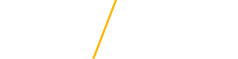

Central Hall (1869)

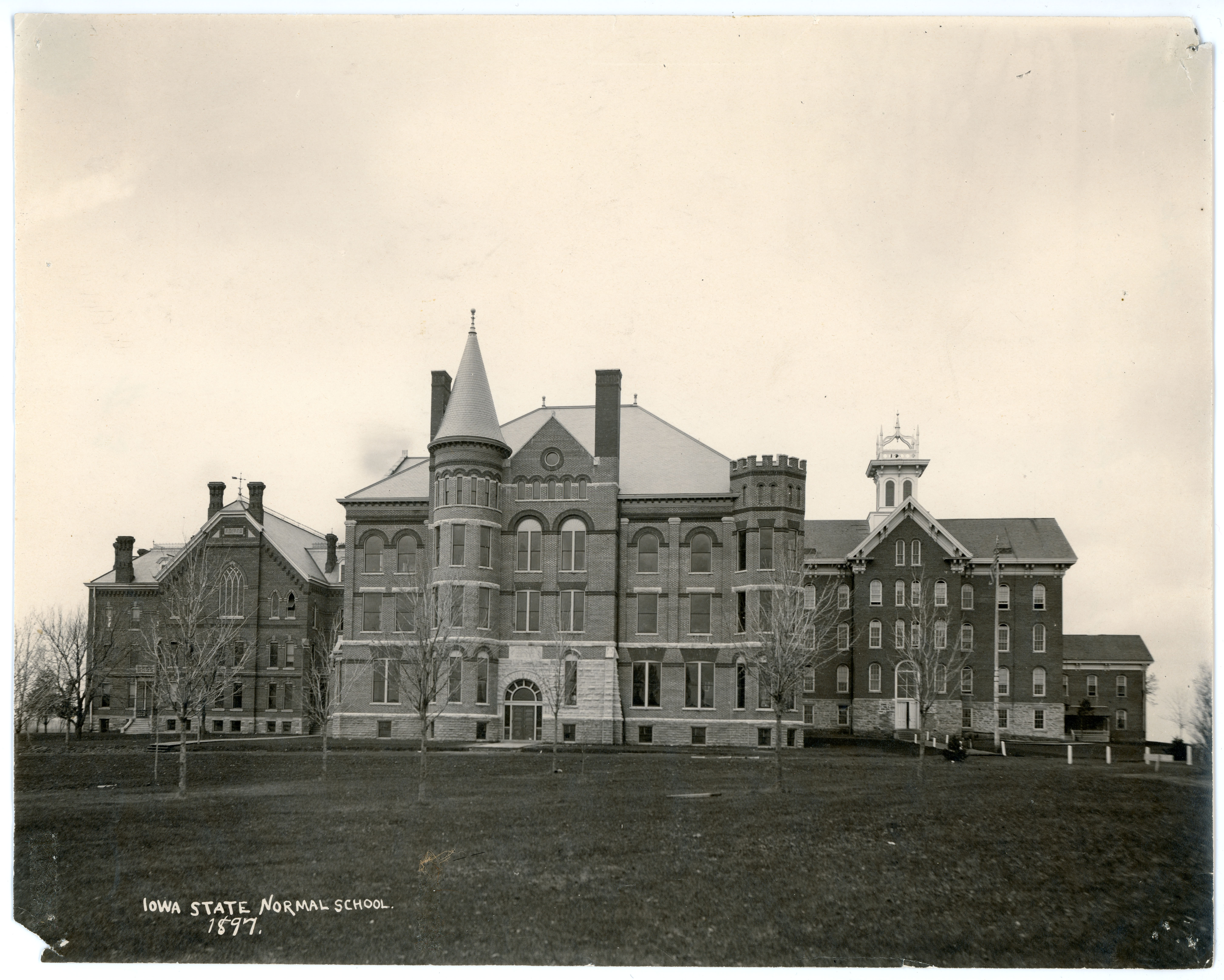

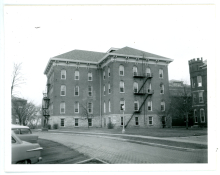

When the first classes were held at the Iowa State Normal School on September 6, 1876, only one building provided classroom space. The building, which would later become known as Central Hall, stood approximately where the Maucker Union Expansion is located today. Central Hall was built in 1869 as one of Iowa's Soldiers' Orphans' Homes. Its purpose was to house children orphaned by the Civil War.

When constructed, the tall building was alone on a prairie hilltop. The surrounding land was open to the east, south and west, except for an occasional farmhouse. Orphans moved into the still incomplete building on October 11, 1869 during an outbreak of typhoid fever. They were temporarily housed in an old hotel at Fourth and Main Street in Cedar Falls. Those who could walk to the building did so while others rode in a wagon. At the time, there were no windows or doors, and the floors were covered with plaster from the newly-plastered walls. Water had to be hauled to the building because the well was not yet finished. Once completed, the building provided a home for hundreds of orphans over the next seven years.

Children eventually grew up and left the Home. In 1876, when the state consolidated services in the Orphans' Home in Davenport, the Cedar Falls Home closed. The state was left with the prospect of a vacant building in Cedar Falls. Following heated debate and close votes, the General Assembly approved funds to start a state school for the training of teachers in the old Home.

At first, the building was referred to simply as the Normal School Building or “the Building.” After a new structure, later known as Gilchrist Hall, was built just south of the original Home in 1882, the older building became known as North Hall. As the campus developed further to the north, south and west after the turn of the century, the original building was called Central Hall or Old Central.

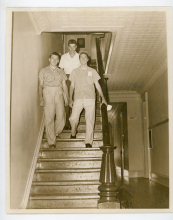

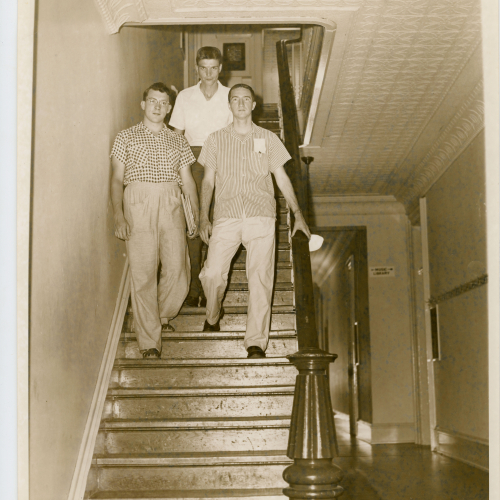

In the earliest years of the new normal school, nearly all the school's activities took place in this four-level brick and limestone building. The basement contained the dining room while the first floor rooms were remodeled into offices and classrooms. The second and third floors were used as dormitories. Students paid $2.65 per week for room and board. During the school's first year, 1876-1877, women lived on the second floor, and some men lived on the third floor. In 1877, the men moved from Central Hall to a small outbuilding, used during the Orphans' Home era as a chapel and office. Later, several classrooms were created on the second floor of Central Hall by removing partitions in the dormitory.

Women's dormitory facilities then occupied the remaining part of the second floor and entire third floor. The building had a bell, housed in an ornate cupola, which signaled activities such as meals, class change times and lights out. Students would occasionally climb up through the attic and into the bell tower to view the surrounding countryside.

Initially, Central Hall was sparsely furnished. The Orphans' Home administration had taken almost all its equipment when moving to Davenport, and the General Assembly had provided little to take its place. Sections in the building were partitioned into dormitory space, with windows in only a few of the small bedrooms. Kerosene lamps provided light. A steam plant, maintained by campus engineer Alexander Martz, provided heat. There was running water, but it was limited to a few taps in the building. Maude Gilchrist, daughter of Principal James Cleland Gilchrist, wrote about the water system: "We drew a pitcher of cold water from the big pipe, then let the steam from a nearby pipe bubble into the pitcher . . . ."

Initially, Central Hall was sparsely furnished. The Orphans' Home administration had taken almost all its equipment when moving to Davenport, and the General Assembly had provided little to take its place. Sections in the building were partitioned into dormitory space, with windows in only a few of the small bedrooms. Kerosene lamps provided light. A steam plant, maintained by campus engineer Alexander Martz, provided heat. There was running water, but it was limited to a few taps in the building. Maude Gilchrist, daughter of Principal James Cleland Gilchrist, wrote about the water system: "We drew a pitcher of cold water from the big pipe, then let the steam from a nearby pipe bubble into the pitcher . . . ."

Principal Gilchrist's son Fred wrote about the rudimentary educational equipment. He said the school "had blackboards and chalk and nothing else but bare walls and a few school seats . . . the pupil could look at the picture in the textbook and at a few diagrams on the blackboard and that was all there was to it." As for a library, "There was no library at all except some books which had been left behind by the orphans…" Principal Gilchrist provided his own books to serve as the school's library in the early years.

In fall 1878, Central Hall received its first significant improvements designed to make the building better suited for the school's mission. The campus newspaper, The Students' Offering, of December 1878, noted the following changes:

- partitions were removed to enlarge the assembly room

- additional blackboards were installed

- new floor coverings were laid

- the Principal's book collection was moved to the parlor

- walls were painted

- the physics and chemistry laboratory received apparatus valued at about $800

The writer of that article concludes by saying, "Taking all together, we are very happily situated."

The next year, an additional classroom was carved out of the dormitory space on the second story, and the school acquired a new piano, which was placed in the music room. On April 18, 1880, a storm blew down one of the chimneys on Central Hall. The bricks fell through the roof and down to the attic floor, but the partitions on the third story kept the bricks from falling further into the building. No one was injured. Damage to the chimney and other campus property was estimated at $50-$60. One of the tall chimneys would again be blown down in a 1892 storm. During summer 1880, the state spent about $700 on new carpets, paint, wallpaper, and bookshelves, and Principal Gilchrist's classroom was outfitted with new seats. By 1880, the parlor was converted into a library and reading room, with a student librarian in charge of the newly classified and catalogued collection.

Central Hall witnessed the introduction of late 19th-century technology to the Normal School. During the 1878-79 school year, students gathered to see a new phonographic recording machine. As alum Ella Rich Rundles (1882) recalled over 40 years later, Professor William N. Hull spoke into the recording device so his voice would be preserved on the foil medium. She said, "It went through all right, but sounded more like the squeaking of a mouse than the voice of our rhetoric teacher. However, it could be distinctly heard all over the room--a wonderful invention."

Another new technological advance came to campus in 1881 when a telephone was installed in Central Hall. This was likely the first telephone on campus. It connected to both Waterloo and Cedar Falls. A writer in The Students' Offering noted the telephone "saves many weary tramps downtown for 'that little thing that I forgot.'"

In 1892, the General Assembly appropriated $5,000 for additional repairs to Central Hall. This was meant to soften the blow of delaying funding for a badly needed new building. The money would be used to refit Central Hall with additional classrooms. Increased enrollment drove the Board’s decision to discontinue the school's boarding department, housed primarily in Central Hall, and remodel the space for educational purposes. There was also consideration of building a bridge between Central Hall and Gilchrist Hall. With the discontinuation of the boarding department and consequent elimination of the basement dining room, the alumni held their annual banquet in Central Hall for the last time in 1892.

By September 1892, Central Hall looked different. The basement had been fitted as an armory and drill room for the student battalion. Cadets had easy access via the west door. Also included were a chemical laboratory and a storage area for athletic equipment. Women's calisthenics classes met in the armory that fall but later moved upstairs due to high enrollments. The parlor and an adjacent room on the first floor were combined into a large classroom. There were also two large coat rooms and a book room on that level. The second story included two classrooms and space for preparatory and training school students. The third level remained the same, although plans were made to build literary society halls. Society bulletin boards remained in the vestibule of Central Hall.

Infrastructure improvements took place just north of Central Hall in 1892 when a new cinder roadway was built over the former croquet grounds. Later that fall a new elevated walkway between Central Hall and Gilchrist Hall was under construction and finished by the end of the school year. The student newspaper, now called the Normal Eyte, noted, "This is a most desirable addition to Normal architecture that will be most highly appreciated by all students. Now let the winds howl and the rains descend! What care we!" While the bridge had the potential to increase the efficiency of passage from building to building, students would occasionally, and intentionally, cause a traffic jam on the bridge to delay arrival at their next class.

In fall 1892, students also began to agitate for "bathrooms" in Central Hall. In this case, the word "bathroom" was literal: facilities where students could take a bath. Bathrooms were ultimately built under the auspices of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA).

In fall 1893, the preparatory department moved into the third floor of Central Hall, although the literary societies were still searching for rooms on that floor. The Board was willing to provide the third story to the societies if the societies were willing to undertake the cost of remodeling. The societies met at Commencement in 1894 and drew up recommendations to divide the third story into three large rooms, with a budget of about $1,200 for construction, decoration and furnishings.

In fall 1895, the long set of exterior steps on the east side of Central Hall, often icy and dangerous in the winter, were removed, the doorway was lowered and a large window was inserted above the door, which had been lowered to ground level. Interior stairs substituted for the exterior steps. This resulted in more light inside the main hallway. Also, the drive on the east side of campus was moved to the rear of the buildings to provide more green space in front.

When space in the new Administration Building opened in January 1896, Central Hall experienced even more changes. The second and third floors were devoted entirely to the Training Department, a precursor of the Laboratory School. During summer 1896, the third story received new flooring and furniture, and in summer 1897, much of the interior was painted and papered. A writer for the the Normal Eyte commented, "At no time during the past ten years has the building been in as good repair throughout."

In early 1898, with enrollment continuing to grow, the men's coat room was shifted from the first floor of Central Hall to the basement to make room for a new, enlarged women's coat room. In 1901, during the construction of the Auditorium Building (now Lang Hall), a link later known as the Crossroads was built between the new building and the Administration Building. A corridor extending west from the Crossroads to Central Hall meant all four of the school's major buildings were connected. Students could attend classes in any building without going outdoors.

Over its long history, Central Hall was used for many purposes, which required modifications. For example, in 1905 the gables and decorations atop the bell tower were removed. The bell itself continued to announce the beginning and end of each school day until at least 1926. Thereafter, it was rung only to mark special occasions such as February 28, 1931 when a small group of students rang the bell to celebrate a basketball victory. They then escaped by running across the roof and down a fire escape. Later the bell would be used to announce Cut Day on campus. Despite its age, Central Hall served as an important classroom building for many years.

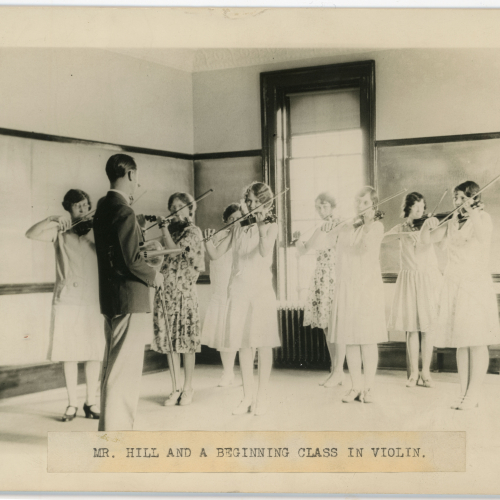

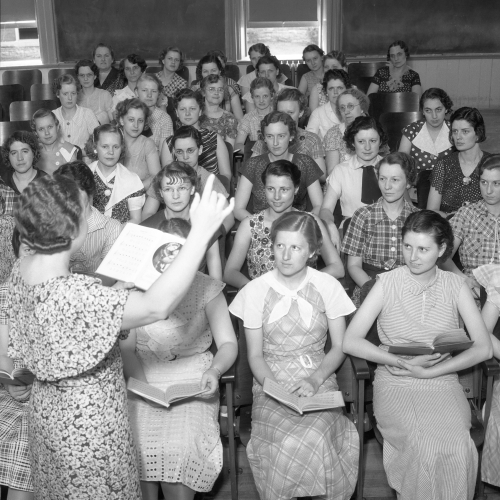

When President Latham began his administration in 1928, one of his primary aims was increasing the efficiency of college operations. Consequently, he consolidated the locations of various instructional departments, whose faculty and classrooms had been scattered across campus. The Commercial Department, which had occupied a portion of Central Hall’s third floor, moved to the Administration Building, and the music faculty and classrooms moved into Central Hall. The YMCA, campus supply office and student club rooms occupied Central’s basement. The YMCA also operated a small convenience store where students could buy candy and pop. In addition, the college outfitted a new band and orchestra practice room in the building accommodating about 60 musicians. The room was arranged in tiers, with individual lighted music stands. Professor Myron Russell, who directed the College Band, thought the new facilities contributed to the improvement of the group.

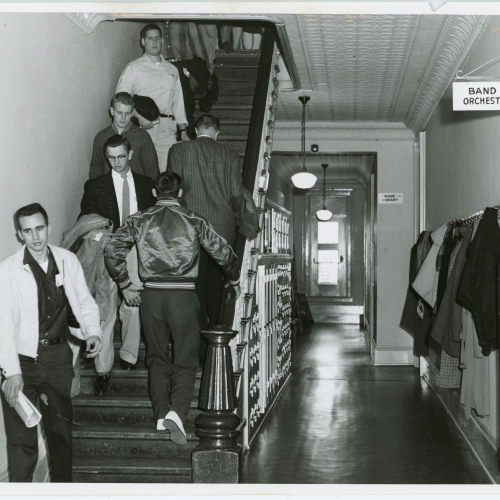

Again, Central Hall underwent significant remodeling in the summer of 1932. Some improvements were general while others were designed specifically for the Music Department. New linoleum was installed throughout most of the building, and some of the stairways were reconstructed. Drinking fountains were installed on all floors. New gutters were added in May 1933. The department received a new music library with books, records, a phonograph, and sheet music, and Music faculty received private offices.

In 1934, the Bureau of Research, directed by Professor Joseph B. Paul, was established on the second floor of Central Hall. Later in summer 1936, the college Mimeograph Room moved to Central Hall.

The Music Department became so closely identified with Central Hall students sometimes referred to it as “the Music Building.” In 1937, one College Eye writer said he had trouble writing for newspaper deadlines while the sounds of piano, voice, organ and clarinets rang in his ears.

In 1947, President Malcolm Price announced plans for campus development calling for the replacement of the three oldest buildings: Central Hall, Gilchrist Hall, and the Old Administration Building. However, all three remained in use for several more years. In 1953, Central Hall received a new roof to replace the spring hailstorm damage and its exterior trim was painted.

In summer 1956, Registrar Marshall Beard spoke to a Phi Delta Kappa meeting about the campus changes he expected in coming years. Among those changes was the elimination of the three buildings noted by President Price a decade earlier.

In 1959, the General Assembly appropriated $2.57 million for new construction on campus. Included in the plans was a new Music Building. An article in the Alumnus noted Central Hall, where much of the Department of Music was located, is "Now obsolete and hazardous from the standpoint of fire, and even dangerous because of structural weakness…"

In 1962, when the Music Department moved from Central Hall and to Russell Hall, the top floor was closed. Officials cited narrow stairways among the hazards of the old building.

After the departure of the Music Department, Central Hall housed a few classrooms, the remedial reading clinic, the mimeograph office and offices for sixteen faculty members in the Department of English Language and Literature. Dean of Instruction William Lang announced as soon as space for these occupants could be found in other buildings, Central Hall would be demolished, perhaps in another ten years or so. Although still in use, many of the building’s original features had been removed to keep the building in working order.

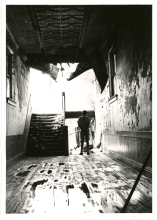

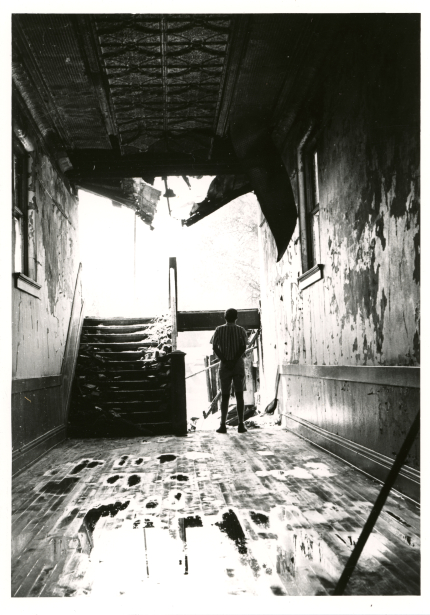

On the night of July 22, 1965, Central Hall burned in a fire later determined to have been caused by faulty wiring. College Eye managing editor Kent Speirs discovered the fire as he was leaving the newspaper office in Old Gilchrist Hall at 12:40 AM. He informed a campus security officer that he saw smoke coming out a window. They entered Central Hall in an attempt to investigate but were driven back by smoke and heat. The Cedar Falls Fire Department, later aided by the Waterloo and Dike Fire Departments, attempted to control the fire without success. The fire spread from the first to second story, then to the third story and roof. Firefighters kept the fire from spreading to other nearby buildings. By morning, Central Hall was a total loss.

Faculty members lost the contents of their offices - books, class notes, research material - in the fire. Professor Robert J. Ward, of the English faculty, lost his nearly completed doctoral dissertation. He had an early draft stored at home, but said it would likely take him a year to bring that version up to date.

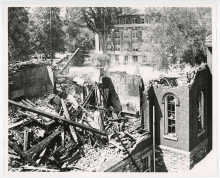

Because firefighters feared some of the remaining brick walls would collapse onto other buildings, a crane pushed the walls onto the smoldering pile of wreckage. Cleanup of the site and repairs to the Crossroads continued for months afterward.

The college was left with significant scheduling problems in the wake of the fire. Summer classes could be relocated. However, fall semester presented a more difficult situation. The college had planned to continue using Central Hall for classrooms and 34 faculty offices. The Registrar re-scheduled most of the classes for Sabin Hall. Faculty members with offices in Central Hall dispersed across campus.

The fire in Central Hall had other implications. Rather than replacing the building, the Regents decided to fund an addition to the newly-completed Administration Building, now known as Gilchrist Hall. This $631,000 project added 27,504 square feet to the east side of the Administration Building. In addition, the old Reading Room in Seerley Hall, which served as the campus library until 1964, was converted into classrooms.

The state fire marshal visited campus on an inspection tour in summer 1965 and left a long list of hazards needing corrections. With the recent fire in Central Hall, campus officials made significant efforts to improve wiring, clean out attics and basements, and eliminate wooden blocks used to prop doors open. The report also helped the administration make a stronger case for newer, safer facilities.

Compiled by Library Assistant Susan Witthoft; edited by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, July 1996; substantially revised by Gerald L. Peterson, with scanning by David Glime, August 2006; updated January 28, 2015 (GP); photos and citations updated by Graduate Assistant Eliza Mussmann, May 5, 2022; content updated by Graduate Assistant Marcea Seible, May 2025; updated by Library Assistant Hannah Bernhard, January 2026.