Am Good as Common: Thomas E. Seerley's Journey to the Montana Goldfields in 1864

Biographical sketches of Thomas E. Seerley and Louisa Ann Smith Seerley, written by their son, Homer Horatio Seerley, with additional information compiled and furnished by Stan Culley, a great-great grandson of Thomas E. and Louisa Ann Smith Seerley.

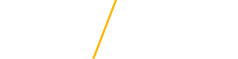

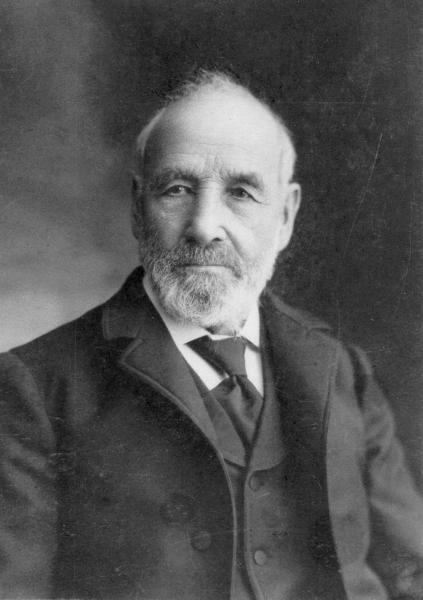

Thomas E. Seerley

Born: April 20, 1821, Frederick, Maryland

Died: October 18, 1904, Iowa City, Iowa

Buried: Fairview Cemetery, Cedar Falls, Iowa

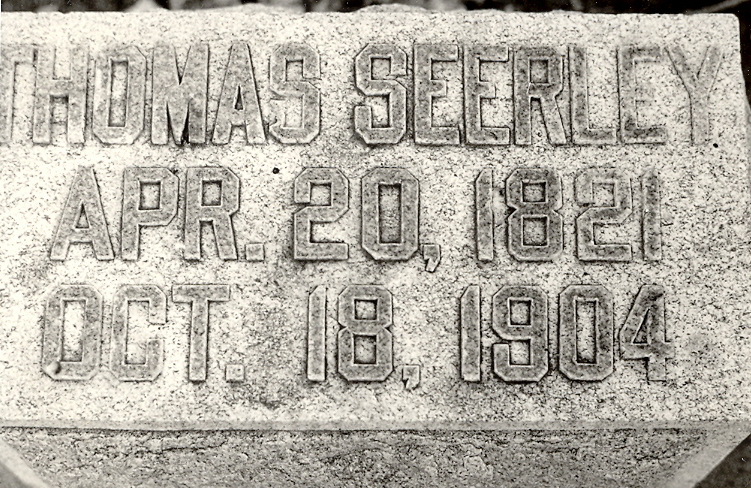

Louisa Ann Smith Seerley

Born: November 9, 1826, Indiana

Died: June 15, 1914, Iowa City, Iowa

Buried: Fairview Cemetery, Cedar Falls, Iowa

Thomas E. .Seerley and Louisa Ann Smith were married October 4, 1846, near Indianapolis, Indiana

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thomas E. Seerley, by their son, Homer H. Seerley

When Thomas Seerley was not yet of age, he walked from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Baltimore, Maryland, helping drive a large herd of cattle to market. After visiting relatives in Maryland and Pennsylvania, he walked the entire distance on the return trip. As a consequence, he had most accurate information regarding the sections of the country through which he passed.

When he was just over age, he made a trip by flatboat to New Orleans and spent the entire winter season chopping logs in the great lumber regions of Louisiana. He returned satisfied to remain permanently in the North Central states.

In 1863 [1864], he made a trip by ox team from South English, Iowa, to Virginia City, Montana. He started to go to Oregon to see if it was a satisfactory place to take his family, but found the distances too great to encourage him to go further than Montana. He earned enough money by working in the placer mines at Virginia City to return home after two summers' absence. In his diary, he gives a brief account of the trip and pays attention to the Gallatin Valley as a superior place in which to live.

He was Justice of the Peace for eight years while residing on a farm near South English, Iowa, and was accorded a notable reputation for his judicial work during that time and also for his accurate knowledge of the Iowa statutes.

He combined teaching school and farming in his early life in Illinois and Iowa. His work as a teacher was thorough, scholarly, and notably successful. He had a very large part in the elementary education of his sons and gave them more care, more instruction, and more benefit than all the teachers employed. Every night during term time he looked after the studies pursued by the boys and helped in all their difficulties. There was never found a proper arithmetical problem of any kind that he could not solve.

He was a Worshipful Master of Naphtali Lodge No. 188 A. F. and A. M., located at South English, Iowa, and was one of the best posted and most capable workers in that order. He initiated, passed, and raised all of his sons while master of this lodge and instructed them personally in the work and the usages of Freemasonry as applied to the Blue Lodge.

He was a companion for his sons all during their childhood. He played athletic games with them, he took them fishing, swimming, and on social trips and enjoyed everything they enjoyed and he planned to have them interested and successful in all kinds of work that was on the farm and in the community. In all this he was a factor himself and could do as large a day's work and do it with as fine a spirit as any man that ever lived.

He made the home a place where the boys could have the best of times. He cultivated in them respect for religion, esteem for morality, and desire for the best habits. In all these things he was a noble exemplar, and a better type of personality and character they could not find. He was a student of the highest order and did all his work using his head as well as his muscles and his strength in everything he undertook.

In all of these things he was seconded and helped by his wife, a true helpmate and devoted woman. She never left anything undone that was able to be done at the time under consideration, and she worked co-operatively with him for the welfare and the progress of their children in training and in development.

Both Thomas Seerley and Louisa Ann Smith Seerley were possessed of the best health and physical constitution both were energetic and enterprising. Both were suited to pioneering and to meeting the hardships of early settlers in a new country. Both were ambitious for the better things of life and were active factors in the social and religious advancement of the community. Thomas Seerley was not addicted to any bad habits of any kind and never used intoxicating liquors of any variety or even tobacco, although both were common practices in his boyhood and in his early manhood. He worked in a distillery in Pennsylvania where whiskey was free to employees and yet his principles of sobriety maintained him. When a young man, he united with the "Sons of Temperance" and, after that, even declined to drink cider on account of the fact that much of it was hard and contained alcohol. He saw so much gambling in his boyhood and had such knowledge of it at Virginia City, Montana, that he never learned to play cards and declined to permit his boys to to the same on account of the associations that they had to him with evil men. His knowledge of the dancing of the period and of the "hoe-downs" that existed in Iowa led him to require his sons to keep away from such associations and experiences.

While he played a violin very well for a pioneer and needed money very badly many times during pioneer days, he refused to play the violin or assist in the music at these dances, notwithstanding the high prices paid for such services.

Louisa Ann Smith Seerley was a remarkable business woman, maintaining the family on the money she made by selling butter and eggs and other home products. She was economical and efficient at the same time. She made all the clothing of her boys until they were ready to go to college, and she did all the housework and farm work without any help for herself as the woman of the household. She did this even without assistance when harvesting, threshing and other work required a large number of workmen to be fed. It seems very remarkable that she had such strength and capability when it is recalled that she was a small woman, weighing 99 pounds at 20 when married and never more than 108 pounds until in her later life.

Thomas Seerley was a man of 5 foot 11 1/2 inches stature, weighing 180 pounds in his young manhood, wore a number eleven shoe, and had a physique that permitted him to have few competitors. He was a skillful farmer and practiced most of the things that are now counted as modern farming. He was an equally skillful hunter and in the pioneer days kept his family supplied with wild meat such as venison, prairie chicken, grouse, ducks, geese, fish, and other game, as other kinds of domestic supplies were impossible. In this line he was a leader in the community. When he went into a wagon train to Montana in 1863 [1864], he kept the entire party of twenty wagons supplied with game. as long as he remained with it on the way to the Oregon country. While in Montana, he kept up the supply for his own use in the cabin he maintained for his home.

-------------------------------------------------

Obituary of Thomas E. Seerley, copied by Stan Culley from an obituary in a Cedar Falls, Iowa, newspaper

Death of T. E. Seerley,

father of President Seerley to be interred

here after an illness of almost four weeks

Thomas E. Seerley passed away yesterday afternoon at his home in Iowa City, aged 83 years. Funeral services took place from his late home in Iowa City this afternoon. The remains will arrive in Cedar Falls tomorrow morning and will be taken direct from the Rock Island station to Fairview Cemetery.

Thomas E. Seerley was born April 20, 1821, at Frederick, Maryland. In 1823, he went to Pennsylvania. Twelve years later he removed to Indianapolis, Indiana. On October 4, 1846, he married Louisa Ann Smith. In 1851, he removed to Illinois near Toulon. In 1854, he came to Iowa, settling at South English in Keokuk County, where he lived for thirty-seven years on a farm he purchased of the government. In 1891, he removed to Iowa City, where he has resided for the past thirteen years. He was an original member of the Washingtonians, the first temperance society of his youth, was a member of the Sons of Temperance, the next organized society to advocate temperance, and he has strongly maintained the cause of temperance ever since. At Toulon, Illinois, he became a member of the Masonic Lodge. At the time of his death, he was a member of the lodge at South English, having served in the capacity of Worshipful Master for a number of years at South English. He was very active in the cause of education, taught several years in Illinois and Iowa when a young man, looked after the elementary education of his family preparing them for college himself. He was s superior student of German and had an acquaintance with Spanish to sufficient extent to read it. He was a natural mathematician, a great student of the Scripture, knowing many of the Psalms, Epistles, and the Gospel by heart. By birth he was an English Lutheran, and by conversion early in life after coming to Iowa, he united with the Methodist Episcopal church of which he was a member at the time of his death. His father was a soldier of the War of 1812 and was in the trenches at Baltimore at the time of the bombarding of Fort McHenry. He is survived by his wife and three sons, Homer H., Cedar Falls; John J., Burlington; and Dr. Frank N., Springfield, Massachusetts; and one brother at Winterset, Iowa.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Louisa Ann Smith Seerley, by Homer H. Seerley

Louisa Ann Smith knew very little about her father's family. George Smith spoke the German language and came from Virginia. He told her that his father and mother were poor, land-working people, his father being a German and his mother being Irish. Euphimia Ward, the mother of Louisa Ann Smith, first married a Robert Wilson, who went from Indiana back East on a collecting trip. He obtained money from his collections and started home, but disappeared in the mountains. A diligent search was made to find him and from what is known of the dangers of such a trip under such circumstances as were revealed by the investigation, it was decided that he was murdered for his money.

Euphimia Ward Wilson married George Smith in about 1824, probably at Liberty, Union County, Indiana. George Smith had five children from a previous marriage. Louisa Ann Smith came from the union of Euphimia Ward Wilson and George Smith.

Euphimia Ward Wilson Smith was born July 25, 1797, and died October 5, 1849, a victim of typhoid fever. She was buried in a country cemetery near Broad Ripple, Indiana, called Washington Churchyard. This was originally a country Methodist Episcopal church, but it is now an abandoned burial place, and entirely neglected. There was a small marble headstone marking her grave in 1900.

After Euphimia's death, George Smith married Ann Shoemaker, but they disagreed about their younger children and were divorced with a permanent settlement. He later married a maiden woman at Frankfort, Indiana. George Smith died December 20, 1878, at Frankfort, Indiana, and was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery. His last wife was also buried there at an earlier date.

George Smith was born in Virginia near Keezeltown, Rockingham County. He settled first at Liberty, Union County, Indiana, and from there went to Indianapolis. He was a blacksmith by trade, a farmer as a second occupation, and a businessman of such capability that he became a capitalist and banker at Frankfort, Indiana, during the later years of his life.

Obituary of Louisa Ann Smith Seerley, copied by Stan Culley from an obituary in a Cedar Falls, Iowa, newspaper

H. H. Seerley's mother dies

Passed away at home in Iowa City

Death was due to decline of old age

She had been failing long

The remains of Mrs. Louisa Seerley, widow of the late Thomas Seerley, will arrive here tomorrow morning from Iowa City and will be taken directly to Fairview Cemetery for interment. The funeral service was held at her late home in Iowa City today where she lived for many years. The funeral cortege will come via the C. R. I. & P., arriving at 10AM, and will go directly to Fairview Cemetery for the interment, by the side of her husband, who died October 10, 1904

H. H. Seerley, who left here late yesterday for Iowa City, it is understood, reached his mother's side before the end came last night. Death resulted from the ailments incident to old age and followed several months of gradual physical decline. The deceased was one of God's noble women, a pioneer in the state, and one who exemplified her force of character in the rearing of her children, all of whom are men of prominence in their professions and have been loyal in their loving devotion to the mother at all times, but especially since the death of their father ten years ago left the responsibility to them. She preferred her own home and surroundings, where she had every comfort and until recent months the companionship of a brother, now deceased. Two professional nurses have cared for her and every Friday night for many weeks her sons in Iowa have taken turns in visiting her for a few hours. The sons are: Dr. Homer H. Seerley, of Cedar Falls, President of Iowa State Teachers College; John J. Seerley, of Burlington, a leading attorney of the state; and Dr. Frank A. Seerley, of Springfield, Massachusetts, head of the well known Young Men's Christian Association training schools there.

Biographical sketches written by Homer H. Seerley; obituaries gathered by Stan Culley; contents of the sketches and the obituaries edited for format and clarity by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, November 7, 2011; last updated, February 14, 2012 (GP).