Highlight: Mold Removal within SC&UA

Working in Special Collections & University Archives means that oftentimes, I am responsible for handling very delicate, fragile antiquated materials. SC&UA strives to preserve and care for these items so that they may be enjoyed and used in future research. To make this possible, staff in SC&UA, such as myself, perform basic preservation work on the materials to help extend their usable life. Sometimes the materials acquired by SC&UA are in rough shape from the long life they have lived, such as having torn or missing pages, faded imagery and text, and traces of mold.

Something new that I have learned so far this semester, in my role as the SC&UA Collections Technician, is how to deal with mold. Whether mold is live or inactive, we try to address it to prevent further damage. If it is currently something that has active mold it needs to be moved away from all of the other archival materials to prevent it from spreading.

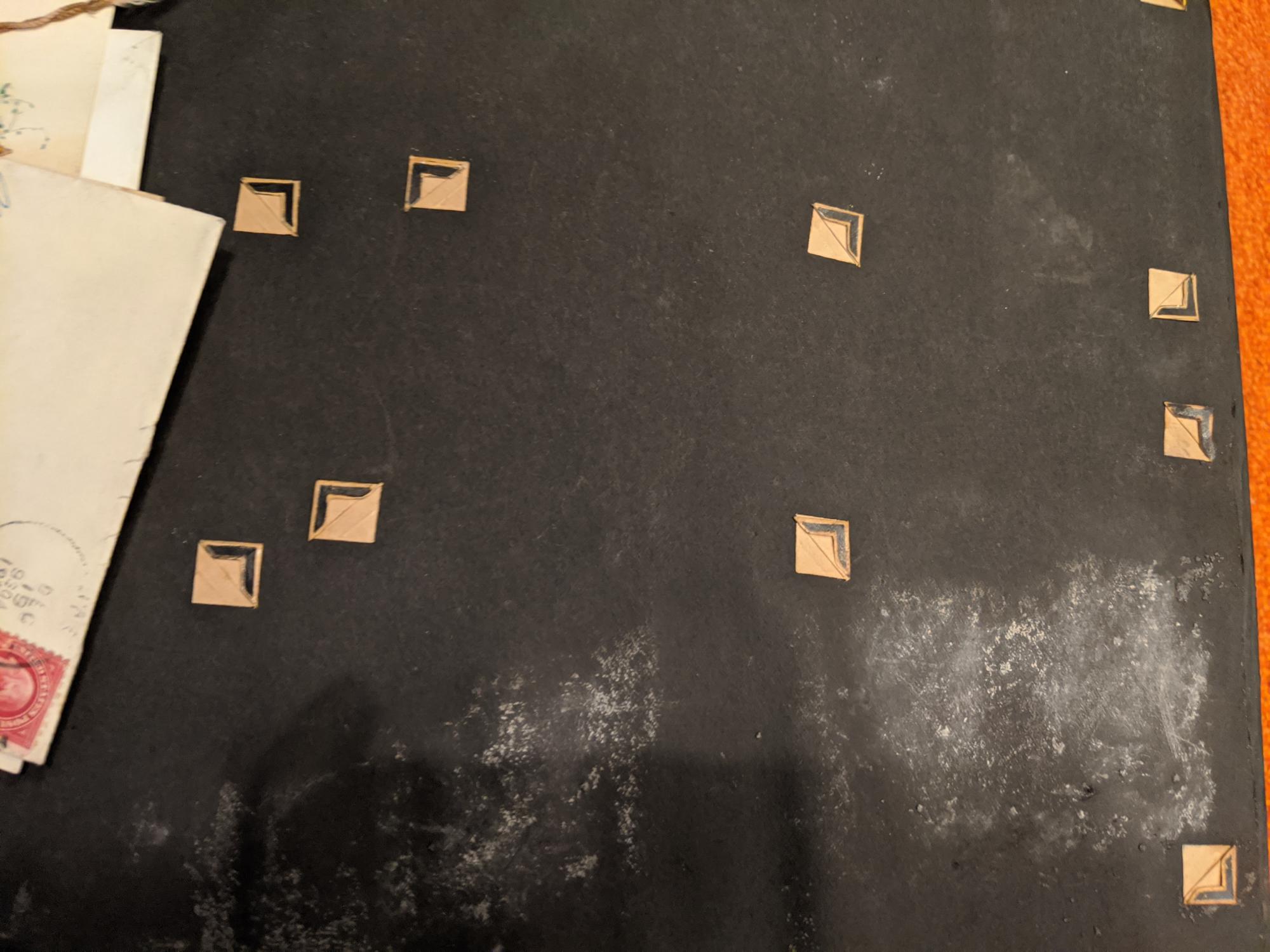

If we find inactive mold, we try to effectively and safely remove it from the material. Inactive mold means that there are traces of mold that used to be alive, but now it’s just a residue left over and is not an active threat to spreading across the collections. However because mold can go dormant but never really dies, it is important to remove inactive mold to prevent it from coming alive again in the right environmental conditions. To remove inactive mold, I spent time working in the Culture Lab, which is a reservable space within the UNI Museum in Rod Library. Nathan Arndt, the UNI Museum Assistant Director and Chief Curator, showed me how to use the different tools and equipment in the Cultural Lab.

To start, I selected a brush to gently remove the mold. The Cultural Lab has many different brushes of various sizes and softness, depending on the texture and durability of the object that you want to clean. These brushes look very similar to paint brushes, and they are used to gently brush the inactive mold off of the item and into a HEPA vacuum. This way, it prevents the inactive mold spores from getting into the air or onto anything else. This is done tediously and delicately until the residue that is able to be removed, is gone. To ensure that the mold is not active, I check it with a blacklight. With the main lights off and the blacklight on, the inactive mold appears as a gray color, while active mold comes up as more of a bright, almost neon, green color. Active mold will also physically move when tampered with, while inactive is immobile.

After brushing the inactive mold, I use some Isopropyl Alcohol and a cotton swab to clean the area that I just brushed. You don’t need a ton of alcohol for this - I just barely dipped the swab into the alcohol, then I rolled the tip of the swab on my glove to test how long it takes to evaporate, which should be almost immediately. The cotton swab tip should be gently rolled onto the surface (as opposed to being rubbed) on the item in need. In doing this, the alcohol kills off anything left over that may have not been caught before, leaving the surface safely ready to be stored and viewed once again.

For safety purposes, when I work in the Culture Lab I must wear a mask covering their nose and mouth, a lab coat, closed-toed shoes, and gloves.

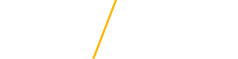

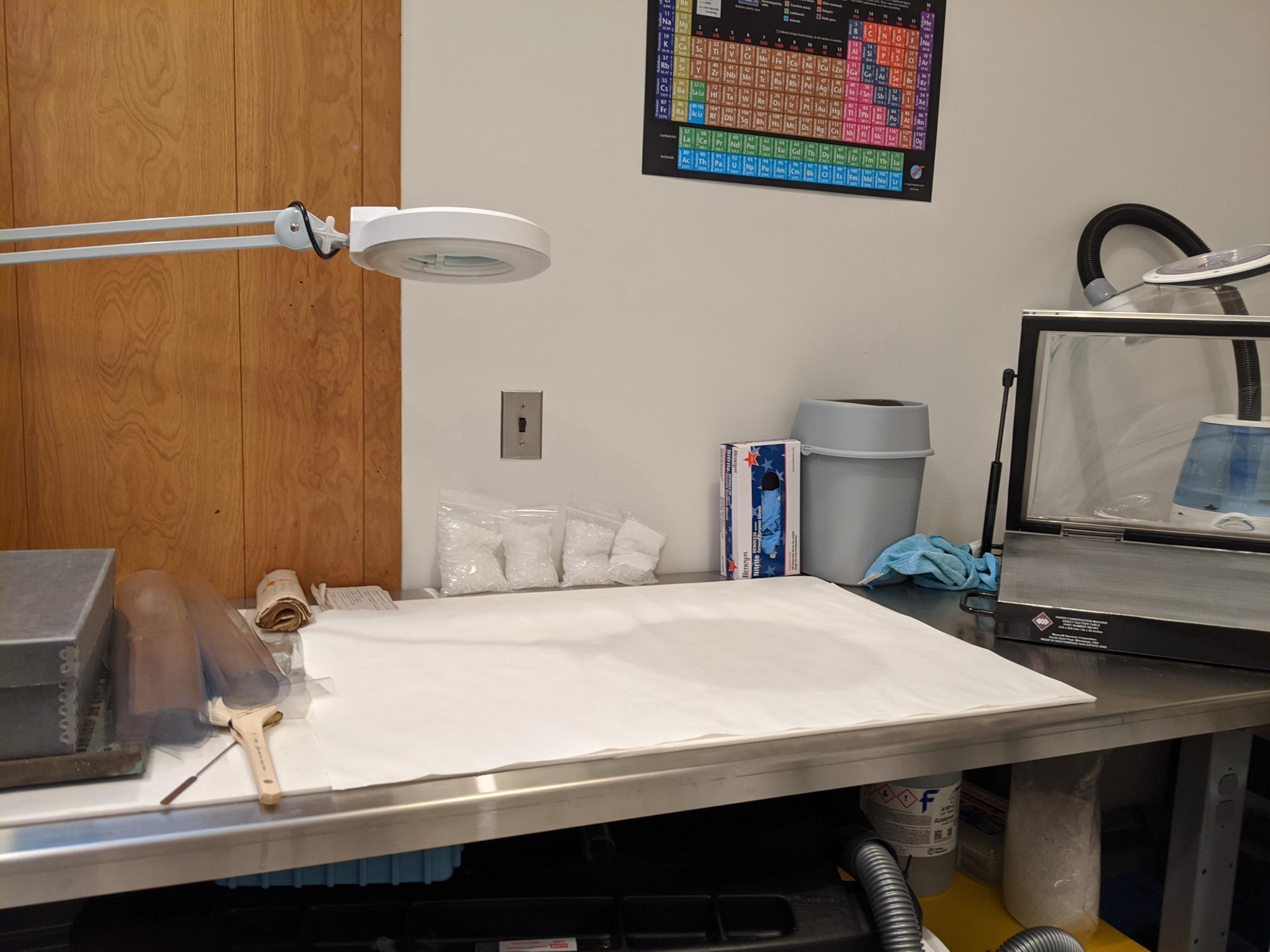

One of the materials that has just recently gone through this process is Lucille Beman's ISTC scrapbook of 1922 to 1924. In doing this we can further the care that we offer to the special collections of UNI.

Contributed by SC&UA student employee Raegan Christianson, October 2020.