Kaltenbachs : a Solid American Family, With a Shadow

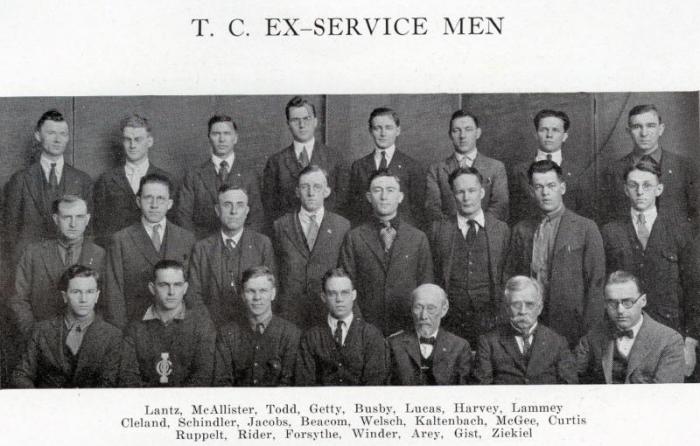

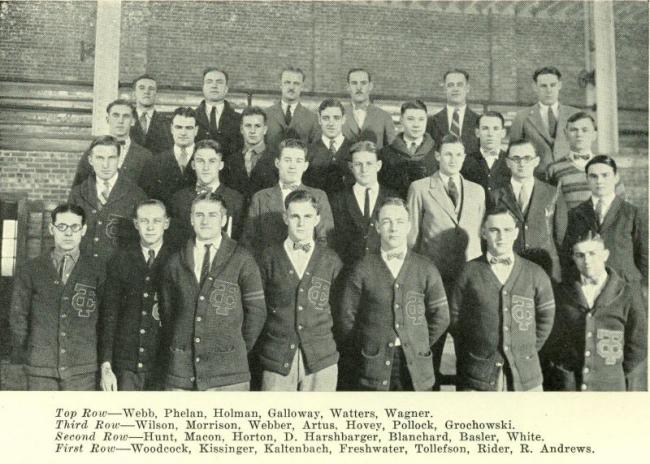

Fred, Elsie, Gustave, and Erwin Kaltenbach, Iowa State Teachers College alumni

Introduction

From 1851 through 1900, over 3,500,000 Germans emigrated from their home country to the United States. Even today, German-Americans comprise the largest single ancestry group in the United States. Students of German descent have been a significant part of the enrollment at the University of Northern Iowa from even its early days as the Iowa State Normal School and the Iowa State Teachers College. A quick and imprecise look through the register of students for 1914-1915, for example, shows that about twenty percent of students had names that suggest a German background. Given the patterns of immigration and settlement in Iowa, and especially eastern Iowa, that is scarcely surprising.

The Germans who settled in Iowa in the latter part of the nineteenth century tended to be farmers, craftsmen, or merchants. They became respected members of their communities, worked hard, upheld religious and civic values, and responded honorably to calls for American military service. They also tended to place a high value on education. They saw to it that their local public or church schools were in good shape. Some of their children went on to town or city high schools and a few even went to college.

The Kaltenbach Family

The Kaltenbach family is an example of the German immigrant experience. Johannes R. (probably Reinhard) Kaltenbach was born to Reinhard and Agathe Kaltenbach in Baden, Germany, on December 14, 1864. Johannes Kaltenbach emigrated to Dubuque, Iowa, in 1891. In the United States, the name Johannes became John. John Kaltenbach made his living as a butcher. He followed the Presbyterian faith. In 1894, he married Anna M. (probably Maria) Scheppele in Dubuque. Anna Scheppele, the daughter of Peter and Salome Scheppele, was born in Germany in January 1866. She emigrated to the United States in 1888, probably with her parents. In the United States, her name was sometimes recorded as Ann or Mary Ann.

Frederick Wilhelm Kaltenbach, the first child of John and Anna Kaltenbach, was born on March 29, 1895, in Dubuque, Iowa. He was usually known as "Fred" or "Fritz". Not long after his birth, the family moved to Waterloo, Iowa. There the family added five more children:

- Adolf Gustave, born November 23, 1896;

- Hilda Marie, born October 3, 1898, and died July 1, 1902;

- Elsie A., born October 21, 1900;

- Erwin John, born October 2, 1904;

- and Roy M., born December 16, 1906.

It is interesting to note that the Kaltenbachs, apparently becoming more assimilated in their new country, gave their last child a decidedly American first name.

John Kaltenbach became a naturalized American citizen in 1896. By 1912, and possibly earlier, the family lived at 217 Conger Street, Waterloo, Iowa, in a respectable working class neighborhood. The 1912 Waterloo city directory shows that John Kaltenbach was then working as a meat cutter for the H. A. Schmitz Meat Market at 101 E. Fifth Street in Waterloo. His wife, Anna, was working at the Chautauqua Laundry. His son Adolf Gustave was working as a driver for that laundry. By 1913, John Kaltenbach was operating a meat market of his own at 516 Lafayette, in downtown Waterloo. That business seemed to continue for some years, with his son Fred joining him there occasionally as a meat cutter. By 1919, John was operating a grocery store at 741 Riehl Street in Waterloo, but by 1920 he was working as a butcher at the Hershberger Brothers Grocery Store at 529 W. Ninth Street, on the west side of Waterloo.

John Kaltenbach continued to work at Hershberger Brothers through about 1923. Then he cut meat at the Bentley and Stoddard Grocery Store and seemed to work off and on as a butcher through about 1930. After that date, there is no occupation listed with his name in the city directories. His wife, Anna, died in 1930. John was sixty-five years old at the time. Perhaps that seemed like a good time to retire from the hard work in a butcher shop. He continued to live in the house on Conger Street until his death on May 20,1939.

The Kaltenbach family was a strong socio-economic unit. Even after they had completed their bachelor's degrees, most of the children continued to make the Conger Street house their home for a number of years. They tended to marry late. Fred received his degree in 1920 and found a job in Waterloo; he lived at home until at least 1927. Even after he found jobs out of town, Fred Kaltenbach still listed the Conger Street address as his permanent residence through at least 1936. Adolf Gustave Kaltenbach was listed at the Conger Street house through 1927. After Elsie Kaltenbach found a position as a teacher at the Grant School in Waterloo, she lived at home until at least 1925 and possibly until August 1926, when she married. Erwin John was also at home until at least 1925. Roy seems to have lived at home until his father's death in 1939. Perhaps Roy was the family's designated caregiver for their aging parents. Roy almost certainly held a job during this time, as well. The 1939 city directory lists Roy, following in his father's occupational footsteps, as a helper at the McStay wholesale meat company.

The Kaltenbach family respected the value of education. The children attended Waterloo public schools and then Waterloo East High School. Of the five children who reached maturity, four graduated from the Iowa State Teachers College in the adjacent city of Cedar Falls, Iowa. Two of them received graduate degrees at other institutions. At a time when comparatively few working class students completed, or even attended high school, sending four children to a collegiate institution is a remarkable testament to what a hardworking immigrant family could achieve in just over thirty years in Waterloo, Iowa.

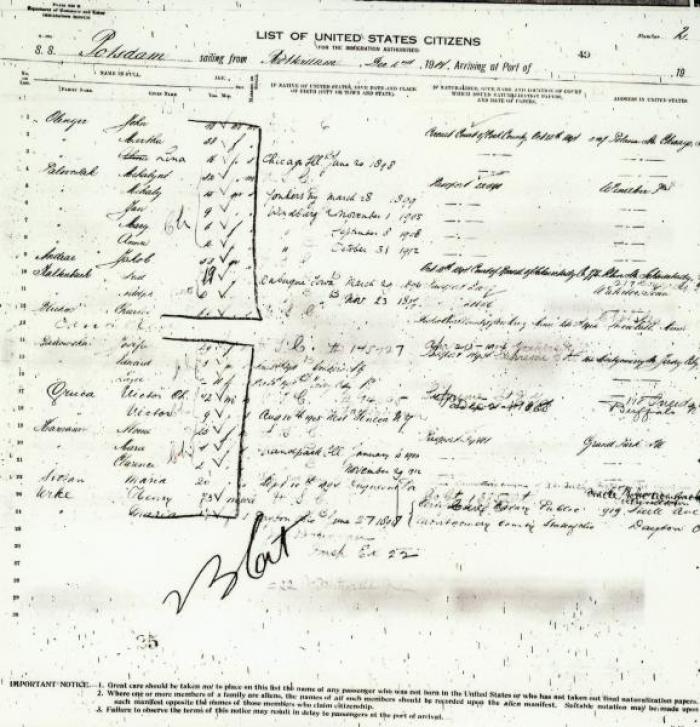

Fred Kaltenbach, through 1927

Fred Kaltenbach, the eldest of the Kaltenbach children, was the first to begin his higher education. He had distinguished himself in debate at Waterloo East High School. His high school principals remembered him as a studious, hard-working young man. But before he started college, Fred and his brother Adolf had an extraordinary adventure. After graduating from high school in 1914, Fred and his slightly younger brother Adolf, later called Gustave or Gus, sailed for a bicycle tour of Germany. Their father financed the trip as a graduation present for Fred, who had shown a serious interest in his parents' homeland. Apparently the family planned the trip well in advance. Fred secured his passport already on January 26, 1914. The boys likely intended to visit relatives and do some sightseeing. However, in August 1914, while Fred and Gustave were in Germany, World War I broke out. German authorities arrested the two brothers as spies, a charge which, in retrospect, seems completely groundless. Fred and Gustave were almost certainly just boys on a bicycle tour. Their family back in Waterloo worked hard to secure the boys' release, but the effort took time. The boys were held until December 1914, when German authorities finally let them go.

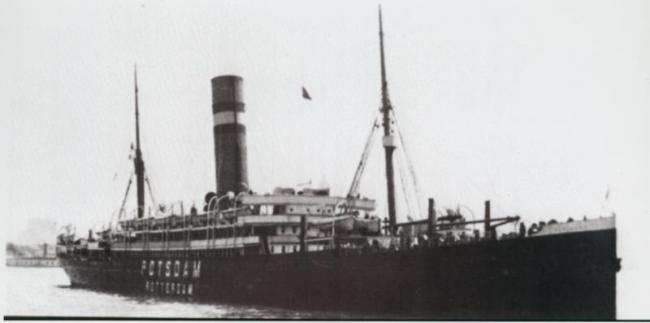

They were allowed to board the Potsdam in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in early December. They arrived in New York on December 15, 1914, and probably took a train back to the Midwest. They must have had some interesting stories to tell when they got back to Waterloo.

That kind of harrowing experience in a foreign country would sour most people's enthusiasm for that country, its history, its government, and its culture. However, in later years Fred Kaltenbach would say that the trip heightened his interest in and respect for Germany. He later wrote: "I was swept by a powerful emotion and something inside me said I am going home."

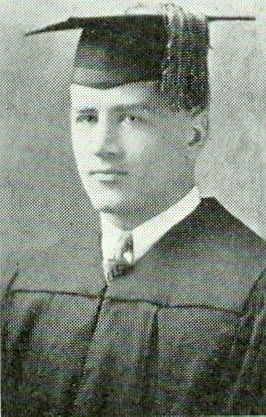

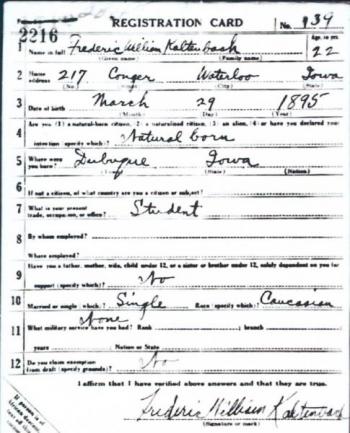

Fred Kaltenbach entered Grinnell College, in Grinnell, Iowa, in the fall of 1915. Grinnell College was a private college. Its $100 annual tuition (about $1375 in 2014 buying power) must have been a substantial sum for the Kaltenbach family. Probably with money that he himself earned, and perhaps with help from his family, Fred was able to pay his bills at Grinnell. In his three years of study there, he distinguished himself in debate and oratory. In that era, achievement in those extracurricular fields brought recognition that was at least comparable, if not superior, to the acclaim given to athletes. But with the United States entering World War I in April 1917, Fred Kaltenbach left Grinnell in the spring of 1917 after completing his junior year. He registered for the draft in Waterloo on May 26, 1917.

Frederick Kaltenbach's draft registration card, May 26, 1917.

He then enlisted in the United States Army on June 10, 1918, in Waterloo, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Coastal Artillery. Given the nature of his military assignment, and with the war ending just a few months later on November 11, 1918, Fred Kaltenbach did not see overseas duty. It is interesting to speculate how his later perspective might have changed if he had had the opportunity to witness actual battle with its terrifying and grim results. The reality of war might have been a powerful antidote to his later romantic, intellectualized point of view on conflict between nations.

Fred Kaltenbach took his Officer Training course at Ft. Monroe, Virginia. He remained in military service for nine and a half months until he was honorably discharged in April 1919. After his discharge, he joined the American Legion and the US Army reserves. He likely then went home and worked during the spring and summer of 1919. But instead of resuming his work at Grinnell College, he enrolled in the Iowa State Teachers College for the fall 1919 term. It is not clear why he made that choice. At that time, the Teachers College curriculum was limited solely to teacher preparation. It did not offer the kind of liberal arts degree for which he had been studying at Grinnell. Perhaps he decided that teaching would be a good career for him. There may also have been family dynamics involved. His sister Elsie had attended the Teachers College in the 1918-1919 school year and would return for the 1919-1920 year. Perhaps she brought home good reports of the school and its work. Or perhaps it was simply a financial decision. Tuition at the Teachers College was just $5 per term. With two children in college and another two headed in that direction in the next several years, finances might have been a critical factor.

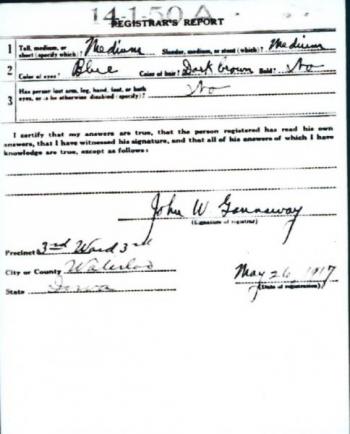

Fred Kaltenbach entered the Teachers College on September 10, 1919. He was twenty-four years old. He was excused from physical training because of his military service. There were no men's dormitories at that time, so he likely lived in Bachelor Hall, an off campus rooming house. Daily commuting to his home on the other side of Waterloo would have been tedious, time-consuming, and expensive. Mr. Kaltenbach hit the ground running at his new school. In October 1919 he took third place in the school's fall oratorical contest and won a $10 prize. In the November declamatory contest, he spoke on William Pitt's "Affairs of America". He took first place in that contest and won a $25 prize. If Mr. Kaltenbach's decision to attend the Teachers College had a financial basis, these two prizes alone certainly helped him. He had also been selected as a member of the Philomathean Literary Society, probably the most prestigious of the men's societies. At the society's Armistice Day program on November 10, 1919, he spoke on "Interference in Russia". He believed that the United States should keep out of the Bolshevik revolution and its aftermath. That attitude reflected the opinions of many Americans, who, at that point, had had enough of war in Europe. Professor Bertha Martin, and almost certainly, Professor Lenore Shanewise, assisted contestants in these contests. The lives of Professor Shanewise and Fred Kaltenbach, both from Waterloo, showed remarkable parallels and coincidences that this writer explores briefly outside of this essay.

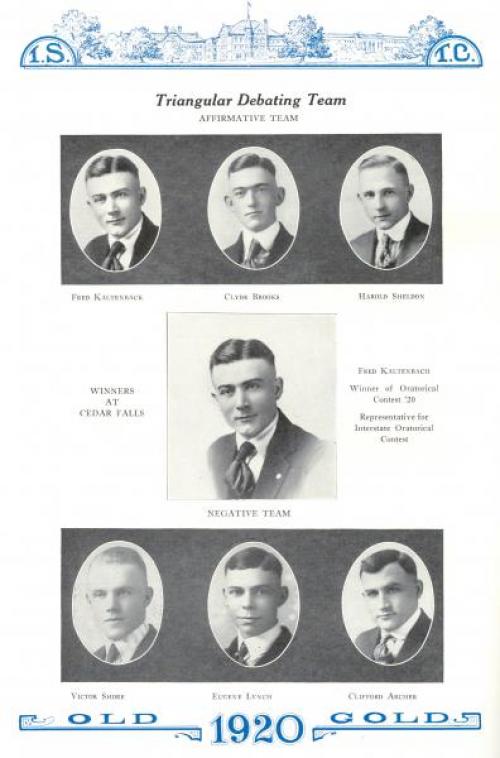

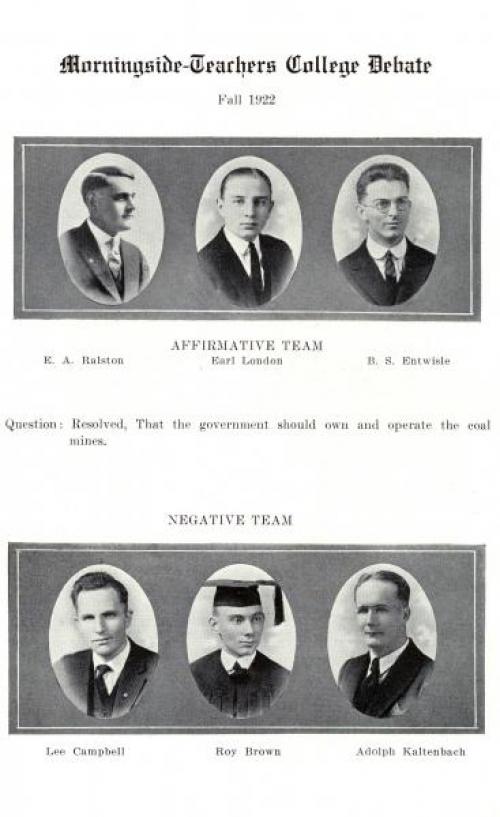

On February 2, 1920, Mr. Kaltenbach won another school oratorical contest, where he spoke on "The Church of Tomorrow". He won the Mead trophy for his literary society and also earned the right to represent the Teachers College at the Interstate Oratorical Contest in Wisconsin in May. Unfortunately, at that contest, representatives from other schools took the prizes. Later in February, and on a decidedly lighter note, he was elected to the newly-reorganized school Pep Club. In that same month he was selected to present the first affirmative position for the school debate team. The question that year centered on railroad regulation. The affirmative team, consisting of Fred Kaltenbach, Clyde Brooks, and Harold Sheldon, defeated Simpson College in March. He and his colleagues received medals from President Seerley at a chapel service. To top off Mr. Kaltenbach's extraordinary work at that time, he was elected president of the Philomathean Literary Society.

In early May, Mr. Kaltenbach presented a short speech on behalf of the senior class at a reception for the faculty and other Teachers College classes. He spoke at an alumni gathering and also at a traditional planting of ivy in late May. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Education degree on August 20, 1920, with a major in government and a minor in history. In his year at the Teachers College, Fred Kaltenbach made an excellent name for himself.

Mr. Kaltenbach did not immediately take a teaching position. This was slightly unusual, but certainly not exceptional. While the sole purpose of the Teachers College was the preparation of teachers, many of its graduates went on to careers in other fields, such as business, law, medicine, social service, and agriculture. Mr. Kaltenbach took a job as an appraiser at the Leavitt & Johnson Trust Company, located at 527 Commercial, Waterloo, Iowa.

The firm specialized in farm mortgages and finances. Due to the depression in the Iowa farm economy after World War I, the mortgage business was likely brisk for companies such as Leavitt & Johnson. Fred Kaltenbach worked there and lived at home on Conger Street for the next seven years. During those years with the Waterloo trust company, he lived quietly. His only known civic involvement was helping to found the Waterloo Young Men's Christian Association. He served as that organization's first president in 1923. He also occasionally went to the Teachers College campus for special events or to visit his siblings Gustave and Erwin, who were enrolled there.

Elsie A. Kaltenbach

Elsie Kaltenbach enrolled at the Teachers College on September 11, 1918, the year before her brothers Fred and Gustave enrolled. She was almost eighteen years old and had just graduated from Waterloo East High School. Elsie Kaltenbach enrolled in a two year course of study aimed at preparing her to teach at the primary grade level. This was a less rigorous course than the one in which Fred was enrolled. However, her course of study was the path that many Teachers College students of that day followed. Indeed, many students did not persist even to a two year diploma; they often enrolled for a term or two and then went out to teach. College credentials were useful, but they were not required for teacher certification. Elsie Kaltenbach was a member of the Eulalian Literary Society. She did not quite finish her two year course in 1920, but she had accumulated sufficient credit to enter the job market successfully.

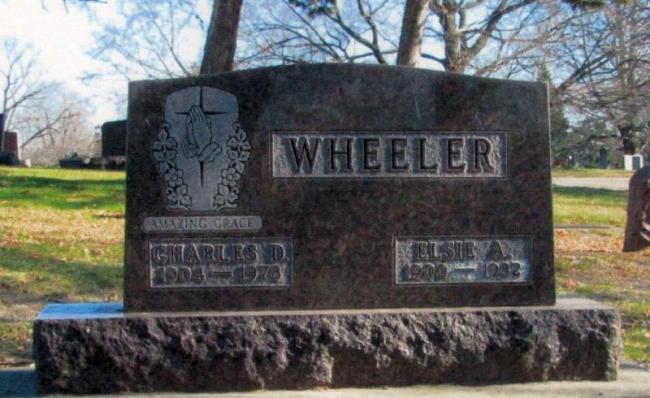

Elsie found a position teaching third and fourth grades in Halfa, Iowa, a small town in Emmet County, but within a year or so she became a teacher at Grant School in Waterloo. She returned to live on Conger Street with her family. She continued in that position through at least 1925 and completed her study through extension work. She received her diploma on June 1, 1926. On August 28, 1926, she married Charles Wheeler. She and her husband raised a family of three children. By 1942, and probably before that date, they lived east of Waterloo. Mr. Wheeler died in 1978 and Mrs. Wheeler died in 1982. They are buried in Fairview Cemetery in Waterloo.

Adolf Gustave Kaltenbach

The next member of the Kaltenbach family to attend the Teachers College was Adolf Gustave Kaltenbach. References show an inconsistency in the spelling and in the order of his given names. Early appearances of his name show both "Adolph" and "Adolf". Also, early appearances tend to show "Adolf Gustave"; later appearances tend to show those names reversed: "Gustave Adolf", "G. Adolf" or "Gustave A". His nickname seems to have been "Gus". This essay will use the latter forms, "Gustave Adolf", simply for consistency. In any case, Gustave was Fred's next younger brother, just a year and a half younger than Fred. As noted above, Gustave had accompanied Fred on the bicycle trip to Germany in 1914.

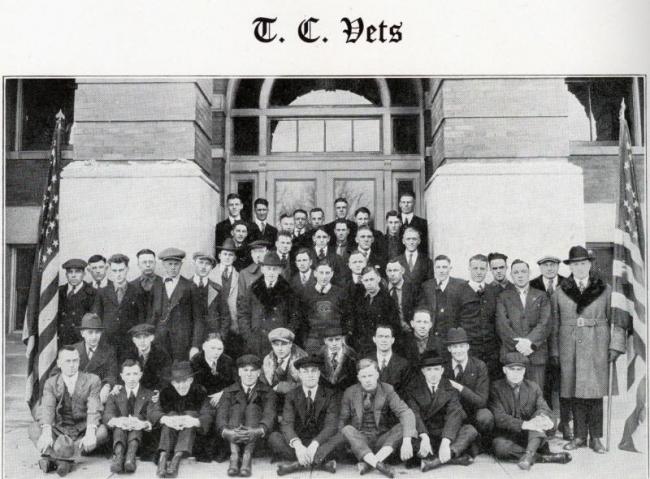

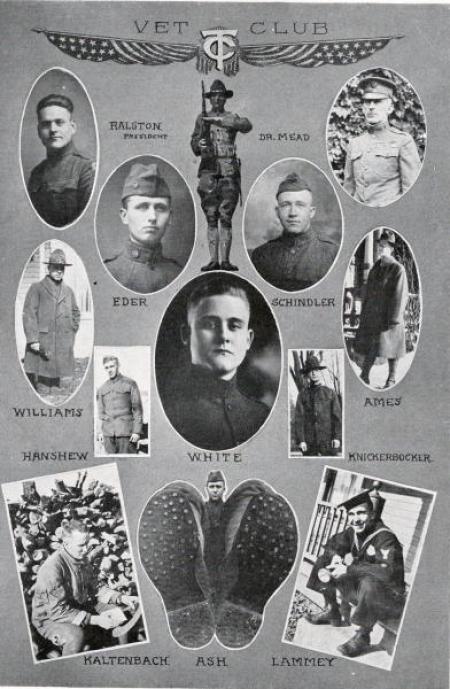

Gustave Kaltenbach served in the American military forces for two years during World War I as a member of the Medical Corps of the US Army's American Expeditionary Force in Europe. He may have joined the US Army before he graduated from high school and then finished high school in 1920, after his discharge. He enrolled at the Teachers College on September 8, 1920. Like his brother Fred, he lived in Bachelor Hall, an off-campus rooming house. Because of his military service, he was excused from physical training classes. In October 1920, he was elected president of the Minnesingers, the best of the men's glee clubs. In November, he was elected to membership in the Philomathean Literary Society, the prestigious society to which Fred had belonged. Also in November, he helped to organize an association of war veterans on campus. He called a meeting of veterans and was elected president of the group.

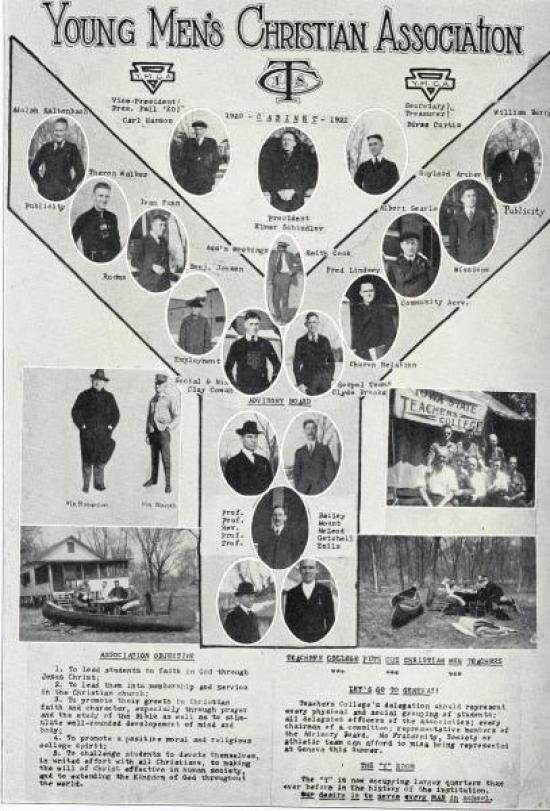

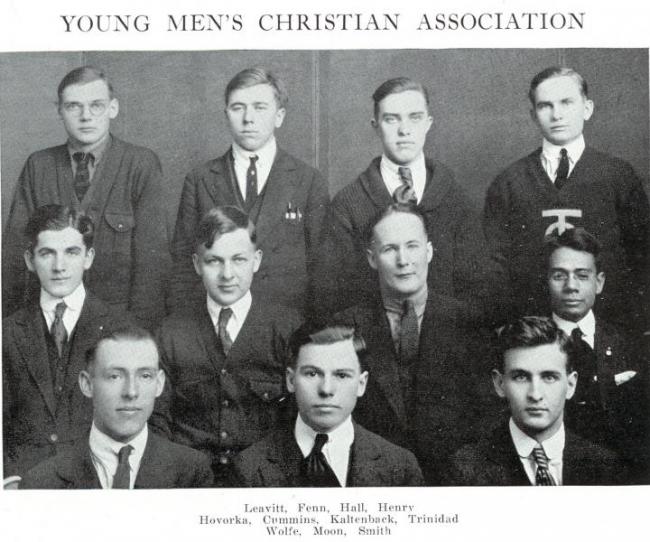

In February 1921 he mounted a campaign to be elected editor-in-chief of the student newspaper, the College Eye, but was unsuccessful in that endeavor. In March he ran for president of the Young Men's Christian Association. This time he was successful by an almost unanimous vote.

At the next Philomathean meeting in April, Gustave gave an amusing set of prophecies for his fellow Philos. A newspaper columnist wrote that the work "showed much preparation and originality."

The 1920-1921 school year had been extraordinary for Gustave Kaltenbach. The next year would prove to be quite similar. In September he attended a state YMCA meeting in Cedar Rapids and brought information back to the campus chapter.

He also was involved in the commemoration of Armistice Day on campus. The perceived lack of respect for Armistice Day in 1919 had been at least one motivation for organizing the TC Vets group. That group had charge of the Armistice commemorative chapel service in 1920. The service went well. There was music, Mr. Kaltenbach read Scripture, student Hans Anderson read a patriotic essay, and the names of alumni who had fallen in the war were read. President Seerley termed it a most impressive experience that culminated with a call for the abolition of war and the installation of peace.

Gustave Kaltenbach then attended a YMCA convention in Chicago in December and spoke with the Hi-Y Club at the campus Training School in February. As his term as president of the campus YMCA drew to a close, he remembered with gratitude the values of the group: contact with other believers, Wednesday evening meetings, morning watch, inspiration, and fellowship. That spring he even tried his hand at drama. He played Antonio in the Commencement production of "Twelfth Night". He also served as president of the Philomatheans for the summer 1922 term.

In the 1922-1923 school year Gustave Kaltenbach again organized the Armistice Day program, but also took up an interest in debating. He was one of five men who received medals for debate work from President Seerley in a January 1923 chapel service.

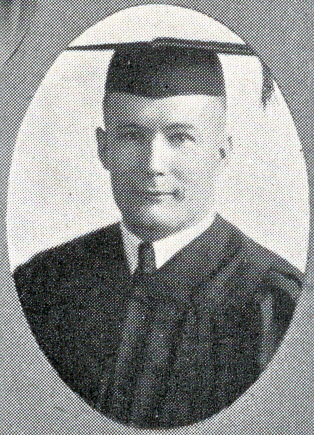

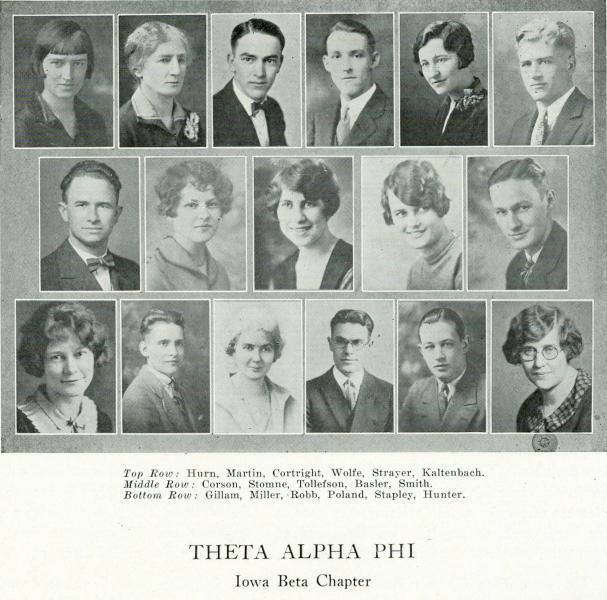

He also became a charter member of the campus chapter of Theta Alpha Phi, the national drama honorary society, in 1923, and was elected president of the senior class for the summer term of 1923. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Education degree on August 23, 1923, with a major in government and a minor in public speaking.

Following graduation, Gustave Kaltenbach married another Teachers College student, Alice Rose Peterson. While in college, he was recognized as an active leader in many areas. But perhaps his most serious and concentrated work had come in the course of his association with the YMCA. He followed that inclination and completed a course of study in theology at McCormick Seminary in Chicago in 1926. This training prepared him for a series of Presbyterian pastorates in Montana, Wisconsin, and Michigan. In September 1942 he enlisted in the US Army and was commissioned as a chaplain. He attained the rank of major. During part of the war, his family lived in Cedar Falls. His children attended the Teachers College and the Training School.

After the war, Gustave Kaltenbach was honorably discharged from the US Army and resumed his civilian Presbyterian pastoral ministry. By 1946 he was serving as a pastor in Hibbing, Minnesota. He continued his service there through at least 1958. At some point after that, possibly when he retired, he moved to southern California. He died there on April 21, 1971. His last residence was Pasadena. His wife, Alice Rose Kaltenbach, died July 23, 1979. They were both buried in Fairview Cemetery, Waterloo, Iowa. Gustave Kaltenbach's grave commemorates his military service.

Erwin John Kaltenbach

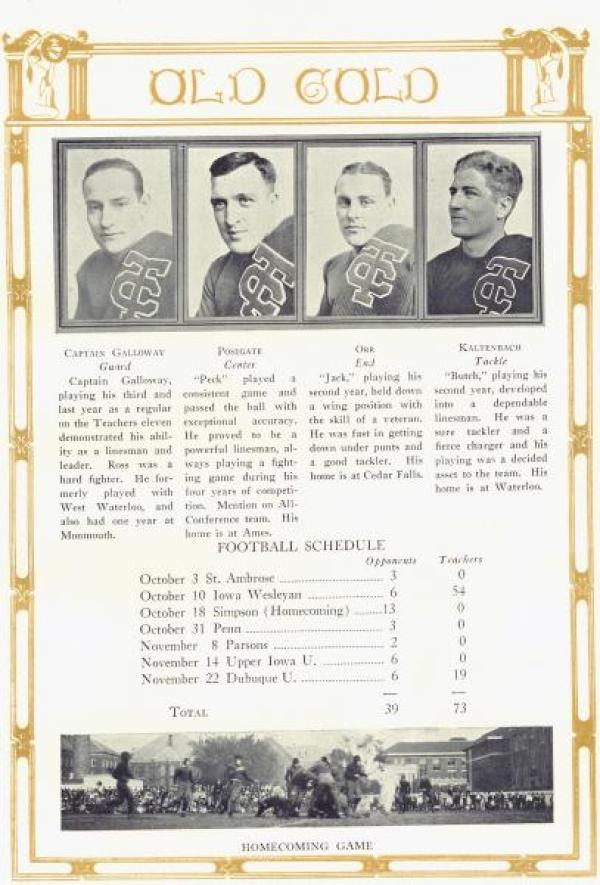

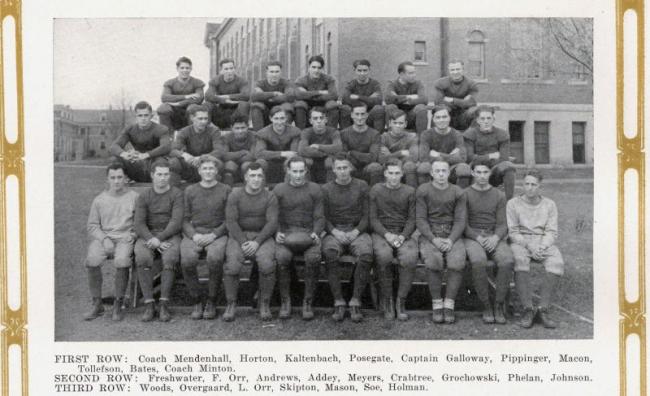

Erwin John Kaltenbach was the next member of the family to attend the Teachers College. He was known by the nickname "Butch". He enrolled in school on September 12, 1923. In some ways he followed in his brothers' footsteps; in other ways he charted a course of his own. Like both of his elder brothers, he had religious values. So, in March 1924, he ran for vice-president of the campus Young Men's Christian Association, but he was defeated by Paul R. Brown. Even though he lost the election, he remained an active participant in the organization's Student Friendship Council. In his freshman year, he became a charter member of the newly-founded Lambda Gamma Nu social fraternity, which had just moved into a house at 24th and Olive Streets.

He also joined the Troubadours, a men's glee club, in which he sang as a first tenor. In the following year, he moved up to the stronger men's glee club, the Minnesingers, and was also elected treasurer of his class.

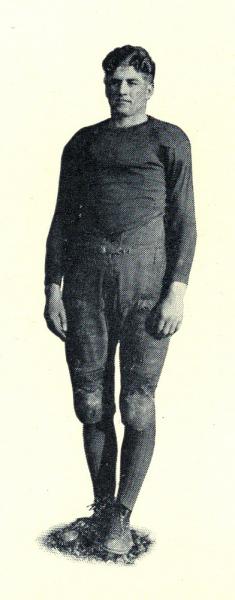

But Erwin Kaltenbach seemed to have strong interests and abilities in athletics, especially football. He was part of a newly-recruited group of Teachers College students. Since the beginning of the school in 1876, women comprised the overwhelming majority of enrolled students. Teaching tended to be a woman's profession. After World War I, President Seerley perceived the need to increase the number of male teachers. His strategy was to draw men to the school by strengthening the curriculm of men's physical education and to develop a coaching emphasis. The strategy was successful. Many men enrolled in physical education courses and participated in athletics with the specific objective of securing a teaching position with coaching responsibilities. Erwin Kaltenbach responded well to this new collegiate emphasis.

Already after his freshman season, Erwin Kaltenbach was heralded as a great addition to the football team.

He lettered in football in the 1923 season. He was interested, but not quite as skilled in other sports, too. In the winter of 1924-1925 he made a little extra money by officiating out-of-town high school basketball games.

His extracurricular work was well-rounded. He served as president of his class for the winter term. In February 1925, as the chairman of the YMCA Gospel Team, he and the team carried the Gospel to Hudson, Iowa, and delivered their message to appreciative audiences. He also played a small role in the 1925 Commencement play, "Pharaoh's Daughter". At the Minnesingers spring banquet, he gave a humorous presentation of "The Old Gray Mare She Ain't What She Used to Be"--in German!

Coach Paul Bender did not believe that the prospects for the 1925 football season looked bright, though he specifically looked forward to the return of Erwin Kaltenbach on the line. For several reasons, fielding good athletics teams was always a challenge at the Teachers College. First, there were comparatively few men enrolled. And, second, the men who did enroll often did not persist to a three or four year degree. They often enrolled for a few terms and then left school to teach. In this case, Coach Bender's pessimistic outlook did not pan out. The team finished with a strong 5-1-2 record. Erwin Kaltenbach won another football letter. The Old Gold yearbook praised him as:

"'Butch", the fighting Teuton, playing his third year at a tackle position. A scrapper from start to finish. "Butch" will be back in the harness next year."

Erwin Kaltenbach did not play intercollegiate basketball, but he was named to the first team intramural basketball squad in the winter of 1925-1926.

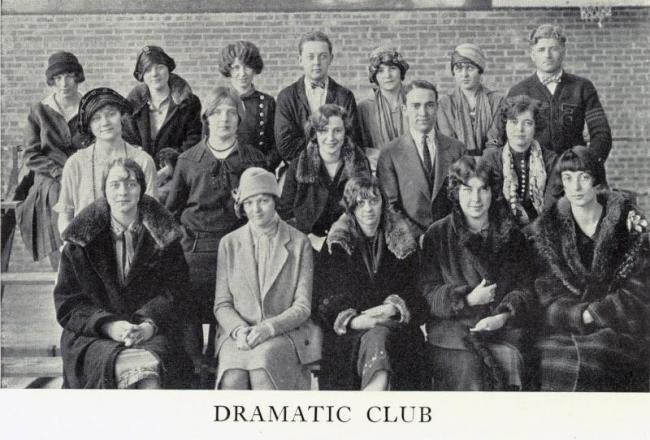

As usual, Erwin Kaltenbach also kept involved with the Minnesingers and the Dramatic Club. He was initiated into Theta Alpha Phi, the national drama honorary society, of which his brother Gustave had been a charter member.

In his senior year, Erwin Kaltenbach was elected president of his class for the fall term. During the football season, he suffered a severe knee injury in an early game. The injury limited his play to the extent that he did not qualify for a letter or for the blanket that was awarded to four-year letterwinners.

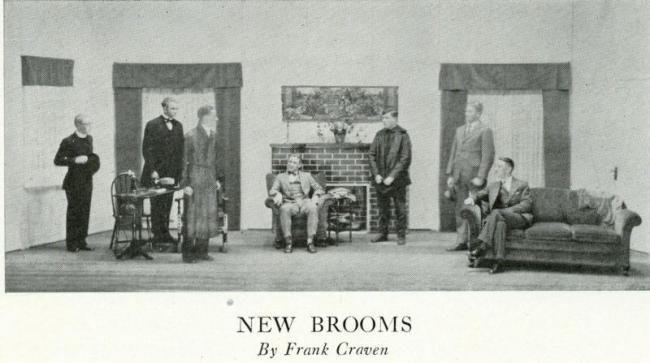

But he did play a small role in the mid-winter play, "New Brooms", and he assisted with the Senior Prom.

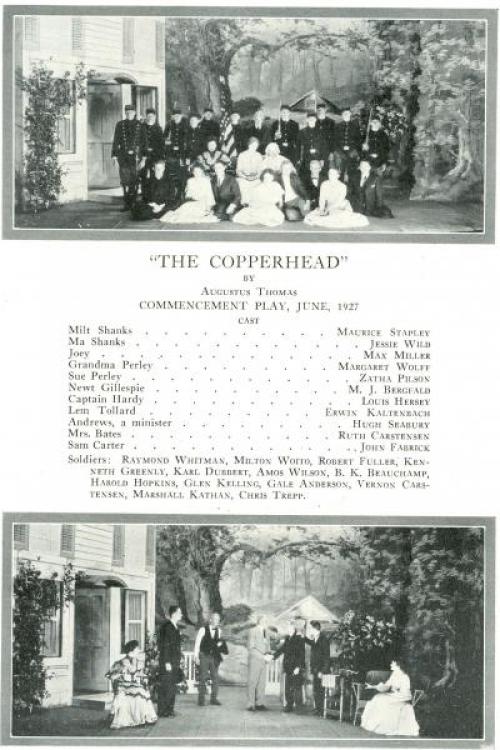

He recovered enough from his injury to be named to the intramural basketball all-star team again. As part of the Commencement activities, he again played a small role in the dramatic production, "The Copperhead". The play was so well received that it was produced again for summer school students.

Erwin Kaltenbach graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Education degree on May 31,1927, with a major in government and a minor in public speaking. He had put together a nicely rounded college career that would prove attractive to school boards.

The school board at Clermont, Iowa, hired him as principal, coach, and social science instructor for the 1927-1928 school year. Teachers College officials cited him and others as models of the curricular change that produced men with strong academic and coaching credentials. Such men were in demand by many Iowa high schools.

On July 20, 1929, Erwin Kaltenbach married Clarice Johnson of Lime Springs, Iowa. Clarice Johnson was born December 4, 1905, in Chester, Iowa. She was the daughter of John and Francis Smith Johnson. Erwin Kaltenbach's elder brother Fred witnessed the marriage ceremony. At that time Erwin Kaltenbach was superintendent of schools in Clermont. Mr. and Mrs. Erwin Kaltenbach had at least one child. In 1932 he returned to the Teachers College for study in the summer term. By 1934 Erwin Kaltenbach was superintendent of schools in Melbourne, Iowa. In 1937 he completed his master's degree at the University of Iowa. By 1939 he had moved on to Ottumwa, Iowa. His 1942 Ottumwa basketball team won the state high school basketball championship, with a 29-1 record. From 1940 through 1942, his basketball teams won sixty-one of its seventy-eight games.

in 1942 he joined the US Army, and served, at least initially, in the infantry. Unlike most servicemen, he did not leave the Army immediately following the war; instead he became a career officer. When he finished his career, which included service in the Korean War, he had attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. During the postwar years he served with American occupation troops in Germany. Records of the American Consulate indicate that he married Theodora Evelyn Anderson, an American woman, on May 7, 1949, in Berlin. It seems likely that Erwin and Clarice Kaltenbach had been divorced. War and overseas duty can be hard on marriage.

Erwin John Kaltenbach, the last surviving Kaltenbach sibling, died January 10, 1992. He was buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, California.

Roy M. Kaltenbach

Roy M. (possibly Max) Kaltenbach, born on December 16, 1906, was the youngest member of the family. Like his brothers and sister, he attended Waterloo schools. However, he does not seem to have attended college. He lived in the Conger Street house and likely helped to take care of his father and mother in their later years. In 1925, the Waterloo city directory mentions Roy Kaltenbach's occupation as a clerk, but the directory does not specify the location or nature of that work. The directories do not list Roy Kaltenbach's occupation again until 1939, when he is reported as a helper at the McStay wholesale meat market in Waterloo. He is then listed as a helper at the Skaags wholesale meat market in 1943. After working for some time as a sweeper at the Galloway Farm Implement Company, Roy Kaltenbach was working at Deere and Company by 1948. His work is variously described as laborer, clean-up man, and janitor. He likely stayed with Deere until he retired in about 1966. He lived in a number of Waterloo locations after leaving Conger Street.

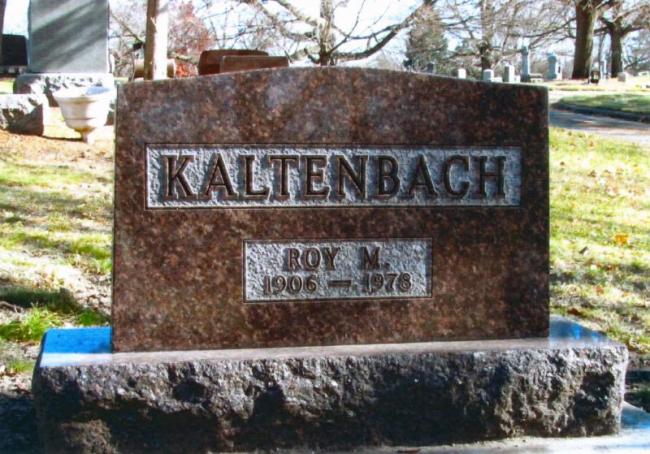

On March 10, 1961, Roy Kaltenbach married Ardith Buenneke, in Fillmore County, Minnesota. She was born in Waterloo in 1918, the daughter of Archie William and Marie E. Aasgaard Kilby. She had three children from a previous marriage. Mr. and Mrs. Roy Kaltenbach lived in several locations in Waterloo until her death in 1970. She was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Waterloo. After his wife's death, Roy Kaltenbach apparently lived alone in several Waterloo locations until his death in 1978. He was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Waterloo, the cemetery in which his parents and his little sister Hilda Marie were buried. His brother Gustave was also buried there and Gustave's wife would be buried there within a year.

Fred Kaltenbach, 1927-1945

In 1927, Fred Kaltenbach secured a position teaching American history in the public schools of Manchester, Iowa, a town about fifty miles east of Waterloo. It is not clear why he left his job with the trust company. Perhaps business slowed. Perhaps he just wished to be a teacher. His work in Manchester was successful enough for him to obtain a better position at the Dubuque High School in 1931.

There he taught business law, history, debate, and economics. In the summers, he studied at the University of Chicago, where he received a master's degree in history. In 1933, he obtained a scholarship from the University of Berlin in order to work on a doctoral degree. He received a two year leave of absence from the Dubuque schools and sailed to Germany.

Living and studying in Germany for the next two years was probably a tipping point for Fred Kaltenbach. When he and his brother had been in Germany in 1914, that country was a strong, thriving, imperial world power. But since that time, Germany had suffered defeat in war; loss of domestic and overseas territory; financial ruin due to reparation payments and global depression; hyperinflation; and weak and shifting government. Civic morale was low. However, Adolf Hitler had taken power on January 30, 1933. By any means available--legal and illegal--he sought to restore the nation's power and to eradicate the spirit of defeatism among its people. At least for a time, many Germans believed that their new Chancellor would lead their nation back to what they believed to be its rightful place in the world. Hitler cast blame widely. He began to ignore limits placed on Germany under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. He used terror to stifle dissent. After years of suffering, many Germans were excited by their prospects.

This was the heady, emotional atmosphere in which Fred Kaltenbach found himself in Berlin in 1933. Already strongly pro-German, he seemed to embrace everything German--even the obvious excesses of Nazism--without question. It is not now clear exactly what facet of history he was studying from 1933 through 1935. After two years, he returned to his teaching position in Dubuque. But he was a changed man. Shortly after he returned to Dubuque, he organized a youth group that quite clearly resembled the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) that he had observed in Germany. Members of his Militant Order of the Spartan Knights wore brown shirts, held secret meetings, and carried stout sticks on their hikes and outings. One person claimed, perhaps without basis, that Mr. Kaltenbach even requested that the members be allowed to carry rifles. Parents and townspeople were quick to make the connection to what was occurring in Germany. The local American Legion called Mr. Kaltenbach to appear at a meeting, but quiet discussion was not the order of the day. The meeting turned into a confrontation, perhaps with threats and violence involved. School officials put an end to the youth group and did not renew Mr. Kaltenbach's contract for the next year.

Fred Kaltenbach returned to Germany, where he apparently earned at least some money as a translator and as an employee of the Ministry of Propaganda. He probably resumed his formal studies at the University of Berlin and received a doctorate. He conducted research on what he considered to be the destructive effects of the Treaty of Versailles on Germany. In the late 1930s, this was scarcely a novel thesis. Indeed, shortly after the treaty was signed in 1919, it was clear that the punishment inflicted on Germany by the Allies--justifiable or not--would have grave long-term consequences for all parties involved.

The initial plan of the Allies was to strip Germany of money, military strength, and territory. The Allies intended to keep Germany weak and unable to start another war for a very long time. Instead, the treaty provisions provoked a political movement that produced German National Socialism in just a few years. Mr. Kaltenbach's research resulted in a 1938 book entitled Self Determination 1919: a study in frontier-making between Germany and Poland. In a respected scholarly journal, The Slavonic and East European Review, reviewer W. J. Rose stated that Mr. Kaltenbach's book had at least some value in drawing attention to an important question. However, Mr. Rose strongly criticized the unscientific and incorrect views upon which Mr. Kaltenbach based his work. He also found that Mr. Kaltenbach inexplicably ignored key bibliographic resources relevant to the subject.

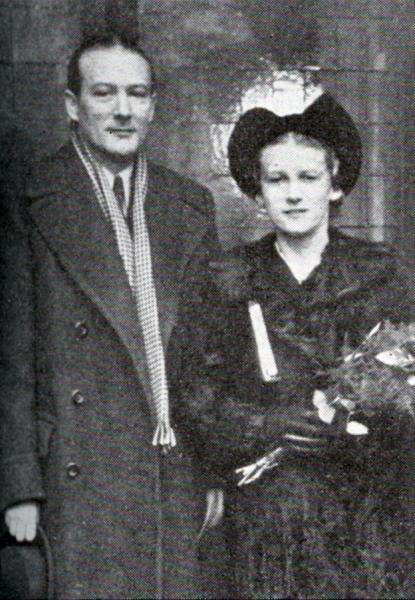

In February 1939, Fred Kaltenbach married a German woman, Dorothea Peters, who worked for an aviation magazine published under the auspices of Luftwaffe commander Herman Göring. In retrospect, it is interesting to speculate how Fred Kaltenbach and Dorothea Peters met or even if the meeting and marriage might have been fostered by Nazi officials. The marriage might have been a way to cement Mr. Kaltenbach's loyalties even more firmly to Germany and its Nazi government.

Shortly after the marriage, Mr. Kaltenbach became a broadcaster on the German shortwave radio network that delivered propaganda to the United States. The government also sent him and his new wife to America for a visit, which was planned to last the entire summer of 1939. Over the course of a few weeks, Mr. Kaltenbach visited all of his close family. First, he visited his brother Gustave in Ironwood, Michigan, where Gustave served as pastor of the Presbyterian church. Fred spoke on the Nazi point of view to his brother's congregation. Fred then visited his brother Erwin in Ottumwa, Iowa, where Erwin taught and coached in the Ottumwa schools. Fred again spoke about the superiority of the German political position. He even spoke to student groups at the University of Iowa.

Fred Kaltenbach's last stop turned out to be his hometown, Waterloo. Some of that visit was social and family-oriented. He visited his father, John Kaltenbach, who was very ill, and would die just a few weeks later on May 20, 1939. Fred Kaltenbach also visited his brother Roy and his sister Elsie, who both lived in the Waterloo area. He even visited the Teachers College campus, where he met with Albert C. Fuller, Director of Alumni Affairs.

Professor Fuller reported later that Mr. Kaltenbach considered Nazism to be a religion. Fred Kaltenbach made public presentations in the Waterloo area, as well. On May 1, he addressed the Waterloo Rotary Club at the Russell Lamson Hotel. (In an interesting sidelight, Russell Lamson, Jr., a member of the family for whom the hotel was named, had been Fred Kaltenbach's acquaintance and classmate at the Teachers College). The presentation did not go well; Rotary members reportedly booed his remarks and questioned his loyalties. An article in Time magazine, January 8, 1940, even includes a brief exchange from that meeting. A Rotarian reportedly asked: "If you like Nazi Germany so much, why don't you go back there and stay?" Mr. Kaltenbach replied, "I am." His response was prophetic.

Perhaps he was discouraged by the reception for his lectures during the entire course of his visit to the United States. Perhaps the German masters who controlled his purse strings believed him to be ineffective. Perhaps Nazi officials wanted him home early to help prepare propaganda for their invasion of Poland in September. For whatever reason or complex of reasons, and even with his father nearing death, Fred Kaltenbach and his new wife ended their American trip shortly after their stop in Waterloo and returned to Germany.

After the war began in September 1939, Fred Kaltenbach became an increasingly important part of the German overseas radio propaganda effort. He was in many ways ideally suited for the job. He was well-educated and well-spoken. He knew both German and English at the level of a native speaker. He apparently was witty and had a pleasant personality. He was trained, experienced, and respected in both oratory and debate. And, to the benefit of the German point of view, he was a true believer in the Nazi philosophy.

For the first several years of his broadcasts, before the United States entered the war, Fred Kaltenbach, in tune with Nazi government strategy, attempted to sow discord in America by stirring up jealousies, rivalries, and prejudices. He urged Americans not to re-elect President Franklin Roosevelt, who was a strong supporter of Great Britain. And he tried to persuade Americans to maintain their isolationist stance and stay out of the European war. His work was not the hysterical shouting that often characterized Nazi oratory. Rather, his programs, initially entitled "Letters to Iowa", took a folksy, homespun approach. In the form of fictional letters, he addressed his remarks and advice to "my old friend, Harry, in Iowa". "Harry" seems to have been a fictionalization of an old school friend, Harry Hagemann. Mr. Hagemann had become a successful attorney in Waverly, Iowa, and was later named to the Iowa Board of Regents. Hagemann Hall, a residence hall on the University of Northern Iowa campus, is named in his honor. Mr. Hagemann, of course, had no idea what Fred Kaltenbach was doing. Nor did he have any sympathy with Fred Kaltenbach's views.

The Nazi propaganda masters apparently believed that Fred Kaltenbach was doing a good job. They created new programming for him so that his broadcasts to the United States could be heard four times per week. During this time Fred Kaltenbach also acquired an on-the-air nickname. William Joyce, who broadcast Nazi-themed programming to Great Britain, had come to be known as Lord Haw-Haw. Fred Kaltenbach, with reference to Iowa agricultural roots, became known as Lord Hee-Haw. Even though his Nazi masters seemed to like Fred Kaltenbach's work, he did not achieve tangible results in the time leading up to direct American participation in the war in December 1941. President Roosevelt was re-elected. American society moved along without much change. And, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans united strongly in their efforts to assist the British and other allies and to defeat the Axis powers.

When the United States officially declared war on Germany on December 11, 1941, Fred Kaltenbach's potential legal situation changed. He was still an American citizen. Before the declaration of war, his broadcasts might have put him into a gray legal area. He had certainly been saying things that were detrimental to the United States and supportive of Germany, but, if pressed, he might have defended himself by citing his Constitutional right of free speech. After Germany became an official wartime enemy, though, Fred Kaltenbach was skirting dangerously close to a charge of treason, a capital crime. Even so, legal matters proceeded slowly. It was not until July 26, 1943, that a federal grand jury in Washington, D. C., indicted Fred Kaltenbach and eight others for treason. He seemed surprised by the charge and attempted to defend himself with the usual rationale of those who find themselves in similar positions: he said that he was against American leaders and war profiteers, but he was standing up for the American people.

Probably from the shock of the indictment and in the turn of the tides of war, Fred Kaltenbach's broadcasts declined in quantity and quality. War was no longer an intellectual exercise accompanied by witty asides and humorous stories. It was an endgame for all concerned. His claims of Nazi military and philosophical superiority flew in the face of what just about everyone saw, knew, and believed. He apparently grew moody and argumentative with Nazi leadership. He occasionally refused to honor his broadcast commitments. He also became ill with heart problems and asthma. But as late as 1945 he still could be heard now and then on the Nazi shortwave network in Europe and in the United States.

When Berlin fell to Allied forces in late April 1945, Fred Kaltenbach and his wife stayed in their five room apartment. With an indictment for treason hanging over him, they must have known that American forces would be looking for him. It must have been a frightening time. However, just as the Americans were about to take him into custody, Soviet officials located him and arrested him. That began a period of uncertainty for everyone who was concerned about Fred Kaltenbach's fate. The Americans requested information about him from the Soviets. The Soviets initially denied that they had him in custody. Matters dragged on for over a year. The Americans heard from Mr. Kaltenbach's fellow prisoners that Fred Kaltenbach had indeed been in Soviet hands. The Soviets then admitted that they had him and that they would turn him over to the Americans. But when the time for his release came and then passed, the Soviets finally stated that Fred Kaltenbach had died of "natural causes" in Soviet custody in October 1945. The site of his death and burial was unknown. Neither his wife nor the United States government took the Soviets at their word. They persisted in their attempts either to find Mr. Kaltenbach or to get more concrete evidence of his death. However, nothing more was forthcoming. The United States ultimately dismissed the indictment against him on April 13, 1948. In all likelihood, the Soviet story held a grain of truth. Chaos prevailed in Berlin in the immediate aftermath of the war. Both the Soviets and the Allies had long lists of "persons of interest". The Soviets happened to find Fred Kaltenbach first. Prison camp life would have been very tough for him. And he had been quite ill. Perhaps, under those conditions, Fred Kaltenbach really had died of natural causes after a few months in Soviet custody.

It is interesting to speculate what might have happened to Fred Kaltenbach had he fallen into American hands and been returned to the United States. Had his case gone to court, agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other security agencies had mountains of evidence in the form of recordings and transcripts of his broadcasts. Anyone interested in the content of the Kaltenbach broadcasts should read the article by Clayton D. Laurie, "Goebbel's Iowan: Frederick W. Kaltenbach and Nazi short-wave radio broadcasts to America, 1939-1945", Annals of Iowa, Summer 1994, pages 219-245. Professor Laurie's in-depth research in government files gives an extraordinarily good account of both the tenor of the broadcasts and the government case against Mr. Kaltenbach. According to Professor Laurie, Fred Kaltenbach was known at the highest level of government: President Roosevelt and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover knew his name. The government would also likely have produced witnesses to Mr. Kaltenbach's actions and remarks over the course of his years in Germany. Such testimony might have been hard to refute. In addition, the defense and the government might have produced character witnesses, even though such witnesses can seldom actually settle matters. In just about any case, there will be people who will say, in all honesty, that the accused person had always been a hard-working, intelligent, thoughtful, and loyal American. And then there will be others, again with all honesty, who will say that they always knew that the accused would come to a bad end. The writer of this essay had the opportunity to see only brief excerpts from Fred Kaltenbach's broadcasts. Those excepts, likely selected to show treasonous potential, seemed tame, sometimes even innocuous. One can hear much stronger statements expressed regularly on today's radio and television political talk shows. But, again, Fred Kaltenbach expressed his views when the United States was at war.

Some of Fred Kaltenbach's media contemporaries thought that he was merely a puppet of the Ministry of Propaganda. They would claim that while many Americans listened to Mr. Kaltenbach on the radio, it is very unlikely that he changed anyone's mind, drove people to sabotage, caused men to avoid the draft, or seriously disrupted civic morale. Mr. Kaltenbach's brief tour of the Midwest in 1939 showed that Americans did not fall for his baseless claims, racial theories, or arguments that ran counter to their own values, experience, knowledge, and common sense. And that was over two years before the United States entered the war. If anything, American attitudes hardened against Nazism as time went on. Still, ineffectiveness as a propagandist is not a strong defense against treason.

Noted historian and foreign correspondent William L. Shirer, author of the landmark The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, thought that Fred Kaltenbach was among the strongest of the Nazi radio propagandists. Mr. Shirer thought that Fred Kaltenbach's strength as a broadcaster was derived from his firm belief in the efficacy of Nazi philosophy. Had Mr. Kaltenbach's trial taken place shortly after the war ended, he might have faced severe punishment. His shortwave radio colleague, the vitriolic William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw), was quickly sentenced to death in 1945.

Had it taken several years to bring the case to trial, attitudes might have been more forgiving. In 1949, Iva Toguri D'Quino, known popularly as Tokyo Rose, received a prison sentence of ten years for her propaganda broadcasts. Her softer broadcast tone and style were similar to those of Fred Kaltenbach.

The news of Fred Kaltenbach's capture by the Soviets and then his death was distressing to his family in the United States. Knowing that one's brother was in a Soviet prison camp and was then buried in an unknown grave must have been difficult. His sister and brothers had no sympathy for the opinions which Fred Kaltenbach expressed during his years in Germany. They had not even heard from him since 1941. But he was still their brother. Whenever bits of news about Fred Kaltenbach trickled out shortly after the war, reporters would call his sister and brothers for comments. Those calls, probably made by reporters in hopes of a sensational story, must have been troubling for the family. Similar calls continued to some extent even years later. Occasionally, one of the siblings offered some slight response. In most cases they chose not to take part in the reporter's game and wisely gave no comment.

Summary and Conclusion

So, what went wrong? Why did four of the Kaltenbach children lead solid, productive American lives, while one went in a bad direction? At this point, no one can answer that question definitively. But the question does invite speculation. If the Kaltenbachs were similar to many immigrant families, of any ethnic origin, the older children likely spent their early years in a more ethnic atmosphere. Both parents, John and Anna Kaltenbach, had come to America as adults. They spent their formative years as German citizens. They understood and accepted German history, values, and culture. In addition, the children's maternal grandmother, Salome Scheppele, lived with the family until at least 1900, and possibly a bit beyond that date. Almost certainly, the family spoke German at home in the early years. But, as members of the family moved out into the community for work or school, things likely began to change. John and Anna Kaltenbach, in the course of their employment, must have learned at least some English and must also have become better acquainted with American values and practices. Likewise, when the older children entered public school, they brought the English language and American values home to their parents and their younger siblings. Older children in ethnic families often know their parents' native language very well; younger children sometimes know only a few words and expressions in that language. It cannot now be proven, but perhaps Fred Kaltenbach was raised in a home atmosphere that was more German, and less American, than it was when his brothers and sisters came along. There is no fault to be found in that situation. When people emigrate to a new country, they do not take on a new nationality overnight. Acculturation needs to grow.

There is no reason to think that some particular thing about the Kaltenbach household turned Fred Kaltenbach into a Nazi propagandist. If that were so, then why did the rest of his siblings show not even an outward hint of similar inclinations in their lives? Gustave Kaltenbach, just a year and a half younger than Fred, accompanied Fred on the bicycle trip to Germany in 1914. Despite difficult circumstances in Germany, Fred came home flushed with emotion and love for that country. Gustave moved on in ordinary American directions. Fred Kaltenbach's siblings gained strength from their upbring to become solid Americans. Fred gained strength there, too, but circumstances seemed to overcome those strengths.

Fred Kaltenbach got off to a solid start on a productive American life. He did well in school, served in the US Army, and found steady employment. He lived at home and helped to take care of his parents until he found teaching positions away from Waterloo. He participated in and led YMCA activities. As noted above, the Kaltenbach siblings tended to marry late. His brother Gustave was past thirty when he married. Elsie was almost twenty-six. Erwin was almost twenty-five. Fred was almost forty-four. Roy did not marry until he was 54. Gustave, Elsie, and Erwin had the distractions and responsibilities of caring for their own families long before Fred married. And Roy, who did not marry until quite late, likely had a physically demanding job as well as responsibilities for his parents. Familial responsibilities have a way of both focusing and expanding a person's outlook. Day-to-day care and consideration for a spouse, children, or aged parents provide focus. Seeing new things from the points of view of other members of the family provides an expanded vision of life. Fred Kaltenbach did not have these distractions, or opportunities, until much later in life. He seemed to have a studious, serious frame of mind. His strength in debate and oratory showed that he was not shy about expressing himself in groups. He seemed to have a romantic, old-fashioned, philosophical perception of Germany that even his own personal experience and observations could not shake. Being arrested as a spy in Germany in 1914 could not shake it. Nor could World War I military service on behalf of the United States and against Germany upset his vision. Unlike his siblings, Fred Kaltenbach might have had too many years to strengthen his old ideas and not enough stimulus or opportunity to develop new ideas that were more in tune with the wider world around him.

The scholarship to study at the University of Berlin in 1933, that critical year in German history, probably set Fred Kaltenbach on a course from which he could not turn back. Those two years in Germany, with Hitler riding an early wave of popular support, cemented his pro-German outlook. When he resumed his teaching position in Dubuque, he might have considered himself a missionary for that outlook. He likely did not understand why people reacted so strongly to his attempts to create a little Vaterland in eastern Iowa. But they did indeed react to the extent that he lost his teaching job and returned to Germany. The German Ministry of Propaganda considered this well-spoken, educated German-American a prize. The ministry cultivated him. They likely saw to it that he did well at the university, found employment, and lived comfortably. He likely was dazzled by that attention and by his access to key Nazi officials. He gradually became a spokesman not for only the German nation but also for its Nazi government. He was not a prisoner of the Nazis; he was a voluntary spokesman for the government point of view. He had plenty of time to open his eyes to see what was really happening in Germany, but he did not.

Fred Kaltenbach was not a valueless cynic. He had been raised in a Presbyterian family that must have taken its religion seriously. Both his brothers Gustave and Erwin had been significantly involved in YMCA activities at the Teachers College. Gustave had gone on to make a career as a Presbyterian clergyman. Fred himself was a leader in YMCA activities in Waterloo. He even lived at the YMCA while he was teaching in Dubuque. There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of his devotion to his faith or to these activities. But, after his visits to Germany, his family's faith no longer satisfied him. His system of belief had always included room for religious faith. Unfortunately, Nazism moved into that space. Professor Fuller's remark in 1939 that Nazism had become a religion for Fred Kaltenbach was not an exaggeration.

The Kaltenbach family followed the path of most immigrant families in America. They went to school, worked hard, established families of their own, and were assimilated into the general population. Within a generation or two, most of the outward elements of their ethnic identity faded. But Fred Kaltenbach was the exception. Perhaps due to an unfortunate confluence of circumstances, a rigid frame of mind, and a lack of distractions and opportunities for empathy in his life, he focused on bad ideas and values. He paid the price for his choices with death and an unmarked grave in a miserable Soviet prison camp.

Essay by University Archivist Gerald L. Peterson, with scanning by Library Assistant Joy Lynn and research assistance by Registrar staff member Irene Elbert, Reference Librarian Chris Neuhaus, and Student Assistant Mackenzi Brophy, June-July 2014; last updated, July 30, 2014 (GP).