Thanksgiving at UNI

Students, faculty, and staff have celebrated Thanksgiving since the earliest days of the University of Northern Iowa, not long after President Lincoln proclaimed the national holiday in 1863. While some aspects of the celebration have changed over the years, many traditions endure down to the present day.

The earliest report of a Thanksgiving celebration at UNI comes from the student newspaper, The Students' Offering, in 1878, just two years after the school's founding:

"At ten o'clock, the students assembled at Normal Hall, and listened to a very able and appropriate sermon . . . . At noon, all were happy in the prospect of dinner, and none were disappointed. Such a dinner! Col. Pattee and Mrs. Parsons, bless their generous souls, entirely surpassed themselves on this occasion, producing a dinner never to be forgotten by those who enjoyed it. Altogether, the day was a very pleasant one."

In those early days the school had just one main building, then known as Normal Hall and later known as Central Hall, that served as the home for all school functions. It held classrooms and meeting rooms. Most students and faculty lived and ate there as well. Colonel Pattee, the Steward, was in charge of the school's physical plant. Mrs. Parsons, the Matron, was in charge of the school's rooming and boarding facilities. The Thanksgiving holiday consisted of just a single day; regular recitations were held on the Friday following the holiday. Consequently, unless their homes were quite close to Cedar Falls, most students stayed on campus for the holiday. But a number of former students as well as friends of current students came to campus to celebrate.

In 1879 The Students' Offering glances at a Thanksgiving dinner menu that looks familiar to most of us today: "the customary turkey and all the auxiliaries of cranberry sauce, celery, coffee, mince pie, etc." Students spent Thanksgiving afternoon and evening with musical entertainment and refreshments.

At the Thanksgiving evening entertainment in 1883, the students presented Principal Gilchrist and his wife Hannah with a gold-headed cane and a clock.

By the early 1890s, the YMCA and YWCA were in charge of Thanksgiving morning religious services on campus. The student newspaper, the Normal Eyte, issued just before Thanksgiving in 1892 printed an especially poignant editorial on the holiday and its association with family life:

" . . . we, even in the whirl of school life, realize a longing for home and kindred . . . Giving the first importance of this day to a recognition of God's bounty, there is perhaps no other holiday which plays so conspicuous a part in the yearly family gathering as Thanksgiving Day."

These are pious, and, quite likely, heartfelt remarks. Yet in that same year the Normal Eyte reports that "an astonishingly large number of girls have brothers or cousins coming to see them on Thanksgiving." The playful implications of the editorial writer seem clear: the familial relationship of at least some of the "brothers" and "cousins" was suspect. Young women students might well have been anticipating visits from off-campus male admirers quite apart from their own families.

In 1895 students inaugurated a "Hare and Hound" race to be run on Thanksgiving Day. This seems to have been a kind of intramural cross country race run in the College Hill area between two teams of twelve students. The winner was the team with the better average time in running the course. 1895 also afforded the opportunity to show off the new Administration Building to campus visitors. This building, the third major college structure, was situated just east of where the Maucker Union now stands; it was demolished in 1984.

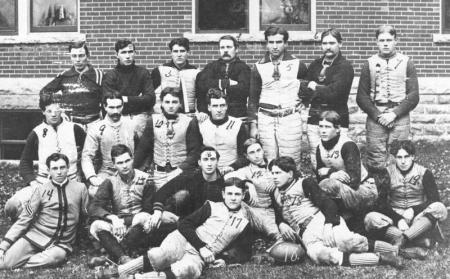

Football games have long been associated with Thanksgiving. With the rising interest in intercollegiate athletics in the 1890s, even small teachers colleges began to schedule football games on or around Thanksgiving. On Thanksgiving Day in 1897, the Normal School beat a team of local and visiting graduates, 8-0.

In 1900 the school newspaper began a tradition of presenting a list of things for which the editorial writer was grateful. Some of the items were humorous; some were serious. That particular writer was grateful for good food, good grades, a new building (now known as Lang Hall), and the opportunity to learn and to teach. Lists like this have frequently appeared in the student newspaper since that time.

At about this time, the school changed its academic calendar. The fall term concluded on the Tuesday or Wednesday before Thanksgiving, and the winter term began on the Monday or Tuesday after Thanksgiving. That gave most students sufficient time to go home for the holiday. Consequently, with most students at home and with no newspaper being published for several weeks, references to Thanksgiving are scarce for quite a number of years. In 1902 we learn that one group of students was so hungry for Thanksgiving treats that, when their train stopped in the Cedar Rapids station, they rushed to a food stand and bought a short order of turkey. They were shocked that their meal cost as much as fifty cents.

A writer in 1903 took a quite secular approach to the holiday and rejoiced that Normal Street (now College Street) had finally been paved with bricks. After over a quarter century of dodging and tripping in the mud, students could now walk, safe and dry, across the street on the east side of campus.

In 1913 the YWCA gave a Thanksgiving party for students who did remain on campus. In 1914, in a possible echo of the Hare and Hound competition of the 1890s, there was a cross country run for members of the athletic teams. The course ran east on 27th Street (now University Avenue) to Main Street, south two miles on Main Street (probably to what is now known as Viking Road), west to Hudson Road, and then back to campus.

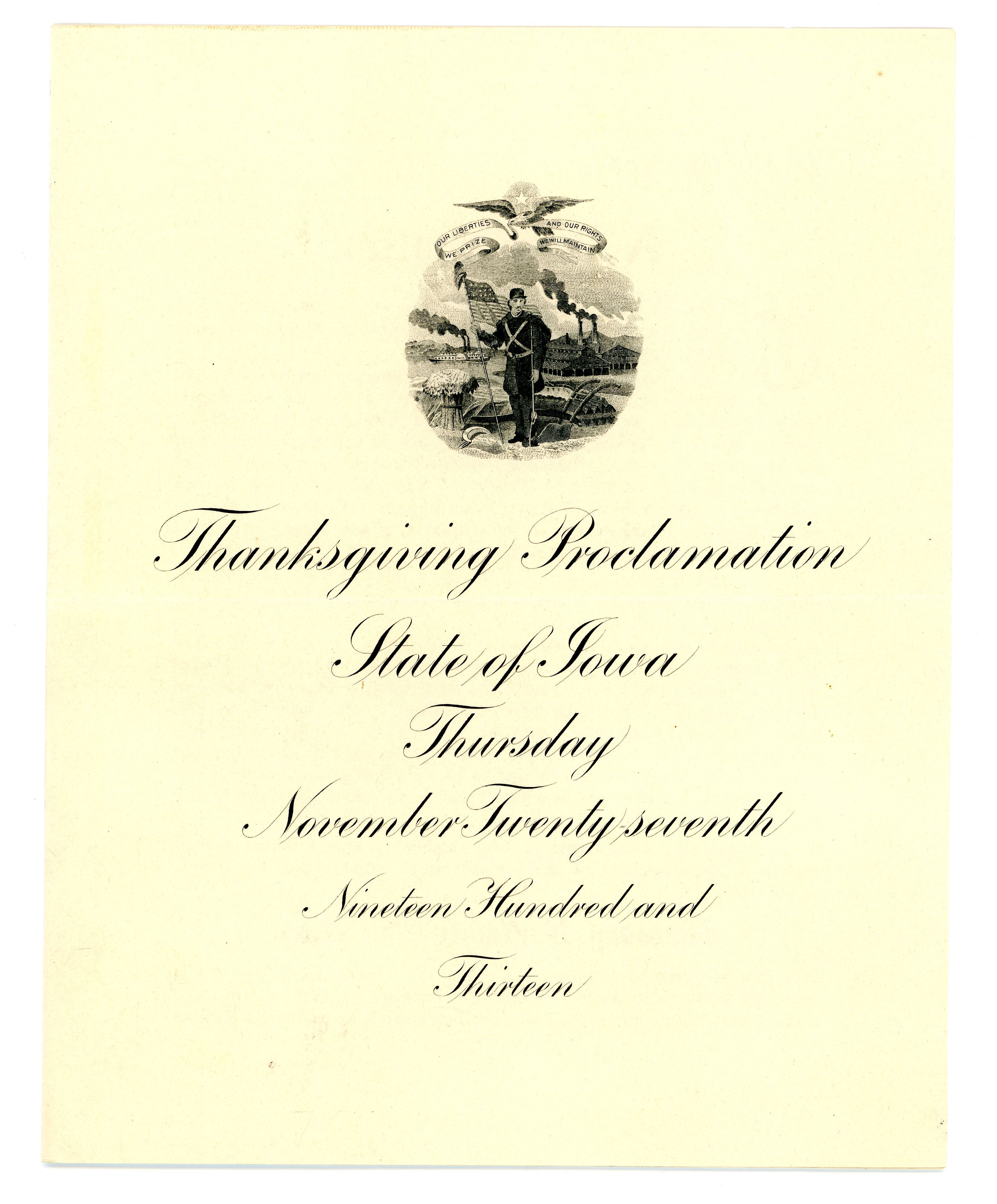

War and the threat of war sometimes add special meaning to certain holiday celebrations. In 1915, probably for the first time in nearly twenty years, a College Eye editorial writer took a serious look at the meaning of Thanksgiving. First, the writer shows nostalgia for home and family: he thinks that if students looked kindly at their families they could find that "maybe mother isn't such a commonplace woman", "maybe father is a pretty good "dad" in spite of his clay pipe", and that "maybe brother's and sister's teasing isn't the supreme apex of torture".

With the United States still over a year away from involvement in the fighting of World War I, the writer "thanks God that we are out of the cruel hell of war" and hopes that people will learn from the experience of war to accept brotherhood. Despite the seriousness of these sentiments, the school did play a football game on Thanksgiving Day and defeated Ellsworth, 24-0.

In 1917, with the United States at war, the newspaper printed President Wilson's Thanksgiving Day proclamation. The school did play a football game on Thanksgiving Day against Penn, but the week also featured a battalion parade by the young men training for military service on campus. The celebrations of 1918, so shortly after the Armistice, were ones of true Thanksgiving. The school held a special vespers service. The student newspaper offered a poetic religious tribute and then printed the words to S. H. M. Byers' Song of Iowa: "You ask which land I love the best, Iowa, 'tis Iowa". But there was time for fun, too. The Student Council hosted an all-campus party on the Friday night after Thanksgiving. Students and faculty played games and enjoyed refreshments.

The Student Council celebrated with a similar party in 1919, but, due to the coal shortage, the school closed on December 5 and did not re-open until after Christmas. The 1920s were marked with consistent complaints about an alteration in the academic calendar that scheduled classes on the Friday after Thanksgiving and ended the fall term on the Tuesday after Thanksgiving. This sentiment was epitomized in a bitter little free verse ode in the College Eye in 1926:

We Believe This

We know as well as you do that this is all Bunk,

This idea of everybody getting a vacation for Thanksgiving.

Because we all know we would rather have classes all day long than stay at home and eat turkey, luscious, juicy turkey covered with a golden brown crust,

Which turns sour in our mouths when we think of all the knowledge we could be assimilating!

No, sir, we don't believe in Thanksgiving vacation

So, once again, most students were forced to celebrate Thanksgiving on campus. At that time, many students lived in rooming houses on College Hill. The newspaper reports on one Thanksgiving celebration at the Ferguson Hall rooming house in 1920, where sixteen women and several guests gathered to enjoy a turkey dinner as well as treats sent from home. Tables were decorated with chrysanthemums and roses, place cards, and candies. After the meal, everyone helped to wash dishes. Then they played games and did some fortune telling until it was time for a supper of leftovers from the noon meal. They played more games or went out for further entertainment in the evening. When the students came back to the rooming house, they finally turned to their unprepared lessons for Friday and dreamed of "how we could possibly bluff through the long, weary hours of the coming day."

The celebration for 1921 featured a remarkable new addition: an all-college dance. Social dancing had been a matter of considerable controversy at the college for a long time. Many faculty and administrators had opposed dancing on moral and religious grounds while students increasingly favored it, especially in the changing social climate following World War I. The college finally did approve social dancing on campus. Over 900 attended the 1921 Thanksgiving evening dance in the East Gymnasium. Admission was twenty-five cents.

A College Eye editorial writer in 1922 advised readers simply to thank someone who had helped them to become the persons they were. Students enjoyed a costume ball in 1924, but they also joined alumni guests at the ground-breaking ceremony for the Campanile.

Getting this project underway, after ten years of planning, was a significant step for the college and its alumni. Similarly, in 1925, the college opened the new West Gymnasium on the Saturday after Thanksgiving.

Football took center stage in 1928. The Teachers College team needed a victory over Des Moines University to become champion of the Iowa Conference. The big game was scheduled for Thanksgiving Day in Des Moines. The band raised over $400 to cover lodging and train fare so that they could accompany the team. The band traveled to Des Moines on Wednesday and were up early Thanksgiving morning to play an hour-long concert on WHO radio. After that, they marched into downtown hotels where Teachers College supporters were staying. The band played rousing tunes and gave school yells in the hotel lobbies before marching out to the game site, where they continued their performance. Teachers College beat Des Moines University, 12-7, and won the Iowa Conference championship. The band then enjoyed a turkey dinner at a downtown hotel with O. R. Latham, the new President of the Teachers College, and other school supporters. They boarded the midnight train and arrived in Waterloo at 3 o'clock in the morning. They then took buses back to Cedar Falls. And everyone was ready, more or less, for Friday morning classes.

The College Eye is remarkably quiet about Thanksgiving during the 1930s. Editorial writers are notably silent on the usual holiday-related platitudes and sentiments. The academic calendar that scheduled classes on the Friday after Thanksgiving continued to be in effect.

In most years there were small parties and dances in late November, but only the "Turkey Strut" dance claimed any connection with the holiday. Perhaps the extremely difficult economic situation of those days made students concentrate more on the serious side of school. Few students had any extra money for frivolous activities. But perhaps there are other factors involved. One such factor might be a change in reporting style; student journalists seemed no longer to believe that it was important to report campus news as if it were a tiny version of high society, with genteel parties, receptions, and "entertainments". The College Eye began to look less like the society page of a small town weekly and more like a city newspaper. Another factor might be the rise of Christmas as a major and commercial holiday celebration. The newspapers immediately following the Thanksgiving break during the 1930s did not look back to review the holiday just past. Instead they tended to look forward to upcoming Christmas-related activities such as the traditional Messiah performance, concerts, plays, and dances. Commercial advertisers also used Christmas themes to promote their services and products. By the 1940s, ads and references to Christmas began showing up before Thanksgiving.

In 1941, with World War II underway in Europe, and the attack on Pearl Harbor just a couple of weeks away, the newspaper interviewed students, faculty, and staff regarding things for which they were thankful. The resulting list had strong patriotic themes. Over half of the students and staff mentioned their thankfulness for living in a free, democratic country. The editorials shortly before Thanksgiving in 1942 also continued in a serious tone. The writer said that, in addition to thankfulness, Americans needed to demonstrate "vigilance and defense of the things that we are thankful for." In that writer's eyes, the enjoyment of freedom included responsibility for its defense. Despite the war, students on campus in 1942 did enjoy an all-college Thanksgiving party with dinner and singing. And, for the first time in many years, final examinations for the fall quarter were given before the holiday, so that students could go home for several days before the start of the winter quarter. Those were especially busy times on campus as students moved out of Bartlett Hall to make way for the WAVES training detachment that arrived in December 1942.

The WAVES, the women's branch of the United States Navy, and, later, the Army Air Corps each moved thousands of women and men through training classes on the Teachers College campus. They were separate from the college instructional program, but they shared the campus and the facilities. In 1943 the college somehow secured enough food to put on a wonderful Thanksgiving meal for the WAVES. One WAVE responded by writing: "When it comes to food, this college can really prepare it. This Thanksgiving dinner was the next best thing to being home." But with the blessed arrival of peace in 1945, apparently some of the emotion associated with the holiday dropped away. Faculty member Dorothy Koehring wrote that she regretted not hearing any expression of thankfulness, even though the United States was celebrating its first peace-time Thanksgiving in a number of years.

Observation of Thanksgiving in the late 1940s seemed quiet, perhaps due to the no-nonsense attitude of the many veterans who returned to campus, or perhaps due to post-war austerity.

In 1947 the federal government proposed a "meatless Tuesday" program to help deal with the perceived shortage of meat in the United States. Campus food service cooperated with the program and served only fish and poultry on Tuesdays. It is not apparent how the program affected the supply of turkey at Thanksgiving.

In 1950 the academic calendar changed again, but it did preserve the Thanksgiving break. Classes ended at noon on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving and started again on the Monday after the holiday. That year Lawther Hall residents raised $75 to assist fourteen needy Cedar Falls families with their Thanksgiving meals. In 1953, for the first time, the college declared that the day after Thanksgiving and the day before Christmas were holidays for staff members. Prior to that time, these had been ordinary workdays. Reports on campus Thanksgiving holiday celebrations during the 1950s were limited, though a College Eye writer in 1959 did express disappointment that the national cranberry contamination scare would mean that few people would have this welcome dinner treat.

Declaring that the stretch of classes between Thanksgiving and Christmas spoiled the enjoyment of both holidays, one writer in 1960, with tongue planted firmly in cheek, called for vacation to begin before Thanksgiving and end only after Christmas. Another letter writer in 1965, who stayed in town over the Thanksgiving break, was disappointed that the new library was closed during that period. He thought that a significant number of students needed access to the collections in order to catch up on their studies.

During the Vietnam War era, the Northern Iowan was quiet about Thanksgiving, but in 1973 it reported on a Hagemann Hall project that provided food for needy local families. In that same year, however, a student lamented that the holiday seemed to have lost its meaning: people were concerned only with eating and getting ready for Christmas.

A list of things for which to be thankful appeared again in 1978, but this list took on a sarcastic tone. The writer said that he was thankful that:

- The football season was over

- Towers was still standing despite rumors that coed housing would bring on its doom

- Campbell Hall and Lawther Hall still maintained the moral standards for the campus

- The new general education requirements ensured the variety (not to mention the confusion) essential to a well-rounded education

- No car accidents were reported on Hudson Road

- UNI was recognized twice in the Des Moines Register: once as a drunken, fun-loving suitcase college and the other when 9000 Northern Iowans were stolen

- The Writing Competency Examination not only ensured the literacy of UNI graduates, it also speeded up the de-tripling process

- There were no reports of roommate killings

- The UNI-Dome was still up!

In 1979 the Campus Ministries organized a fast, with money saved to be contributed to those around the world who did not have enough to eat. In the early 1980s, the Culture House, now known as the Center for Multicultural Education, began its own tradition of preparing a Thanksgiving meal. In that same period the library began to offer hours on the weekend after Thanksgiving. In 1986, the academic calendar was adjusted once again to allow the break to begin on the Tuesday evening before the holiday. In 1988 the Northern Iowan published a two-page spread on Thanksgiving cooking, and, in a bow to the rising interest in physical fitness, also offered tips on avoiding over-eating. In that same year, a Bartlett Hall resident organized a traditional Thanksgiving meal for international students who were staying on campus over the holiday.

References to Thanksgiving in the 1990s are predictable and decidedly secular. Recipes, histories of the holiday, and humorous lists of things for which to be thankful have predominated. The 1996 recipes recognized the increasing numbers of vegetarians and included several non-meat alternatives. A 1994 list of things for which to be thankful included infomercials, general education classes, the Home Shopping Network, and certain campus sculptures that seemed to invite decoration with underwear. In 1997 an editorial writer offered the following list of things to do at home over the break:

- Free laundry

- Do not get up before 10AM

- Work on your resume

- Spend a day with the family

- Eat a lot

- Get a head start on the project that's due during finals week

- Refrain from eating ramen noodles and mac & cheese

- Control your Email withdrawal

- Go shopping in the family cupboard

- Nothing

A more serious list from 1998 added freedom of speech and the opportunity to go to college to the things for which to be thankful. A columnist in that same year offered a fond look at his family's traditional Thanksgiving celebration. And rounding out the century, an editorial writer in 2000 made a case for an entire week of vacation at Thanksgiving. The writer claimed that many students and faculty were already skipping classes on the Monday and Tuesday before Thanksgiving.

How will future Thanksgivings be celebrated and noted at UNI? Almost certainly we will continue to see histories of the holiday, recipes, calls for adjustment of the academic calendar, fond memories of home, and lists of things for which to be thankful. In the event of war or other national crisis, will we see a return to more traditional celebrations and traditional, serious values? If the university adopts a calendar that calls for an entire week's vacation around Thanksgiving, will the holiday simply disappear from sight on campus? If the past 125 years of UNI history are any indication, the holiday will still center around good and plentiful food, reunions with family, entertainment, and at least a few moments of thoughtfulness about the welfare of ourselves and others.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson; scanning by Library Assistant Gail Briddle, November 2001; updated, February 6, 2015 (GP); photos updated and citations added by Graduate Assistant Eileen Gavin, May 1, 2025.