaCrosse. They came back with a win and a tie in the next two games. They won the next three games and moved on to the Midwest Umpiring Conference competition, where they won one game and lost two against strong opponents. UNI then won the Iowa Field Hockey Selection Tournament and placed ten players on the two Iowa College teams that advanced to the Midwest Field Hockey Tournament. Following that tournament, seven UNI players moved on to the national tournament.

The 1976 team repeated the excellent performance of the 1975 team. They continued to use the 4-2-3-1-1 formation. In their opening game, played in the UNI-Dome, the UNI team defeated the University of Iowa, 4-0. The team put together a 7-2-2 record before advancing to the state selection tournament, where ten UNI players were chosen to participate in the Midwest regional tournament.

1977 was a tough year for the field hockey team. Nine seniors had graduated, and the team faced a schedule of tough opponents. At least at the beginning of the season, Coach Green had difficulty in fielding a full team. Their record was 0-4-1 before they won their first game, a 1-0 victory over Luther College. They then lost all four games at the Lake Forest Invitational Tournament against strong teams. But the Panthers learned and grew over the year. At the state tournament, the team compiled a 3-2 record and finished third. The overall season record was 4-11-3, but they finished well.

Unfortunately, the 1978 field hockey team could not build on its strong 1977 finish. In April 1978, a note appeared in the student newspaper announcing an: "Organizational meeting open for any interested woman. No previous experience necessary."

Perhaps the university had been unable to attract enough women to participate in the sport. Perhaps promising high school and college women athletes were more attracted to sports such as basketball, volleyball, and softball. In any case, the 1978 season did not turn out well. Seven players returned to the team from the previous year, but the rest of the players had little or no field hockey experience. The team lost its first six games before winning two games at the Lake Forest Invitational Tournament. Unfortunately, those two wins would be the only wins in the tough 1978 season. In most of their losses, the Panthers did not score.

The 1979 season was a bit better than the 1978 season. The team lost its first eight games before tying Luther College. It then won its first game by defeating Grinnell College in a contest concluded by penalty shots. UNI then defeated a club team from Nebraska. After playing well in sub-regionals, the team advanced to regional competition. The team lost both of its games there and finished with a 5-12-2 overall season record.

Coach Wanda Green was on leave for the 1980-1981 school year for graduate study, so Lois M. Hartman took over the coaching duties. Coach Hartman was a physical education teacher at Grundy Center High School.

She was an experienced field hockey player, who had played at UNI for three years. She believed that the team had a strong returning core of players who could build upon their experience and compete well. Coach Hartman was correct. The team compiled an 8-3 record before advancing to divisional play. UNI then hosted the regional tournament, where the Panthers ended their season with two losses. Their overall season record was 9-9.

In 1980, the field hockey team had begun to face serious challenges off the field. In the spring of 1980, two field hockey team members, Kimberly Gibbs and LeAnn Erickson, had filed a grievance against the university under Title IX of the Federal Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX essentially resulted in requiring colleges and universities to provide appropriate levels of funding to women's athletics in terms of coaching, facilities, travel, scholarships, and other areas. The university's Title IX compliance officer, Harold Burris, decided that the grievance had sufficient validity to move forward. In the spring of 1981, the Athletic Policy Advisory Council, citing lack of funds to comply with the grievance, considered the elimination of field hockey and the men's and women's gymnastics programs. It also suggested that the university take a hard look at eliminating baseball. Ultimately, the Council recommended eliminating the two gymnastics programs, but, at least for a time, to retain field hockey "contingent upon the ability of the institution to make staff reassignments to the School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation." Baseball would be spared. The President's Cabinet approved these recommendations.

So, with Coach Wanda Green back, the field hockey team would have a 1981 season. The school year opened with an announcement in the student newspaper asking interested players to contact Coach Green. This suggests that the team was again having difficulty in recruiting players. The season did not go well. After losing their first six games, the Panthers won three games. But that would be the high point of the season. In the rest of the season, they lost all but one game, including four games at the regional level. Their season record was 4-16. Coach Green commented that her team played well on many occasions, but, overall, the season was disappointing.

1982 was the last season for intercollegiate field hockey at UNI. In September 1982, Coach Green offered an explanation for the university's decision to eliminate the sport. She stated that field hockey was not widely played in Iowa high schools, so UNI team members frequently had little experience when they joined the team. UNI did not have sufficient funds to recruit in areas beyond Iowa where the game was popular. It had also become difficult to find officials for field hockey competition. Still, Coach Green hoped that the team could put out a good effort in its final season. Goalie Vicki Judkins echoed her thoughts. She knew about field hockey only because her high school physical education teacher had played for UNI. Vicki Judkins was sorry about the elimination of the team, but understood that the university did not have funds to continue the program at UNI. She thought that the team could build on its 1981 experience and perform well.

Unfortunately, the season was difficult. On at least one occasion, the team was able to put only ten players on the field, instead of the requisite eleven. The Panther field hockey team played its last home match on October 20, 1982, a hard-fought 2-1 loss to Luther College. The team did have two good wins over Grinnell College, but it concluded its season with a string of losses at the Bemidji State Invitational Tournament and the Gateway Conference Championship. Sheryl Sigmund scored the last goal for the Panthers. With the end of the UNI field hockey team already determined, it was ironic that the Panthers' first appearance in an intercollegiate conference championship tournament would also be the team's last appearance. Coach Green commented that it had been difficult to prepare for the conference championship because she and her team knew that the level of competition there would be more than her team could match.

Summary

Field hockey was an extraordinarily popular participatory sport at the University of Northern Iowa for many years. Thanks to innovative Physical Director George Affleck, the sport arrived on campus early, not long after the turn of the nineteenth century. Both men and women participated initially. However, after football returned in 1908 from its two-season banishment from campus, men's interest in playing field hockey faded and then disappeared. Under the strong leadership of faculty associated with women's physical education on campus, field hockey developed into an important part of both the curriculum and the recreational program for women students and even became one of UNI's first women's intercollegiate athletic programs.

The women's intercollegiate field hockey program thrived in its first few seasons. UNI fielded strong teams that won state championships and consistently advanced players to regional and even national competition. The team and its coaches were able to accomplish this while retaining the heritage of older club-style competitive rules and viewing the game as part of an educational program. However, despite a good showing in the 1980 season, most of the team's later seasons were less successful, at least in terms of won-lost records. This probably occurred for several reasons. First, Iowa high schools did not feed experienced field hockey players into the university's program. Because they had insufficient funds to recruit in areas where field hockey was more popular, coaches needed to spend a great deal of time simply teaching the game to inexperienced players. Second, by the late 1970s, women's intercollegiate athletics administrations were bringing their programs more strictly into accord with national standards. If programs wished to compete nationally, then they had to comply with stricter national regulations. For example, programs needed to compete against teams within their own divisional classification. This meant that competition would be tougher. It also meant that UNI would need to travel more to meet that competition. Unfortunately, there were insufficient funds for that. Title IX rules, requiring greater equitability between men's and women's teams, made the funding situation critical. The field hockey program was among the sports that were eliminated as a consequence. The intercollegiate program began at a time when interest in field hockey was beginning to fade and interest in other sports was rising. Had the program begun twenty years earlier, it might have had a better chance of succeeding.

Even though the UNI intercollegiate field hockey program ended in less than happy circumstances, the sport was certainly not a failure over its long history at the school. Men abandoned the game fairly early. But women used the extensive intramural program as an outlet during the long years when opportunities for women to participate in athletics were severely circumscribed. Untold numbers of women improved their physical conditioning by participating in the sport. Physical education students who took classes featuring field hockey learned techniques that they could generalize to the teaching of other sports. Women who played the game learned to work together as a team.

As noted above, this essay is only a broad historical outline of field hockey at the University of Northern Iowa. A definitive history remains to be written. Scholars need to take a closer look at the sport as an integral part of the physical education curriculum and the recreation program. Much more needs to be uncovered about the intercollegiate program, from basic facts about game results to a deeper analysis of the factors involved in eliminating the program. Future scholarship, however, is quite likely to reinforce the contention of this broad essay. Field hockey was a successful and valuable part of the curriculum and the recreation program, and, later, the intercollegiate athletics program at the University of Northern Iowa for over eighty years.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson; research by Student Assistant Julie Herrig and Library Assistant David Glime; scanning by Library Assistant David Glime; February-March 2011; Photos updated by Lydia L. Pakala June 2019. Updated by Matthew Bancroft-Smithe February, 2021; photos and citations updated by graduate assistant Eliza Mussmann May 5, 2023.