Lincoln, the Civil War, and UNI

Introduction

Abraham Lincoln never heard of the institution now known as the University of Northern Iowa. That institution, initially known as the Iowa State Normal School, did not open until eleven years after his death. But, once the school opened in 1876, the Normal School and then the Teachers College certainly heard plenty about Abraham Lincoln and about the Civil War, which occupied nearly all of his Presidency. The school owes its very existence to the effects of the Civil War. What is more, Lincoln and the Civil War were important parts of the intellectual, political, emotional, and even religious lives of the school's faculty, staff, and students for at least the first fifty years of the school's history.

The Lincoln Legacy, 1876-1909

As the Civil War approached, most Iowans sympathized with the Union point of view. They supported Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 Presidential election, and, after war broke out, over 75,000 Iowans ultimately joined the Union military forces. Some historians claim that Iowa, in proportion to its population, sent a greater number of men to the Civil War than did any other Union state. Whether or not that is true, many Iowans were killed in battle or died in camp and did not return home. That left many widows and orphans in very difficult circumstances. Influenced by dedicated and charitable Iowans such as Annie Turner Wittenmyer, the General Assembly decided that it would show its gratitude for the sacrifices of Iowa veterans by establishing orphans' homes in several locations around the state.

One of those locations was Cedar Falls, where citizens purchased forty acres of land and also collected a substantial amount of money to construct a new building that would serve as an orphanage. Today, that forty acres comprises the older, eastern part of the University of Northern Iowa campus. But, in the 1860s, that area was open, rolling land.

The Orphans Home was an impressive structure standing alone on a hilltop southwest of Cedar Falls. It was a monument to the strong emotional attachment that Iowans had for their citizen-soldiers and the Union cause.

Hundreds of orphans lived in the home. But, over the course of the years, the orphans grew up and went out into the world on their own. As the number of orphans dwindled, the state decided to consolidate its orphans' homes operations into its Davenport location. Consequently, by the summer of 1876, the state would have a large, relatively new building standing vacant on the prairie. Wise men in the Iowa General Assembly, including Civil War veteran Edward G. Miller, suggested that the building would be a fine location for a new teacher training institution or normal school.

After considerable deliberation, the General Assembly passed legislation that established the Iowa State Normal School in Cedar Falls. On September 6, 1876, the first class of what would eventually become the University of Northern Iowa was held in the former Orphans' Home building. That building, later known as Central Hall, would survive as a classroom building until 1965, when it was destroyed by fire.

So, from its earliest days, the school had strong physical ties to a Civil War heritage. Its very campus was a legacy of that war. But intellectual and emotional ties were strong, too. During the first quarter century of the school's history, from 1876 until the beginning of the twentieth century, most Normal School students would have had close relatives who had seen service in the Civil War: their fathers, brothers, uncles, and cousins were probably still telling old stories about their war experiences. Some family members or friends back home might still walk with a limp from an old wound. Their mothers or grandmothers might talk about their work in the Women's Relief Corps during and after the war. And, at quiet times, they might unfold old, poignant letters received from someone who did not come home from the war. For those early students, the Civil War and the leadership of Abraham Lincoln in keeping the Union together were, if not first hand experiences, an important part of their intellectual and emotional make-up.

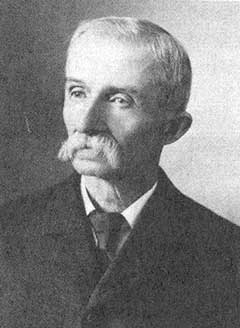

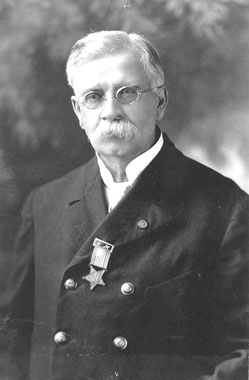

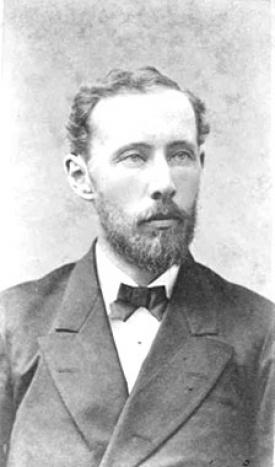

On campus, the faculty was composed almost entirely of men and women from the North. Indeed, at least five staff members were Civil War veterans. Professor Melvin Franklin Arey (22nd Maine Infantry), Professor William Wesley Gist (26th Ohio Infantry), Major William Dinwiddie (Iowa Volunteers), Professor Albert Loughridge (4th Iowa Cavalry), and Superintendent Alexander Martz (6th Pennsylvania). These men were active in the Grand Army of the Republic, an association of Civil War veterans and one of the most important political forces in the United States in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Professor Gist was elected Commander of the Iowa Department of the GAR in 1923. These men added gravity and a special patriotic overtone to events such as Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, and Lincoln's birthday. Some of these old veterans survived into the 1920s and could be relied upon to appear at these events, sometimes wearing military decorations or GAR ribbons that testified to their service.

Students reflected the reverence in which their faculty and families held Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War experience. Student essays and addresses regularly took Lincoln as their subject. In 1893, senior Annie Lees gave a Commencement address on Lincoln, in which she virtually deified him: "Lincoln was the sacrifice for national sin and thus was the bringer-in of national redemption." Just a year later another student, Frances Katherine Laird, wrote an essay on Lincoln in the student newspaper that paid special attention to his leadership in the Civil War. She closed her essay by quoting from the Gettysburg Address and asking for a blessing: "May God make us worthy of the memory of Abraham Lincoln." Just a year later two prominent public speakers, Colonel Ingersoll and Henry Watterson, spoke on Lincoln in the local community. Both men referred to Lincoln as a "divine man", sent from God. In 1896, student Steven Stockwell concluded his award-winning oration on Lincoln with the words: "Then to Lincoln--Statesman, Patriot, Emancipator, Martyr of Martyrs, Savior of his Country, forever hail!"

In the spring of 1897, the Normal School received plaster casts of portions of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on the Capitol grounds in Des Moines. These two casts, "Return Home After the War" and "The Storming of Ft. Donaldson", were mounted on corridor walls. They may still be seen today in the hallway outside the auditorium in Lang Hall.

In addition, one of the featured campus lecturers for 1897 was Charles Henry Fowler, a well-known lecturer and Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. In his presentation, Bishop Fowler put Lincoln into the same category of men as Moses and St. Paul. By the late nineteenth century, Abraham Lincoln had clearly assumed god-like status on the Normal School campus.

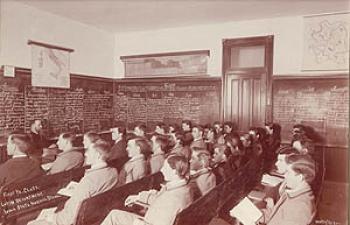

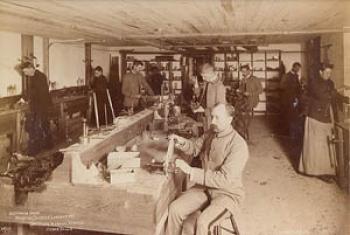

In case students needed any additional reminders of the Civil War, they had only to look around their classrooms. In the early 1890s, students had petitioned the school's administration to offer military training. The administration put together a curriculum and training program, initially under the direction of Professor Albert Loughridge, a Civil War veteran, as a temporary assignment. Later it became the regular assignment of Civil War veteran Major William Dinwiddie. All men were required to participate in the Student Battalion. Completion of the program could lead to a commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army. The men wore their uniforms, still strongly resembling those of the Civil War era, to class on drill days.

Reverence for Lincoln continued into the twentieth century. During the first decade, campus literary societies and visiting lecturers presented Lincoln-related programs on a regular basis, often in conjunction with the commemoration of Lincoln's birthday, February 12. Activities heightened as 1909, the centennial of Lincoln's birth, approached. On February 12, 1909, classes were dismissed for half of the day. The local Grand Army of the Republic chapter and the Women's Relief Corps attended the campus commemoration at which Professor Gist, a Civil War veteran, delivered an address. At the program, the Class of 1909 presented its class gift to the school: a bronze slab on which was inscribed the Gettysburg Address.

There was another good Lincoln program on February 12, 1913; again Professor Gist presided. Professor Wright gave the major address in which he noted that Lincoln's birthplace was humble and lowly, "like the Saviour".

Changing Attitudes, 1910-2009

But attitudes toward Lincoln had begun to undergo a bit of a change at about this time. In an October 1913 article in the student newspaper, an editorial writer noted that, back in February, when President Seerley announced in chapel that classes would be dismissed so that students could attend the fine Lincoln program, many students had applauded wildly and fled campus. In a daring College Eye editorial in 1916, entitled "What Would Lincoln Say?", a writer seriously questioned the value of referring to the great figures of history whenever a difficult question arose. The writer said, "We all respect the men who are esteemed demigods by a great many of our citizens . . . But to spend our time in speculating on their probable action under a new set of circumstances and in the presence of new, and by them undreamed of, difficulties is the height of folly." The writer concludes, "Let Washington, and Lincolln, and Grant, and Ezekiel, rest. They have done their work." That sentiment represented a shocking shift in thought.

However, that editorial was not a complete and absolute turning point. Commemorations of Lincoln's birth continued after World War I. The 1919 celebration, with the Armistice of World War I just a couple of months in the past, was especially memorable for its patriotic presentation. Professors Gist and Arey participated. But, as personal, first hand memories faded, it is likely that Lincoln and the Civil War were becoming subjects to be studied in books. Civil War veterans were dying or becoming increasingly infirm. Alexander Martz, who had been severely wounded at South Mountain, had died in 1901. William Dinwiddie also died in 1901, and was buried with full military honors from the school chapel. William Wesley Gist died in 1923, shortly after being installed as Commander of the Iowa Department of the Grand Army of the Republic. The last campus Civil War veteran, Melvin Franklin Arey, died in 1931.

In 1926, the college accepted a portrait of Annie Turner Wittenmyer, who had led the effort to establish homes for orphans of Civil War soldiers and sailors in the 1860s. Her work, noted above, led to the construction of what eventually became the first building of the Iowa State Normal School. The whereabouts of that portrait are not now clear, but the school honored Mrs. Wittenmyer again in 1996 by erecting a sculpture in her honor on the east side of Lang Hall.

Through the 1920s and even into the 1930s, there were fairly regular, low-key commemorations of Lincoln's birthday offered by literary societies or in chapel. In 1925 the college even showed a movie about Lincoln: benefits from the presentation went toward sending men to the Young Men's Christian Association camp at Lake Geneva. In 1928 the student newspaper offered a review of Carl Sandburg's Abraham Lincoln, the Prairie Years. The review implied that this book would reawaken interest in Lincoln among students, who were bored by hearing the same old tired schoolroom stories about him.

By the mid-1930s, Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War seem to disappear just about completely from the campus, at least in so far as public commemorations are concerned. Birthday commemorations seemed to be relegated to grade schools. A few flickers of interest have appeared in recent years. In 1989, Professor Donald Whitnah, of the Department of History, remembered Washington and Lincoln in association with the bicentennial of the American Presidency. In 2001 the Northern Iowan featured a story on local descendants of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who was convicted of conspiring in the assassination of President Lincoln. In 2005, William Koch, of the English Department, gave a presentation of "Walt Whitman Live!" in association with the 140th anniversary of Lincoln's assassination.

In 2008, as the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth approached, Professors Wallace Hettle, Michael Blackwell, and John Baskerville presented a panel discussion: "Friends or Foes: the Relationship between Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln". And in 2009, in honor of the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth, the Center for Multicultural Education presented a series of programs and presentations related to Abraham Lincoln.

Summary

For the first fifty years of the history of the University of Northern Iowa, the most revered figure in American public life was Abraham Lincoln. Students and faculty of those years believed that Lincoln personified the best qualities of an American. He had risen from humble origins, studied and worked hard to improve himself, lived an ethical life, risen to great power, and then led the country through its greatest trial. His life was a continuing object lesson kept alive by personal memory, civic celebration, and school life. When personal memory of the Civil War era began to fade, and Lincoln became more of a history lesson than a life lesson, special commemorations of his exemplary life just about disappeared from campus. This might also have been due to the emergence of the United States as a world power. Americans began to take a broader view of history that extended beyond their own shores. Modern historical analysis has taken criticism of Lincoln to a point which earlier generations would have considered both unfair and unwarranted. However, even in today's frequently destructive historical analysis of many American institutions, Abraham Lincoln remains near the top of just about any historian's or political scientist's list of great Presidents. Wherever trends may take Abraham Lincoln's reputation, both he and the Civil War are fundamental to understanding the history of the establishment and early years of the University of Northern Iowa.

Compiled by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson; scanning by Library Assistant David Glime; photography by Library Associate Elaine Chen, January-February 2009; last updated, August 27, 2014 (GP).